Matthew Boyd Is Walking a Fine Line

Matthew Boyd had a tough 2020 campaign. After posting a 3.3 WAR season in 2019, Boyd’s performance cratered last year. His ERA- increased from 97 to 149 and his FIP- 93 to 128. He lost about eight percentage points on his strikeout rate (30.2% to 22.1%) while adding almost two points to his walk rate (6.4% to 8.1%). Boyd was putting close to 10 more batters per 100 faced on the basepaths year over year and the home run troubles he developed in 2019 did not subside.

Through his first four seasons in the majors, Boyd allowed home runs on 12.4% of his fly balls. That figure jumped to 18.2% in 2019 and 19.7% in ’20. Among qualified pitchers, that was third highest in the league, behind Kyle Gibson and Alec Mills. But where Gibson and Mills both posted above average groundball rates (51.5% and 47.3% respectively), Boyd only induced groundballs on 37.2% of his batted balls against. Not only were Boyd’s fly balls leaving the yard at one of the highest rates in the league, he also gave up a lot of them. All these issues culminated in Boyd allowing a .453 wOBAcon and accumulating just 0.1 WAR in 60.1 innings pitched, far off the pace he set in 2019. The former value was by far the worst in the majors in 2020. Indeed, Boyd’s wOBAcon allowed was almost 20 points worse than his next closest peer.

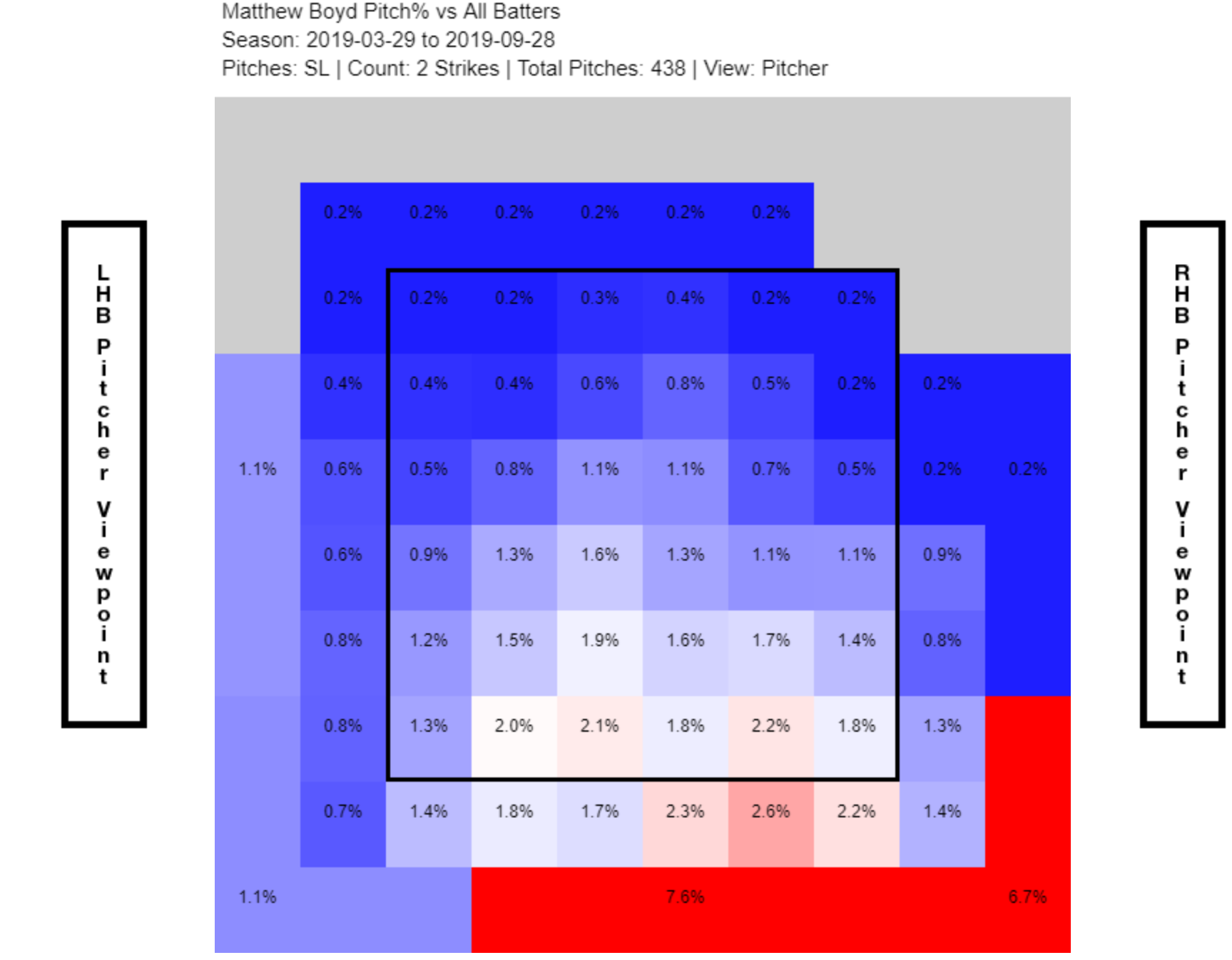

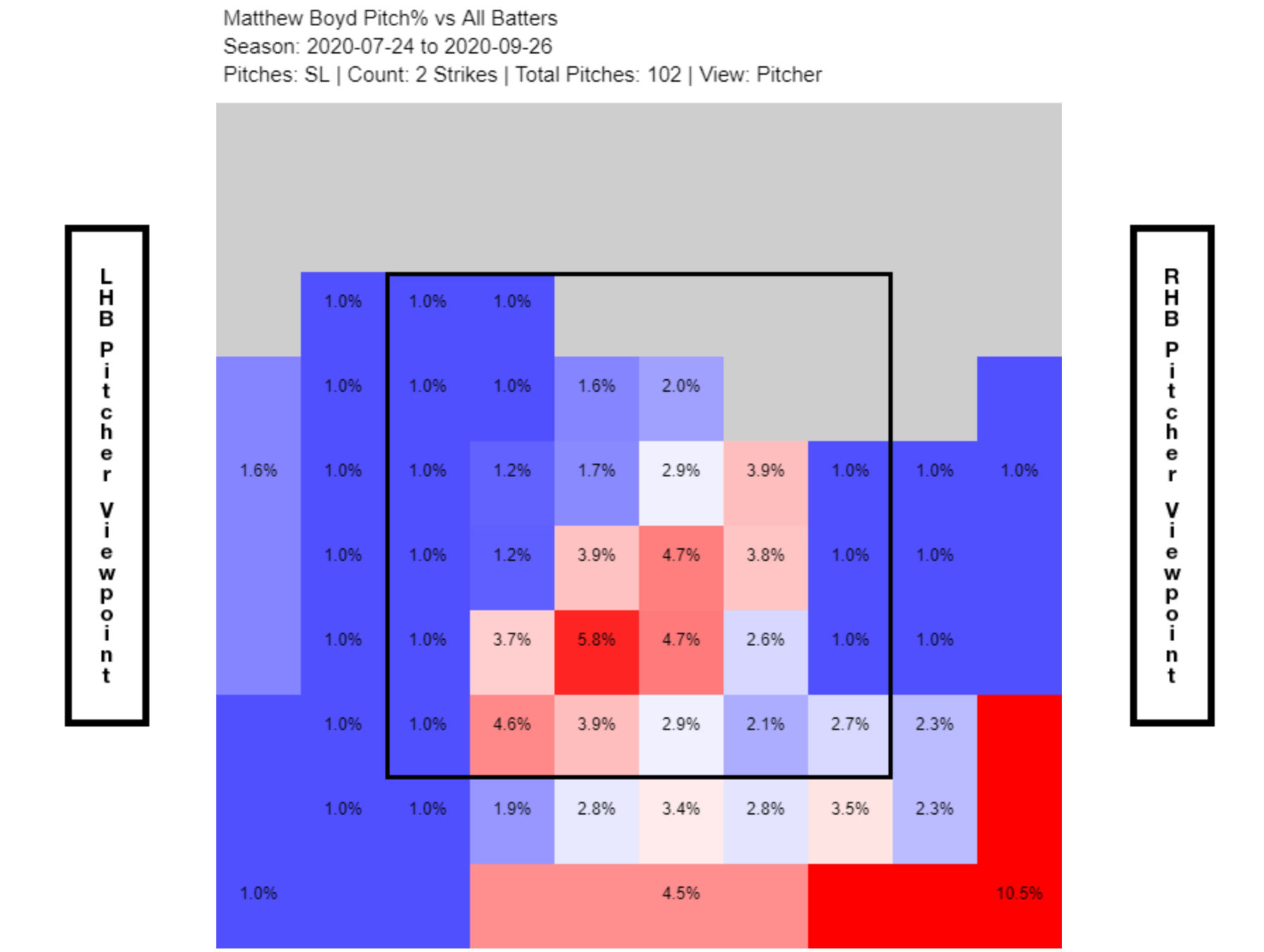

One of the culprits behind his 2020 demise was the degradation of his slider. The pitch was a consistent source of swings and misses in 2019; Boyd threw the slider 22.7% of the time and generated whiffs on 43.6% of swings. He increased its usage to 28.1% in 2020 but the whiff rate tumbled fell to 39.4% — still an impressive figure but given how often he throws the pitch, that is a lot of lost whiffs. He struck out batters with 52.5% of his two-strike sliders in 2020 after 58.5% in ’19, which can be attributed to more sliders finding the middle of the plate last year.

His inability to put hitters away overall was the main driver of the decline in his strikeout rate last season. The percentage of his pitches in two strike counts was almost identical between 2019 (31.7%) and ’20 (29.9%). The rate at which he struck out the opposition in these counts, however, declined precipitously from 52.0% to 41.7%, basically a 20 percent reduction leading to a .330 wOBA allowed in plate appearances that reached two strikes, which is close to league average overall in all situations.

I am burying the lead here but Boyd has been excellent through his first four 2021 starts. He sports a 2.03 ERA and 3.18 FIP. He allowed his first home run in his fourth start (compared to his fifth inning in 2020), bringing his HR/FB rate to a minuscule 3.0%. That has been the main driver of his results thus far. His strikeout rate is almost seven percentage points lower than the league average at 18.1%, but he has been able to offset some of that with a 5.7% walk rate.

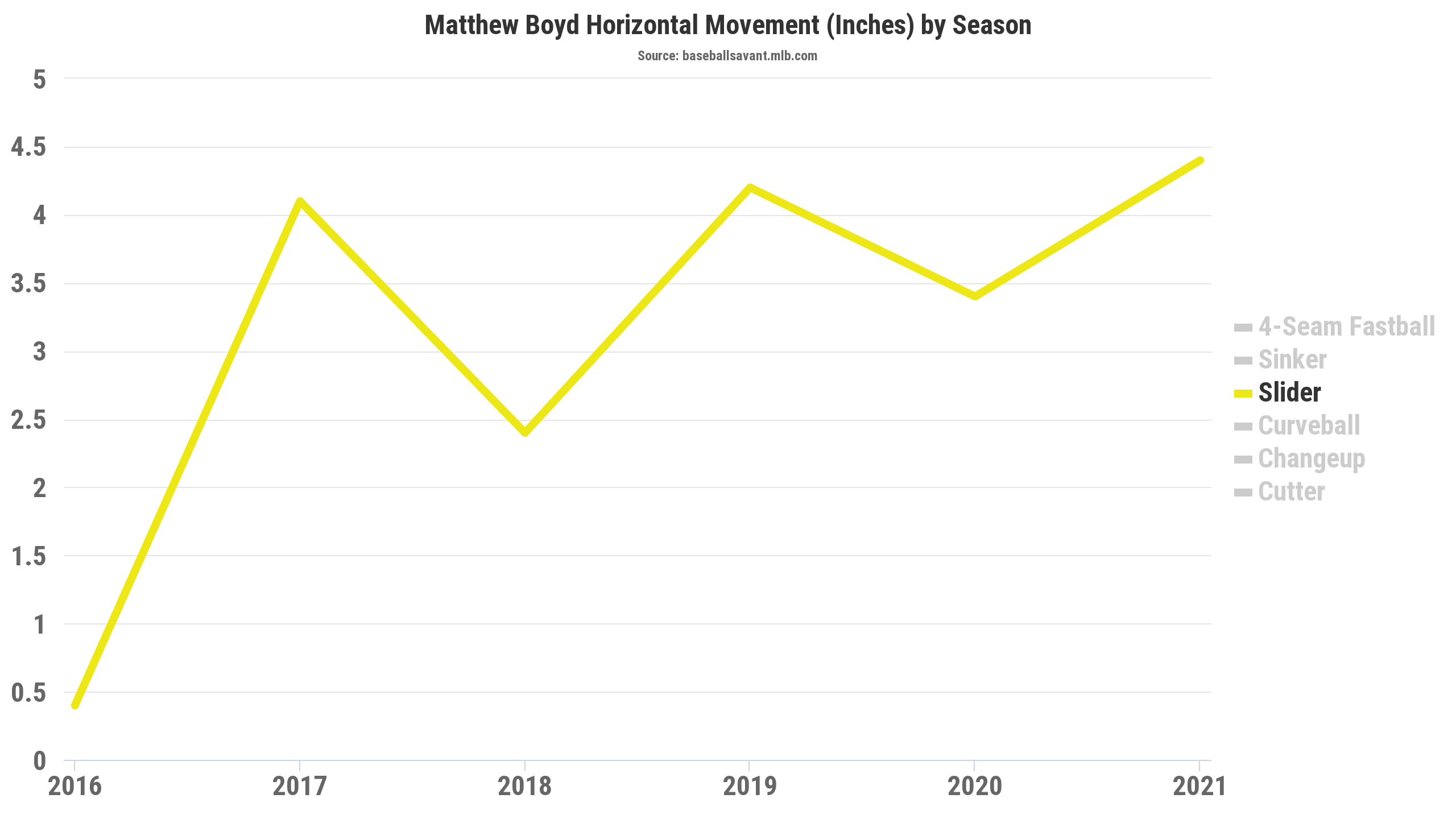

Still, the slider has been an issue in the early going, one that could spell trouble down the line if Boyd’s results on contact deteriorate. His whiff rate on the pitch is down to 18.4%. Through four starts, he is only striking out 35.3% percent of batters with two-strike sliders, much lower than the rates in 2019 and ’20, though I am optimistic he can pick up more punch outs with the pitch moving forward. The movement of the pitch is largely unchanged from his past two seasons:

And he is doing a good job burying it to the glove side corner:

Locating pitches such that the batter has difficulty squaring is generally a positive indicator for the quality of the pitch. But hitters do not seem to be fooled by the sliders at the edge or outside of the zone. Boyd’s two strike sliders in 2019 yielded a 21.9% swinging strike rate. For 2020, that dipped to 17.6%. This year it is all the way down to 8.3% of his two-strike sliders. This is not the result of batters laying off the pitch; the swing rate on these pitches was 57.5% and 52.0% in the previous two seasons and now sits at 60.4% in 2021. Batters are just increasingly putting Boyd’s slider in play, which is not surprising given the pitches decline in put-away rate.

This concern does not carry over to his other pitches. On all non-slider pitches with two strikes, Boyd has induced swinging strikes and called strikes at a 9.3% and 5.3% clip, respectively, compared to 15.1% and 4.9% in 2019 and 13.5% and 2.2% in 2020. The swinging strike rate is still lower but Boyd has bridged some of the gap with more called strikes. That’s is not the case with the slider.

All of this comes together to paint a concerning picture when Boyd gets into pitcher’s counts. As I mentioned above, he struck out 52.0% and 41.7% of batters who reached two strikes in 2019 and ’20. In 2021, that rate has fallen to 36.5%. The main thing keeping his overall run suppression figures afloat is counts that reach two strikes against Boyd are resulting in a .261 wOBA. This is closer to league average than in 2020, but given his strikeout rate in these situations, league average results might be a bit fortunate. The good news is Boyd has been pitching from a more favorable position. He is now throwing 35.1% of his pitches in two-strike counts, which is better than both 2019 and ’20. Any improvements with two-strike sliders will have an outsized effect on underlying numbers because those improvements will affect a greater number of his pitches (assuming his percentage of pitches with two strikes remains steady).

Ultimately, Boyd’s great start comes down to much better results on contact. As I mentioned above, his line is buoyed by the one home run in four starts. His ERA and FIP are impressive but his xFIP sits at 4.81, closer to the 4.97 xFIP from 2020 and much worse than the 3.88 value from ’19. Boyd has allowed just a .270 wOBAcon. His history would indicate he cannot sustain results about 100 points better than league average. There is one source of optimism: he is getting hitters to reach two strike counts. My concern is that when he gets there, he is having trouble putting hitters away with his bread and butter pitch, the slider. This is forcing him to depend on auspicious results on balls in play to keep runs off the scoreboard. I would be surprised if his fortune on contact persists, especially to as large a degree as it has so far.

The Tigers are clearly a rebuilding club. They are probably kicking themselves after not selling high on Boyd in 2019. If the club wants to recoup any promising young players at the trade deadline in 2021, it will need Boyd’s slider to start picking up strikeouts again to offset the dreaded regression on contact allowed.

Carmen is a part-time contributor to FanGraphs. An engineer by education and trade, he spends too much of his free time thinking about baseball.

Al Avila is not kicking himself because it didn’t occur to him at the time that he should have traded Boyd. He’s like Artie Fufkin in Spinal Tap.

To paraphrase Bill James, if anyone is a worse GM than Avila, they’re doing it with a pitchfork.

In general, we underrate amateur acquisition and development and overrate trades / FA. So for better or worse, I think you have to put the Rangers and Rockies below them.

That said, that’s mostly because those other ones have been so bad as opposed to the Tigers being “good” at it. And I do think Avila’s probably going to be done much earlier than the leadership of Texas or Colorado, and it’s hard to argue against that. The system is good but that’s at least partly because they’ve been picking so high.

I guess Jeff Bridich’s doing it with a pitchfork then