JAWS and the 2020 Hall of Fame Ballot: Billy Wagner

The following article is part of Jay Jaffe’s ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2020 Hall of Fame ballot. Originally written for the 2016 election at SI.com, it has been updated to reflect recent voting results as well as additional research. For a detailed introduction to this year’s ballot, and other candidates in the series, use the tool above; an introduction to JAWS can be found here. For a tentative schedule and a chance to fill out a Hall of Fame ballot for our crowdsourcing project, see here. All WAR figures refer to the Baseball-Reference version unless otherwise indicated.

Billy Wagner was the ultimate underdog. Undersized and from both a broken home and an impoverished rural background, he channeled his frustrations into throwing incredibly hard — with his left hand, despite being a natural righty, for he broke his right arm twice as a child. Scouts overlooked him because he wasn’t anywhere close to six feet tall, but they couldn’t disregard his dominance over collegiate hitters using a mid-90s fastball. The Astros made him a first-round pick, and once he was converted to a relief role, his velocity went even higher.

Thanks to outstanding lower-body strength, coordination, and extraordinary range of motion, the 5-foot-10 Wagner was able to reach 100 mph with consistency — 159 times in 2003, according to The Bill James Handbook. Using a pitch learned from teammate Brad Lidge, he kept blowing the ball by hitters into his late 30s to such an extent that he owns the record for the highest strikeout rate of any pitcher with at least 800 innings. He was still dominant when he walked away from the game following the 2010 season, fresh off posting a career-best ERA.

Lacking the longevity of Mariano Rivera or Trevor Hoffman, Wagner never set any saves records or even led his league once, and his innings total is well below those of every enshrined reliever. Hoffman’s status as the former all-time saves leader helped him get elected in 2018, but Wagner, who created similar value in his career, has major hurdles to surmount given that he’s maxed out at 16.7% in four years on the ballot, that after receiving a 5.6% jump in this past cycle. Nonetheless, his advantages over Hoffman — and virtually every other reliever in history when it comes to rate stats — provide a compelling reason to study his career more closely. Given how far he’s come, who wants to bet against Billy Wags?

| Pitcher | Career | Peak | JAWS | WPA | WPA/LI | IP | SV | ERA | ERA+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Billy Wagner | 27.7 | 19.8 | 23.7 | 29.1 | 17.9 | 903 | 422 | 2.31 | 187 |

| Avg HOF RP | 39.1 | 26.0 | 32.5 | 30.1 | 20.0 |

Wagner was born in Marion, Virginia, on July 25, 1971, into circumstances — as documented in a September 20, 1999 Sports Illustrated profile by Michael Bamberger — that were hardly idyllic. Father William “Hotsey” Wagner, an all-county pitcher, married his 16-year-old bride, Yvonne Hall, on the day he graduated high school. Billy was born 13 months after they wed; two weeks later, Hotsey left for Saigon, where he spent nine months monitoring the urinalyses of U.S. soldiers about to return home from the Vietnam War. His marriage collapsed in 1976, after he returned home. Billy and his younger sister bounced around in the care of his divorced (and remarried, and re-divorced) parents and both sets of grandparents. Poverty was a constant; food stamps were an embarrassment; “[a] few crackers with peanut butter and a glass of water” was a typical breakfast.

While playing football at age seven, Wagner broke his right (throwing) arm when a friend fell on it; six weeks later, just after the cast was removed, Wagner broke it again. During this time, he learned to throw left-handed, turning his baseball glove inside out and channeling his anger at his instability and grim surroundings into throwing a ball at the side of his maternal grandparents’ house, doing it so hard that pieces of aluminum siding fell off. Finally, just before he turned 15, he went to live with Jack and Sally Lamie, his uncle and aunt, in Tannersville, 19 miles away. By that point, Billy had fallen a year behind in school due to his unstable home situation, but once coaches and administrators at Tazewell High School (the closest high school, an hour away) agreed that his throwing was a danger to his middle-school peers, they “socially promoted” him into high school.

Though he grew to just 5-foot-5 and 135 pounds in high school, Wagner starred as both a center fielder and pitcher whose fastball could reach 86 mph. As a senior in 1990, he hit .451, stole 23 bases, and struck out 116 in 46 innings with a 1.52 ERA. Scouts were put off by his size, so he followed cousin Jeff Lamie to Ferrum College, a Division III school, with the intention of playing football — until the coach saw him throw a baseball. At Ferrum, Wagner grew to 5-foot-9, gained 40 pounds, and boosted his velocity to 93 mph. As a sophomore in 1992, he allowed nine hits in 51 innings and set an NCAA record with 19.1 strikeouts per nine. While dominating the collegiate Cape Cod League, he struck out the side in the league’s All-Star game without allowing a foul ball. The Astros chose him with the 12th pick in the 1993 draft.

By now 5-foot-10 and 170 pounds, Wagner began his professional career as a starter, battling control issues but whiffing more than a batter per inning at every stop and making Baseball America’s Top 100 Prospects list in 1994 (78th), 1995 (17th), and 1996 (14th). In 1995, he posted a 2.89 ERA in hitter-friendly Double-A and Triple-A leagues, with 9.7 strikeouts per nine in 146.1 innings. All the more impressive was that his performance came amid tragedy, as his wife’s father — who had emerged as a father figure in Wagner’s life — and stepmother were brutally murdered in May, just days after Wagner had been added to the Astros’ 40-man roster in anticipation of a late-season call-up.

Wagner made his major league debut on September 13, 1995 in Shea Stadium; mustering a fastball near 100 mph, he retired the Mets’ Rico Brogna on a fly ball before being lifted for a pinch-hitter by Astros manager Terry Collins. After 12 starts for Triple-A Tucson in 1996, the fire-balling Wagner, 24, joined the Astros’ bullpen in early June and supplanted the injured Todd Jones as the team’s closer after the All-Star break. He converted nine saves in 13 chances, finishing the year with a 2.44 ERA and 11.7 strikeouts per nine (but 5.2 walks) in 51.2 innings. The Astros carried a two-and-a-half game division lead into September, but a 4–16 tailspin to start the month lost them the division and ultimately cost Collins his job.

Under new manager Larry Dierker and powered by the “Killer B’s” — Jeff Bagwell and Craig Biggio — the Astros made the playoffs in each of the next three seasons, with Wagner emerging as one of the game’s most dominant closers. He saved 23 games with a 2.85 ERA and 14.4 strikeouts per nine in 1997, setting a record for a pitcher with at least 50 innings. Despite missing more than three weeks in 1998 after taking a Kelly Stinnett line drive off his head, he topped that strikeout rate in each of the next two seasons and trimmed both his walk rate and ERA. In 1999, he whiffed 14.9 per nine and walked 2.8 en route to a 1.57 ERA with 39 saves in 74.2 innings. Not only did Wagner make his first All-Star team, but he also tied teammate Jose Lima for fourth in a particularly Houston-heavy Cy Young vote; ex-Astro Randy Johnson won, and Mike Hampton finished second. Wagner’s 3.8 WAR led all National League relievers and nearly topped the 3.9 he had accumulated in the previous three seasons.

It was that September when Bamberger caught up with “the Astros’ smaller-than-life closer” who “would tip the scales at his listed weight of 180 pounds only after a third helping of grits,” exploring his difficult past in an attempt to find out, “Where does he get his heat?”

He throws fastball after fastball, one four-seamer after another, all in the A to A-plus range. The movement on his pitches is wicked. Batters speak of heaters that start at their heads and finish at the knees, on the outside corner of the plate. On Wagner you can guess fastball. (He throws only occasional sliders and changeups.) What you can’t do is hit it.

…It is true that Wagner has superb mechanics, which is amazing when you consider that he is a natural righthander … It is also true that he drives off the rubber as well as any pitcher since Tom Seaver; his legs are thick and heavy for a man of his otherwise ordinary physique. It is true that he has a remarkable ability to throw first-pitch strikes. But those facts alone do not begin to answer the question.

In February 1999, Wagner had signed a three-year, $10.1 million extension, covering his arbitration years. For as strong as his 1999 was, his 2000 was a near-total loss: Wagner struggled with his control in 27.2 innings before admitting he had been throwing in pain and undergoing season-ending surgery to repair a torn flexor tendon and remove scar tissue. With their bullpen a garbage fire, the Astros sank to 72–90, but both Wagner and the team rebounded in 2001. Wagner made his second All-Star team, saved 39 games, whiffed 11.3 per nine, and finished with 2.4 WAR; the Astros won 93 games and their fourth NL Central title in five years. Alas, they were again ousted in the first round by the Braves, the team that had done so in 1997 and ’99 as well.

By both WAR and ERA, Wagner’s performance continued to improve in 2002 and ’03. In the latter season — his third All-Star campaign — he set career highs with 86 innings and 44 saves en route to a 1.78 ERA, 11.0 strikeouts per nine, and 3.4 WAR, the last of which edged John Smoltz for the lead among NL relievers. On June 13, 2003, Wagner helped to make baseball history when he closed out a combined no-hitter of six pitchers against the Yankees in the Bronx — the first time New York had been no-hit since 1958. Two pitches into the second inning, starter Roy Oswalt had to depart due to a groin injury; relievers Pete Munro, Kirk Saarloos, Lidge, and Octavio Dotel carried the baton to Wagner, who struck out Jorge Posada and Bubba Trammell, then covered first base on Hideki Matsui’s game-ending groundout.

After missing the playoffs in 2002, the Astros battled with the Cubs for the NL Central title in 2003, but a 3–6 record over the final nine games cost them a one-and-a-half game lead. While Wagner took one of those losses, it was only the second time over his final 36 appearances that he allowed a run. After the season, he criticized owner Drayton McLane for the team’s failure to increase payroll to augment their rotation. “It’s going to be a tape job,” he said after the team’s final game, looking to next season. “It’s not like we’re going out there and getting any marquee pitchers.”

Wagner would be proven quite wrong, but he had punched his ticket out of town. Owed $8 million for 2004 with a $9 million option for 2005, he was traded to Philadelphia on November 3 for a trio of pitchers (Ezequiel Astacio, Taylor Buchholz, and Brandon Duckworth) who combined to deliver -3.4 WAR as Astros. Their sorry production was more than offset by Houston’s marquee free-agent pitchers: Roger Clemens and Andy Pettitte. Though the latter was limited to 15 starts in 2004 due to elbow surgery, the former won his seventh Cy Young award. The revamped Astros — who also added Carlos Beltran for the 2004 stretch run — reached the NLCS in 2004 and then the World Series in ’05. “I just wish he’d done this when we were a game out last season,” said Wagner of McLane’s spending.

Though he joined a team that was beginning to assemble the roster that would dominate the NL East from 2007-11, Wagner’s two years in Philadelphia were less than fulfilling. Groin and rotator cuff strains cost him two-and-a-half months in 2004, limiting him to 48.1 innings. He rebounded with another All-Star season in 2005 (1.51 ERA, 38 saves, 2.7 WAR), but his mouth continued to make bigger headlines. Amid a 4–12 July skid, he criticized the team’s intensity, saying that the Phillies quit when they fell behind and that “we ain’t got a chance to get there right now,” in reference to the postseason. While the Phillies finished with 88 wins under new manager Charlie Manuel, they fell one game short of the wild card and two short of the division title. Wagner spent the last third of the season in silence after receiving no support in a players-only meeting, then blasted his ex-teammates from afar after departing. Years later, he lamented, “I learned a lot about criticism and how not to be a leader when I was traded … I began to turn into someone I didn’t want to be.”

A free agent for the first time, the 34-year-old Wagner landed a four-year, $43 million deal with the Mets and sparked an inter-borough controversy: his entry song, Metallica’s “Enter Sandman,” was already in use by the Yankees’ Mariano Rivera, though Wagner’s 1996 adoption predated Rivera by three years. The song got a workout in Queens: Wagner saved 40 of the Mets’ 97 wins as they claimed their first NL East title in 20 years. Accompanied by a typically low 2.24 ERA, Wagner’s save total ranked second in the league, the highest he would ever finish, and his 11.7 strikeouts per nine was his highest mark since 1999. He notched the first three saves of his postseason career as the Mets downed the Dodgers and won the NLCS opener against the Cardinals, but he took the loss in Game 2 by allowing three ninth-inning runs, then gave up two runs while protecting a 4–0 ninth-inning lead in Game 6. In Game 7, manager Willie Randolph left setup man Aaron Heilman in for his second inning of work in the ninth inning of a tie game; Wagner could only watch as Heilman served up a decisive two-run homer to Yadier Molina.

That was as close as Wagner ever got to a World Series. Though he pitched very well for most of 2007, saving 26 of his first 27 chances with a 1.28 ERA, he posted a 6.91 ERA from August 21 onward, a span of 14 appearances. That Mets team gained infamy for blowing a seven-game lead with 17 games to go, losing out on a playoff spot on the season’s final day, but Wagner’s only blown save in that span came in a New York win. The team wound up outside the playoff picture on the final day in 2008 as well, in part because Wagner’s August 2 forearm strain led to Tommy John surgery.

When the Mets signed Francisco Rodriguez to a three-year, $37 million deal that winter, the writing was on the wall for the rehabbing Wagner. After making two late August appearances for the team, he waved his no-trade clause and was dealt to the Red Sox, who in turn promised not to pick up his $8 million option for 2010, granting Wagner complete freedom in choosing where to pitch the following season. He was strong in 15 appearances for Boston, striking out 22 in just 13.2 innings for a team that won the Wild Card but was swept out of the first round by the Angels.

In December 2009, Wagner signed a one-year, $7 million deal with Atlanta, and at 38, he pitched as well as ever, posting a career-low 1.43 ERA and striking out 13.5 per nine (his highest rate since 1999) in 69.1 innings en route to 2.5 WAR for yet another Wild Card team that made a first-round exit. On June 25 against the Tigers, he struck out the side on 10 pitches and became the fifth pitcher to reach 400 saves in his career. On August 27, he struck out Giancarlo Stanton (then known as Mike) for his 1,170th career strikeout, surpassing Jesse Orosco for the record among left-handed relievers:

Despite triggering a vesting option for 2011, Wagner followed through with a decision announced in May: he would retire at season’s end to spend more time with his family. No pitcher has ever walked away from his career following a season of at least 50 innings with a lower ERA or a higher strikeout rate.

…

Wagner holds some other distinctions as well. Among pitchers with at least 800 innings, his strikeout rate — whether expressed as 11.9 per nine or as 33.2% of all batters faced— is the best in history by a comfortable margin. Yu Darvish’s 11.1 per nine and Chris Sale’s 30.7% are the next-closest marks, and with fewer than 620 innings under their belts, Aroldis Chapman (41.1%), Craig Kimbrel (41.1%), and Kenley Jansen (37.6%) are years away from overtaking him. At the 800-inning level, Wagner’s .187 opponent batting average is the lowest in history, 12 points lower than the next 20th- or 21st-century pitcher, Herb Score. Wagner’s 0.998 WHIP just edges Rivera’s 1.000 for second all-time behind dead-ball era hurler Addie Joss (0.968). Meanwhile, Rivera is the only post-1920 pitcher with a lower ERA (2.21) or higher ERA+ (205) than Wagner’s 2.31 and 187. Among that same group, Sandy Koufax is the only pitcher with a FIP lower than Wagner’s 2.73 (Clayton Kershaw climbed to 2.74 in 2019). Oh, and Wagner’s 422 saves are sixth on the all-time list behind Rivera (652), Hoffman (601), Lee Smith (478), Rodriguez (437), and John Franco (424).

Is that a Hall of Fame career? As I’ve laid out in connection to the cases of Smith and Rivera, with such a limited number of relievers in the Hall — the aforementioned pair, both elected last year, bring the total to eight — it’s difficult to say, particularly given the role’s evolution over the past half-century. Hoyt Wilhelm, Rollie Fingers, and Goose Gossage were all multi-inning firemen who racked up higher innings totals than the enshrined relievers who followed in their wake. Bruce Sutter worked multiple innings as well, though generally only when his team had a lead narrow enough to produce a save opportunity. Dennis Eckersley, who spent the first half of his career as a starter, became the model for the one-inning closer we know today. Even excluding Eckersley’s 3,285.2 innings, the other seven relievers elected averaged 1,496 innings, whereas Wagner threw only 903, well below even Hoffman’s 1,089.1 and Sutter’s 1,042. Where the majority of the saves of Wilhelm, Fingers, Gossage, and Sutter were longer than an inning, as were 27% of Eckersley’s, only 9% of Wagner’s were.

While one can certainly make the case that, based on rate stats, Wagner was more dominant than any of them, his shortfall of innings presents a problem when translating to a value measure such as WAR. That said, he was so much more dominant than Hoffman that the two are tied at 23.7 JAWS, with Hoffman’s slight edge in career WAR (28.0 to 27.7) offset by Wagner’s slight edge in peak (19.8 to 19.4). Either way, both are significantly below the standards at the position even if I exclude Eckersley. The other seven elected relievers averaged 35.8 career WAR, 23.6 peak WAR, and 30.1 JAWS. One can’t really justify Wagner’s inclusion in Cooperstown on the basis of those metrics.

That doesn’t mean it’s game over, though. While the version of WAR used in JAWS features an adjustment for leverage — the quantitatively greater impact on winning and losing that a reliever has at the end of the ballgame than a starter does earlier — to help account for the degree of difficulty, it’s not the only way to measure reliever value. Win Probability Added (WPA) is a context-sensitive measure that accounts for the incremental increase (or decrease) in chances of winning produced in each plate appearance given the inning, score, and base-out situation. For a reliever, a single-season WPA scales similarly to a single-season WAR, which is to say that it’s rare that one is worth more than three wins in a single year, by either measure. Wagner ranks a respectable seventh in WPA at 29.1, trailing the runaway leader Rivera (56.6) as well as Hoffman (34.2), Gossage (32.5), Eckersley (30.85), Wilhelm (30.84), and Joe Nathan (30.6), with Smith 15th (21.3), Sutter 28th (18.2), and Fingers 33rd (16.2). The average for the seven enshrinees is 29.1; Wagner is one win below that; he was 2.8 above when I checked in last year, between the elections of Smith and Rivera.

Another way to view reliever value along these lines is to adjust WPA using a pitcher’s average leverage index (aLI) for a stat variably called situational wins or context-neutral wins (referred to as WPA/LI). Here Wagner ranks fifth all-time. Putting WAR, WPA, and WPA/LI into a composite measure in an attempt to capture all this:

| Rk | Pitcher | WAR | WPA | WPA/LI | Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mariano Rivera+ | 56.2 | 56.6 | 33.6 | 48.8 |

| 2 | Dennis Eckersley+ | 62.0 | 30.8 | 25.7 | 39.5 |

| 3 | Hoyt Wilhelm+ | 46.8 | 30.8 | 27.0 | 34.9 |

| 4 | Rich Gossage+ | 41.2 | 32.5 | 14.9 | 29.5 |

| 5 | Trevor Hoffman+ | 27.9 | 34.2 | 19.3 | 27.1 |

| 6 | Billy Wagner | 27.7 | 29.1 | 17.9 | 24.9 |

| 7 | Joe Nathan | 26.7 | 30.6 | 15.7 | 24.3 |

| 8 | Tom Gordon | 34.9 | 21.3 | 14.6 | 23.6 |

| 9 | Jonathan Papelbon | 23.5 | 28.3 | 13.4 | 21.7 |

| 10 | Ellis Kinder | 28.8 | 23.6 | 11.6 | 21.3 |

| 11 | Lee Smith+ | 28.9 | 21.3 | 12.8 | 21.0 |

| 12 | Francisco Rodriguez | 23.9 | 24.4 | 14.7 | 21.0 |

| 13 | Stu Miller | 27.0 | 20.2 | 13.0 | 20.1 |

| 14 | Tom Henke | 22.9 | 21.3 | 14.0 | 19.4 |

| 15 | Dan Quisenberry | 24.7 | 20.7 | 12.4 | 19.3 |

| 16 | Rollie Fingers+ | 25.6 | 16.2 | 15.2 | 19.0 |

| 17 | Tug McGraw | 21.8 | 21.5 | 13.2 | 18.8 |

| 18 | Bobby Shantz | 34.6 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 18.3 |

| 19 | Firpo Marberry | 30.5 | 14.7 | 9.5 | 18.2 |

| 20 | Craig Kimbrel | 19.6 | 23.3 | 11.7 | 18.2 |

| 21 | John Hiller | 30.5 | 14.6 | 9.4 | 18.1 |

| 22 | Bruce Sutter+ | 24.1 | 18.2 | 11.9 | 18.1 |

| Hall avg w/Eck | 39.1 | 30.1 | 20.1 | 29.7 | |

| Hall avg w/o Eck | 35.8 | 30.0 | 19.2 | 28.3 |

Prior to the election of Rivera, Wagner was just 0.1 below the Hall average excluding Eckersley, and while his standing relative to that average has slipped, he’s the top reliever outside the Hall in that combined measure. I think that’s worth a lot in this context.

Meanwhile, it’s also worth mentioning Nate Silver’s Goose Egg stat, a WPA alternative introduced in April 2017 at FiveThirtyEight. A Goose Egg (named after Gossage, the all-time leader with 677) is a scoreless inning in a late, high-leverage situation (seventh inning or later, score tied or ahead by no more than two runs, no runs or inherited runners allowed to score, and so on); a pitcher can get more than one in a game. Wagner’s 421 Goose Eggs is only 19th all-time, well below the 584 averaged by the eight enshrinees (weighed down by Eckersley’s 352). However, with Broken Eggs (failures in Goose Egg situations) factored in and a replacement level baseline set (Goose Wins Above Replacement, or GWAR, not to be confused with these guys), Wagner’s 37.0 GWAR is fourth behind Rivera’s 54.6, Hoffman’s 43.7, and Gossage’s 39.4. With Wilhelm ninth (31.3), Sutter 12th (30.3), Smith 14th (28.9), Fingers 17th (25.3), and Eckesley 32nd (20.8), the eight enshrined average 34.3.

(Here it’s worth noting that Silver hasn’t revisited GWAR since late 2017, so it’s possible that Kimbrel, who was 40th on the list with 19.0 at the time, could have bypassed some of those enshrinees in the rankings; the same could be true for Chapman and Jansen, neither of whom cracked the leaderboard.)

All of those leverage-based measures provide a much stronger basis for voting for Wagner than JAWS. That goes doubly when taken alongside his other accomplishments and overlooking his unsightly 10.03 ERA in 11.2 postseason innings for teams that were generally in the midst of being steamrolled.

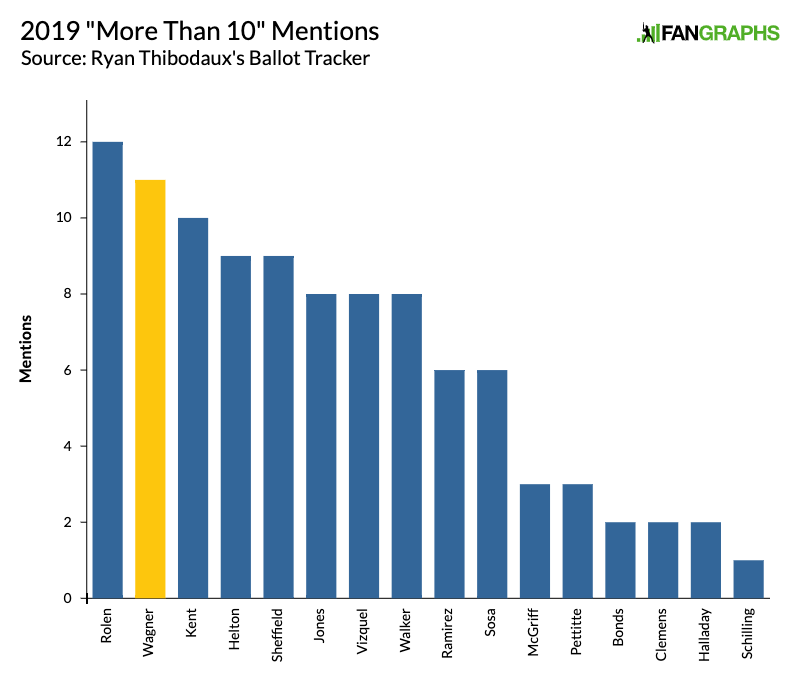

Nonetheless, Wagner faces an uphill battle to get to Cooperstown. Overshadowed by Hoffman when the two debuted in 2016, and lost in a sea of qualified candidates at other positions as well, he received just 10.5% of the vote in 2016, a lower debut percentage than any player elected by the writers since they returned to annual balloting in 1966. He more or less ran in place over the next two cycles, with successive shares of 10.2% and 11.1%, but last year, he gained 5.6%. What’s more, via Ryan Thibodaux’s Ballot Tracker, last year, 11 voters said that if they had room for more than 10 names, they would have included Wagner, suggesting they’re primed to add him for 2020.

I myself included Wagner on my virtual ballot for the first time, and will strongly consider doing so again this year as well as next, when I get an actual ballot. As I’ve said in each previous cycle, I’m not ready to close the door on Wagner. While JAWS guides my process, my concerns over its handling of relievers has led me to remain particularly open-minded in this area over the years, seeking alternative ways to evaluate them, and Wagner’s dominance in so many categories is difficult to ignore. He’s no Rivera, but he’s hardly out of place in a group that includes Hoffman, Smith, Fingers, and Sutter, and he might well complete the remainder of his run on the ballot as the best reliever outside the Hall of Fame. If that’s not worth a long look, I don’t know what is.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

I didn’t know he was a natural righthander. Makes you wonder if he could’ve pitched from both sides.

I bet alot of guys could do it if they actually tried there just isnt much incentive to try. They have coordination and athleticism to spare its probably just a matter of reps . I taught myself to throw with both hands mostly due to boredom at practices (weirdly i throw a football better from the left than my natural side) and I’m not even in the same universe as these guys lol.

I remember reading when he was with the Expos about how Pedro could reportedly throw in the high 80’s with his left hand and was mad he never got the chance to pitch both sides in a game.