Pete Alonso, Corey Dickerson, and Two Dissimilar Power Outages

Pete Alonso didn’t duplicate his stellar rookie season in 2020. There wasn’t one obvious problem to point to, though. He trimmed his strikeouts slightly. He hit the ball as hard, both in frequency and in terms of maximum exit velocity, as he did the year before. He made more contact in the strike zone, and he swung less at pitches outside the strike zone. That all sounds pretty good.

Despite all those glowing facts, there’s no way around it: Alonso was a lot worse in 2020. His BABIP dropped from .280 to .242. His slugging percentage fell by nearly 100 points. He fell off of his 2019 home run pace, but not by as much as you’d think. He lost far more doubles, though, and didn’t make up for it elsewhere. He wasn’t bad, but a 118 wRC+ out of your bat-first first baseman is par for the course rather than spectacular.

What if I told you I could explain what went haywire? You’d probably tell me I’m lying, and you wouldn’t be wrong. I can tell you what I think happened, though, and that will have to be good enough. You know how I said his contact was just as loud? It’s time to delve obnoxiously deep into that data.

Alonso’s swing is tailored for maximum damage. When he hits the ball hard, he puts it in the air. In 2019, the hardest 5% of balls he hit left his bat with an average launch angle of 14.5 degrees. That’s great, though a little higher would be even better. In 2020, those same hardest 5% of balls were, indeed, higher — 23 degrees, to be precise. For the rest of this article, we’ll call the average launch angle of that subset of balls his peak-power launch angle.

What does that look like in a game? Like this:

Or this:

That’s what he’s trying to do every time he’s up at the plate. It’s exactly what you’re supposed to do; tailor your swing so that when you connect most squarely, you’re putting it in the air. The 20-to-30 degree area is where you want your best contact to live, but a touch lower than that works fine as well. The key is to get the ball in the air without popping it up — doing so is where homers and doubles come from.

If we know where Alonso generated his hardest-hit contact, it follows that the more he can replicate that swing, the more he can take a leisurely trot around the bases, or at least smash something into the gap for a double. In 2019, 15% of Alonso’s batted balls left his bat at an angle within five degrees of his peak-power launch angle. That’s a stat mouthful, but you can roughly think of it as saying that 15% of the time, he hit the ball the way he needs to to generate the most raw power.

That number won’t make a ton of sense without context, so let’s provide some. As a whole, hitters posted a 14.5% mark in 2019 (14.4% in 2020). Launch angle variation is inevitable — everyone hits grounders, line drives, fly balls, and pop ups (even Joey Votto these days). For batters overall, 15-ish percent of their contact looks roughly similar, at least when it comes to the angle at which it leaves their bat, to their best contact.

Alonso wasn’t a standout in this area, but you don’t need to stand out at everything. His best traits stem from his sheer physical might; his maximum exit velocity is right there at the top of the league, and he absolutely scalds the ball. All it took to convert that raw power to game power was executing his best swing at a league average rate.

In 2020, things didn’t work out nearly as well. You might think, on first glance, that getting his hardest-hit balls higher in the air would be a positive development. It was — for those hardest-hit balls. On the other hand, he didn’t repeat that swing all that often. Only 7.6% of his batted balls were within five degrees of his peak-power launch angle, the worst mark among anyone with 100 batted balls in 2020.

I can hear your objections already. What if that 23-degree mark in 2020 is measuring the wrong thing? Maybe his true best swing stuck right around 15 degrees. Approximating a best swing based on hardest-hit balls does have its downfalls, after all.

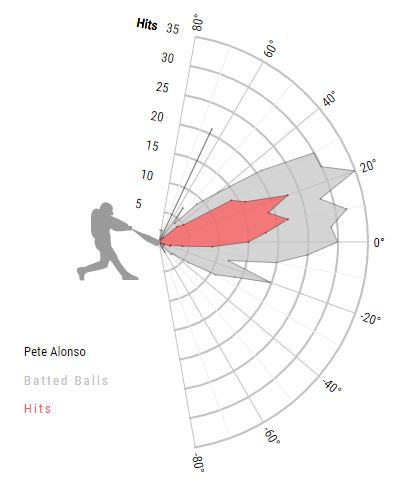

Bad news, Alonso backers. He also only put 9% of his 2020 batted balls within five degrees of his 2019 peak-power launch angle. Take a look at it in Baseball Savant form, and it quickly becomes obvious. Here’s 2019:

That’s a delicious-looking chart. Look at all those high-value batted balls. Next, 2020:

Oof. Those grounders aren’t doing anything good.

You might argue that I’m measuring something like launch angle consistency with this. It’s certainly somewhat similar to that. Fail to repeat your swing, and you’ll decline in both metrics. Alonso’s launch angle standard deviation went up from 2019 to 2020, for example. But looking at peak-power launch angle and consistency does something else, too.

Consider the case of Corey Dickerson. He had a down year in 2020; his .258/.311/.402 batting line worked out to his worst wRC+ since his rookie year. The culprit? A marked decline in power. His .144 ISO was the lowest of his career by 31 points. Here’s the weird thing: if you only look at the percentage of his batted balls hit near his peak-power launch angle, he looks great!

In 2020, Dickerson hit a full 20% of his batted balls within five degrees of where he hit the ball hardest. That’s the third-highest mark among batters with at least 100 batted balls. Just one problem: that peak angle was 4.7 degrees, something between a grounder and a line drive. This is a nice piece of hitting — but it’s also his hardest-hit ball of the year, and it was only a single:

The advice you’d give Dickerson would be completely different from what you’d tell Alonso. In Alonso’s case, his ticket to success is to replicate his best swing more often. That’s easier said than done, of course, but the thing that went wrong is at least straightforward. Alonso’s best still works; he just needs to do it more often. With Dickerson, the problem is something else entirely. In 2019, Dickerson’s peak power came at an average of 15 degrees. That’s great, and he was consistent at it too: 19% of his batted balls came within five degrees of that peak angle. If you think of him as a guy who sprays line drives around the park, you’re picturing him in 2019.

Dickerson’s ticket to improvement, then, is getting the ball back in the air. Plenty of other metrics could tell you this — his GB/FB ratio spiked to the highest of his career, his line drive rate fell to the lowest of his career, and he recorded fewer barrels per batted ball than he ever had. It’s not like you have to look hard to find reasons he wasn’t good in 2020.

But “your hardest-hit balls are on the ground and that’s bad” is a better piece of feedback than “stop hitting grounders.” From 2015 to 2019, 37% of the balls he hit at 100 mph or more were hit at 10 degrees or lower. In 2020, that number spiked to 62%. The lower peak-power launch angle is picking up this change. Dickerson’s highest impact came at a flatter angle, and his production paid the price.

Alonso and Dickerson both suffered power outages in 2020. How would I fix this? I’m not a hitting coach, so I can’t tell you. Knowing what went wrong is half the battle, though, and looking at where you hit the ball hardest can tell you something that you might otherwise miss.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

I’m sending this to Sandy Alderson.

I’m confident they know this already. Pete’s going to have a big bounce back year. If not, Dom Smith will get the playing time. Good problem to have

@Jeff in Jersey No, seriously.

The Mets still haven’t filled half the jobs in their analytics department. Until Alderson departs the Mets will continue to blunder around much as they did during the 2010s during Alderson’s first tenure. The only difference now is that as with the Wilpons pre-Madoff, money will paper over a lot of holes.