One Low-Leverage Game, Three High-Interest Situations

Here’s something you probably already knew about me, or at least inferred: I love baseball. It would be hard and unsatisfying doing this job otherwise. Here’s something you might not have known, though: I don’t actually attend that many games. I watch tons of games on TV, and I spend tons of time analyzing individual snippets, but that doesn’t leave much time to go to the ballpark, grab a seat, and take in a game.

Last Thursday, I made some time. My mom is in town visiting, and the Giants were playing the Diamondbacks in a day game — Logan Webb against Zac Gallen, two excellent pitchers facing each other in a game that didn’t have a ton of playoff implications. My wife was able to squeeze in a bit of time away from work, so the three of us got cheap seats down the left field line, bought nachos and beer, and sat down for a relaxing afternoon.

The game writ large wasn’t particularly interesting. Webb didn’t have it; he didn’t strike out a single batter, and the Diamondbacks blooped and lined their way to five runs against him. Gallen was dealing; he went 7.1 strong innings with 12 strikeouts and nary a walk. Final score: 5–0, visitors. But baseball is amazing! In that boring, snooze-worthy game, I found four fascinating individual plays to talk about. So let’s talk about them, by themselves, without any need for a connection to the season as a whole.

Carson Kelly, Savvy Baserunner?

The Diamondbacks have a ton of fast players. Kelly is not one of them. Of the 12 Diamondbacks who have recorded 50 competitive runs around the bases this year, his 25.6 ft/sec average sprint speed ranks 11th, ahead of only fellow catcher Jose Herrera. That might overstate Kelly’s speed; his home-to-first time is downright leaden, 321st of the 345 players in baseball with 50 competitive runs.

Naturally, on Wednesday he cannily stretched a single into a double. With Arizona leading 1–0, Jake McCarthy led off the top of the fourth inning with a single through the right side of the infield. Unlike Kelly, McCarthy has speed to burn. He’s not merely the fastest runner on the team; he’s one of the fastest in the majors, full stop. He’s an excellent baserunner, too, one who takes extra bases adroitly.

When Kelly slapped a grounder back up the middle, McCarthy was off like a shot. When the ball got past Brandon Crawford — not his fault at all, it was just a clean single — McCarthy put it in fifth gear and headed for third. He’s so danged fast that it was pretty much a free base, even with the ball hit to left-center. Mike Yastrzemski didn’t get the message, and went full bore after McCarthy at third:

Yastrzemski doesn’t have an outstanding arm, but he does have seven outfield assists on the year, and you don’t get seven assists by not trying to throw out the lead runner. He’s a right fielder at heart, too; the desire to show off his arm is surely always in the back of his mind. Just so we’re clear, though, I don’t think he had much of a shot at McCarthy; with the play in front of him the whole time, he knew he could round second base and hit the afterburners.

Why not go after the lead runner there? Well:

Oof, yeah, that is definitely not the way you draw it up. Evan Longoria made a heads-up play by coming off the bag and firing to second, but Kelly had gotten too much of a head start.

Little League coaches in the stands had a teachable moment for their kids. Somewhere, Keith Hernandez’s spider sense started tingling, and he was surely confused. Bad fundamentals by Yastrzemski. Good fundamentals by Longoria. Great fundamentals by Kelly. This play had a little bit of everything.

Kelly’s field awareness on the play was impressive. You can see his eyes track the play in front of him as he makes a standard turn, which turns into a full sprint (still not a particularly fast sprint, though) when he realizes what’s going on:

Again, this guy is slow. He has exactly zero career stolen bases, on zero career attempts. He’s one of the slowest runners in the majors, but you wouldn’t know it from his baserunning numbers. Sure, he hits into plenty of double plays, but if you use our UBR statistic, Kelly has been almost average in his career, with -0.8 runs worth of baserunning over 1,200 career plate appearances. That’s roughly the same as Victor Robles, and Robles is a straight-line burner with base-stealing instincts.

This stuff doesn’t really show up in box scores. It does show up on FanGraphs pages, but only if you’re really digging deep. It’s a component of WAR, but it’s hard to add or subtract much value on the bases. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t fun to watch in person, and seeing Kelly take the extra base the Giants so graciously offered him, in what for him was a meaningless August game, brought a smile to my face.

The Diamondbacks and the Anti-Shift

By the bottom of the sixth inning, the Diamondbacks had opened up a 5–0 lead. Gallen had faced the minimum number of opposing hitters; two singles were both erased by double plays. Arizona’s defense had been humming, in other words — at least when Gallen wasn’t using fastball smoke and curveball mirrors to amass strikeouts.

That defense permuted into a standard shift when Crawford led off. Up in the stands, I was only half paying attention, having just settled back into my seat with a much-needed cold beverage. But when the count got to 0–2, the middle infield started milling about, and I sat up in my seat. Were the Diamondbacks taking a page from the Giants’ book and anti-shifting?

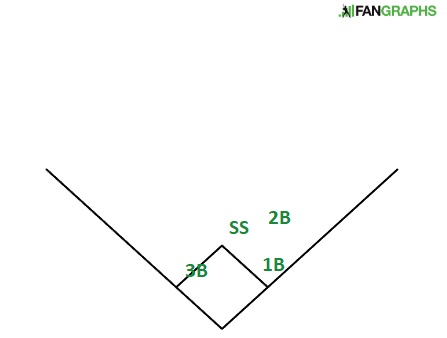

Here’s how I saw the first shift in my head:

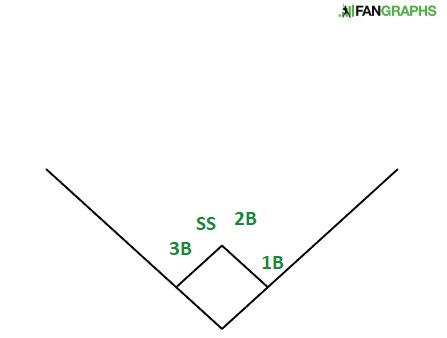

Here’s what I saw on 0–2:

I wasn’t sure I could believe my eyes, so I reached out to MLB.com’s Mike Petriello. He confirmed the change in alignment (they have alignment data for every pitch) and also pointed out that both pitches were low curveballs, which is something I’d missed in-stadium. This didn’t have anything to do with shifting the defense based on pitch selection; it was exclusively about Crawford.

If you’re a fan of baseball conventional wisdom, you’re probably nodding at your screen in appreciation right now. “Crawford shortens up and slaps the ball the other way with two strikes, like a good fundamental hitter should,” you’re probably saying. “Arizona did their homework and pulled back accordingly.”

That’s kinda weird compared to how the shift gets deployed in real games, though. Most teams actually increase their shifting with two strikes, because the old bunt-to-beat-the-shift gambit stops making sense. You don’t have to pinch your third baseman, which lets the entire defense stretch towards the pull side. Or, that’s the theory; the Diamondbacks instead bunched everyone in the middle of the field.

In this situation, the Diamondbacks did a good job going with the conventional wisdom and against the way most teams shift. Crawford hits the ball the other way more frequently with two strikes. In the past five years, his opposite-field groundball rate doubles after reaching any two-strike count:

| Count | Pull% | Straightaway% | Opposite% |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Other Counts | 47.8% | 42.8% | 9.5% |

| Two Strikes | 37.4% | 43.5% | 19.1% |

Was the shift Arizona used the perfect counter to Crawford’s tendencies? I’m not sure. It certainly looked good, and the theory feels sound to me. But we never got to find out. Remember when I mentioned the freedom that defenses have with two strikes? That was a bit of foreshadowing. Crawford wasn’t having any of that; he bunted anyway. He surely wasn’t pleased with the result:

Brandon Belt, Bunting Fool

Oh yeah, there were more bunts. The Giants were threatening in the bottom of the seventh; Longoria doubled with two outs, sending Joc Pederson to third. Belt strode to the plate with a chance to put the home team back in it; a clean single would score two, and while it’s not like a 5–2 deficit in the seventh inning is where you want to be, it’s a lot better than 5–0.

Belt has been struggling of late, and he’d looked overmatched by Gallen on the day. He’s also an avid bunter, willing to drop one down in almost any situation. The Diamondbacks didn’t respect his ability, though: third baseman Sergio Alcántara stayed back, and the rest of the infield aligned in an overshift.

It wasn’t a very good place to bunt, which explains Arizona’s relaxed defense. Unless you’re calling a squeeze bunt, which doesn’t make much sense with two outs, a bunt doesn’t always score a run here. Pederson is hardly a burner at third base; threading the needle of a bunt that could score the runner but also make Belt safe at first isn’t easy. Even then, the runner on second wouldn’t score. Lefty first baseman at the plate, righty pitcher deep in the game on the mound; it’s an extra bases kind of situation.

Belt swung away and quickly found himself in a 1–2 hole, thanks to a generous strike zone and a few nasty cutters from Gallen. Then things got silly:

I won’t delve too deeply into the math behind this one. Grant Brisbee did a great job covering the bunt already, and one of the truest definitions of madness is trying to out-write Grant Brisbee about the Giants. But I will note that I wrote this about Belt more than three years ago: “Belt hasn’t attempted a bunt with two strikes yet in his career, but at the rate he’s turning bizarre situations into bunt singles, it’s only a matter of time.”

That was supposed to be a joke. I didn’t actually think he was going to run a two-strike bunt, particularly with runners in scoring position. Belt’s explanation was that he thought it was his best chance of reaching base against a cruising Gallen. This is more common than you’d expect. There have been 23 foul bunts with two strikes this year. There have been 47 attempts overall, which means just over half have at least put the ball in play. Heck, this was Belt’s third time this year trying it, and second time in August.

The first time worked perfectly:

The second time, not so much:

But at least that one required a tough play from a solid defender. Belt’s heart might have been in the right place last Thursday, but his execution certainly wasn’t. He drew a smattering of boos as he left the field, and while I’m no fan of bunt shaming, even I thought this one went too far. Gallen couldn’t believe his good fortune:

Belt has always been DTB (down to bunt). In previous years, that added a splash of intrigue to his game; he was an excellent offensive first baseman who might suddenly turn any defensive lapse into a bunt single. 3–0 counts are a lot more interesting when they might end in a drag bunt. Belt brought a welcome hint of chaos to a game that can at times feel too orderly.

It’s not quite so fun when he’s struggling with the rest of his game. When the bunts feel like a must rather than a may, they’re not nearly so delightful; they’re boo-worthy at times, even. That was a very relatable feeling for me, sitting out in the stands. When I have to do things, they’re a drag, a chore. When I can do them for fun on a whim, they’re just that: fun. Major leaguers: they’re just like us, for some specific definition of “just like us.”

I could go on about this game. I haven’t even talked about Daulton Varsho taking off from third base for home because he thought time hadn’t been called; he made it all the way to the dugout and stayed there quite a while before the umpires could sort out what was happening. I could talk about Pederson making 90% of a good defensive play before letting the ball clang off his glove, or about him making a subsequent great defensive play and tumbling head over heels to the ground afterwards, the bottoms of his bright green cleats glinting in air.

None of these needed larger context to capture my interest. Sure, baseball is great because of its connection to the past, but it’s also great because you can go to any random game and find fascinating decisions and strategies to ponder. I love that about the game. I also love that you could also go to the same game I did, sit in the same section I did, and not care about any of this. You’d still have fun! The weather was perfect, the scenery was idyllic as always, and the sounds of baseball work wonders as a stress reliever. What a wonderful sport, whether in person, or analyzed in retrospect.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

I’m Ben’s Mom and it certainly was a wonderful day at the ballpark!