Max Fried Has Raised His Ceiling

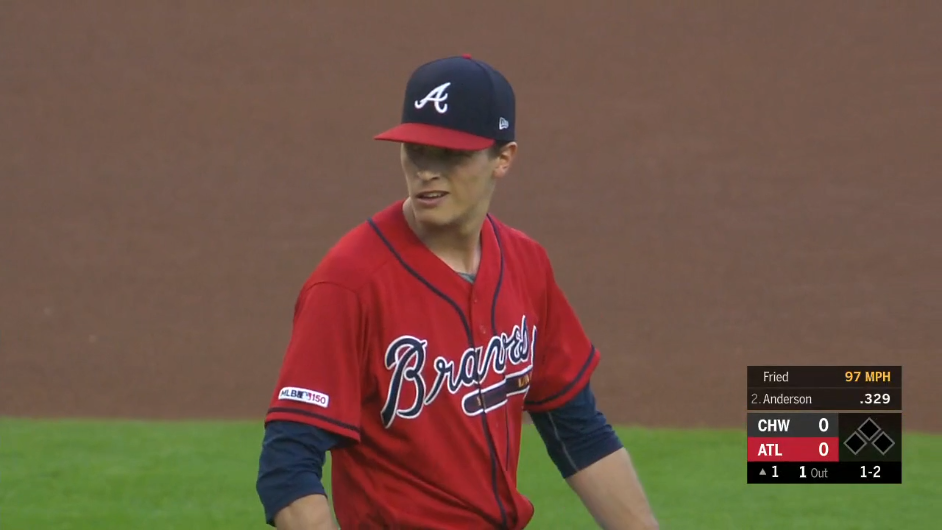

Last Thursday, Max Fried turned in six of the best innings of his young career. Sure, it was against the Chicago White Sox, who are decisively not good at hitting baseballs right now, but still, Fried was dominant. He sat down each of the first 13 hitters he faced, striking out eight of them. Then Eloy Jiménez reached on a softly hit infield single down the third-base line and scored two batters later on a double by Adam Engel. But Fried bounced right back with a scoreless sixth, striking out two more to bring his total for the day to 11. He waved four batters with a curveball, four with a slider, and three with a fastball. After one of them, he made this face.

Folks, I have never looked at anyone like that in my life. Mostly because I have never fired a 97 mph fastball past Tim Anderson, or accomplished anything else that would fill me with a similar rush of adrenaline and personal gratification. Maybe if I really think I did a great job writing this post, I’ll feel so good about it that I’ll slam my laptop shut, strut away from the couch, and make this face at my girlfriend. Probably not, but we’ll see how these next few hundred words go. Might be worth a try. Point is, Fried was feeling himself, and I don’t blame him.

Then it all went away. Jiménez singled again on the first pitch of the seventh inning, this time hitting a 105-mph line drive to right. Then Fried let a 1-2 breaker run in and hit James McCann, and then Yolmer Sanchez reached on an error at first base. After that, Fried was out of the game, and two batters later, he watched Braves reliever Luke Jackson surrender a three-run homer to Welington Castillo, scoring all of the runners he inherited. After allowing just one run on three hits and a walk in his first six innings, Fried allowed all three hitters he faced in the seventh reach, and each one subsequently scored, messing up what had been a very strong performance.

Fried, 25, was better than his final line showed him to be on Thursday, just like he was better than his final pitching line on August 7. That day, he faced the fearsome Minnesota Twins offense on the road, and he retired the first nine hitters he faced with seven strikeouts, cruising into the sixth inning with no runs allowed on three hits, one walk, and 10 strikeouts. Then he allowed the leadoff hitter to reach on an error in the sixth and gave up back-to-back one-out singles before getting lifted from the game, after which he once again watched his teammate Jackson allow the inherited baserunners to score. In fact, Fried’s entire August looks pedestrian — a 3.51 ERA in 33.1 innings — until you peek at his underlying numbers: 42 strikeouts, eight walks, and two homers, good for a 2.38 FIP that was sixth-best in the majors for the month.

It was the best month in a season that has seen Fried quietly take some interesting steps toward becoming a valuable member of the Braves’ rotation. He spent parts of the 2017-18 seasons in the majors splitting time between starting and relieving, and he proved to have serious swing-and-miss stuff (11.76 K/9), but it came with a troublesome walk rate (5.35 BB/9). Those numbers remained consistent regardless of whether he was in the rotation or the bullpen, which gave the Braves good reason to be stubborn about having him start games.

After making two relief appearances in March, Fried has been a full-time starter in 2019 for the first time in his big league career. That’s led to some inconsistency — he recorded a 1.38 ERA in his first six games of the season, then allowed a 5.68 ERA in June — but there have been real signs of progress throughout the year. He’s raised his strikeout rate in every month this season, all the way from 20.5% in April to 29.8% in August, while having his walk rates in those two months remain nearly identical. His contact data has been impressive too: According to Statcast, just two starters have allowed a lower barrel percentage than Fried this year, and neither one of those — Mike Clevinger and Aaron Civale — have been in the majors all season the way Fried has. When setting the standard to 400 batted ball events, Fried has allowed the lowest barrel rate and the second-lowest average launch angle in baseball. Meanwhile, his xwOBA has stayed in the 69th percentile, and his xSLG is in the 71st percentile.

Fried’s effectiveness as a starter has coincided with him adding an important layer to his pitching arsenal. As a reliever, Fried played around with as many as five different pitches, but mostly, he concentrated on his four-seamer, his curveball, and his changeup. His curveball was excellent — a high-spin force (94th percentile in baseball) that was better than the results showed in 2017 and took huge strides last season, inducing a .182 wOBA and .105 xwOBA from opponents. His fastball, which averaged just over 93 mph, was serviceable, producing a .317 wOBA from opponents (.369 xwOBA), but his changeup was a disaster, resulting in a .468 wOBA. If he was going to start, two pitches weren’t going to be enough to sustain him if the fastball didn’t find another gear, and the changeup wasn’t cutting it as a third option.

This season, however, Fried has created a third pitch that’s become a legitimate weapon. It’s his slider, which he’s throwing with 15% of his offerings after never throwing even one in the first two seasons of his career. At 83.8 mph, it is almost exactly halfway between his fastball and curveball in velocity, and it moves with some of the best in baseball. While Fried’s curveball was already an intimidating offering, generating the seventh-most vertical movement in the game, his slider now has the 15th-most horizontal movement, along with well-above-average drop.

That kind of movement has given Fried some very impressive results. With a .228 opponents’ wOBA, the slider has been his best-performing pitch, especially if you go by our pitch weights, which give him a wSL value of 6.7 this season. It holds up well under more predictive figures too, with its .227 xwOBA just a hair off from the curveball’s .196 xwOBA. Fried has taken his mastery of spinning one breaking ball and created a completely different offering that’s just as devastating. You don’t have to take my word for it either. You can ask Justin Turner whether he thought this was a hittable pitch.

Or maybe you can ask NL MVP candidate Cody Bellinger how this pitch simply disappears from his swing path.

Compare those two sliders to this curveball Will Smith saw in the same game.

The effectiveness of those two pitches is the reason Fried has become a somewhat surprising anchor in the Braves’ rotation. With 142.1 innings this season, he’s thrown the third-most frames of anyone on the staff, behind only Julio Teheran and Mike Soroka. Soroka, a rookie, has been fantastic, while Teheran has delivered one of the better seasons of his career, but behind that group has been a rather unstable bunch. Mike Foltynewicz is still trying to figure out what has been a nightmarish season for him, Dallas Keuchel is just now beginning to return to form after an unsteady first several starts of the season, and Kevin Gausman was so ineffective he was released from the team. The Braves are a lock for the postseason, with 100% playoff odds according to our own projections, which means figuring out a postseason rotation that can match up with the Dodgers and beyond is going to be a top priority for the team going forward. With his mini-breakout in 2019, Fried has set himself up to be a crucial third starter when October rolls around.

When the playoffs do arrive, however, the question becomes how can Fried be most effective? Because while his breaking pitches have been dominant this season, his fastball continues to lag behind. It’s picked up a small amount of velocity, but it’s getting hit hard, with a .375 opponents’ wOBA and a .360 xwOBA, according to Statcast. Of the 17 homers Fried has given up this season, 10 have come against the four-seamer. It isn’t one of the most unusable fastballs we’ve seen, but it is something of a liability. And if Fried is going to be throwing valuable postseason innings, it is probably pertinent that he play to his strengths. We’ve seen pitchers with dominant breaking balls lean hard on them in the postseason in recent years. Fried seems like a good candidate to do the same thing.

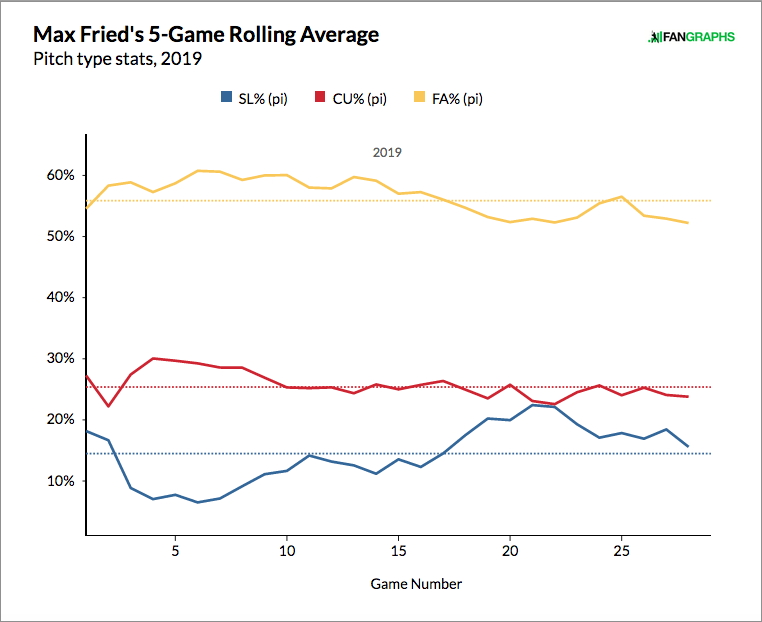

There’s a bit of evidence that he and the Braves are beginning to consider that kind of approach. His four-seam usage, once 60% back in April, has dropped in every month this season, falling to 51.7% in August. His slider usage, meanwhile, has gradually increased, from 7% in April to a peak of 19.4% in July. In terms of rolling averages, Fried’s pitch selection has looked like this:

It isn’t an “Aaron Sanchez gets traded to Houston” level of dramatic change, but there is a trend. Maybe his fastball usage won’t dip much below the 50% mark, and maybe he’ll do just fine with that. It’s worked out well enough to make him the 23rd-most valuable pitcher in the NL this season, after all. But his results are enough to make you wonder: How many breaking balls would be too many for Fried to throw? He’s already one of just 16 pitchers with at least 100 innings this season who have thrown curveballs and sliders with at least 40% of their pitches. Of those, just two — Clayton Kershaw and Madison Bumgarner — throw them over 50% of the time.

Most pitchers wouldn’t dare raise their breaking ball usage beyond where Fried already is, but most pitchers don’t possess two distinct breaking pitches as good as his. Fried has never thrown as many breaking balls as he did last month, and he’s also never pitched better. There’s a good chance that isn’t a coincidence. For a team that needs to get everything it possibly can out of its arms in October, the next month may be a good time for Atlanta to truly test the limits of Fried’s exciting new arsenal.

Tony is a contributor for FanGraphs. He began writing for Red Reporter in 2016, and has also covered prep sports for the Times West Virginian and college sports for Ohio University's The Post. He can be found on Twitter at @_TonyWolfe_.

Are you saying he’s not fried?