Luke Weaver, Retooled and Reimagined

The book on Luke Weaver was written before he had played a game of professional baseball. Great changeup, good fastball, no third pitch. I mean “the book” metaphorically here, but I also mean it literally. Here’s Eric Longenhagen on Weaver before the 2017 season:

“Those who have questioned Weaver’s upside (myself included) did so because, in college, he lacked a good breaking ball. Weaver’s fringey curveball remains so today, but he’s a good athlete who has developed plus command and added an average cutter to his repertoire in pro ball.”

Cardinals fans got two years of data to back up that assessment — a scintillating 2017 (3.17 FIP, 28.6% K-rate) and a frustrating 2018 (4.45 FIP, fewer strikeouts and more walks) were worth a combined 2.7 WAR, but between underperforming his FIP and losing his rotation spot in the second half of 2018, Weaver felt like a surplus arm. The changeup and sneaky good fastball were as good as advertised, but batters consistently teed off on his curve. When Weaver and top catching prospect Carson Kelly were sent to the Diamondbacks in exchange for Paul Goldschmidt, it felt like a needed change of scenery for both of them.

If the book on Weaver was written while he was still in college, it’s a safe bet that he’s had time to read that book. He has worked towards developing a better breaking ball more or less every offseason of his pro career, and 2019 was no exception. This time, though, he had technological help. He bought a Rapsodo, a portable pitch-tracking camera, and used it to work on his curve. He took his cutter (or is it a slider?) out of mothballs, telling David Laurila he was picking up the hybrid pitch after years of being mainly fastball/change/curve.

Still, it’s one thing to decide you’re going to throw two new pitches and another entirely to actually follow through on that. Weaver’s work with the Rapsodo was eye-opening — it completely changed his curveball. His Cardinals-era curveball was essentially an Adam Wainwright starter kit — more horizontally sweeping than 12-6 plunging, almost like a slower slider. However, with little movement to speak of (20th percentile total break among starters), the pitch was simply too easy to track for hitters. The location on this pitch to Kevin Newman is dicey, and the lack of drop makes it a sitting duck.

Weaver’s curveball in 2019 is completely overhauled. The pitch’s horizontal break went from 50th percentile to the second-lowest sideways break in baseball. Its vertical drop went from 14th percentile to 33rd. This pitch to Max Muncy starts in a similar place to the pitch to Newman, but the extra three inches of drop give it a different look, doing just enough to make Muncy miss.

Changing the shape of his curveball, however, can’t hide the fact that the pitch is still his weakest. Though drop is a more efficient use of his curveball’s spin, the pitch still doesn’t break much in total. It’s more of a change of pace pitch than a hammer he can go to at will. The second piece of the puzzle has been throwing fewer curves, and throwing them early in counts to disrupt hitters’ timing rather than as an out pitch. Indeed, 60% of the curveballs Weaver has thrown this year have been on the first pitch of an at-bat, an opening gambit designed to disrupt hitters’ timing before he breaks out the changeup and fastball.

To get away with throwing so few curveballs, Weaver had to turn to his cutter. He’s throwing it 14.5% of the time this year, easily a career high, and using its similarity to his changeup (3 mph velocity difference, similar ride, eight inches of horizontal separation) to keep batters from sitting on one or the other. Cutters are notoriously difficult to analyze, or even classify — Weaver isn’t even sure if his is a slider or a cutter. Still, the early results of diversifying among breaking balls are solid, as the curveball is generating whiffs on 28% of swings (up from 19% last year) and the cutter a healthy 24% (13% in 2018).

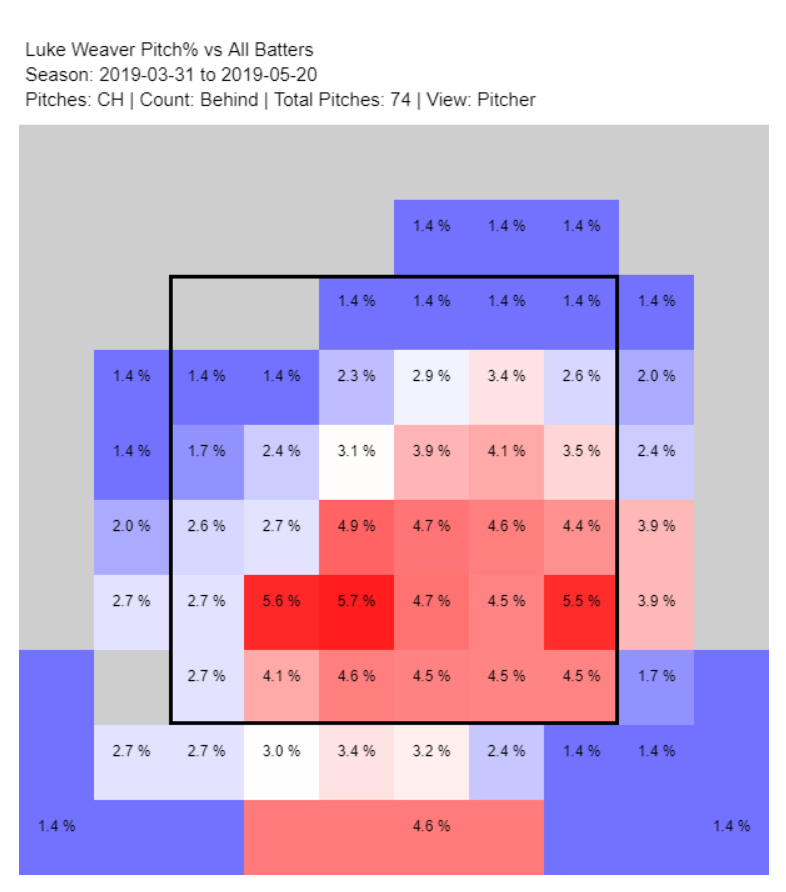

Efficiently mixing his two new breaking balls has unlocked the promise that Weaver has always shown. The changeup that carried him to the majors is as devastating as ever — batters can barely hit it (35% whiff rate), and even when they put the pitch in play, they’re generating an anemic .224 wOBA. Not only that, but it’s a Swiss Army Knife of a pitch. When Weaver is behind, he locates it for a strike, hitting the zone 60% of the time but still mostly avoiding the center of the plate.

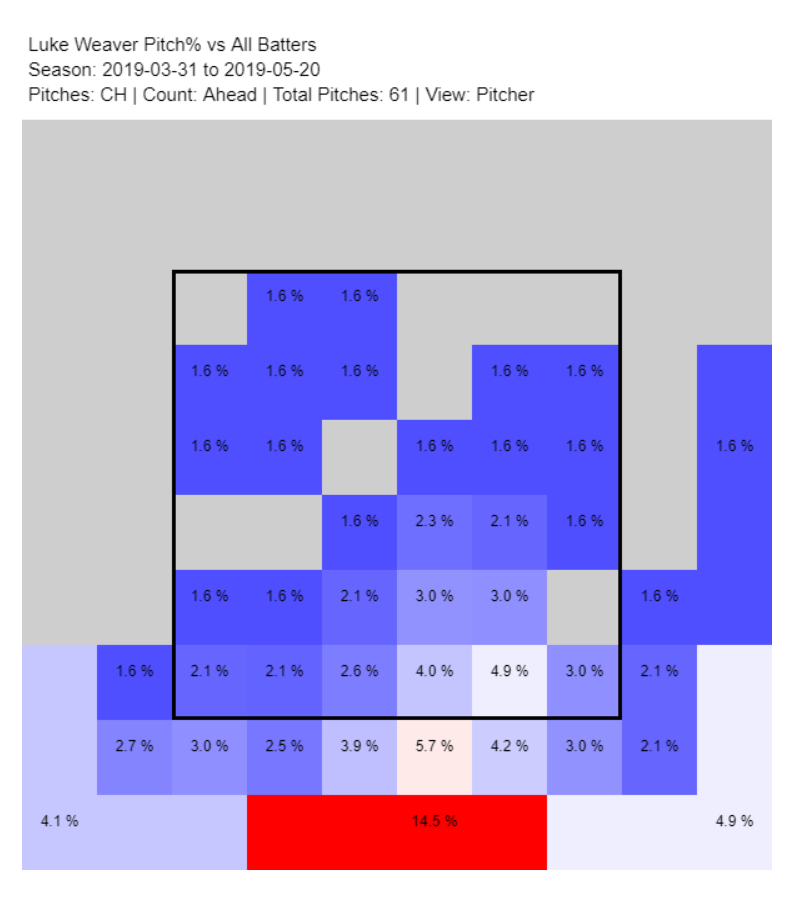

When he’s ahead in the count, the pitch turns into a swing-and-miss pitch, buried below the zone to induce bad defensive swings.

So far this year, this buried changeup has produced 16 swinging strikeouts and not a single one looking — batters simply can’t lay off the pitch when they’re protecting the plate with two strikes.

With that changeup disrupting batters’ timing and a mixture of breaking balls keeping them guessing, Weaver’s fastball has looked better this year. It’s a cookie-cutter rising fastball, an analytically inclined analyst’s dream that he locates up in the zone. The late life on the pitch, and the ever-present threat of a changeup, combine to miss plenty of bats (22% whiff rate, in the top third of starters’ four-seamers) despite average velocity.

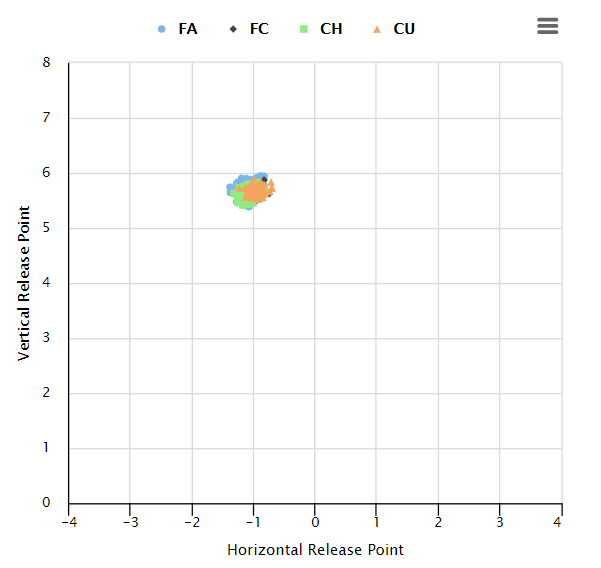

With his two passable breaking balls added to the mix, another one of Weaver’s strengths comes into play. If you want to get the most out of a changeup, you need to throw it from the same release point as your fastball, and Weaver is one of the best in baseball at repeating his release point. All four of his pitches, in fact, come out of his hand at nearly the same point.

The confluence of four usable pitches and great deception has had great results so far this year. All four of Weaver’s offerings are missing bats at career-high or near-career-high rates. His swinging strike percentage is at a career high as well, as you might expect when every pitch is doing well individually. His strikeout rate has rebounded to a healthy 26.6%, and his walk rate has reached a career-low (and top-20 among qualified starters) 5.2%. Unable to stay in the Cardinals’ rotation last year, Weaver has already accumulated 1.5 WAR and is tied with Zack Greinke for most WAR among all Diamondbacks players this year.

Baseball isn’t a static sport, and it’s too early to declare Weaver’s makeover an unqualified success. The first-pitch curveball gimmick isn’t a stable strategy; lean on it too much, and batters will adapt. As much as I’ve praised Weaver’s cutter, it’s still a work in progress; its movement is inconsistent from pitch to pitch, sometimes looking like a flat slider and sometimes like an underthrown four-seamer. For the moment, however, the changes have worked. Both breaking balls are performing well this year, and even in this modern age of advance scouting, opposing batters haven’t yet cracked the code.

Luke Weaver’s career has been a referendum on whether a pitcher can succeed with two plus pitches, athleticism, and little else. One easy answer is “of course that’s enough.” Weaver has been worth 4.6 WAR in his career already, and he accumulated the majority of that with a changeup and some moxie. However, I would argue that Weaver’s 2019 has changed the narrative. Sure, Luke Weaver with only two pitches was a serviceable major league starter. Luke Weaver with four pitches, though, has a 3 ERA and the peripherals to match. Maybe all along we should have been asking ourselves not if Weaver could get by with two pitches, but whether he could excel with three or four.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Ben, another great piece. Been enjoying your work.