I Got It! I Got It! I…: When Infield Flies Go Bad

While a strikeout is always nice, a pop up is typically also a great outcome for a pitcher. In fact, FanGraphs treats infield fly balls and strikeouts as equivalent when it comes to calculating FIP-based WAR. If you want to read more about it, our Glossary has a good overview, and this Dave Cameron article is particularly useful. As Dave puts it, “infield flies are, for all practical purposes, the same as a strikeout.”

That logic makes perfect sense, and that’s why infield fly balls are baked into WAR calculations with the same value as strikeouts today. By my calculations (necessarily a bit inexact as Baseball Savant categorizes balls in play somewhat differently), a measly 36 of the 3,866 infield fly balls this year have turned into base hits, mostly on flukes like this:

Justice was served on this play, and you could even debate the word “infield” since it landed on the outfield grass, but you get the general idea: short of a weird shift, very few infield fly balls turn into hits.

But just because few of them become hits doesn’t mean no one’s getting on base. Cameron again: “Sure, maybe you or I wouldn’t turn every IFFB into an out, but for players selected at the major league level, there is no real differentiation in their ability to catch a pop fly.”

Sure, major league infielders, even the very worst of them, have preternatural hand-eye coordination and have spent thousands of hours of their lives catching baseballs. By their very nature, infield pop ups give fielders a long time to react. That ball is in the air for three, four, even five seconds. It’s one of the easiest plays you’ll ever get as a defender.

That’s all true, and yet infielders have dropped 38 pop ups this year. That simple play, baseball’s version of a wide open layup, isn’t always converted into an out. To be fair, six of them hardly count as being infield fly balls — this Starlin Castro drop should probably have been played by an outfielder, for example:

That still leaves 32 plays in which the pitcher got one of the best possible outcomes and got a baserunner for his troubles. Obviously, the fielders are to blame somewhat in these situations. But how much are they to blame? Let’s take a look at a few different kinds of infield fly balls that didn’t go as the defense planned.

A Lot of Ground to Cover

What is Pete Alonso supposed to do here?

He ran right to the spot, but this pushes the boundaries of a routine fly ball. It’s not really in the infield, though it’s an infielder’s play. He had time to square his shoulders to the infield, and he surely wishes he made the catch, but that’s not the easiest play Alonso will attempt all year, not by a long shot.

Wilmer Flores should have made this play, but at least he has an excuse:

That’s not a difficult play, but it’s not a gimme either. Pulled to second base by a shift, Flores has to hustle to get to the right spot, robbed of the normal time to line up the ball and take a few steps to re-center. Naturally, he looked sheepish after the play, but he’s not close to being the worst offender here today.

Lost It in the Lights

Sometimes baseball is played at night. All that time to watch the ball in the air does you no good if all you can see is high beams:

Halfway through the play, you can see Jung Ho Kang lose sight of the ball and take a look over towards second hoping someone else has a read on it. Maybe there was a bit of miscommunication involved, even. Either way, when Kang looks up for the ball, he simply picks it up too late. That’s not a failure as a fielder — it’s an unfortunate fact of playing baseball when people want to watch it.

Too Much Time to Think

Those first two categories aren’t stellar defensive plays, but they aren’t complete embarrassments either. These next few… these next few are rough. Ian Kinsler has time to incorporate a small business in shallow center field before catching this ball:

He sees it all the way in, has his glove in catching position, and he simply whiffs on it. Rarely does a major leaguer look like me playing softball, but this is an exception. Major league infielders are almost always, when they make a play, moving quickly by instinct. Spend nearly seven seconds standing still and waiting to act, as Kinsler did, and there’s too much time for the mind to go haywire, to wonder whether Luis Urías is coming for your playing time or whether your stove was on when you left for the ballpark that day.

Tim Anderson isn’t standing still the whole time, but he could have been. He first misjudged the play, then misjudged his adjustment, and finally had to make a sudden lunge despite having had all day to get to the right spot:

If Anderson had gone straight back at the start of the play, he would have been in Kinsler mode, waiting a long time for the ball to arrive. Instead, he managed to both have too much time to wait and not enough time to act.

Pitcher Gets Involved

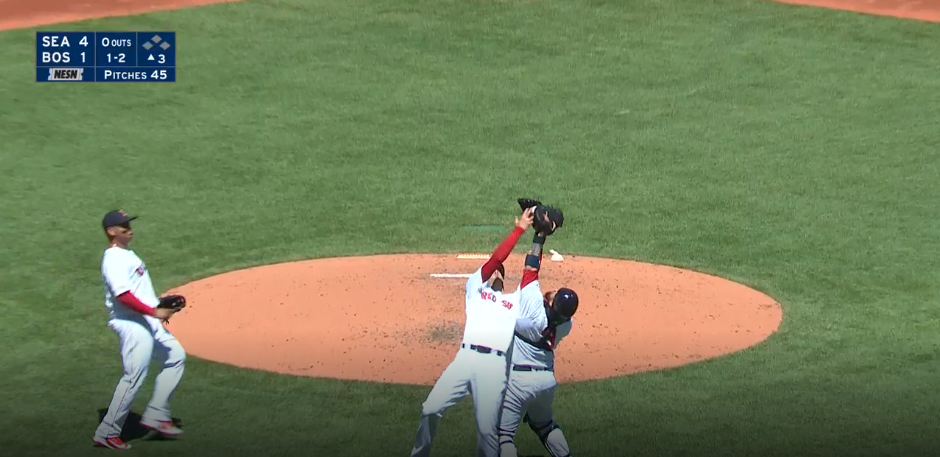

Pitchers don’t catch fly balls. It’s a tradition as old as time, and it’s not without merit. Rick Porcello probably didn’t need to enter the picture here:

There’s no question who should get be in charge here. Porcello had a good look at it, but that’s Sandy León’s ball from the start. León realizes too late that Porcello is getting involved — basically when Porcello’s glove hits the ball before his own:

From there, it’s all over. Rafael Devers can only look on, secure in the fact that he’s not the one dropping a pop up. The joke’s on him, though, because only a month later, he got in on the act:

Ah, fate.

Pitcher Doesn’t Get Involved

Pitchers don’t catch fly balls. It’s a tradition as old as time, but one that sometimes has its drawbacks. Roenis Elías doesn’t want to get into the fray here, trusting Tim Beckham to do the heavy lifting:

He gives a half-hearted chase, but Beckham is supposed to be the captain here. The only problem is, Beckham is a shortstop by trade and has no experience with the angles involved in playing first base. He veers off into foul territory, leaving Elías on an island, and it ends predictably. With pitchers, you just can’t win sometimes.

Miscommunication Galore

Tons of these dropped infield fly balls involve some degree of miscommunication. Two players aren’t quite sure who’s going for it, and the indecision ends up costing them. Some plays, though, go above and beyond:

Why — why would that be the third baseman’s ball? Paul DeJong certainly doesn’t think it is, and he’s tracking it all the way. Gyorko was rusty, having not played much at all this year, but he would have served the team better on that play by staying on the bench.

That’s nothing, though, compared to this doozy:

There’s a lot to unpack here. Cheslor Cuthbert is wearing shades, but they must not be working, because he has his glove up covering his eyes the entire time. He’s not looking home at all. Martín Maldonado, meanwhile, is somehow facing towards the first-base dugout while backing into the field of play. That’s not going to end well very often. As an added cherry on top, Cuthbert and Maldonado form a wall to keep Brad Keller from quickly getting to the dropped ball, allowing Teoscar Hernández to take second:

Ladies and gentlemen, your 2019 Royals.

Repeat Performance

Maldonado has experience with infield fly ball errors. He reached on one early in the season:

As the genre goes, this one isn’t terrible. Robertson lost the ball in the lights for a bit and didn’t do a good job recovering. He simply wasn’t ready for the ball to land. As the above examples show, this is bound to happen from time to time.

Yonny Chirinos had a rough time after this error. He gave up a walk, a triple, and a sacrifice fly before escaping the inning. Still, things could have been worse; the Rays won the game. Surely, though, Chirinos was frustrated by that one.

Then it happened again. Two months later, Chirinos got another infield fly, something he’s done a team-leading 15 times this year. This one was an even easier location. It’s in this article though, so you know what happened next:

Two in a year! That’s rough. My favorite part of the gif is Chirinos pointing, then lowering his finger uncertainly as he starts to realize what might happen. His point is useless and vestigial, something all pitchers do but none gain much advantage from. Seeing it wither as he realizes another drop is coming, or at least a near miss, is heart-wrenching, in a miniature way.

Chirinos couldn’t catch a break with these errors. Gio Urshela hit a home run two batters later, and the undeserved runner scored again. Sometimes baseball can feel unfair.

…

Dave Cameron is probably right. There’s no real differentiation in how good players are at catching infield fly balls. It’s a simple act, one every single major leaguer is capable of. It’s also a reminder that sometimes life is hard, and if you repeat the same simple task enough times, you’re bound to mess it up. I needed two tries to tie my shoes this morning. That’s essentially what happened to almost all of these players — they just happened to goof up their easy task in front of thousands of fans instead of at home by themselves.

I feel bad for them — that could have happened to literally anyone. At the same time, I’m delighted. Who doesn’t want to see Royals collide for seemingly no reason? Who doesn’t want to see Ian Kinsler write a novella in center field and then forget to catch a baseball? Baseball isn’t life or death, and because of that, I feel totally fine enjoying some talented athletes do some incredibly unathletic, clumsy things.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

I am mildly curious (not curious enough to actually figure it out) about how many runners reach on strikeouts per year.

81 so far this season, 113 last season, and 1078 times overall this decade.