Edwin Díaz Is Going Supernova

The New York Mets acquired Edwin Díaz in a trade with the Seattle Mariners before the 2019 season. At the time, the deal was controversial, to put it charitably. Díaz was coming off a breakout 2018 season, one that established him as the best young reliever in baseball. He struck out 44.3% of his opponents en route to a 1.96 ERA (1.61 FIP, 1.78 xFIP) and had four years of team control remaining.

That combination of skill and value doesn’t come around often, and the Mets paid dearly for it. They took Robinson Canó and his contract along with Díaz, and sent multiple prospects back in the bargain, headlined by Jarred Kelenic, their previous year’s first round draft pick and a consensus future star. Things went quite poorly for New York out of the gate; Kelenic flew through the minors, Díaz posted a 5.59 ERA in his first season with the Mets, and Canó had his worst season since 2008.

You probably already knew all of that. It wasn’t exactly a small story at the time, and when Kelenic debuted at the start of the 2021 season while Canó was serving a suspension for violating the league’s performance-enhancing drug policy, the “Mets snatch defeat from the jaws of victory” headlines reached a fever pitch. But with the benefit of 15 more months of games, and also as someone who isn’t particularly good at hot takes, allow me to add this to the discourse: Edwin Díaz is really good.

It’s easy for a reliever to get lost in the mix these days. Everyone throws 99 to go with a slider that will make you question your understanding of the space-time continuum. When the sixth guy out of a mid-tier contender’s bullpen does that, it stops being quite so impressive. But, well, Edwin Díaz throws a 99 mph fastball that makes those other 99 mph fastballs look lethargic. And his slider? If Isaac Newton had seen it, I’m not sure he would have come up with the laws of gravity, because the pitch refuses to abide by them.

When assessing Díaz, we might as well start with the fastball. Velocity alone simply isn’t a difference maker in baseball these days. Díaz throws 99, sure, but it’s how he throws that 99 that matters. The first thing you’d look for in a dominant fastball is excess vertical movement. If a pitch has enough pure backspin, velocity is almost an afterthought. That isn’t the case for Díaz, though. He throws with pure over-the-top spin, but releases from a low arm slot. The result is a two-plane fastball; it spins perfectly off his fingers at release, but that results in both rise and fade. To wit, his fastball falls three inches more than Josh Hader’s on its homeward path despite having less time to fall thanks to its superior speed.

So fine, Díaz doesn’t have game-breaking vertical movement. But the pitch has two other things going for it. First, that horizontal run still exists. It might not be as efficient at missing bats, but more movement is hardly a bad thing. Second and more importantly, that low arm slot combined with his superlative velocity leads to one of the shallowest-angled fastballs in the majors.

This season, 639 pitchers have thrown four-seamers in the big leagues. Díaz has the 16th-shallowest vertical approach angle in the bunch, and six of the pitchers in front of him use some flavor of sidearm delivery; another six have thrown 10 or fewer four-seamers. In addition, only Andrés Muñoz throws harder and with a shallower angle. Díaz’s fastball, in other words, stands out even among the sea of excellent major league fastballs.

Shallow vertical approach angle, particularly high in the zone, leads to whiffs and strikeouts. It’s fairly intuitive – if the ball is on a shallower plane as it approaches home plate, hitters commit to swinging at worse pitches, expecting them to fall more than they do. In addition, they swing under them more frequently; they’re targeting the wrong pitches, after all.

For a visual representation of what that looks like, let’s pick on Nick Castellanos. Here he is swinging just under a 101 mph fastball to close out a Mets-Phillies contest in May:

Díaz is a blur of arms and legs when pitching, but in a freeze frame, you can see why his release point leads to a shallow approach angle:

Right, so, explosive fastball. That’s a great first pitch to have, and it explains why Díaz is in the 90th percentile for swinging strike rate among pitchers who have thrown at least 100 fastballs this year. But it’s not enough to make him a dominant closer; in fact, batters have performed admirably against his fastball so far this year, doing enough damage when they make contact to offset all those swinging strikes. They’re slugging .486 against the pitch, and though the underlying contact quality isn’t quite that good, the equation still isn’t a comfortable one for Díaz.

Enter his slider. In my opinion, it’s the best breaking pitch in baseball. It isn’t one of those new-fangled sweepers, darting suddenly right-to-left. It doesn’t have great depth, dropping out of the strike zone like a curveball. It’s just an optical illusion: a hard (90.3 mph on average) pitch that looks just like a fastball, right up until it doesn’t. Throw a baseball that hard, and spin should impart movement in some direction. Díaz’s pitch hardly breaks, which means that it moves a ton relative to expectations – instead of riding and fading, it dips due to gravity and has a tiny bit of horizontal break.

It’s easier to see in motion than in words, so let’s just do that. If Díaz starts it low, it looks like a middle-height fastball before disappearing below the zone:

If he starts it just a little bit higher, it looks like an upper-third fastball right up until it doesn’t:

And finally, he can mimic his above-the-zone fastball, a pitch batters are already primed to look for. The slider starts high before parking itself dead center:

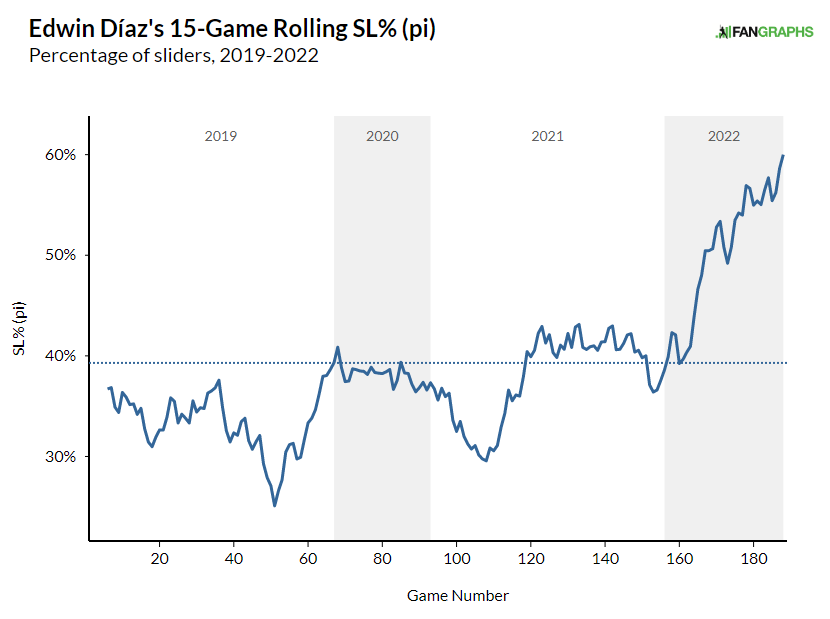

There’s no doubt about it: the slider is the better of Díaz’s two pitches. This year, he’s leaning into it:

Since the start of June (an endpoint I picked more or less at random), Díaz has thrown 60% sliders and 40% fastballs. Why wouldn’t he? The results speak for themselves; he’s running a 28.1% swinging strike rate on the pitch this year, a number that I frankly have trouble wrapping my mind around. Batters are making contact on half of their swings against it, and they’re not even picking good spots to swing: they’re chasing 50% of his out-of-zone sliders, wildly above league average, while swinging at only 67.2% of them in the strike zone. Heck, even when they get it right – swinging at a slider in the zone – they’re coming up empty 30% of the time.

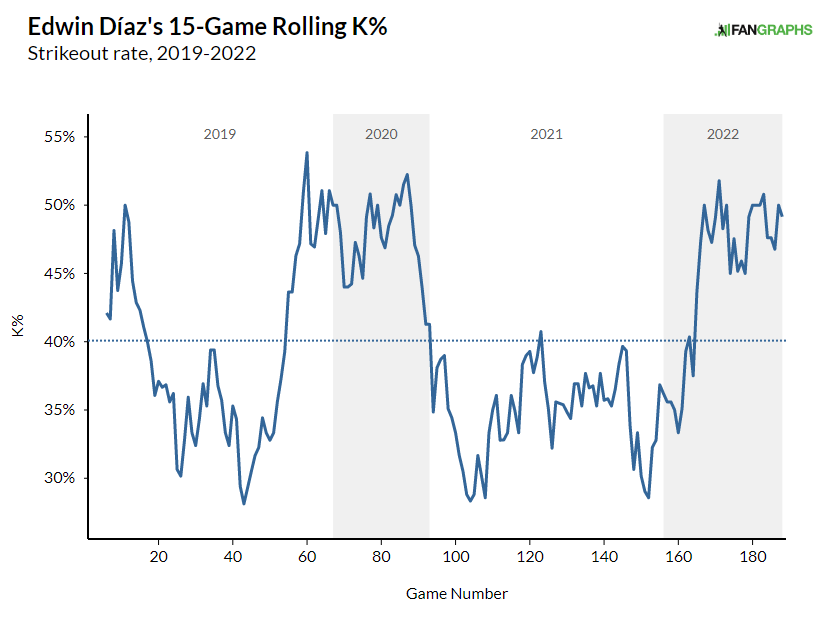

Want to know what that’s doing for his strikeout rate? You don’t have to be a baseball analyst to guess:

After a down 2021 (from a strikeout perspective, that is — his overall line was still excellent), this increased slider usage has kicked Díaz’s strikeout game back into overdrive. It’s been well timed, too; the Mets are suddenly locked in a tight divisional race, just a few games ahead of the surging Braves. Their starting pitching received a shot in the arm with Max Scherzer’s return, but it’s been shaky of late. The offense is struggling.

With that backdrop, you’ll need to win your close games to keep the pace, and Díaz has been a trump card there. He’s made 12 appearances since June 1; he’s allowed exactly one run, and it was in a game where the team had a two-run lead to work with. The Mets have won 10 of those 12 games. The other two weren’t exactly disasters; he came in once to get some work (trailing 5-3 in the eighth) and once to preserve a scoreless tie (Drew Smith surrendered a tie-breaking two-run homer the next inning).

Closers aren’t inextricably linked with a team’s success. You can have a good closer on a bad team and vice versa. But right now, the Mets badly need someone to nail down their slim leads, and you can make the case they have the best closer in the game to do just that. You can argue about the cost, and you can argue about the contracts, but put it this way: the Mets wouldn’t have been able to acquire a better closer than Díaz, regardless of cost. That player simply doesn’t exist, short of the Brewers unexpectedly trading Hader. For this team – a World Series contender with stars aplenty – Díaz is the perfect complementary piece, capable of turning a nice start into a win or holding the line long enough for the offense to do their part.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

I still think the trade was an incredibly poor process by a horrendous gm, but that doesn’t mean Diaz isn’t now amazing now because he is obviously, as his strike out rate is incredible and kudos to whoever told him to throw the slider more. Diaz seems to have more control and command of his slider than he does of his fastball. He was a gopher ball machine his first year and played a big part in the Mets missing the playoffs in 2019 as did almost every reliever not named Lugo that year, but as far as Diaz I think the juiced ball killed him. He just bullies hitters these days and a joy to watch and will be a big part of a Mets run if they go deep n the playoffs. I think my fav matchup he had was when he just overwhelmed Trout and went on to strike out all five batters he faced vs the Angels a month or so ago.

Keep in mind that Brody was hired solely because (unlike Chaim Bloom who reportedly said they would need to rebuild) he was the only one who claimed he could make the Mets a playoff contender despite strict payroll limitations.

It was still a terrible trade, but it was a rather clever trade in that the Mets acquired Cano and Diaz without increasing payroll. Had Brody been able to raise payroll, I doubt that trade is ever made.

And had Cano and Diaz merely played to their career averages instead of sucking, the Mets are a playoff team in 2019.