In Appreciation of Blake Snell

Maybe you’ve heard — Blake Snell pitched a nifty five-plus innings two nights ago. The decision to pull him or leave him in has been hashed, rehashed, diced, A-Rod’ed, and generally poked and prodded like a murder victim in an episode of CSI. If you want my opinion on it, I would have kept Snell in, though I don’t think that was in any way the determining factor in the game.

That’s not why I’m writing today, though. Any honest analysis of that decision is going to come down to a minuscule edge. Use one good pitcher, or use another good pitcher? It doesn’t matter much — the players on the field determine the game, not the manager, even if you think the decision was clearly one way or the other. Instead, let’s appreciate not what Blake Snell could have done if he stayed in, but what he did do when he was in the game.

Snell threw 73 pitches on Tuesday night. He generated a whopping 16 swinging strikes, a 21.9% swinging strike rate. That was his second-highest mark of the year, behind a September 29 start against the Blue Jays. That might not sound impressive, but the Dodgers are, well, the Dodgers. No other starter this year topped a 20% swinging strike rate against them; they simply aren’t the kind of team that swings and misses.

Against Snell, they were. He did it with every pitch. His fastball was explosive, avoiding bat after bat in the zone:

The Dodgers swung at 15 of Snell’s fastballs and came up empty on eight. One other pitcher all year, regular season and postseason combined, enticed 15 or more swings at fastballs and got a higher whiff rate — Julio Urías in Game 4 of the World Series, believe it or not.

Snell’s curveball and slider also baffled the Los Angeles lineup. The raw numbers aren’t quite the outliers that his fastball created, because breaking pitches induce more whiffs, but they were still overpowering: four whiffs on his slider and three on his fastball, good for 26.7% and 20% swinging strike rates, respectively. You want a visual? You probably want a visual. Here’s the slider turning Cody Bellinger into a pile of jelly:

Gross, right? That’s what happens when you have to think about the soul-stealing fastball, and it’s not as though picking up on a curveball is easy either:

The Dodgers were simply overmatched on their swings. Bellinger looked roughly the same whether he was swinging at a Snell heater or a bee:

If that’s all there was to say about Snell’s start, it would be impressive. On the biggest possible stage, against a fearsome opponent, Snell was as unhittable as anyone had been all year. That undersells his sheer dominance, though. Called strikes help a pitcher’s cause just as much as whiffs, and Snell excelled there as well. When he wasn’t blowing the Dodgers away, he was freezing them in place on his way to 13 called strikes. That 18% called strike rate would have been his fifth-best of the year.

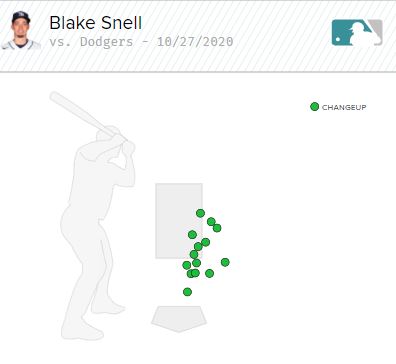

You’ve already seen the whiffs, but the called strikes showed a precision Snell has rarely achieved in his major league career. He dotted the corners, hitting the edges of the zone when he needed a strike. He was particularly lethal on the outside corner to righties, where he caught them looking seven times. Four of those came on his changeup, which he located exactly where he wanted it: on the outside part of the plate and away, where they could either live with the umpire’s call or take a feeble swing:

Combine the called and swinging strikes, and you get a statistic called CSW%. Snell checked in at 40% Tuesday night — in other words, 40% of his pitches he threw ended up as strikes. Not fouls, which can differ in type from the 400 foot just-missed-it blast to a jam shot down the third base line, but strikes — pure, unfiltered strikes.

As you can probably guess from my extended and breathless description, 40% is excellent. It’s Snell’s best mark of the season, for one. It’s in the top 2% of all starts this year; the best mark was Lucas Giolito’s 47.5% in his August 25 no-hitter. It’s also the best mark against the Dodgers all year, narrowly ahead of Zac Gallen’s July 31 gem.

Whiffs and called strikes aren’t all there is in baseball. Sometimes, despite your best efforts as a pitcher, the other team hits the ball. Snell faced 18 batters and struck nine out, which means he allowed nine balls in play.

Of those nine, one was hit more than 95 mph, the “hard-hit” cutoff. Chris Taylor laced a line drive into left at 105.4 mph, a clean single that was one of the two hits the Dodgers managed all night. The others were some mixture of medium-hit line drives and truly poor contact. The only other hit against Snell was this Austin Barnes single in the sixth, another clean single that came nowhere near threatening extra bases:

Two singles is a meager offensive output, but it’s pretty much all the Dodgers deserved. They couldn’t do anything with Snell’s pitches; Mookie Betts, one of the great contact hitters of our era, managed a single foul ball when he offered at Snell’s pitches. His other three swings got only air.

To be clear, none of this means that Snell was going to keep up this level of performance the rest of the game. Research employing various methods has found no evidence that a pitcher who cruised the first two times through the order was any better the third time through. There’s some evidence that things might be slightly different in the playoffs, as Tom Tango wrote yesterday, but again, who cares? There’s a world where Snell shoved for another three innings and the Rays won. There’s a world where he got Game 2’ed — he was cruising through four no-hit innings then, but gave up a walk, then a homer, then another walk, then a single, and all of the sudden the game went from over to contested.

Those worlds didn’t happen, and I don’t care about them. I care about this one, where Blake Snell was downright magnificent. For 5.1 tremendous innings, he looked like a man playing a video game on easy mode. The curves were nasty, the fastballs hellacious, and the Dodgers stood a better chance of making contact with an insect than with the baseball. That’s Snell as he was on Tuesday. Anything else is just conjecture.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

I was just blown away by what he was doing. That stuff looked incredibly nasty.

I question whether Blake Snell is really consistent enough to be that league ace everyone thought he was back in 2018–he was good, but he benefitted a lot from the Rays magical defense back then (and still does). But holy hell did he turn it on for that game. It was just strikeout city. Between that and Kershaw’s gems, there was some really great pitching going on this series.

Yeah you could really believe those teams had top 3 pitching staffs in MLB in that series, and the Rays really did a herculean effort to keep it under control as long as they did. It felt like you could really tell that the Rays offense was the one unit that wasn’t elite – Rays P vs Dodgers O was a real strength vs strength matchup, but Rays O vs Dodgers P was just too unbalanced over the balance of the series.

I’m not sure if this came up in the other article about Snell (I haven’t read it yet), but there was a great twitter analysis I saw that is kind of boggling:

https://twitter.com/ckurcon/status/1321483776141205506

If you dont want to click, the summary is that in starts as similar as possible to Snell’s over the last 4 seasons (at least 9Ks, 2 or less baserunners thru 5) over the last season, which is 202 games by exclusively elite pitchers (Verlander, Scherzer, etc), they allowed a 0.56 ERA through the first 5 innings, and then allowed a 3.86 ERA in exactly the 6th inning. A foible of that kind of outing is that it creates a situation similar to the first inning of a game: The top of the order is guaranteed to bat with a full set of outs to work with, becuase there’s been so few baserunners. Consequently, you get pretty high offense.

It’s kind of boggling to think that it’s a statistical reality in MLB that the greatest pitchers in the game, in no hitter/perfect game type scenarios, are still more likely to allow a run than an elite reliever the 3rd time through the lineup. It’s the kind of thing that seems like it shouldn’t be true, and that we shouldn’t want to be true. But it is.

I am reminded of how everyone was pointing back to the 19 Nats in nostalgia for those long starter outings, but it kind of ignores how the 19 Nats had a bullpen so awful that that was an optimal strategy for them. I’d be interested in analyzing whether it’s possible that moving all series to the model used this year – the no-offdays setup – would actually help, because it taxed the bullpens so deeply between the lack of rest and the forced use of weaker starting pitchers in some games, that it kind of made getting length from your best pitchers valuable in the LDS and LCS rounds.

In the regular season, you can only operate like the Rays if you have a bullpen like the Rays, and most teams don’t, so they need to ask starters for length sometimes. In the postseason, with offdays, you can avoid that. It’s interesting to think about how much the Rays’ bullpen was taxed by those two earlier series, and to what degree that influenced both Anderson and Fairbanks allowing a good number of runs and baserunners to the Dodgers. How much better would those guys have been with rest days in the previous rounds? I bet the answer is ‘some’.