Mike Moustakas’ Subtle Adjustment

The last two offseasons have not been kind to Mike Moustakas.

After hitting a Royals franchise record 38 home runs in 2017, Moustakas went into free agency hoping to score a long-term deal. Months went by without a new contract. He was forced to settle in early March, taking a one-year, $6.5 million deal to return to Kansas City.

The Royals traded Moustakas to the Brewers midway through the 2018 season, ending his 12-year tenure with the organization. (Moustakas had been the Royals’ first round pick in 2007.) While he played well, his offensive production took a dip from the year prior. This was particularly true in the power department: Moustakas’ ISO fell from .249 to .208. He posted a 105 wRC+ and 2.4 WAR overall.

Due to improved defense, Moustakas was actually more valuable in 2018 than he was in 2017, but he faced similar issues in his attempt to procure a new contract. Again, Moustakas was forced to wait until late in the game to sign. A February 19 contract with the Brewers — a one-year, $10 million pact with a $7 million mutual option — to be the starting second baseman was the offer he ultimately accepted.

But now, after his second chilly free agency winter, Moustakas has stepped up his game, reaching a new level of offensive performance that we have not previously witnessed.

His numbers are better across the board. He’s already hit 22 home runs, just six shy of his 2018 season total. His 47-home run pace (per 650 PA) would result in a career-high. But in a larger sense, Moustakas has done more than just crank homers. He is getting on base at a higher rate and collecting more hits, many of which have been of the extra-base variety. His .390 wOBA would be a career-high, as would be his 140 wRC+. Moustakas has already produced 2.7 WAR, his highest total in four years and already the third-highest mark of his career. All of which is to say that Mike Moustakas has experienced an offensive surge, and I’m here to tell you why.

Let me preface this by saying that 2019 Moustakas isn’t that different from 2018 Moustakas or even 2017 Moustakas. His batted ball profile is relatively similar. He is hitting more balls to the opposite field, which has slightly reduced the number of shifts he’s seen, but, like most hitters, the majority of his damage still comes when he pulls the ball. Moustakas has a .518 xwOBA on pulled batted balls and a .334 xwOBA when he goes to the opposite field. His quality of contact is Bondsian when going pull and Alex Gordon-ian when going oppo.

So I’m going to say that going to the opposite field more isn’t necessarily the underlying cause of Moustakas’ success. I believe there is another factor that better explains it: It is Moustakas’ improved ability to hit the low pitch. On pitches in the bottom-third of the strike zone in 2018, he posted a .324 xwOBA. That was good — 68th percentile good — but doesn’t even compare to his .452 xwOBA on those types of pitches in 2019. That puts him in the 93rd percentile:

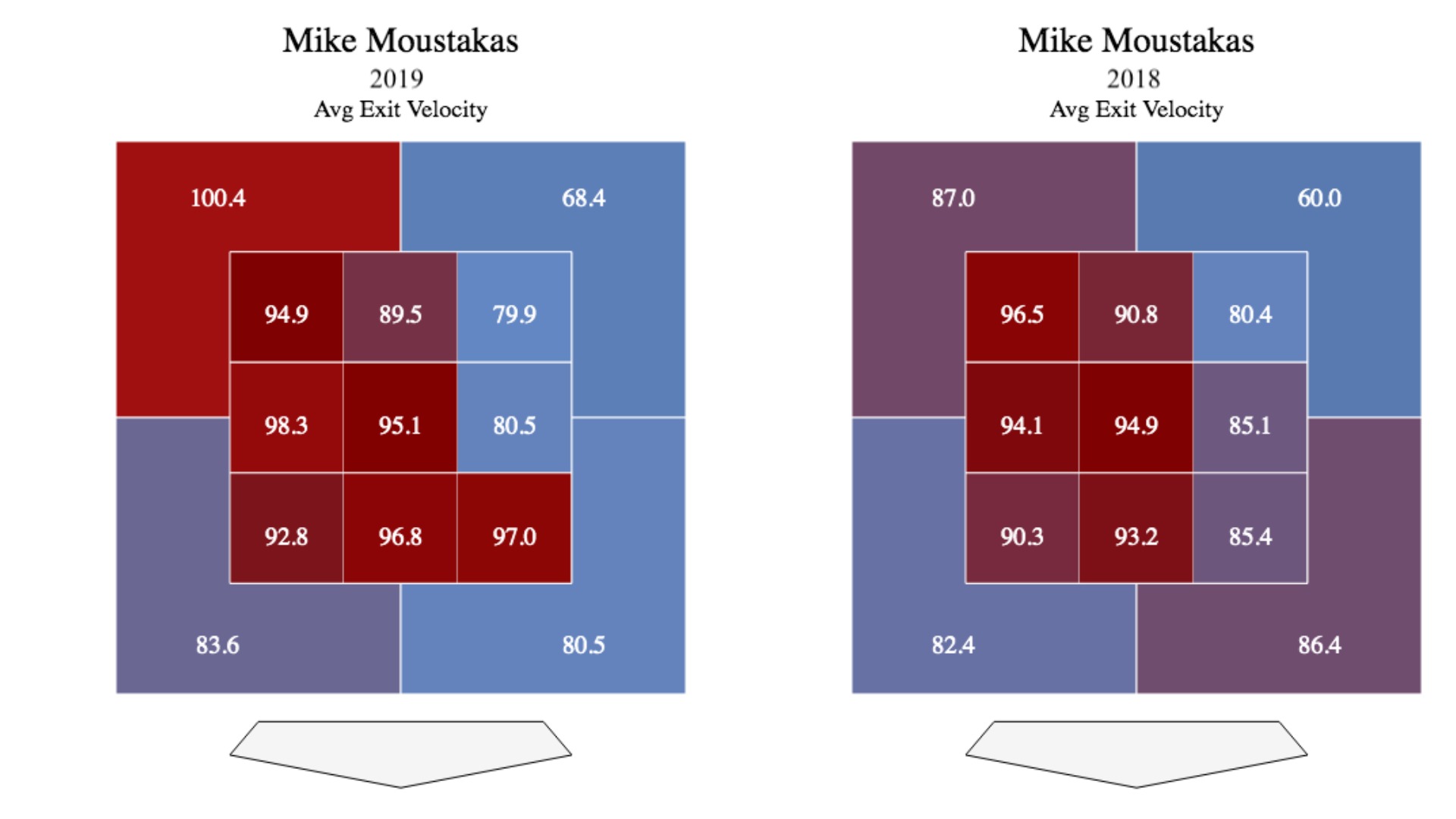

It is clear that Moustakas is crushing pitches in the bottom of the strike zone. To better highlight his year-over-year exit velocity change by zone location, let’s put these data points into table format. (For those unfamiliar, Zone 1 refers to the up-and-outside corner of the strike zone. Zones move from left to right. Zone 9 represents the low-and-inside corner.)

| Zone Location | 2019 EV (mph) | 2018 EV (mph) | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 94.9 | 96.5 | -1.6 |

| 2 | 89.5 | 90.8 | -1.3 |

| 3 | 79.9 | 80.4 | -0.5 |

| 4 | 98.3 | 94.1 | 4.2 |

| 5 | 95.1 | 94.9 | 0.2 |

| 6 | 80.5 | 85.1 | -4.6 |

| 7 | 92.8 | 90.3 | 2.5 |

| 8 | 96.8 | 93.2 | 3.6 |

| 9 | 97.0 | 85.4 | 11.6 |

Three of Moustakas’ four largest exit velocity improvements are in Zones 7, 8, and 9. He has notably crushed pitches that are low-and-in, seeing a near 12 mph exit velocity improvement in Zone 9 specifically.

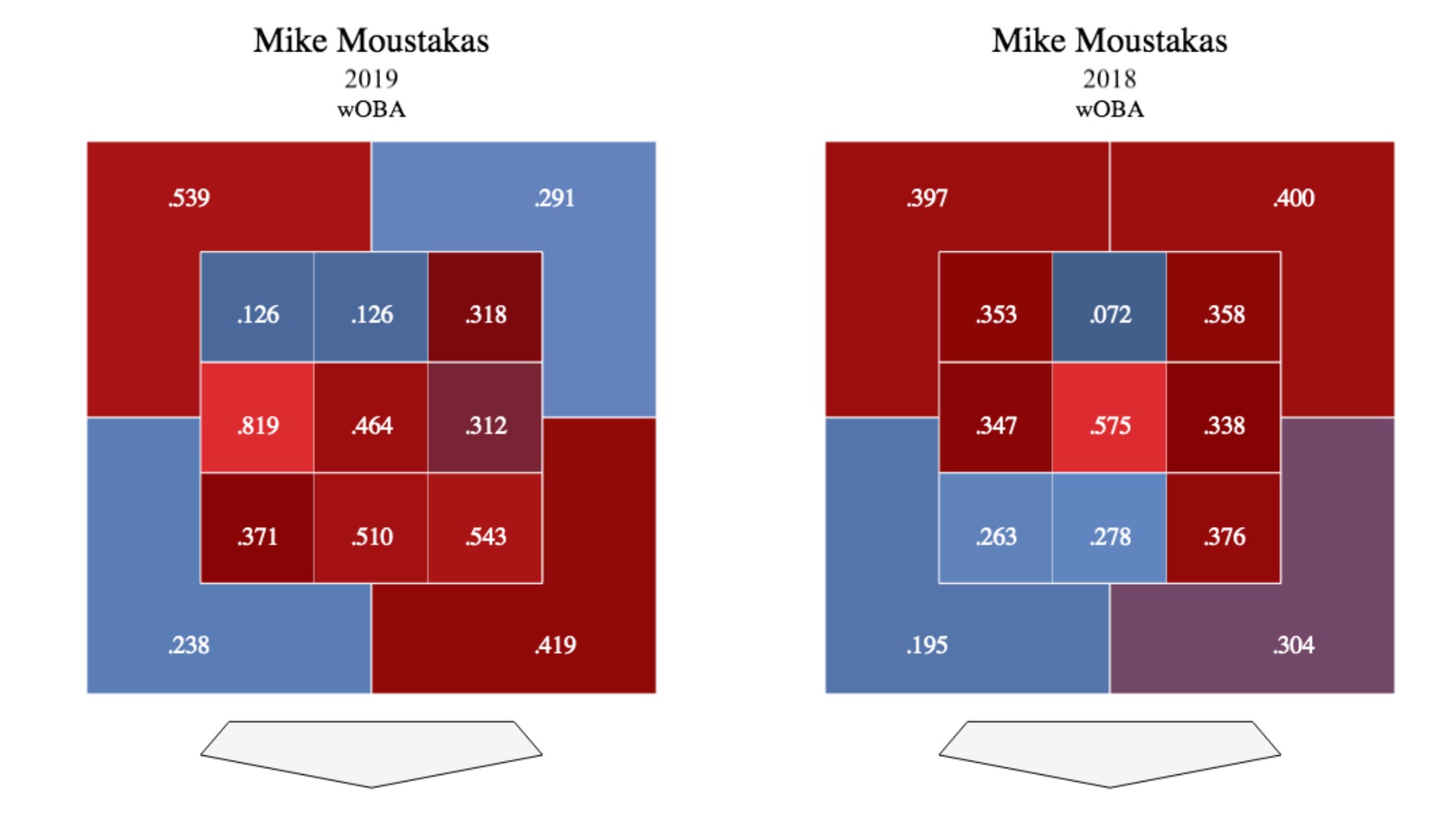

Exit velocity tells a lot of the story, but it doesn’t tell us everything. Even a counting stat as simple as home run total indicates that Moustakas has become a better low ball hitter. This season, he has already hit nine home runs in the bottom-third, already higher than his totals in both 2018 and 2017 (six both years). If you want something more all-encompassing, like wOBA, the narrative persists:

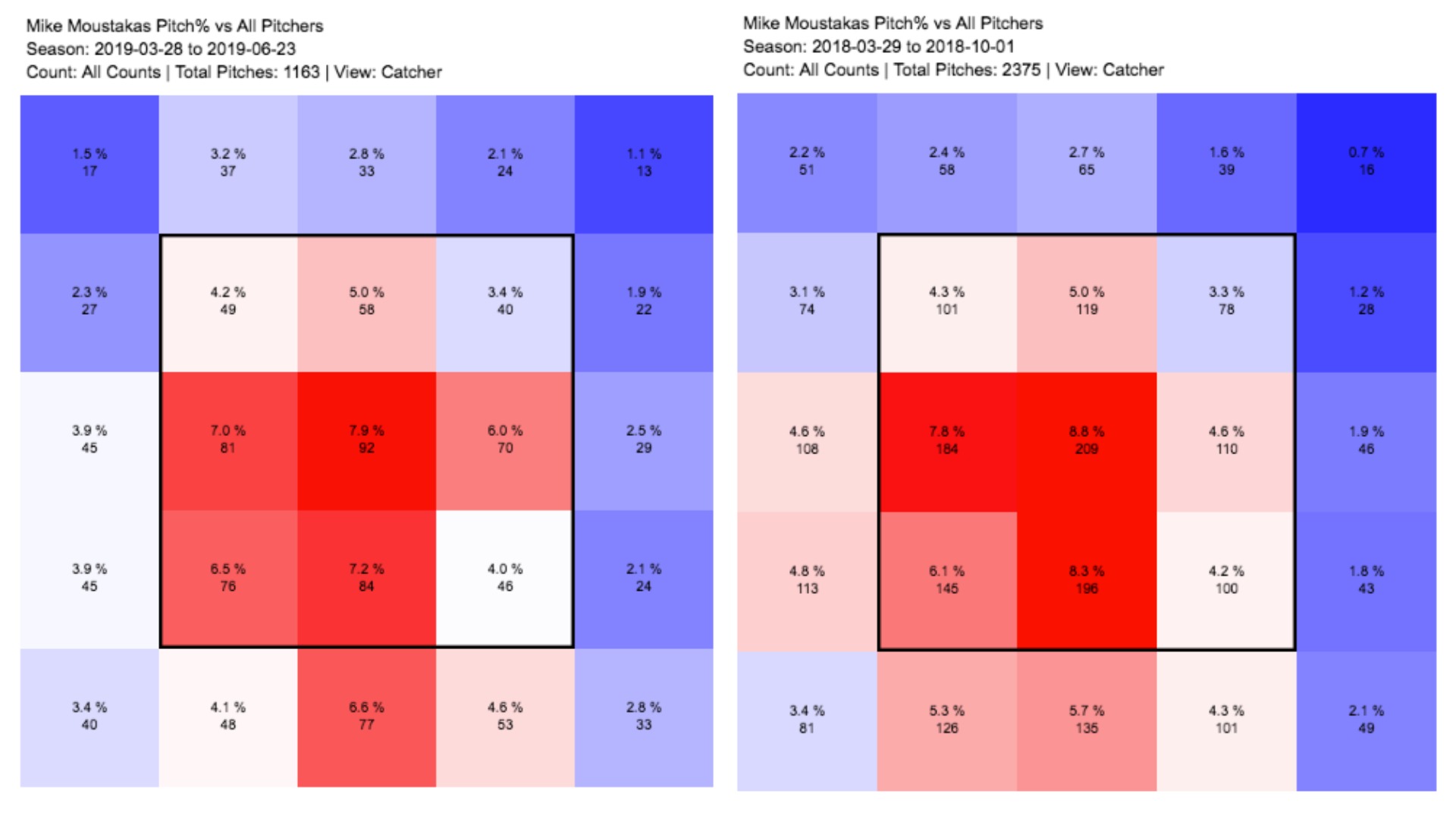

No matter how you slice it, Mike Moustakas has become a dangerous low ball hitter. And for him, that’s really important. Why? Because the bottom-third of the zone is exactly where pitchers try to challenge him:

Of all the pitches that Moustakas has seen this year, 17.7% have been in the bottom of the strike zone. Of the pitches that he has seen in the strike zone, 34.6% have been in the bottom-third. The percentages were similar for Moustakas in 2018: 18.6% of all pitches and 35.5% of all strikes fell in the bottom-third of the zone.

Moustakas’ adjustment boils down to this change. He has started to crush baseballs in the area where he is pitched. It’s no surprise, then, that such an adjustment has led to superlative results.

Now, one might argue that Moustakas has made a second adjustment: an improvement on breaking pitches. By our weighted pitch runs above average metric, Moustakas has been the 13th-best hitter on curveballs and the 15th-best hitter on sliders this season, both significant year-over-year improvements. He has set career-highs in both wOBA and xwOBA on the curveball and the slider.

Considering we’re in an era of baseball that features the fewest fastballs ever, being able to hit the breaking pitch at a high level is a path to success. Moustakas himself has seen either a slider or a curveball 29% of the time this season, so it’s not as if pitchers are throwing him a heavy diet of either. But when they do throw those pitches, they aren’t getting Moustakas out at the same rate as they have in the past, and that has made him a more successful hitter.

Some circular dependency might exist here. It’s highly possible that Moustakas’ second adjustment might be a result of the first. Or, his first adjustment might just be as a result of the second. Among all of the pitches that Moustakas has seen in the bottom-third of the strike zone, 31% fall into the breaking pitch category. So one of two things is happening here. Either Moustakas has improved at hitting all pitches in the bottom of the zone or he has improved at hitting sliders and curveballs, which tend to be in the bottom of the zone.

Is there a definitive way to confirm which is the more prevalent factor? To do so, I decided to look at Moustakas’ performance on fastballs in the top versus the bottom of the strike zone. If Moustakas had vastly improved on fastballs in the bottom of the zone, this would lead us to believe that this is a location, rather than pitch type, adjustment. If Moustakas didn’t really improve on fastballs in the bottom of the zone, this would lead us to believe that this is a pitch type adjustment. In other words, if Moustakas truly improved on low pitches, he should have improved on all low pitches, not just breaking pitches that happen to be thrown low.

The results are rather informative. Moustakas’ xwOBA on fastballs in the bottom-third of the zone has jumped by 55 points; his xwOBA on fastballs in the top-third of the zone has actually fallen by 72 points. This would suggest that Moustakas has improved on pitch location, and that his improvement on breaking pitches is just a result of that larger adjustment.

This season, Mike Moustakas has jumped into elite offensive territory. After two years of struggling to earn a long-term contract, he is likely playing himself into a large payday this winter. Amazingly, it seems to have all happened on the back of one subtle adjustment at the plate.

Devan Fink is a Contributor at FanGraphs. You can follow him on Twitter @DevanFink.

This post deserves more comments, because it is very good.

You are correct. Maybe articles about Mr. MM suffer the same fate as the player himself and Rodney Dangerfield.