Oliver Drake Changed His Game and Found a Home

Far from the bright lights of the pennant chase, history was made last August when Oliver Drake came in to pitch the ninth inning of an 8-2 Twins victory. That appearance marked the fifth major league team Drake had appeared for in 2018 alone. He wasn’t done there; Drake changed teams a further three times in the offseason, with some of the transactions just seeming silly:

Drake was good-natured about the whole ordeal, appearing on Effectively Wild to talk about his odyssey. Still, he was clearly eager to put the past behind him and find a home on a single roster. No one gets into baseball in hopes of endlessly bouncing between teams, good enough to play in the majors but replaceable enough to frequently be a roster crunch casualty.

If you haven’t been following closely this year, you might not have heard anything about Drake. Did he slip off the edge of major league relevance, stuck in the purgatory of Triple-A Durham? Nope! Neither did he continue his travels across the major leagues. Instead he got better, and he now figures into the Rays’ bullpen plans for the rest of the regular season and beyond.

How did a reliever who had previously defined the word journeyman turn into a key cog in one of the best bullpens in baseball? For lack of a better way to say it, Drake essentially took every part of his game and made it better. In a world of nonstop player development and video-aided pitch design, no player is ever truly a finished product, and even marginal ones are seemingly a tweak away from being effective; Drake is the perfect example of that.

Every time I watch Drake, it feels like a minor miracle that he can throw a single pitch without irreparably damaging his arm. His throwing hand drops behind him, seemingly to the ground, before he whips it over his head to deliver the pitch:

The resulting arm angle is bizarre. Drake tilts his shoulders hard as he releases the ball, resulting in a high arm slot despite a sidearm-looking arm angle. In fact, he gets over the ball so much due to his delivery that his fastball breaks to his glove side — his four-seam fastball has the second-most gloveside movement of any pitcher who has thrown at least 100 of them this year.

Combine that weird movement with the fact that Drake often stands on the first-base side of the rubber, and you get a unique effect. Right-handers see the pitch boring in on them as a result of Drake’s release point, but the ball actually tails away from that path in flight, which makes for an uncomfortable swing — the ball looks like it will hit you and yet often ends up over the middle of the plate.

Repeating such unique mechanics must be difficult, and it’s a lock that no pitching coach would have taught it quite this way. The resulting pitch is weird, nearly all rise with no run, but the cost of such odd mechanics is that Drake struggled to generate velocity.

Struggled, that is, until this year. Fresh off of four straight seasons averaging between 90.3 and 92.5 mph, Drake buckled down and added 1.1 mph to the 92.5-mph average that had been his previous career high. He now sits 93-94 and touches 96, which leaves the pitch nearly average in its velocity among right-handed relievers. It’s most-decidedly not average when it comes to movement, and that extra velocity has turned the pitch from slowish oddity into world-beater; he gets whiffs on 32.4% of swings against the fastball, significantly higher than the 21.6% rate he managed in 2018 and now in the 96th percentile league-wide.

Of course, fastballs don’t miss bats in a vacuum. The other pitches you throw have a lot to do with it as well, and that’s another place where Drake made big changes this offseason. He’d always been a fastball/splitter pitcher, occasionally mixing in a slider or curveball but mainly living on two pitches.

The breaking balls mostly weren’t worth throwing, and he’s cut them out entirely this year. What’s more, he’s reduced the number of fastballs he throws, which means he’s throwing more splitters — way more splitters. He’s thrown 58.6% splitters so far this year, up from 40.2% last year and the second-highest rate in baseball. Only Héctor Neris throws more, and this isn’t some split-finger/changeup categorization game, either — the highest changeup rate among relievers is Tommy Kahnle’s 51.3%.

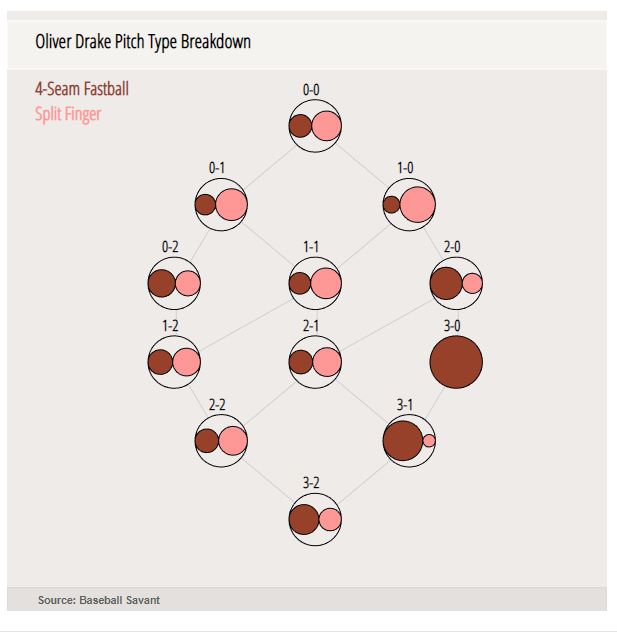

Yes, if you’re wondering what pitch is coming next from Drake, it’s probably a splitter. Short of 2-0, 3-0, and 3-1 counts though, he’s unpredictable, mixing four-seamers and split-fingers in roughly equal measure:

What’s more, the two pitches play off each other beautifully, another hallmark of modern pitch design. While the fastball is all boring action and rise, the splitter falls off the plane of the pitch and fades towards right-handers. It falls 20 inches more than his fastball over the course of its flight, and batters are slow picking it up:

Yes, that’s contact superstar Willians Astudillo waving through a pitch in the dirt. Drake will also occasionally move across the mound, creating new angles for his pitches, as he did here in locking Trey Mancini’s arms:

The multiple starting points on the mound are a new twist this year, and the extreme first-base placement in particular has been lights out against left-handed batters. His strikeout rate against lefties has gone up from 16.8% to 30.6%, while his walk rate has fallen from 7.4% to 2%. Given that he’s only faced 98 lefties, wOBA is hardly a reliable split, but he’s allowing a preposterous .165 mark to lefties, and his .227 xwOBA isn’t much worse.

It makes sense that this move would help Drake against batters who have the platoon advantage. Before this year, he stood near the third-base side of the rubber and crossfired the ball in to lefties, which gave them an excellent look at pitches that moved towards them. This year, he hasn’t thrown a single pitch from that angle, and his new placement gives batters less of a look at the ball as it comes towards them.

His arsenal has always had the potential to stymie lefties — changeups and split-finger fastballs display the lowest handedness splits of any secondary pitches. They break away from opposite-handed hitters, whereas sliders break towards their bats. Indeed, splitters thrown by righties have resulted in a .261 wOBA against lefties and .262 against righties in the last five years. Sliders thrown by righties, in contrast, allow an extra 20 points of wOBA when thrown to lefties rather than righties.

Take a bat-missing fastball and an excellent secondary pitch, sprinkle in some mound-related shenanigans to fight the platoon advantage, and you have the recipe for a pretty good pitcher. That’s just what Drake has been this year — he has the sixth-lowest FIP of any Rays reliever with 20 or more innings pitched and the third-lowest xFIP. If you want your metrics to be based on production at the plate, his .279 xwOBA allowed is fifth in the bullpen and his .264 wOBA allowed is third. He’s striking out 30.6% of opposing batters, fourth-best on the squad.

Should the Rays make the playoffs, they’ll have some difficult decisions to make about their pitching staff. Blake Snell, Yonny Chirinos, and Tyler Glasnow are all returning from injuries and two-way star Brendan McKay lurks as a potential wild card. But it would be shocking if Drake weren’t included — as a righty who can take on lefties, as a dominant reliever, and as a potential opener who has gone more than an inning in 17 appearances already this year.

That’s right — if the Rays make the World Series, it wouldn’t be a shock to see Oliver Drake throwing out the first pitch for them, taking the ball on the biggest stage in baseball. Not bad for someone who was a transactional oddity only last year and who spent the first two months of 2019 in the minors. Drake’s travels probably aren’t over — but for now, at least, they’re a journey to the playoffs, not an endless procession of hotel rooms in new home cities.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Started from the bottom now he here.