Eugenio Suárez Needs More Power

Eugenio Suárez is not a major league caliber shortstop. That’s no knock on him — pretty much no one in the entire world is, and he picked the position up out of necessity rather than because it was in his range. The Reds simply had no one to play there, and he looked like the least terrible option. The experiment didn’t last long — 32 games was enough to say that he was better suited for third base — but the team’s changed infield construction gave Jonathan India a big league shot, so it wasn’t all bad.

The hitting, on the other hand? That’s been all bad. Suárez has been restored to his natural spot at third base, and the Reds are mounting a playoff charge — but they’re doing so despite an absolutely abysmal season from the player we projected as their best before the season started. He’s hit .172/.259/.373, good for a 68 wRC+, and it’s worth asking whether this is just a blip on the radar or the beginning of the end for one of the sneakiest power hitters of recent years.

Let’s start with something that doesn’t seem to have gone wrong: Suárez is still hitting home runs at a solid clip. A full 18.3% of his fly balls have turned into homers this year, and while that’s not quite the rate he managed in 2019 or 2020, it’s still an excellent number, one that makes sense given how hard he hits the ball and the bandbox park the Reds call home. And he’s doing so despite a nagging shoulder injury that has plagued him since the start of the 2020 season.

In 471 plate appearances so far this year, Suárez has cranked 23 bombs. Plug those home run numbers in and use previous career rates to fill in the rest of his statistics, and he’d be doing just fine; he’d be hitting roughly .263/.344/.480. There’s all kinds of absurd math in there, and I’m not claiming that’s a reasonable projection for the season, but the power certainly hasn’t been the problem this year — at least at first glance.

Cast your eyes anywhere else, though, and you’ll see some ugly numbers. Striking out 30% of the time isn’t the unbelievable disaster it once was, but it’s certainly not good. Suárez doesn’t need to have great plate discipline to thrive — those home runs are useful — but more strikeouts means less margin for error. When he struck out 28.5% of the time in 2019, it was fine, because nearly 30% of his fly balls left the park. Downgrade the power from exceptional to plus, and those strikeouts start to sting.

Similarly, Suárez’s walk rate has eroded — albeit from strength to neutral rather than from neutral to weakness. He’s not reaching base for free the way he was earlier in his career; his 9.8% walk rate is down to 9%. That’s a much smaller change than the strikeouts, but it’s pointing the same direction — more things that power has to make up for.

Finally, we’ll get to the real culprit. When Suárez makes contact but doesn’t hit a home run, there are no two ways about it: it’s an absolute disaster for the Reds. Honestly, disaster might be underselling it; 253 times this year, Suárez has put the ball in play. He’s batting .196 with a .192 wOBA on those balls. Out of context, you might not know how bad that is, but it’s disastrous. Last in baseball by a big margin disastrous, in fact:

| Player | Events | BA | wOBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eugenio Suárez | 253 | .196 | .192 |

| Carlos Santana | 325 | .234 | .216 |

| Maikel Franco | 292 | .228 | .225 |

| Kyle Seager | 294 | .234 | .228 |

| Kevin Newman | 356 | .241 | 0.233 |

| Andrelton Simmons | 272 | .249 | .233 |

| Max Kepler | 214 | .227 | .233 |

| Jorge Soler | 235 | .237 | .233 |

| Wilmer Flores | 245 | .248 | .236 |

| Gregory Polanco | 204 | .253 | .237 |

I won’t sugarcoat it: this is terrible. Comparing him to 2021 undersells it, too. It’s the worst performance on balls in play since the beginning of the Statcast era, whether you care about wOBA or batting average. Everything else is window dressing; if we want to find out what’s wrong, we’ll have to find out what’s going wrong after he makes contact — and, crucially, whether it’s likely to keep weighing him down going forward.

The first key to good contact is to avoid the extremes. Smash a ball straight into the ground, and the odds of a positive outcome are low. The same is true for one launched too high into the air. More specifically, balls hit below zero degrees of launch angle lead to a .175 batting average and .159 wOBA. Balls hit higher than 40 degrees are even worse, generating a .040 batting average and .049 wOBA. Everything else comes out to a .464 batting average and .539 wOBA. Avoid the mishits, in other words, and you’re sitting pretty.

That would be a nice clean narrative, but Suárez isn’t particularly bad at hitting the ball on the screws. He’s in the 40th percentile league-wide; 60% of hitters hit fewer balls too high or too low. That’s not a great place to be, but it’s hardly what you’d expect from someone having a historically bad season when it comes to results on balls in play.

What gives, then? One clear culprit is a pitiful line drive rate. Line drive rate is noisy — being good at it one year doesn’t say a lot about your future performance, though some hitters clearly do have a talent for hitting them (Freddie Freeman says hi). Before this year, Suárez seemed to fall into the group of batters who are neither good nor bad at hitting liners; his career 22.3% rate is a hair over average. This year, though, he’s checking in at a pitiful 15.6%.

What counts as a line drive is a matter of judgment, but the numbers don’t look great. Statcast has a number called Sweet Spot Percentage that measures the percentage of batted balls hit between 8 and 32 degrees; broadly speaking, that’s line drives and low fly balls. From 2016-19, Suárez consistently checked in around 40%. In 2020, that number fell to 32.6%, and it’s at a new career low of 31.9% so far this year.

When I looked at year-to-year correlation of line drive rate before the 2020 season, I found that line drive rate mostly regresses to the mean from one year to the next, and though I didn’t look within years, it’s hardly a stretch to imagine that the same thing might be true within a single season. So that’s it! We’ve cured him, and everything is back to good now, right?

Well, no. First of all, a few extra line drives wouldn’t really fix everything. Second, these numbers are aggregates, not things true for every player. Every batter’s line drive rate fluctuates, and on average they mostly return to average, but if a hitter is taking some action that leads to fewer line drives, it’s reasonable to assume those line drives won’t come back until he changes his behavior. Let’s dive a little deeper rather than rely on some blanket rule, shall we?

Suárez’s recent power spike coincided with something meaningful: he started elevating more balls. As Alex Chamberlain noted in a look at spray angle, Suárez is approaching the ball much more steeply than he did in 2018, before his recent power spree. That’s a great way to hit more home runs, but it comes with a caveat: if you’re lifting the ball, you’re going to want to pull it as well.

That’s true for myriad reasons, but the simplest one is this: if you pull and elevate the ball, you’re generally hitting it harder. When you’re hitting the ball in the air, quality of contact matters much more; soft grounders can turn into hits and hard grounders can turn into outs, but the same mostly isn’t true in the air.

Lo and behold, Alex’s spray-angle-adjusted hard hit rate can explain what went wrong. His formula accounts for the fact that batters hit the ball harder when they pull it, and after accounting for that, Suárez’s hard hit rate hasn’t moved much. His raw hard-hit rate has plummeted, though, and it’s because he’s pulling fewer line drives and fly balls:

| Year | Air% | Air Pull% | Air Hard Hit% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 58.1% | 21.2% | 37.6% |

| 2016 | 58.4% | 24.5% | 35.3% |

| 2017 | 60.5% | 28.7% | 40.9% |

| 2018 | 60.6% | 30.4% | 46.4% |

| 2019 | 64.0% | 41.4% | 45.8% |

| 2020 | 63.6% | 38.1% | 52.4% |

| 2021 | 61.2% | 35.5% | 43.2% |

None of these numbers look huge, but they all add up. Recall, also, that his line drive rate has dipped — that’s another form of authoritative contact. All of the data seems to be saying the same thing; though his top end contact is unchanged, he’s getting to it less often. That’s not to say he’s barreling the ball up less; in fact, his barrel rate is as good as ever. But you can make valuable contact without meeting the textbook definition of a barrel, and Suárez simply isn’t making much of that anymore — his share of hits that are “solid contact” or “flare/burner” is at a career low.

To me, this implies that he’s playing hurt. When his swing is perfect, he still mashes. He simply isn’t repeating it as much. That’s a difficult thing to diagnose, because “doing something but not all the time” is basically all of baseball. I have a theory, though: you can see Suárez’s injury in his inability to crush fastballs.

See, Suárez is a fastball hitter, and always has been. In his career through 2020, he accrued 66.7 runs above average against fastballs, and basically zero total runs against all other pitches combined. That’s a great way to get ahead, because pitchers can’t exactly avoid throwing fastballs. Wait them out, get into fastball counts, and hit pitches over the wall; it’s a time-honored plan.

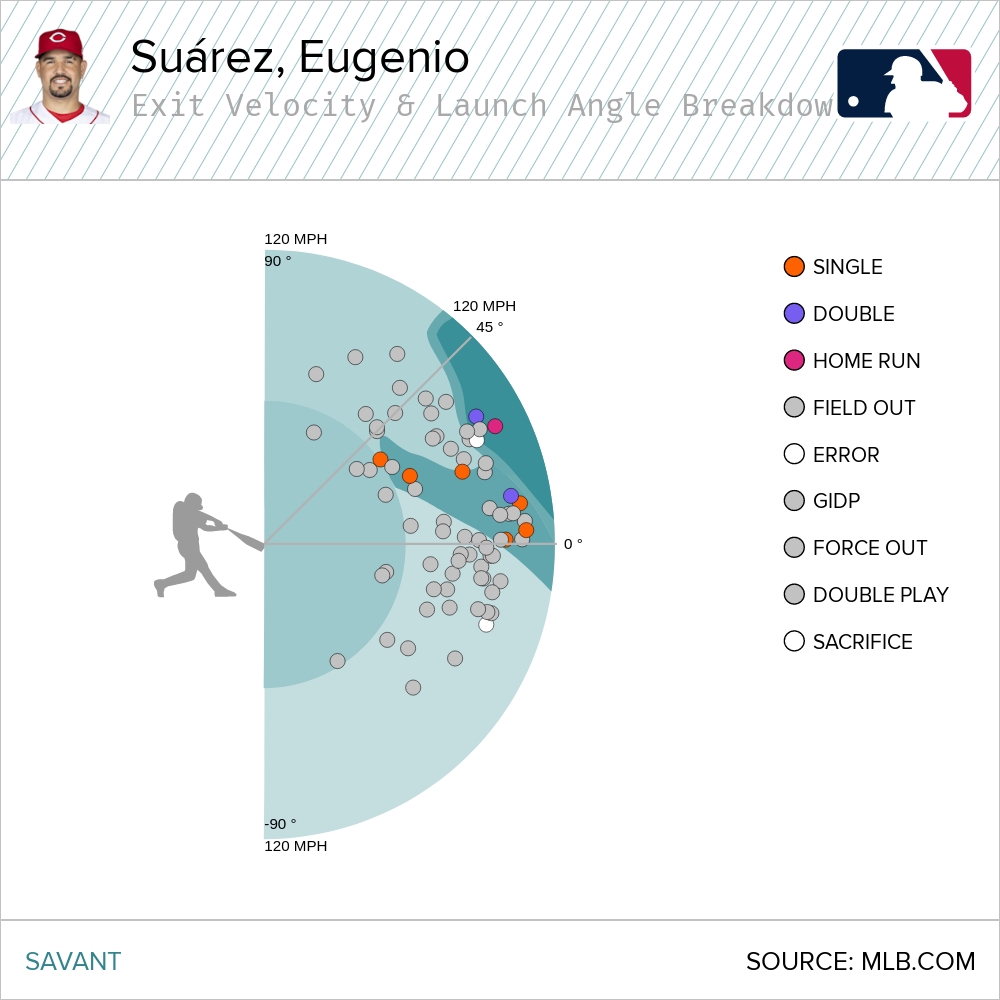

Yeah, uh: Suárez has been 14.1 runs below average against fastballs this year, and his biggest problem has been with sinkers. The easiest way to show what’s going on here might be with Baseball Savant’s radial charts. Here he is in 2019:

He didn’t hit a ton of doubles, but he still did what he needed to, turning on enough sinkers to fill up his cup with home runs. Compare that to 2021, and his shortcomings are clear:

It’s not just the homers, though. He’s never made such indifferent contact against sinkers; there aren’t that many batted balls in the teal area that corresponds with medium-hit line drives. That’s a key part of any plan of attack against sinkers, because you’re not going to be able to hit them all over the fence.

I thought that this might be a problem of velocity. Maybe Suárez can’t catch up to the heat with his hurt shoulder. Some corroborating evidence: he’s put up his worst production on fastballs thrown 95 mph or harder this year. But that’s only by a hair, and he’s been wildly bad against fastballs thrown under 95 mph. It’s a systematic problem, not merely one with exceptional pitches.

I won’t lie to you, I’m not particularly happy with the conclusions I reached here. It’s pretty obvious that Suárez isn’t hitting the ball as well, barrel rate notwithstanding, and I’m not sure I truly unearthed something new by digging into his batted ball data.

In fact, if I’ve learned anything, it’s that I don’t quite understand how he was so great in 2019. He became a markedly different hitter that year, with fewer line drives and more fly balls pulled more often. It’s a cliché, but he joined the air ball revolution. That worked, but it didn’t work because he kept hitting like his earlier self and added power — it worked because he changed the way his game worked entirely.

That thing I did at the top where I said that Suárez’s home run rate is roughly in line with his career-to-date numbers was misleading. In 2019 and ’20, he hit home runs in 7.2% of his plate appearances. That gaudy total made his overall line sing, but it obscured some real under-the-hood changes. He really is a low-average guy now; he’s not a true-talent .173 hitter, but he hasn’t had an xBA above .245 since 2018. That’s Statcast’s measure of batting average based on batted ball velocity and vertical angle, and while it’s not a perfect proxy, it tells the story we’re looking for: Suárez traded average for power, and it paid off.

He almost certainly won’t continue to be this bad. He’s been unlucky in addition to hurt; he’s hitting .477 on flares and burners this year, the lowest average of his career by nearly 200 points (league average is .650). He’s made “solid contact,” another Statcast definition, eight times, with no extra bases to show for it. In his career before this year, 37.5% of his solid contact had gone for extra bases.

But don’t let these small snippets obscure the truth: Suárez needs the preposterous power he showed in 2019 to be an above-average hitter. His new game works by pulling the ball in the air. Fail to get to that with great frequency, and the rest won’t really work — maybe not to the extent of this year’s -0.7 WAR, but if you’re striking out 30% of the time and doing all your damage on pulled fly balls, you better pull a lot of them.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Image links are either broken or not showing up for me. Not sure if it’s my issue.

Ditto.