Errors and Omissions: Fixing the Line Score

Admit it: you don’t like line scores. If you look at them, it’s only in passing, or to make yourself a little angry (the indignant kind) after a game your team lost. Nine hits, and we only scored two runs?!? The other team scored four runs on four hits?!? There ain’t no justice. They even made an error, and we kept a clean sheet! How could this have happened?

Of course, if you weren’t looking at a line score, you probably wouldn’t make either of those complaints, because it’s unlikely that which team made an error had that much of a bearing on the outcome. And that’s a shame, because the line score should be a great source of information. It’s an ingenious construction – tons of data conveyed in a compressed format. The inning-by-inning scoreline gives you the dramatic beats of the game – who scored when, whether it was a comeback or a wire-to-wire romp, and so on. The smattering of information on the right tells you roughly how the runs scored with great efficiency.

Or at least, it should tell you how the runs scored. The problem is, it really doesn’t. Take this one (courtesy of Baseball Reference), from an April 1 tilt between the Astros and Athletics:

The Astros barely out-hit the A’s. They played atrocious defense. They won by seven runs anyway. That’s because a single and a double (or a triple or a home run) count the same under “hits.” Meanwhile walks don’t count anywhere but errors, which occur far less frequently than walks and produce similar results, take up a third of the available real estate. Home runs matter more than either, and are nowhere to be found. Let’s look at a more complete tale of the tape for this game:

| Team | 1B | 2B | 3B | HR | BB | HBP | ROE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astros | 4 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| Athletics | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

Houston had three more extra-base hits. They reached base on non-hit outcomes more often than Oakland. Look at that list, and it’s obvious who won this game. Maybe you wouldn’t expect it to be quite the blowout it was, but Houston had five extra baserunners and slugged .545 to Oakland’s .267. That’s a rout – not this:

| Team | Hits | Errors |

|---|---|---|

| Astros | 9 | 2 |

| Athletics | 6 | 0 |

Of course, fixing that is easier said than done. The extensive categorical breakdown from above won’t work for a line score, because it’s far too much data. Whatever the line score’s faults, you can’t knock it for brevity. The reason it’s still posted for every game is that it takes up little space but provides useful context.

I have a solution to that. Can you fit all the categories I care about into two lines? Definitely not. But an approximation doesn’t have to be very good to beat the old standard of hits and errors. My solution? Group every one-base event into one pile and every multi-base event (with one exception I’ll explain shortly) into another. Let’s call them “1B” for one-base events and “XB” for extra-base events. Now the result makes more sense:

| Team | Runs | 1B | XB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Astros | 8 | 12 | 5 |

| Athletics | 1 | 10 | 2 |

The one exception to the dividing line I proposed is errors. Most errors are of the one-base variety, but they come in all kinds of flavors, from dropped foul balls that don’t even produce a baserunner all the way up to four-base errors. You could put these into the correct categories, but I think the added precision isn’t worth the extra fiddling. Most errors cost a base, so throwing them all into the one-base bucket is close enough for our purposes here.

Normally, this is the part of the FanGraphs article where I present data to support my argument. In this case, though, I don’t think data would be particularly useful. What data would you want here? Times I’ve looked at a line score and thought “the wrong team won this game” in error? Empirical estimates of how much happier you’d be knowing that your team socked five extra-base hits rather than looking at an inscrutable line of eight hits and two opposing errors and wondering how they scored nine runs?

The real gain in this is that we would care more about line scores, and they’d tell us more about what happened on the field. What do you think happened in this matchup between the Rangers and A’s?

After making up your mind, let’s look at it in our new format:

| Team | Runs | 1B | XB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rangers | 5 | 9 | 2 |

| Athletics | 10 | 19 | 2 |

Now you’re getting it. The A’s juiced the bases all game long. They put a six-spot up without an extra-base hit in the second, and didn’t hit a single home run. They were fairly efficient with their baserunners, in the grand scheme of things. It’s a lot easier to score those one-base advancements if you’re clocking the ball into power alleys or over the fences, but that stops being true when you run a .455 OBP as a team.

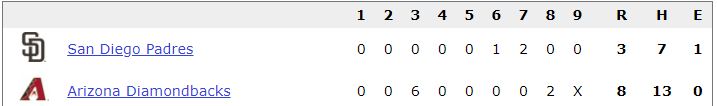

Or take another one, Padres-Diamondbacks from September 1, with both teams sputtering but the Padres still nine games over .500. Arizona won, and you’d be forgiven for thinking it looked like a standard rout:

But the Padres had some pop in this one. Let’s see it in our new format instead:

| Team | Runs | 1B | XB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Padres | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Diamondbacks | 8 | 19 | 3 |

This game was actually intriguing. The Padres slugged the ball all over the park, with two homers and three doubles. But Arizona, led by starter Luke Weaver, limited the damage – not allowing a single walk helps, as does running a BABIP below .200 – and so the Padres got nearly nothing to show for their big knocks.

Meanwhile, the Diamondbacks overwhelmed the Padres with hits both small and large. They put a baserunner aboard in every inning, and while they mostly squandered them, they did manage to string together a pile of baserunners in the second inning to make it a walkover.

Not every game would be enhanced by a more descriptive line score – I picked some evocative ones on purpose – but providing more useful information in the same space can’t be a bad thing. Yes, after all this, I think that the line score is a great idea – just one whose execution could stand improving.

The Hall of Fame credits Henry Chadwick with inventing the box score and line score in 1858. That’s amazing! The game – and even more so, the world – have changed many times over since then. For decades, box scores changed with them. More categories were added, statistical summaries jumped in below the box score, and when the RBI was developed, it became a full-box-score mainstay.

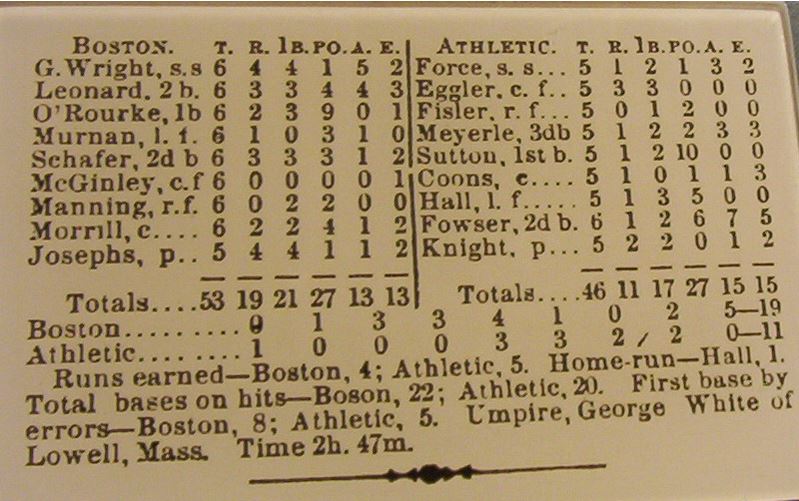

But aside from those early innovations, line scores have remained static. Nothing has changed even as the way baseball is played has evolved into something that would be nearly unrecognizable to a fan from the 19th century. Errors aren’t one of the most important statistics in the game anymore. That wasn’t always the case – look at this wild box score from 1876 I sourced from Wikimedia Commons:

In a game with 28 errors (and 13 “first base by errors”), devoting a third of the line score space to errors makes perfect sense. As best as I can tell, there were two extra base hits in the game – a column for extra bases would have looked like the error column does today, a strange vestigial limb. A line score of this game, in the original runs/hits/errors form, does exactly what my proposed change would do today: encapsulate the most important events with a concise presentation.

In fact, I’ll go out on a limb: if Henry Chadwick were alive today and following baseball, he’d change the line score. He had a genius for presenting information, and in modern baseball, how often you’re walking and hitting for extra bases – or preventing the opposing team from doing so – has a lot to do with winning, so I’m sure he’d want to see it.

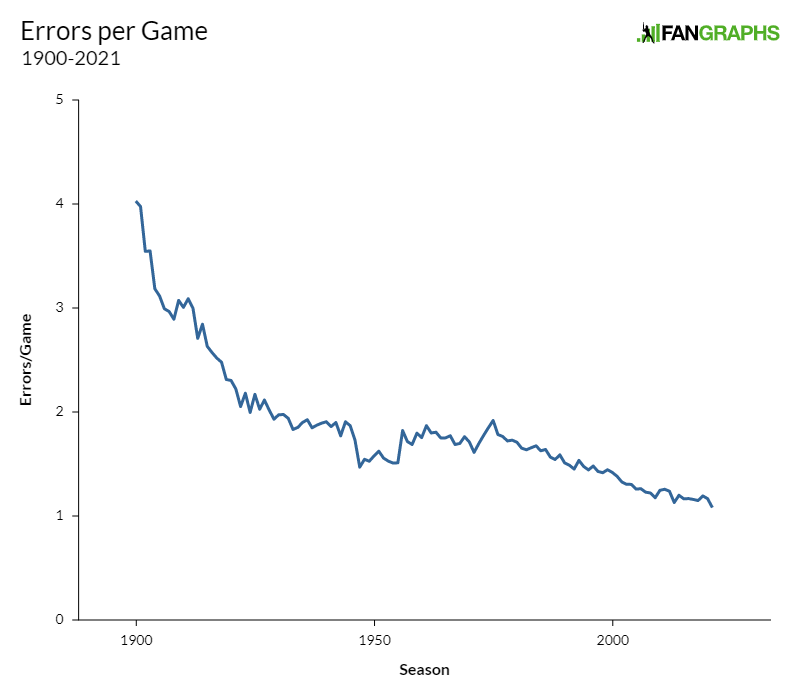

Would his line score change mirror mine? I have no idea! But he’d surely do something. Errors have been sitting there, occupying space on pages and in minds, while their frequency has plummeted:

So let’s end the tyranny of the error and remove it from line scores. Let’s replace it with something better, and get walks in there while we’re at it. I’m not sure how to propose this change more widely. I don’t run Baseball Reference, or ESPN, or wherever people get their line scores. I’m open to ideas for how to talk about this more. But I really do think that this change would improve my consumption of baseball. I look at a lot of line scores in a year. It’s about time that they showed me the data I really want.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Thanks, Ben, I like this idea! Would you just include hits, errors, bases on balls, and hit by pitches in the 1B column? Or would you also include things like catcher’s interference (maybe that already counts as an error?), reaching on a dropped strike three, or a fielder’s choice where nobody is put out?

I’m open to doing either, but I think my default is to keep it simple in general. Catcher’s interference is already an error, so that’s covered — but maybe the fielder’s choice-type plays could be handled by the below suggestion (by g4) of a ‘total baserunners’ column? I do think that most FC’s that don’t result in an out are due to error, so it would be a pretty small addition.

I like the total baserunners idea.

As an aside, I know it is not common, but it is a pet peeve of mine when everyone is safe and it is scored a fielder’s choice. I am perfectly fine with a fielder’s choice where the fielder gets a different baserunner out and the batter is safe. But when everyone is safe, I strongly feel it should always be ruled either an infield hit or an error and I fail to see the logic behind a fielder’s choice where no one is out.

💯

The logic is that the batter would’ve been thrown out at first base had it been thrown there. The defense took a risk, and it didn’t pay off, but they didn’t actually commit an error; while the batter didn’t have anything to do with that defensive decision, so he shouldn’t get credit for it, either.

Then roll such cases into the long-proposed “team error” category (along with popups landing in between 3 fielders and such).