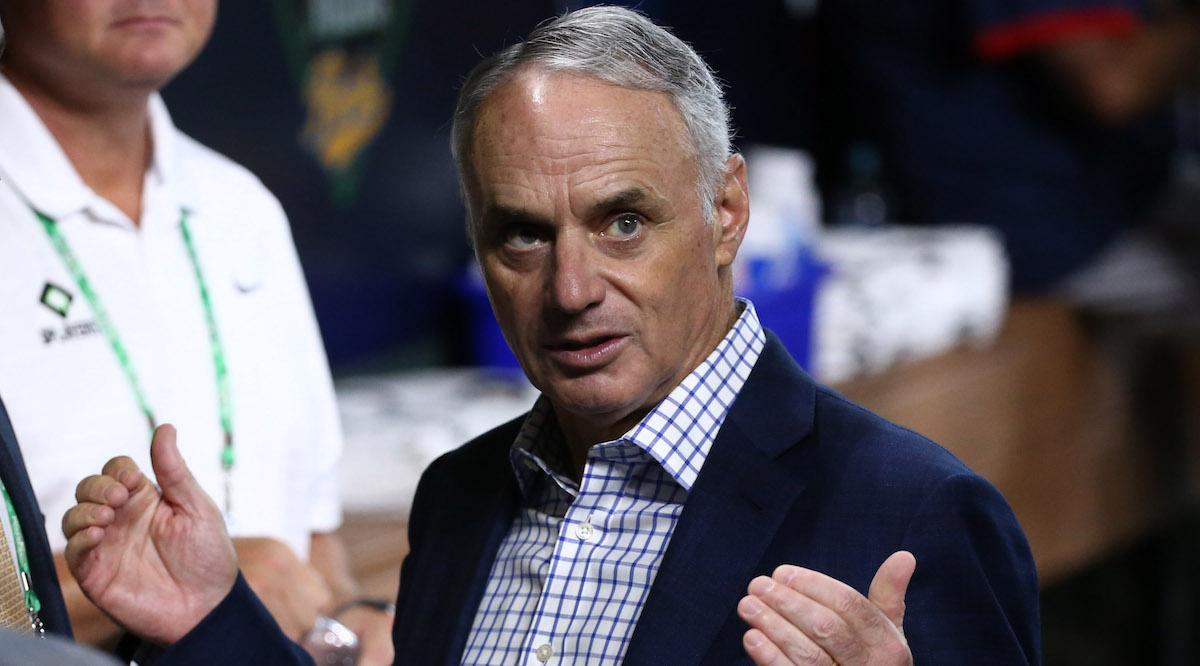

MLB’s Deadline Day Has Arrived — Without a New CBA Deal, of Course

It’s February 28, the deadline set by commissioner Rob Manfred to have a new collective bargaining agreement in place that would end the owners’ self-imposed lockout and allow the season to open as scheduled on March 31 following an abbreviated spring training. To the surprise of no one, there’s no deal yet, even after seven straight days of negotiations between representatives for the owners and the players union in Jupiter, Florida, talks that have stretched into Monday. Negotiations have yielded incremental progress regarding some core economic issues and other matters, but the two sides remain far apart nonetheless. While a league official characterized Sunday’s talks as “productive” after both sides voiced considerable acrimony on Saturday, it would take something on the order of a miracle to have a deal in place by the end of the day.

What’s more, if the league intends to treat the February 28 deadline as a hard one, living up to its threat to cancel games without making them up, and not paying players for a full 162-game season, a deal may become even harder to reach. That would create another issue to settle via negotiations, because the length of a season is subject to collective bargaining; the league can’t unilaterally reduce it. One need only to dial back to 2020 to recall what a fiasco that can become once service time and contract incentives come into play. What’s more, the cancellation of games would raise the possibility of the players answering with some hardball of their own by not agreeing to expanded playoffs for the 2022 season. The union indicated that was possible earlier this month, when the specter of cancellations arose. The value of those expanded playoffs is estimated at $100 million.

On Friday, the two sides made progress on a draft lottery, and on Saturday the players issued a comprehensive proposal in which they backed off significantly on the expansion of the Super Two framework and for the first time since last month lowered their ask on the Competitive Balance Tax threshold. According to multiple reports, however, MLB reacted badly to the proposal, which in turn outraged the players. Sunday did not include an exchange of formal proposals, but there was discussion of potential scenarios along the lines of “if we did X, could you do Y, and so forth,” as The Athletic’s Evan Drellich explained.

With the caveat that things continue to change, here’s where the two sides stand on the major issues entering Monday’s negotiations.

Draft Lottery

The idea behind a draft lottery is to reduce the incentive for teams to use tanking as an easy route towards securing top draft picks. In what appeared to be a promising advance on at least one front, the owners agreed to include the top six picks in a draft lottery; they had previously proposed including only the top four picks, while the union wanted the top seven. The union’s previous proposal included provisions having to do with a team’s revenue-sharing status and market size, as ESPN’s Jeff Passan noted on Thursday:

There's a lot of talk about tanking and how to fix it. This, according to sources, was part of the MLBPA's proposal today — similar to what it has proposed in the past. The league's counter has been simple: the top four picks are subject to a lottery with no other adjustments. pic.twitter.com/Ikz41Wk36h

— Jeff Passan (@JeffPassan) February 25, 2022

The current status of those mechanisms is unclear, but a sticking point emerged in that the owners have tied acceptance of the larger lottery to an agreement on a 14-team expanded playoff format. The union has stuck to 12 teams, concerned that 14 doesn’t provide enough incentive for teams to improve their rosters in an attempt to win their divisions and earn first-round byes. Speaking of which…

Expanded Playoffs

Drellich and Ken Rosenthal offered a glimpse at the union’s proposal for a 12-team format that would represent a departure from MLB’s traditional series formats, and they floated a 14-team version as well. In a page taken from the first round of KBO playoffs, the higher-seeded team would start with a “ghost win,” giving them a substantial advantage that goes beyond simply having home field advantage, as though they were starting a best-of-five series up by one game. Thus, division winners that don’t receive byes would need to win just two games in a four-game series, while Wild Card teams would need to win three games.

The full format was not reported, but presumably in a 12-team format, with six teams per league, the top two division winners would get first-round byes, the third division winner would have the “ghost win” advantage against a Wild Card team, and two other Wild Card teams would play a best-of-three on even footing. In the 14-team version, with seven teams per league, the top division winner would get a bye, two division winners would get ghost wins, and two Wild Card teams would play a traditional best-of-three.

(Colleague Dan Szymborksi had his own proposal for a 14-team format that would effectively grant two ghost wins to the division winner in a best-of-five by requiring the lower-seeded team to win three straight games.)

Arbitration Eligibility

Initially, the union sought to make every player with at least two years of service time eligible for arbitration, up from the 22% eligible via the Super Two system since 2013. In last week’s proposal, they lowered that to 75%, coupling with it an increase to their minimum salary and pre-arbitration bonus pool offers. On Saturday, they came down much further than before, to 35% of all players with between two and three years of service time, and with that moved slightly downward on the Competitive Balance Tax threshold. So far, the league has completely refused to expand beyond 22%.

Minimum Salary

On Friday, MLB added $10,000 to each year of its flat minimum proposal and dropped its tiered service time alternative. The league is now proposing minimum salaries that rise from $640,000 to $680,000 from 2022-26, up from last season’s minimum of $570,500; teams would still be able to give discretionary raises to players as their service time increases, but would also be able to unilaterally renew contracts with smaller or no raises as well, just as they have for ages. The union’s latest proposal starts with a $775,000 minimum for 2022, rising by $30,000 per year to $895,000. Here’s a table that incorporates the two current proposals with a look back at the minimums from the past two CBAs:

| Year | Minimum ($K) | Annual Change |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | $480.0 | 15.9% |

| 2013 | $490.0 | 2.1% |

| 2014 | $500.0 | 2.0% |

| 2015 | $507.5 | 1.5% |

| 2016 | $507.5 | 0.0% |

| 2017 | $535.0 | 5.4% |

| 2018 | $545.0 | 1.9% |

| 2019 | $555.0 | 1.8% |

| 2020 | $563.5 | 1.5% |

| 2021 | $570.5 | 1.2% |

| MLB Current Proposal | ||

| 2022 | $640.0 | 12.2% |

| 2023 | $650.0 | 1.6% |

| 2024 | $660.0 | 1.5% |

| 2025 | $670.0 | 1.5% |

| 2026 | $680.0 | 1.5% |

| MLBPA Current Proposal | ||

| 2022 | $775.0 | 35.8% |

| 2023 | $805.0 | 3.9% |

| 2024 | $835.0 | 3.7% |

| 2025 | $865.0 | 3.6% |

| 2026 | $895.0 | 3.5% |

Service Time

Via ESPN, the league has agreed to give credit for a full year of service time to players who finish first or second in their league’s Rookie of the Year voting as long as they are among the top 100 prospects and did not spend the full season on the big league roster. Which outlet’s top 100 list they would use was not reported, but like the use of various versions of WAR to determine rankings for pre-arbitration bonuses, most parties involved in such rankings are concerned about their lists being deployed to such ends.

Rules Changes

Back in December, Manfred indicated that on-field rule changes would not be on the table during negotiations, though since then, it’s been reported that the two sides have agreed to implement the universal designated hitter. The league has now proposed that it be allowed to implement rule changes such as a pitch clock by giving formal notice 45 days in advance, instead of a full year. The players “reacted negatively” to that one, according to Rosenthal.

Competitive Balance Tax Thresholds

In what still appears to be the top priority for the players, who feel as though the CBT is a salary cap by another name, both sides moved on Saturday with regards to the tax thresholds, but at best we might characterize those movements as eensy and teensy. The union lowered its 2023-25 tax thresholds by $2 million apiece but left in place both the ’22 and ’26 ones ($245 million and $271 million, respectively). The owners didn’t like that, and responded by offering only a $1 million increase to the 2023 threshold. The insult was intentional; as ESPN reported, “MLB characterized its tax proposal as intentionally lousy, in response to a union tax proposal teams felt was equally lousy.”

There’s been almost no movement in the numbers over the past several weeks:

| Year | Threshold ($Mil) | Annual Change |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | $178 | 0.0% |

| 2013 | $178 | 0.0% |

| 2014 | $189 | 6.2% |

| 2015 | $189 | 0.0% |

| 2016 | $189 | 0.0% |

| 2017 | $195 | 3.2% |

| 2018 | $197 | 1.0% |

| 2019 | $206 | 4.6% |

| 2020 | $208 | 1.0% |

| 2021 | $210 | 1.0% |

| MLB 1/13 Proposal | ||

| 2022 | $214 | 1.9% |

| 2023 | $214 | 0.0% |

| 2024 | $214 | 0.0% |

| 2025 | $216 | 0.9% |

| 2026 | $220 | 1.9% |

| MLB 2/12 Proposal | ||

| 2022 | $214 | 1.9% |

| 2023 | $214 | 0.0% |

| 2024 | $216 | 0.9% |

| 2025 | $218 | 0.9% |

| 2026 | $222 | 1.8% |

| MLB 2/27 Proposal | ||

| 2022 | $214 | 1.9% |

| 2023 | $215 | 0.5% |

| 2024 | $216 | 0.5% |

| 2025 | $218 | 0.9% |

| 2026 | $222 | 1.8% |

| MLBPA 1/24 Proposal | ||

| 2022 | $245 | 16.7% |

| 2023 | $252 | 2.9% |

| 2024 | $259 | 2.8% |

| 2025 | $266 | 2.7% |

| 2026 | $273 | 2.6% |

| MLBPA 2/27 Proposal | ||

| 2022 | $245 | 16.7% |

| 2023 | $250 | 2.0% |

| 2024 | $257 | 2.8% |

| 2025 | $264 | 2.7% |

| 2026 | $273 | 3.4% |

Rather than ordering the formal proposals chronologically in the table above, I’ve kept each side’s proposals adjacent to each other to illustrate how little they have differed. And again, it’s worth pointing out that over the past decade, the CBT threshold hasn’t kept pace with revenues, and that the annual increases of the owners’ thresholds fall short even of a typical 2-3% cost-of-living adjustment, let alone the rate of inflation. Had the 2012 threshold increased by 5% annually, the 2021 base threshold would have been around $290 million, as MLB Trade Rumors’ Tim Dierkes wrote recently.

In addition to the still-sizable gap between the two sides on the thresholds, they’re far apart on tax rates:

| Amount Payroll Exceeds Base Tax Threshold ($M) | 1st-Time | 2nd-Time | 3rd-Time+ | Draft |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017-21 | ||||

| <$20 (Base Tax Rate) | 20% | 30% | 50% | — |

| $20-$40 (Base Tax + 1st Surcharge Rate) | 32% | 42% | 62% | — |

| >$40 (Base Tax + 2nd Surcharge Rate) | 62.50% | 75% | 95% | (1) |

| MLB 2/27 Proposal | ||||

| <$20 (Base Tax Rate) | 45% | 45% | 45% | (2) |

| $20-$40 (Base Tax + 1st Surcharge Rate) | 67% | 67% | 67% | (2) |

| >$40 (Base Tax + 2nd Surcharge Rate) | 100% | 100% | 100% | (2) |

| MLBPA 1/24 Proposal | ||||

| <$20 (Base Tax Rate) | 20% | 30% | 50% | — |

| $20-$40 (Base Tax + 1st Surcharge Rate) | 32% | 42% | 62% | — |

| >$40 (Base Tax + 2nd Surcharge Rate) | 62.50% | 75% | 95% | — |

(2) = second-round pick surrendered for teams in Tier 2, first-round pick surrendered for teams in Tier 3

Until Saturday, the league was proposing marginal tax rates of 50%, 75%, and 100% for the three tiers, so they did come down, but only by a bit. They’ve done away with the repeater penalty from the previous CBA, but the first-time rates for the two highest tiers are still higher than the third-time rates from before, and the first-time rate for the lowest tier isn’t that much lower. The players have preserved the old tax rate structure, minus the draft pick penalty for third-time repeaters.

On Sunday, Drellich reiterated that the league has tied eliminating the qualifying offer system to higher tax rates. As Dierkes summarized earlier this month, “I think that in MLB’s eyes, they are offering to transfer the burden that a certain number of players at the top of each free agent market bear under the qualifying offer system to the team level as a CBT penalty… I would guess that the MLBPA doesn’t consider this an even trade whatsoever, and has likely told MLB as much.”

While it’s possible that the two sides could make enough progress on Monday for MLB to keep the window for an agreement open long enough not to wipe out games, the above is a long list of items, but still only a partial one. If there’s one thing to bank upon in these negotiations, it’s that the two sides will find a way to be at odds over just about everything.

Still, through all of this, it’s worth remembering that this lockout belongs to the owners and to Manfred. Not that it wasn’t entirely apparent from over half a century of MLB labor history, years and years of skyrocketing franchise values, and Manfred’s ridiculous dissembling about how the returns on investment for owning teams don’t keep pace with the stock market, but the recent release of the Braves’ financials — which show that the team made a $104 million profit in 2021 — has undercut the entire premise of the owners’ tight-fistedness. The game is swimming in cash, and television rights fees are on the rise; there was no need to initiate the lockout, and the owners can easily afford to give the players something more than cost-of-living increases. By walling off certain topics such as the Super Two threshold and revenue sharing, and by making the CBT structure even more punishing to teams that want to spend money, they’ve made these negotiations even more difficult than they would otherwise be, and the cost of that will likely be less baseball and more acrimony. Manfred and the 30 owners own this mess, and if games start disappearing, it won’t be any easier to clean up.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

These are minor points compared to how far apart they are on the big ones, but I really hate the idea of “ghost wins” in the playoffs and the possibility of the rules changing in the middle of a season. Those both just seem like really bad ideas.

I actually don’t hate the format where the wild card team needs to win three of four (although I do hate calling it a 5 game series with “ghost wins”). I like the idea of a substantial penalty for the WC team, but Szymborski’s proposal where they need to win three of three is too harsh.

Agreed, “ghost wins” are idiotic, smart people over thinking it. Playoff baseball is great, more playoff baseball is greater. If you are an old school fan that loves regular season that celebrate that. Every other sport includes many more teams and the excitement isn’t hurt at all. I grew up with 4 teams in the post season and the current format of 10 has not negatively impacted my fanship, in fact it has increased my excitement for October.

The idea that increasing playoff team number will somehow decrease teams trying to win is esoteric at best in practice. A larger field will make more teams try to make the lowered bar.

There’s such a thing as the law of diminishing return. And at some point, playoff expansion could even become a net negative…

The first couple rounds of the NBA playoffs are a formality, really. And the regular season means nothing. People still watch, but with 16 teams (really 20) who make the playoffs, the regular season is just a cash grab. The difference between the NBA and MLB is that 8th seeds are basically helpless against 1 seeds. Any MLB team can beat another in a best of 3, 5, or 7. Obviously the first round of the MLB playoffs won’t be 7 games, but even the Orioles can beat the Rays or whoever. IDK it’s just going to be very lame when an 81 team knocks out a 96 win team or something (it’s going to happen).

How about all 30 teams compete in a summer-long tournament of 3 game playoff series, for a total of 162 playoff games? This would be the maximum amount of playoff baseball, therefore the best possible outcome.

This is the only possible endgame.

I agree with Steveo on diminishing returns. Small sample size, but in the NFL playoffs last year, first round games were decided by an average of about 17 points. People watched, of course, but they did not make a compelling case for putting more teams in the postseason beyond having more inventory to sell to the networks.