Patrick Corbin Slows the Tempo

In my mind, Patrick Corbin is an archetype. He’s the idealized sinker/slider guy, pairing the two pitches so masterfully that batters can’t figure out which one is coming until it’s too late. His breakout in 2018 was foreshadowed by a solid 2017, when he upped the percentage of sliders he threw from 26.5% to 38%, and he hasn’t looked back since. After signing with the Nationals as a free agent, he’s delivered another solid season, sinking and sliding his opponents into oblivion, with a few four-seamers thrown in to keep batters honest.

That’s not all he does, though. That’s the business side of Patrick Corbin’s pitching, but sometimes he likes to goof around. Take a look at this ludicrous curveball he threw Manny Machado in June:

That is absolutely nothing like every other pitch Corbin throws. Machado’s not even mad; he’s impressed:

Yes, Patrick Corbin has a slow curve, and it’s a joy to watch.

The slow curve is an endangered species these days. Modern baseball prioritizes faster, sharper breaking balls. As recently as 2008, there were 6,470 breaking balls below 70 mph thrown in the major leagues. Last year, there were only 1,112. This year there have been 1,001, which puts us on pace for 1,276. That would be the second-lowest number of slow curves thrown since we have velocity data.

Despite that decline, some pitchers are slow curve devotees. Corbin’s former teammate Zack Greinke has thrown a slow curve since he came into the majors, averaging 77 a year since 2008. Mark Buehrle went to a slow curve throughout his career. If you learn the pitch young, you might be tempted to stick with it in the bigs.

Patrick Corbin is emphatically not that. He’s pitched in the major leagues since 2012, and the first pitch he threw below 70 mph was in 2018. It wasn’t a planned thing, even — he just decided to do it one day. “I think I made up a pitch today, just threw a pitch at 65 (mph),” he told reporters after a mid-April start. “I’ve never done that. I’m not sure where that came from.”

In that start, he mostly threw the slow curveball out of the zone. Batters weren’t ready for it, and often ended up looking silly:

As Jeff Sullivan pointed out last offseason, the pitch is more of a slow slider than a true curveball — it has nearly the same horizontal and vertical break before gravity as his slider does. The differentiating factor is the speed — with more time to fall, the curve fell 10 inches more than the slider in 2018, and is falling 17 inches more so far in 2019.

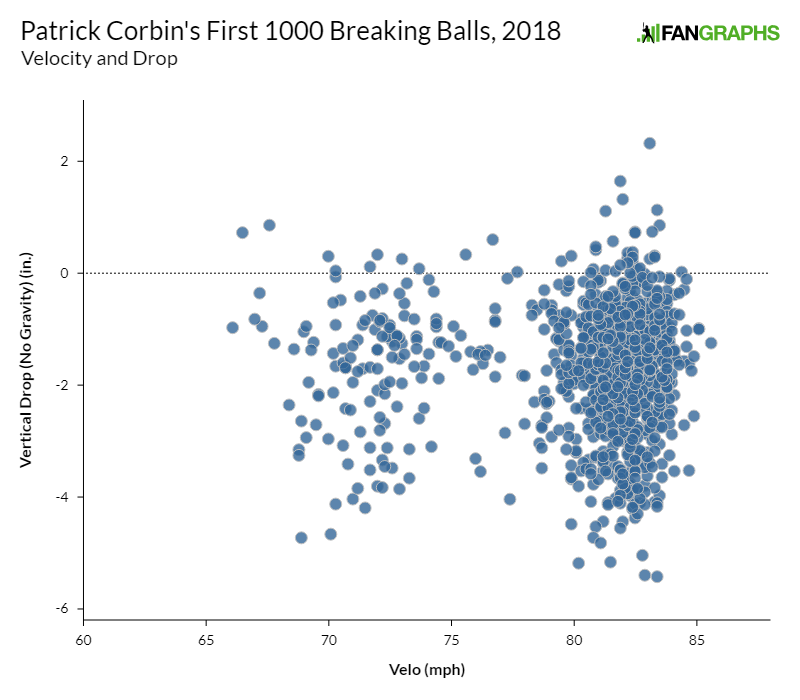

Where have the extra seven inches of drop come from? The curveball has slowed down even more this year. Last year’s pitch averaged 72.8 mph, and some of the fastest curves blended with the slowest sliders in a kind of velocity soup. Here are the first thousand breaking balls Corbin threw last year, the most I could throw into our graphing tool:

There was some cross-classification in the middle — how could there not be given how seamlessly the pitches blend? This year, though, Corbin has differentiated the two. His average curve velocity has fallen to 68.2 mph, and the 70-80 mph range is much less cluttered:

Which is better from a pitching standpoint? I honestly don’t know. There’s something to be said for throwing a great big blend of pitches that overlap, constantly messing with timing and location and making life confusing for the batter. Félix Hernández was one of the best pitchers in baseball for years by blending everything, and Greinke succeeds today using that method.

From a viewing perspective, though, the separated pitches are far better. I don’t want to see Corbin take a tick off of his slider and tuck the ball just past where the batter thought it was headed. I want hilarious, mind-bending hooks that look like they’re headed for the upper deck before dipping into the zone. I want it to look like Bugs Bunny is out there on the mound. I want this:

That’s Pablo Sandoval, one of the freest swingers in baseball. 67 mph right down main street? He still can’t bring himself to swing, because how could that ball fall so much?

When a slow curve is working, it’s like magic. It’s not the kind of pitch a pitcher can break out frequently, though: the reason it works so well is because batters are gearing up for sliders and fastballs. When they see this pitch, they either think slider and swing too early and too high, or get confused and don’t even swing. When batters know what’s coming, or simply time it up right, it turns from comedy to tragedy:

Corbin seems to understand this well. He’s thrown the curve sparingly this year, only 4% of the time. He never throws it on two strike counts, when batters are primed to swing. This isn’t a hyperbolic never, either — he only uses it in 0-0, 0-1, 1-0, or 1-1 counts.

You might think that the pitch can’t be that valuable if it never strikes anyone out and almost never gets used. You’d be right — by pitch values, it’s added almost no value this year. It gets a called strike, swinging strike, or foul ball about half of the time, which is solid, but it’s certainly not what’s driving Corbin’s excellent season.

That doesn’t mean it doesn’t help, though. The next pitch to Sandoval induced a lazy fly ball on a fastball Sandoval was clearly late on. Machado? He topped a fastball into the ground for an easy out. We don’t yet have a great way of describing how pitches combine together, and we may never fully quantify it, but throwing a slow curveball like Corbin’s seem to do something to batters.

Batters swing 66% of the time the pitch after a slow curve, 44% of the time at pitches out of the zone. That beats his normal chase rate, both overall and after adjusting for the count. They’ve recorded only three hits, two singles and a double, out of 48 swings, and 14 outs. It’s hard to prove value in these things, but it certainly seems like batters perform worse in the pitch following one of these great sweeping hooks.

That’s all well and good, and we could go on theorizing exactly how much value Corbin gets out of the pitch, but the truth is that I don’t really care. As long as Corbin feels like throwing the pitch, I’m a winner. You don’t need advanced metrics or complex analytics to laugh when this happens:

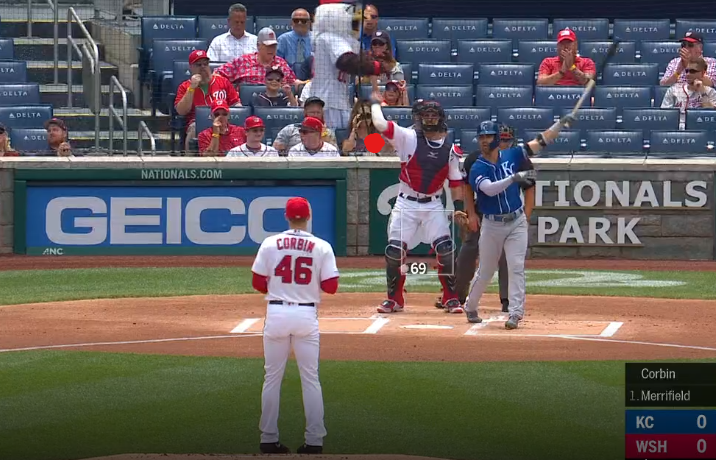

How ludicrous is that break? If you account for the effects of gravity, Corbin’s slow curve falls 40 inches more than his average fastball. We’re approximating a little, but it’s easy to find strike zone top and bottom measurements for Whit Merrifield, and it’s 21 inches tall, which means that a fastball thrown on the same initial trajectory would have ended up roughly here:

At the end of the day, I can’t say conclusively whether Corbin’s slow curveball adds any value for him. I can say, however, that it’s added a lot of value for me. When I watch a Corbin start, I get to see what a star starting pitcher looks like, and then four or five times a game I also get to see a parlor trick designed to delight and amuse.

What’s Patrick Corbin’s ERA this year? I didn’t know the exact number until looking it up — an excellent 3.17. Was he an All-Star? I had to look that up too — he wasn’t, though not for lack of merit. My point is that we won’t remember the exact details of Corbin’s 2019 in a few years, barring some postseason heroics. I’ll remember the slow curve, though. Baseball could use more questionably effective but aesthetically beautiful pitches.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

I’m in full agreement. I don’t care if the pitch doesn’t technically add value to Corbin’s arsenal. It adds value to my viewing. I love it when pitchers can break out these kind of extreme off-speed pitches and make batters look silly.