Goodbye, Mr. Baseball. It’s Ben Rice Knowing You.

When the Yankees lost Gerrit Cole and Luis Gil before the season started, I thought they were screwed. Turns out, at least so far, that New York’s stripiest sports team is right where it ended last year: First place in the AL East. That’s because the Yankees, as of this writing, lead the league in home runs, OBP, SLG, and (by a pretty big margin) wRC+. It helps that the rest of the AL East (especially the Orioles) has started slow, but the best defense is a good offense and all that.

And it’s not just Aaron Judge, who is 20% of the way through an offensive campaign that makes Babe Ruth look like Rey Ordonez. Judge can only bat four of five times a game; even he can’t do it alone. But even with Giancarlo Stanton hurt and Austin Wells and Jasson Domínguez offering only token offensive contributions, Judge has had the running buddy he needs. It’s… Ben Rice, believe it or not.

Once a sports team has been around as long as the Yankees have, and won as long as the Yankees have, patterns will start to emerge among star players across the history of the club. Think of the Lakers’ centers throughout history: Mikan, Wilt, Kareem, Shaq. Or Manchester United’s pretty-boy wingers: George Best, David Beckham, Cristiano Ronaldo.

Since I’ve already mentioned Ruth and Judge, you might think that the Yankees’ version of this historical successorship is the home run-hitting right fielder. Sprinkle in a little Roger Maris here, a little Reggie Jackson there.

All that’s well and good, but the truest Yankee is the 25-year-old rookie first baseman/DH who rakes for somewhere between six and 18 months and is never heard from again. Rice was not only a 22-year-old college catcher when the Yankees took him in the 12th round in 2021, but he’d also only played 30 games total in three years at Dartmouth, as the Ivy League not only canceled most of the 2020 baseball season, but all the 2021 schedule as well.

Rice hit his way gradually through the minors over parts of four seasons, but he never developed into a big league-quality defensive catcher. Eric Longenhagen could only place Rice 29th on the Yankees’ prospect list in his final year of eligibility.

The summary: “I was hoping to juice Rice more than this at the onset of the process for this list, but I left my film study of his defense feeling extremely bearish about his ability to stay behind the plate. There is still big time lefty bat speed here, enough to make Rice interesting as a bat-only prospect.”

So when Rice popped his head into a major league clubhouse in the middle of last year, I took notice of the fact that the Yankees had a left-handed-hitting rookie catcher/DH other than Wells. Beyond that, I filed Rice into the same mental cubbyhole previously occupied by Mike Ford, Greg Bird, Tyler Austin, Shelley Duncan, Kevin Maas… I’m counting George Selkirk too because he probably would’ve played some first base if Lou Gehrig hadn’t been on a historic ironman streak.

Some of Rice’s numbers were pretty solid in his rookie year: Seven home runs in 50 games is 20-plus homer power over a full season, and an 11.2% strikeout rate, a 27.0% walk rate, and a .178 ISO are fine. By no means is that first-division starter production, but a first baseman or DH who puts up those numbers will usually find a roster spot somewhere.

Unfortunately, those secondary numbers are all totally independent of batting average, and Rice hit .171. That won’t fly. It would not have shocked me if a 73 wRC+ in 50 games had closed the door on Rice’s Yankees career for good. We’d see him in three years hitting .200 with 25 home runs playing every day for the Pirates or something, but 25-year-old 12th-rounders with a 35+ FV don’t get that much rope with good teams.

Through Monday’s games, Rice was putting up similar walk and strikeout numbers — 11.4% and 25.2%, respectively — but everything else was a night-and-day difference from last year. Rice already has more home runs (eight) in 123 plate appearances than he produced in 178 plate appearances last year. The other less-truthful outcomes have fallen into place as well: Rice is hitting .255/.358/.557. That’s an improvement of 84 points of batting average, 94 points of OBP, and 208 points of slugging percentage.

Rice’s 160 wRC+ is not only good enough to claim a starting spot on any team in the league, it’s commensurate with a top-10 MVP finish, even for a DH.

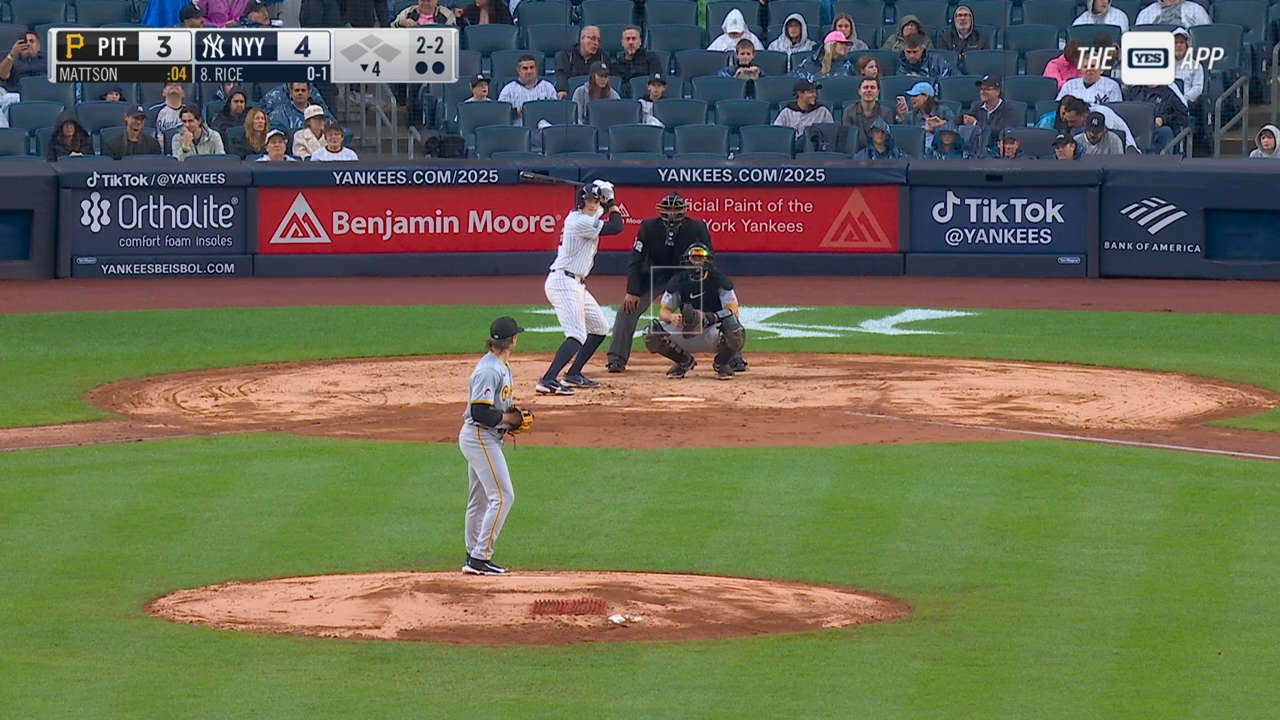

This early in the season, it’s frequently a struggle to identify which changes in a player’s game are real and which are a small-sample mirage. But not always. This is Rice’s stance at the end of 2024.

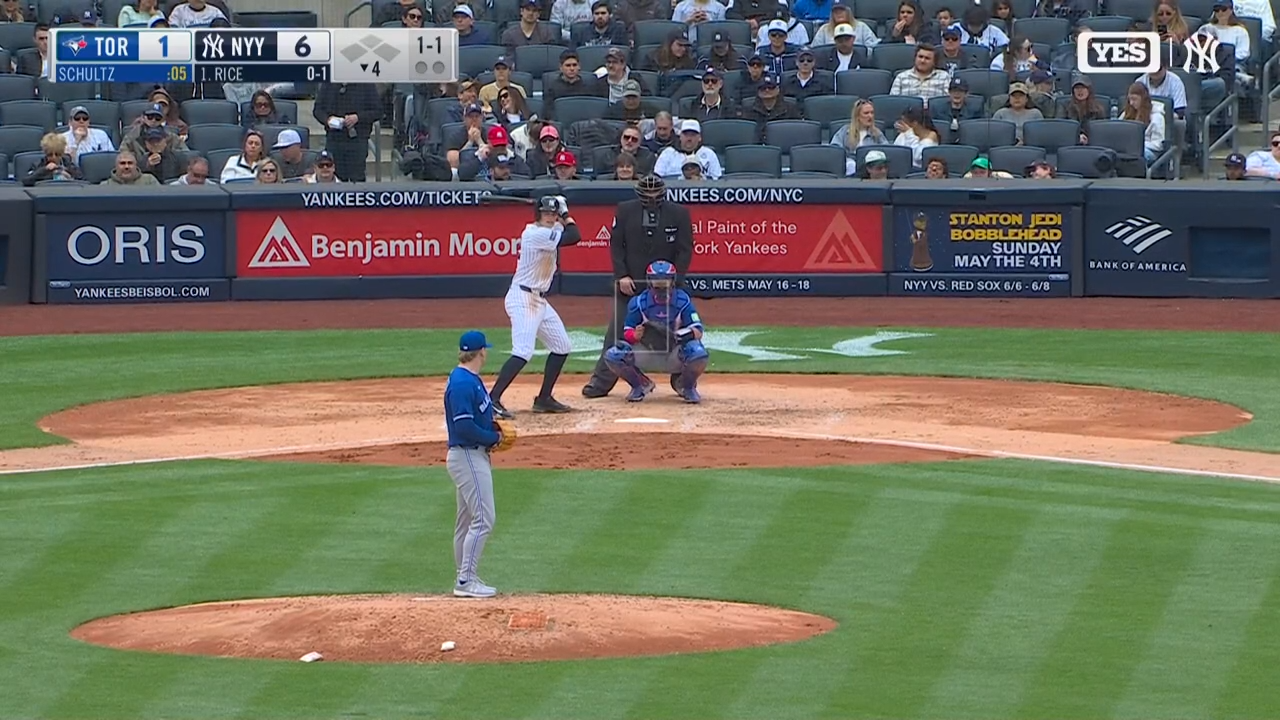

And this is his stance now.

Rice always had an open stance, which led to all sorts of desirable attributes as a hitter: That high walk rate, for one, and plus bat speed, for another. Rice has long tended to pull the ball, and to hit it in the air, and crucially, to do both at the same time. That’s how you get home runs.

Some hitters, having suffered as Rice did as a rookie, might have gone back to the lab and tried to come up with something new. Not Rice, who decided that more is better. An eight-degree open stance is now a 27-degree open stance, according to Baseball Savant.

Now, I’m from the 1990s, so when I see a guy come to the plate standing sideways with his legs splayed out like Tim Commerford on the bass guitar, my mind goes to Tony Batista.

I’ve written before about how my childhood admiration for Derek Jeter made me a disciple of the church of the closed batting stance. So obviously I harbored an intense dislike for Batista, whose posture in the batter’s box seemed entirely risible to me. And because I was wondering why in the heck anyone would debase himself by hitting like that, I always remembered Batista’s explanation: It helped him see the ball better.

Seeing as how Rice plays for the Yankees, and this is a highly noticeable change in technique, he’s been asked about the new stance before. His explanation: “[I] felt like it gave me a little bit more of an ability to see the baseball.”

Truly, there is nothing new under the sun.

Anyway, let’s see if Ivy League Tony Batista is actually seeing the ball better.

| Season | wRC+ | BB% | K% | Swing% | O-Swing% | Z-Swing% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 Triple-A | 175 | 18.1 | 18.8 | 40.7 | 20.6 | 62.3 |

| 2024 MLB | 73 | 11.2 | 27.0 | 26.0 | 19.9 | 71.9 |

| 2025 MLB | 160 | 11.4 | 25.2 | 42.7 | 23.1 | 61.0 |

Rice crushed high-minors pitching last year, hitting a combined .273/.400/.567 in 79 games across Double-A and Triple-A. Older power hitters with good bat speed are going to do that, and when a prospect like Rice comes to the majors, question no. 1 is usually: How is he going to adapt to pitchers who can spin the ball, command the ball, and do both at the same time?

Even the most demanding evaluator would give a rookie some grace while he figures things out. But Rice wasn’t chasing wildly outside the zone last year. He wasn’t striking out at a ridiculous rate; in fact, he was making more contact, especially within the strike zone, than he did in the minors.

Rice had two big problems last year. First is what looks to me like apocalyptically bad batted-ball luck. In 178 plate appearances as a rookie, Rice posted a .186 BABIP, and a .269 wOBA against an xwOBA of .340. Even notwithstanding the stance change, Rice fixed a lot of his problems by making nice with the malevolent spirit whose grave he walked over every morning on the way to the park last year.

Problem no. 2: As a rookie, Rice swung at more than 70% of the pitches he saw within the strike zone. Out of context, that’s not wacky aggressive or anything; plenty of really good hitters live in the high 70s in Z-Swing%. But in the minors, Rice was in the low 60s. In other words, he went from the bottom quartile for Z-Swing% to the top quartile, and I think it messed him up a little.

In Little League, you get taught to defend the strike zone. In the pros, you have to get your money’s worth out of each swing. Runs are scored, games and championships are won, and million-dollar contracts are earned not just by making contact, but by making hard contact. Which is not what you’ll get if you’re playing tennis with every backdoor sinker that comes near the plate.

Last year, Rice’s average swing speed was 71.4 mph, which was 243rd out of 503 hitters who took 100 or more swings. This year, it’s 74.6 mph, which is 30th out of 230 hitters who qualified for Baseball Savant’s leaderboard. Or, if you want some more useful context, it’s one spot ahead of Bryce Harper, one of the poster boys for selective aggression.

Here’s how Rice did on pitches in the strike zone last year, compared to this year.

| Year | BA | OBP | SLG | wOBA | xwOBA | Whiff% | Bat Speed | Swing% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | .190 | .185 | .405 | .245 | .331 | 17.6 | 71.7 | 72.9 |

| 2025 | .321 | .321 | .705 | .438 | .444 | 16.4 | 74.8 | 62.4 |

Rice put on a little weight over the offseason, so some of the increased bat speed is probably attributable to added strength. But he’s made enormous gains in terms of identifying his pitch and letting it rip.

It’s a welcome development for the Yankees. Rice has started 28 games this year, 23 of them in the first three spots in the batting order. Rice has scored 22 runs this year, of which 13 have either come on his own home run or on an RBI provided by Judge. As the season has gone on, and manager Aaron Boone has put more faith in the resurgent Trent Grisham (speaking of wild comeback stories), Rice has started hitting behind Judge, who’s moved up to second in the order.

Last year, Judge drove in 144 runs, the highest total in a major league season since 2008. That was the result not only of his own ridiculous power output, but of hitting behind a left-handed two-hole hitter with a .419 OBP. Even before Yankee pitchers started blowing out their arms two or three at a time, it was reasonable to wonder how the Yankees would get on if Judge didn’t have Juan Soto to drive in anymore.

I am by no means saying that Rice is on Soto’s level now, or that he could get on Soto’s level in the future. There is no replacing Soto.

But Rice has filled more of that hole than anyone would’ve expected after last season. He’s not a superstar hiding in plain sight, but he’s carried enough of the load that Judge can handle the rest.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

I know this is pulling a stat from another site, but it’s interesting that Rice’s SEAGER was in the 88th percentile last year and only 45th this year. A lot of the positives seem to come from hitting the ball much harder as the article says.