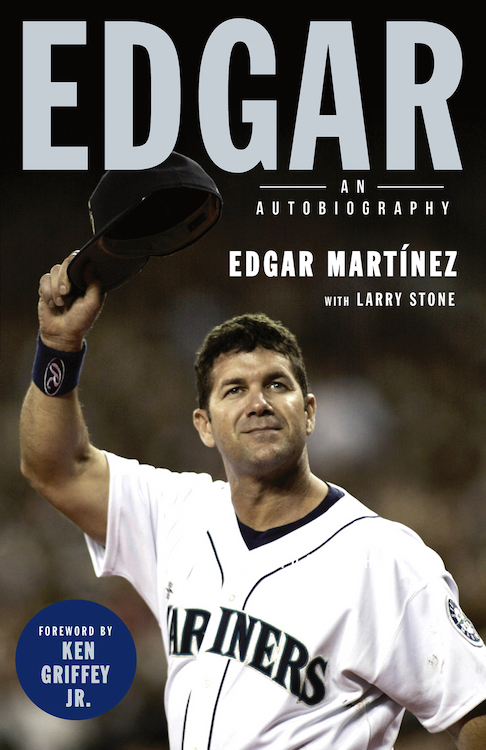

Edgar: An Autobiography is Yet Another Hit for Martinez

Edgar Martinez’s story — at least as recounted in Edgar: An Autobiography, written with veteran Seattle sports scribe Larry Stone and published by Triumph Books earlier this month — reads like something of a fairy tale. Born in New York City in 1963, he moved to Puerto Rico when his parents split, and was raised in the Maguayo neighborhood of Dorado by his maternal grandparents, whom he chose to stay with at age 11, even after his parents reconciled and returned to New York. Though his love for the game was kindled by the heroics of Roberto Clemente in the 1971 World Series, and his development stoked by his relationship with cousin Carmelo Martinez, who spent nine years in the majors (1983-91), he didn’t sign a professional contract until just before his 20th birthday; putting aside $4-an-hour work on an assembly line, he received just a $4,000 bonus from the Mariners. Despite hitting a homerless .173 in his first professional season (1983), and battling an eye condition called strabismus, in which his right eye drifted out of alignment, the Mariners stuck with him.

While Martinez debuted in the majors in 1987, he spent three seasons trying to surmount the Mariners’ internal competition at third base, wound up shuttling back and forth to Triple-A Calgary, and didn’t secure a full-time job until 1990, his age-27 season. Though he won a batting title in 1992, a slew of injuries — shoulder, hamstring, wrist — threatened to derail his career until the Mariners convinced him to become a full-time designated hitter. Once he did, he became one of the AL’s most dominant players; from 1995-2001, he hit .329/.446/.574 for a 162 wRC+ (third in the majors) and 39.9 WAR (seventh, less than one win behind teammate Ken Griffey Jr.).

His heroics not only helped the Mariners reach the playoffs for the first time in 1995 (a year in which he also won his second batting title), but he became a one-man wrecking crew in that year’s Division Series against the Yankees, capping his .571/.667/1.000 performance with a series-winning double in Game 5 that basically saved baseball in Seattle. Remaining with the team for the duration of his career, which lasted through 2004 and included three other postseason appearances, further endeared him to a city that watched Griffey and fellow Mariners Randy Johnson and Alex Rodriguez depart for greener pastures. When he retired, Major League Baseball renamed its annual award for the best designated hitter in his honor. Earlier this year, in his 10th and final cycle of eligibility, he was elected to the Hall of Fame, that after more than tripling his support from just four years earlier.

Martinez’s arc seems so improbable, and yet it’s all true. Over the course of Edgar’s 352 pages, Martinez candidly details the highlights and lowlights of his career, the big decisions, unlikely events, and tactics that helped him surmount so many obstacles. Stone provides testimony from his former managers, coaches, and teammates in the form of sidebars that offer additional perspectives and enhance the narrative.

Having been just about the only person in New York City rooting for the Mariners in the 1995 Division Series, and having promoted Martinez’s Hall of Fame case at Baseball Prospectus, Sports Illustrated, and FanGraphs — as well as in my book, The Cooperstown Casebook — I couldn’t pass up an opportunity to talk to the man about his career and his book. What follows are the highlights of our conversation, edited slightly for clarity.

…

Jay Jaffe: How did this book come about? Obviously, it takes more than just being elected to the Hall and then turning it out in a couple months — I know this having written a book myself, and I know you’re not known for calling attention to yourself.

Edgar Martinez: About five or six years ago, I talked to Larry Stone about writing a paper or something, not necessarily a book, maybe a pamphlet to help kids with the mental side of the game. Larry thought about it later, that my career might be enough content for a book, so one day he called me and made the case that it might be worth doing. I’m excited, he did a really nice job.

JJ: Reading it, I was struck by the unlikelihood of your career, starting with your decision to stay with your grandparents in Puerto Rico at age 11, to signing relatively late, to sticking around despite hitting .173 in your first year professionally, and battling your eye issues. Is there a common thread through all of it? Was it just the drive to be a ballplayer that made you persevere?

EM: When I was a kid, I loved the game. I used to play a lot of different sports, like basketball and golf, but nothing I liked more than baseball. I always went to the backyard to hit rocks. That was the way I used to entertain myself, and I think that developed my hand-eye coordination. All the years that I played Little League, Mickey Mantle League, Sandy Koufax League — all those leagues, even semi-pro, I was the best hitter on the team. So when it came to professional baseball, I had such confidence with my hitting. I knew I was going to hit.

Well, in Single-A, it was a shock that I hit only .173. I felt so great at the plate, but I didn’t have any results. I don’t know if that had to do with having to rotate among four third basemen, so I didn’t play every day. That fall, the Mariners gave me the opportunity to go to the instructional league, and I hit over .400, and after that I hit .303 in Single-A. From there my career started taking off.

JJ: In the book, you wrote that weight training was a real breakthrough for you. How important was that, and how different was it compared to this day and age?

EM: In my minor league career, I never lifted weights, all I used to do was jog. They used to say weights were bad for you, they restrict your movement. My first year in the big leagues (1987), one day Ken Phelps said, “You should look into lifting weights. I think that that will help you a lot,” and I took his advice. It became part of my routine, something I did pretty much the rest of my career.

JJ: I was struck by all the testimonials in the book as to your defensive ability, and the advanced statistics back that up. How important was that to your game early in your career?

EM: I was pretty good defensive third baseman through my whole minor league career. The fact that I got hurt, my shoulder and my hamstring back to back (late 1992 and ’93), I kept going back and forth to the disabled list. That’s when Lou [Mariners manager Lou Piniella] said, “We need you in the lineup as the DH, I think we can keep you in the lineup pretty much every day.”

JJ: Was it Lou’s idea to move you to full-time DH, and how did you feel when that conversation happened?

EM: I’m sure he talked to all of his coaches and the organization and they thought that was the best for the team and for me, but when we had the conversation, I didn’t want to become a DH, so I resisted moving into that role.

After, I thought for awhile. We had a pretty good team, and in Mike Blowers, we had a good defensive third baseman who could add a bat to the lineup. After thinking about all of that, I accepted and became a full-time DH, and in 1995, I won the batting title. After that, the label was on me as a DH.

JJ: What was the most important thing in adapting to that role?

EM: You have to find a routine that works, and you have to stay in the game mentally. You have to maintain a consistency in how to work out, how to prepare and stay loose, and you have to anticipate situations.

Being able to keep my mind positive all the time was very helpful, too. When you’re not doing well, if you’re playing defense you can make a play, and it may go better. But as a DH, if you’re not hitting, you’re not helping the team. That can really affect you for a while. Staying positive really helped me.

JJ: In the book, you discuss the mental aspect of hitting and I found that chapter to be fascinating. You also talk about visualization, and the eye exercises you did to deal with the strabismus. Was there a connection between those two things or was it two parallel tracks?

EM: It’s a connection, because if you anticipate a fastball, and in your mind, you know that if a fastball is coming, you see it a lot better than if you look for the breaking ball and get a fastball. So the mental side and the vision work together. That’s why when I was looking for a fastball and I got a breaking ball, sometimes I would lose it. [Martinez occasionally had difficulty tracking pitches due to his strabismus, and learned to duck his head and tuck his shoulder if he lost a pitch in mid-delivery.]

With my condition I have one eye where the muscles were weaker and not in alignment with the other eye, so my depth perception was bad. The exercises helped by keeping my eye muscles working together. So I would do all these exercises and do mental exercises as well, like affirmation to keep my inner voice very positive all the time. These two things were very helpful throughout my career.

JJ: You excelled at on-base percentage before Moneyball, before it was really cool. How conscious of that were you at the time? I know that a .300 batting average was the goal for most hitters, and that you set your sights even higher, to .350. How conscious were you of the .400-plus on-base percentages year after year, which you reached even more often than you hit .300 [11 times versus 10]?

EM: I didn’t concentrate too much on on-base percentage. I concentrated at-bat by at-bat and pitch by pitch, I didn’t think too much of the results.

It was more focusing on one pitch to hit. I wasn’t a hitter who would swing at the first pitch a lot. I hit deep in the count, I worked the count, but I always stayed on the fastball and I think that also helped to keep the zone smaller. That kind of approach helped me to focus on the middle of the field instead of one side.

What also helped me to have a good strike zone was that I didn’t swing for home runs. My approach was more sound mechanics and solid contact, with a good swing path — that will give me the ideal result. Sometimes when we try to make a big swing, we expand the zone because we’re thinking about hitting the ball too hard or hitting a home run. That’s when we swing out of the zone. The more controlled the hitter is, simplifying with sound mechanics and trying to make solid contact, the less he expands the zone.

All of those things were part of my approach and helped me to be consistent. The result was a higher on-base percentage and higher batting average.

JJ: How much pressure was on that 1995 team given the state of baseball in Seattle? [In September, as the Mariners were on the verge of erasing their 13-game deficit behind the Angels, King County voters rejected a sales tax to subsidize a new ballpark to replace the dilapidated Kingdome, raising questions about whether the team could remain in Seattle.]

EM: You know, I don’t think the team felt pressure. I think it was the opposite, more drive to win. We thought that we had a very good team and the second part of the season we were playing well. I felt that we got more focused on what was happening on the field, on winning games, and less focused on what was going on outside with the potential for the team to move to Tampa.

JJ: You had the big Division Series against the Yankees that year, and your series-winning hit in particular is obviously is a huge moment in Seattle sports history. How does it feel to be remembered for that series-winning hit?

EM: We lost that first couple of games in New York, but we were playing so well throughout the whole month of September that we didn’t feel like we were going to lose the series. We knew it going to be more difficult, but we felt that going back to Seattle that we still had a chance to come back in the series and push for the final game.

It all happened so long ago, but once in a while, people remind me of that series and what it meant to them and to their families. It was definitely a cool time, and that series was one of the best I’ve seen. It was the first one that I was in, but it was a better series than all the others I played.

JJ: You stayed with the Mariners as Randy Johnson, Ken Griffey Jr., and Alex Rodriguez left town due to salary and contract issues. Was it demoralizing to watch them depart, and did you feel like you might be better off elsewhere?

EM: It was hard at the beginning. You know, you’re losing friends that you’ve play with for a long time and they’re part of the core of the team. At the same time, we all understood that this is a business and these things happen. It’s difficult, but you have to move ahead and see what was next. It did cross my mind that probably I would be next to leave but it never happened, and I ended up staying in Seattle for the rest of my career.

JJ: Do you regret not getting a chance to play in the World Series by going elsewhere, or do you feel like it was more important to stay in Seattle and connect with the fans and the franchise and your roots?

EM: I wanted to make it to the World Series with the Mariners, and I never gave up on that. It motivates me to help the organization get there. I just felt that it’s the team that I belong to and I wanted to to make it happen for them.

…

Martinez and I spent the remainder of our conversation discussing both fellow DH David Ortiz (who called Martinez “one of the greatest hitters that played the game… beautiful to watch” in the book cover’s sole blurb) and his own election to the Hall of Fame. On Ortiz, who began his professional career with the Mariners in 1994 and was traded to the Twins two years later, Martinez said, “I didn’t get to know him when he was in the organization,” but added, “I really admired what he did through his career. Three times he went to the World Series.” Regarding his recent shooting in the Dominican Republic, Martinez said, “I hope he’s doing okay and that things are going to be okay for him.”

On his long wait for the Hall, Martinez was initially optimistic when he received 36.2% in 2010, his first year on the ballot: “At the beginning it looked like it was going to be an opportunity, then the percentage dropped down quite a bit. When it dropped [as low as 25.2% in 2014], I thought, okay, this is not going to happen, but the next few years I started moving up and I got hope again. The last couple of years, I felt this has really good chance to happen. So it was kind of up and down. It’s an incredible process for sure.”

Martinez was helped by the elections of Johnson (2015) and Griffey (2016), both of whom endorsed his candidacy — as did some other notables. “I think what Junior said really helped, as well Randy, even Mariano [Rivera], Pedro [Martinez], all those comments were very helpful for my case.”

“It’s a great honor to be part of that class,” said Martinez of being elected alongside Rivera, Roy Halladay, and Mike Mussina. “I competed against Mariano for many years and have a lot of respect for him. Great person to go in with,” he said of the all-time saves leader, against whom he hit a jaw-dropping .579/.652/1.053 in 23 career plate appearances.

Most of that success came before Rivera had discovered the cut fastball that would carry him to Cooperstown, and similarly, much of his damage against Halladay (.444/.474/.722 in 19 PA) came before the pitcher became an All-Star. “What I remember is his stuff, how it moved in two directions and it was heavy. Good stuff — sinker, cutter, and a good breaking ball — good velocity, good arm. One of the best pitchers I faced.” As for Mussina, whom he faced 83 times, hitting .307/.337/.627 with five homers, the most he hit against any pitcher, “I was kind of up-and-down with Mussina. He was hard to to figure out. He mixed a lot and changed the look and didn’t have a lot of patterns.”

If you’re scoring at home, that’s a combined .375/.416/.714 line in 125 PA against his Hall of Fame classmates, further proof that Martinez could hit even the best. For that, he’ll be inducted into the Hall of Fame next month, capping a baseball fairy tale.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

I get that it’s not awesome to have your teammates leave, but the Mariners weren’t exactly chumps after Randy, Junior, and A-Rod left. They won 116 games in 2001.

My favourite shot in Moneyball is when Peter Brand is explaining the Pythagorean record to Billy Beane, and on the whiteboard in the background you can see the Mariners’ 300-run differential from the previous year.