No Extra Extras! Nine Innings Appears to Be Plenty in 2023

On Wednesday night in our hazy nation’s capital, Nationals shortstop CJ Abrams came to the plate looking to extend his team’s last-ditch rally, down four runs to the visiting Diamondbacks with two on and two out. The Nats had dropped three straight and six of their last eight but were looking for a series victory against a surging Arizona team that had taken 11 of its last 16 and first place in the NL West. With Abrams ahead 2–1, a mulleted and mustachioed Andrew Chafin delivered a fastball low in the zone; the 22-year-old drove the ball hard into the dirt and right at Ketel Marte, who flipped to Nick Ahmed for a force out to end the rally and the game.

It was a game more notable for the atmosphere it was played in – one so clouded by wildfire smoke that Thursday’s series finale would be postponed — than for anything in the box score. But just by its unremarkable nature, the close of Wednesday’s contest kept alive a streak that is reaching historic length: 61 straight games — the entire season so far — without extra innings.

In the Modern Era, just five other teams have gone this deep into a season without playing a single inning of bonus baseball. Dating back to last year, the Nats have finished 67 straight games in regulation (or quicker than that, in the case of a rain-shortened 8–1 loss to the Phillies last October), their longest streak in franchise history. The streak has featured 19 games decided by one run and another 14 decided by two, but all have been decided with no more than 54 outs.

What’s even more remarkable about Washington’s streak is that it isn’t even the longest active one in baseball right now. After losing to the Giants on Thursday in a game that was briefly tied with one out in the ninth inning, the Rockies have now played 75 games without needing to break a tie, including the first 64 of 2023. The only Modern Era teams to go deeper into a season without playing in the 10th are the 1958 Tigers (65 games), the 2002 White Sox (69 games), and the Joe DiMaggio of this type of streak, the 2005 Red Sox, who didn’t play an extra-inning game until the 99th game of the season on July 25th — and then played two straight. As improbable as these streaks are, it’s even more improbable that two would coincide like this.

| Team | Season | Games | First Extra-Inning Game |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red Sox | 2005 | 98 | July 25 |

| White Sox | 2002 | 69 | June 18 |

| Tigers | 1958 | 65 | June 28 |

| Rockies | 2023* | 64 | – |

| Mariners | 1992 | 64 | June 18 |

| Nationals | 2023* | 63 | – |

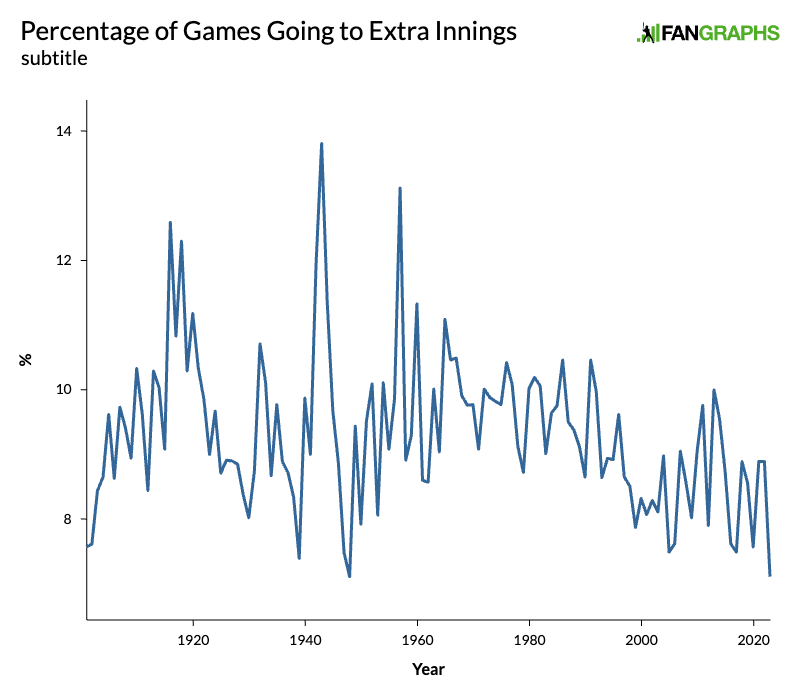

Baseball’s dearth of overtime play is not limited to these two streaking clubs, though. Through Thursday’s games, just 7.1% of games this season had finished nine innings inconclusively, the lowest rate since 1948 and second-lowest in 123 seasons of the Modern Era. Of the 99 games played in the month of June, just four have gone into extras, including last night’s ten-inning, back-and-forth affair between the Braves and Mets that ended with Ozzie Albies‘ three-run walk-off homer.

In each of 2021 and ’22, 216 games went to extra innings (a statistical improbability in its own right). That’s a rate of 8.9%, about 1.8% — or 43 games — higher than this year’s. That rate has dipped below 8% in a number of recent seasons, but only below 7.5% in three Modern Era seasons: 1939 (7.4%), 1948 (7.1%), and this year. Add to that the automatic runner rule, which has shortened the average extra-inning game considerably, and we are getting far less free baseball than we used to.

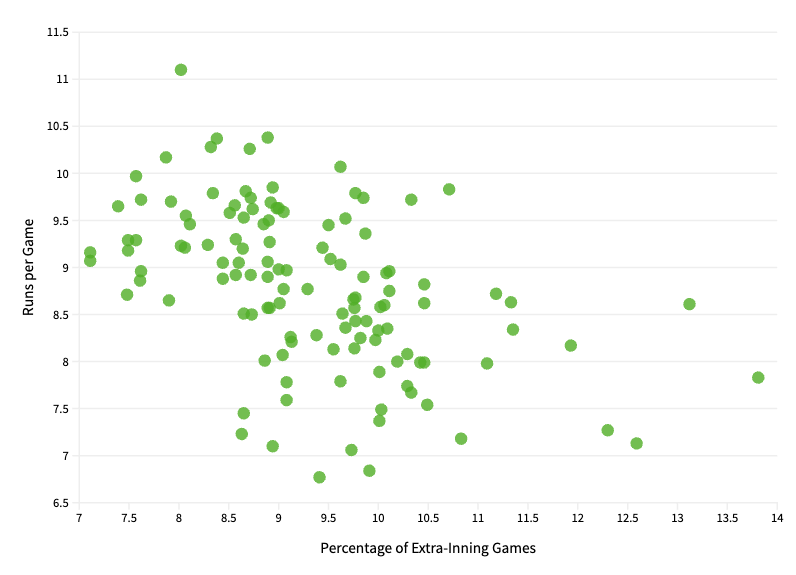

Is this anything more than the randomness of playing hundreds of games with dozens of outcomes with similar likelihoods? More run-scoring does contribute to lower rates of extra-inning games. We see this pattern throughout baseball history, which makes sense: less scoring means a greater likelihood of any given team ending up with two or three runs, which means a greater likelihood of both ending up there after nine innings.

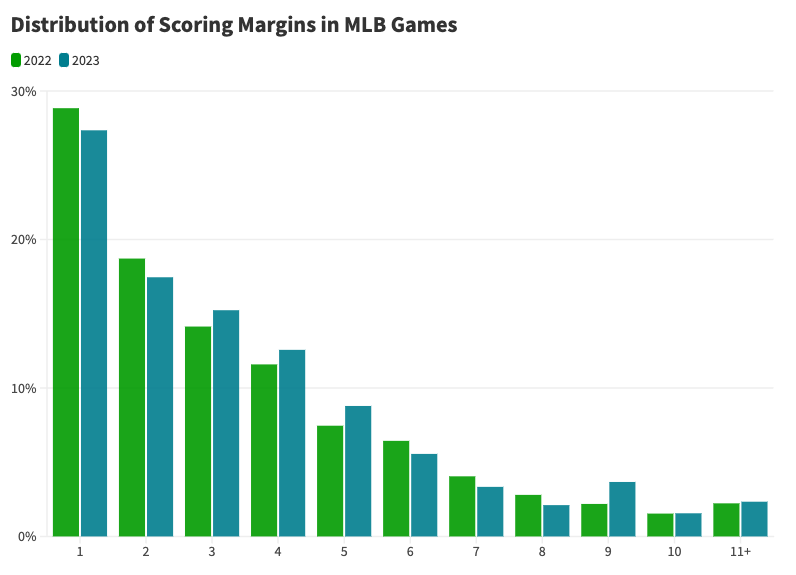

Scoring has jumped up about half a run for home and away teams combined this year, and with more scoring has come broader margins of victory on average, up from 3.46 runs last year to 3.55 this year. Fewer games are being won by one or two runs, and more are being won by three to five:

But 2023 is not some historic scoring anomaly by any means; in fact, the 9.07 runs both teams are averaging is right around the median from the last two decades. In the scatter plot above, 2023 is snug with 1948 in the leftmost area of the graph, way at the edge of percentage of games going into extras, and comfortably in the middle of the pack in terms of scoring.

Back to those margins: aside from overall scoring going up, another factor that could contribute to fewer tight games is to whom those runs are being distributed. Not every team is equally likely to end up with two runs or eight runs; the more that games feature teams with broadly different scoring expectations, the less likely it would be for those teams to end up even after nine.

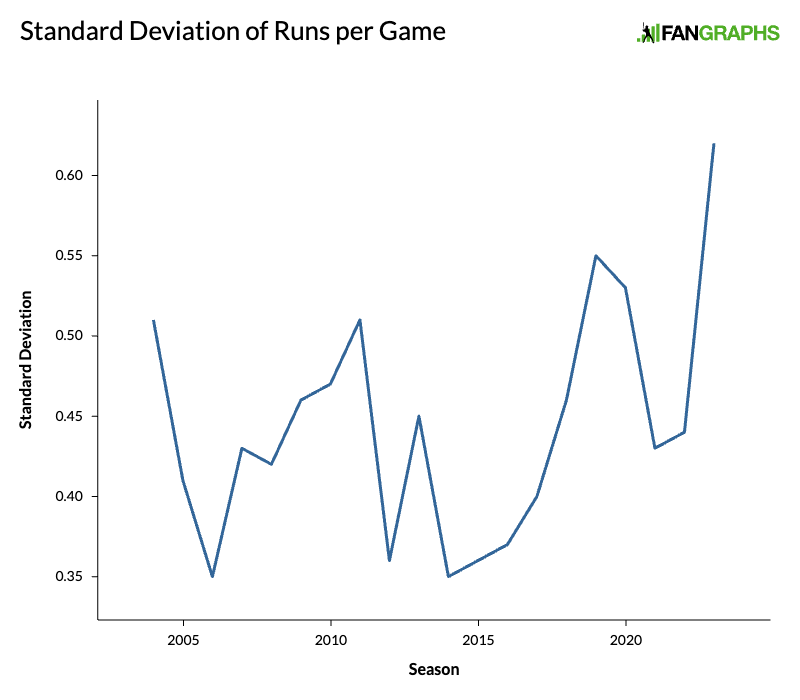

This season is a season of haves and have-nots when it comes to run scoring. The Rangers, Rays, and Dodgers are up over 5.5 runs per game, but the Tigers, A’s, Guardians, and Royals are well shy of four. Across all the league’s offenses, the standard deviation of runs per game values is .62, up 40% from the .44 figure last year and by far the highest in the last 20 years. There’s still some time for this to adjust toward a more typical level, but that could explain why fewer games are ending regulation in a tie. This season features teams with profoundly different expectations for how many runs they’ll score in any given game.

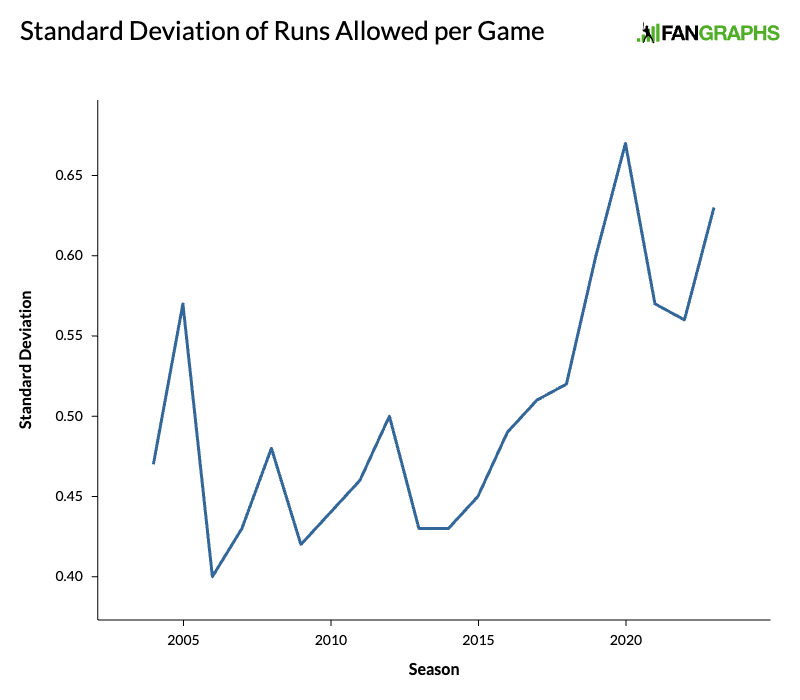

The story on run prevention is similar, with the standard deviation of runs allowed per game increasing from .56 in 2022 to .63 this year — not quite the highest value in the last two decades, but second only to 2020. Then again, the A’s giving up 6.7 runs per game, more than a run higher than anyone else, is skewing this figure just a bit.

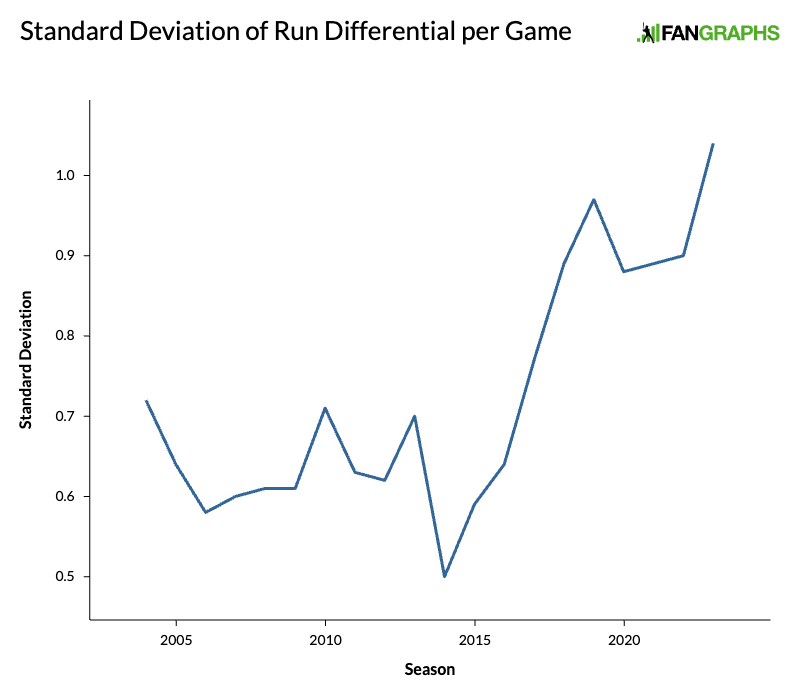

What’s more is that some of the haves and have-nots are the same teams on both sides of the ball. The Astros, Rays, and Braves, for instance, are among the top 20% of the league on both sides; the Royals, Nationals, White Sox, and those A’s find themselves struggling to score runs and prevent them. The standard deviation of teams’ run differential per game has spiked up dramatically in the last decade, from .50 in 2014 to around .89 in the last three seasons, reaching new heights at 1.04 this year. This is a much bigger issue than just a quirk leading to fewer extra-inning games; it should be a huge red flag for any league trying to keep its games competitive. The broader the gaps are between the expected performance of the two teams on the field, the more often the better of those teams will outplay the other — and the more likely they’ll be able to do so in nine innings.

As it turns out, this isn’t a story about (ultimately meaningless) streaks of games without extra innings, but instead a story about disparity. There’s so much chance built into the rates of extra-inning games, but the bottom line is that if you’re looking for more competitive games overall, more even talent distribution would be a good place to start.

You may have heard about the shorter games this year; the way I see it, shaving nearly half an hour off of the average time of a nine-inning game is a huge win for baseball. But none of MLB’s game-shortening efforts have targeted the rate of games going to extras, and for good reason: heading into extra innings is a good sign you have a good game going. Here’s hoping for more bonus baseball the rest of the way.

Chris is a data journalist and FanGraphs contributor. Prior to his career in journalism, he worked in baseball media relations for the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox.

Maybe it’s just the universe expressing displeasure at the travesty that is the Manfred man. Or I suppose it could just be the A’s (etc) are really bad.

No one likes that Manfred man…he should be earth-banned

Come all with bats, come all with balls

You should see nothing like the Manfred man

Agree that it’s a travesty, but I also feel compelled to raise awareness for the superior term “zombie runner” over Manfred man (which is fine) or, god-forbid, ghost runner.

Zombie runner over ghost runner.