Pete Alonso is Hitting Into the Winds of Fate

At the end of August, the Philadelphia Inquirer suggested that Mets rookie sensation Pete Alonso and Phillies first baseman Rhys Hoskins could be the next generation’s greatest player rivalry in the NL East. At that point, Alonso was slugging a hundred points higher than Hoskins and had almost 20 more home runs on the season. Unlike Alonso, Hoskins regularly slips away from the Phillies lineup, disappearing for weeks at a time: There’s streaky, there’s bad luck, and then there’s hitting under .230 in the clean-up spot for three months.

Meanwhile, Alonso broke the Mets’ single-season home run record on the first pitch he saw against Yu Darvish on August 27. If all Alonso had done was break the record, the only history we’d have to mention is from the recent past: Carlos Beltran and Todd Hundley held the previous Mets record, 41, having set it in 2006 and 1996, respectively. But because of Alonso’s rookie status, his accomplishment is made even more distinct.

You only get one season to set rookie records — or set records as a rookie — and through that slim window, Alonso has slipped his 6-foot-3, 245-pound frame. This is due in part to his classification by baseball scientists as a “pure hitter.” Determining what is meant by this term usually leads to a loudly shouted or frantically typed mention of historic figures like Ted Williams or Joe DiMaggio. The eyes of baseball puritans light up when talk begins of Alonso “pure-hitting” like sluggers did back in the good old days, when pure-hitting was America’s pastime, along with losing everything on the stock market and the rampant abuse of benzedrine.

Anyone who has swung a bat can tell you what a pure hit feels like: when timing, mechanics, and strength align to allow the barrel of the bat to connect with the sweet spot of the ball. But being a pure hitter means doing all that more than once. To make the impression of a Pete Alonso, you’ve got to keep doing it within the span of one season — your first season facing big-league pitching. Alonso is doing just that, and you have to go back pretty far to the find the last guy who did: Johnny Rizzo, in 1938 for the Pirates — a man who gives us a historical post to which we can tie Alonso’s accomplishments, while also viewing them through the filter of… well, being on the Mets.

Rizzo was the biggest new addition to the Pirates in 1938, inheriting a spot in Pittsburgh’s outfield from Woody Jensen next to the Waner brothers, Paul and Lloyd, nicknamed Big Poison and Little Poison. Rizzo appeared to be the antidote to the Pirates’ offense, hitting .301 as a 25-year-old starter in 1938 while slugging .514, as well as having a particularly voracious appetite for lefties, against whom he hit .339 with a 1.006 OPS.

“I am going to be the Joe DiMaggio of the National League,” Rizzo assured Pirates management in a letter he included with his signed contract before the 1938 season, as reported in The Pittsburgh Press, on September 3, 1938.

Not only did he seem primed to become that purest of pure hitters in the AL, but Rizzo was a team player too, ready to get fans fired up in the name of baseball justice. In Pennant Hopes Dashed by the Homer in the Gloamin’: The Story of How the 1938 Pittsburgh Pirates Blew the National League Pennant, Ronald T. Waldo relays the story of how during one game that season, Rizzo was ejected for arguing a third strike call on one of his teammates, got fined $25 for running out of the dugout, and then came back the next day and crushed a three-run home run.

Like the Mets of today, the Pirates that had preceded Rizzo’s rookie season were known for inevitable failure, regardless of any earlier success. Sportswriter Sid Feder blamed manager Pie Traynor for Pittsburgh’s rough patch coming even earlier than usual in 1938, claiming that Traynor had failed to give his team “that extra little jolt of motivation in the spring” that could carry their early season hot streak into May3. As the Pirates stumbled that month, so did Rizzo, putting together his worst offensive stretch of the season: a slash line of .239/.307/.315, though his .244 BABIP indicated this was an outlier.

This season, Alonso also had a month-long stumble, back in July when it looked like the magic was gone. He hit .177 that month, but the thing was, nobody talked about it. His appearance in the All-Star Game and the Home Run Derby overshadowed any problems at the plate, as did an unsolicited issued assurance to Mets fans that “The rest of the season is going to be really fun, wild, and a memorable ride.”

And why shouldn’t they have believed him? The team pulled in Marcus Stroman at the deadline and didn’t trade Noah Syndergaard. They broke off an eight-game win streak (during which Alonso purely slugged .769 with his own four-game homer streak) and re-entered the playoff picture, just as Brodie Van Wagenen had foreseen in the prophetic texts he discovered in an abandoned chop shop outside Citi Field in the off-season, flooded with ankle-deep sewage.

But when a Mets fan feels joy, they often have to wonder: Is that happiness I’m feeling, or disease coursing through my veins from a fresh rat bite? Alonso convinced a fanbase deadened from repeated trauma that he was going to make everything okay — and they had to believe him. He should get a trophy for that alone.

Everything Alonso has done — the .391 wOBA, the near 30% HR/FB rate, the smiles on the faces of Mets fans — has been made more incredible by the fact that he is a rookie while he does it. He is nearing the end of the one year that allows him to break records that will be inaccessible to him in all of the years that follow. He shocked a dead team back to life and brought their fans back into the season, and sometimes, it looks like he’s doing it all by himself.

Just like the last guy.

In 1938, the Pirates led the Cubs in the standings by half a game on September 27, having wedged themselves into the lead in mid-July and clung dearly to the top of the heap ever since. Then they lost six of their last seven games — three by one run — all while Rizzo desperately slugged .655 in his last 29 at-bats of the season. It wound up all for nothing, especially in their last game, when he went 4-for-5 with one last two-run shot fired into the seats at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, as if to say, damn it, I tried.

“Rookie Johnny Rizzo came through with a bang and almost won a pennant single-handed,” wrote Paul Scheffels for United Press on October 31, 1938, “but Pie Traynor, who had more pitchers than any other club, would have given his last dollar for one that could win ‘going away’ in those last few exciting days.”

Rizzo’s slump started in 1939 and continued into 1940, and when slumps get that long, you seem to lose your purity as a hitter — though Rizzo did do things like knocking in nine runs in a single game, a Pirates record that has held fast for 70 years. Still, he never found that level of success again, destined to not be a commonly uttered baseball name until Alonso’s heroics stirred him out of the past.

Alonso’s impressively powerful 2019 has been fun to watch, and unlike Rizzo, his future is entirely ahead of him. But last Tuesday night, that future turned into another twisted inning in the Mets’ fractured history.

Alonso led the Mets offense with three hits against Washington that night, scoring twice and knocking in two runs. In the ninth inning, a Mets rally was permitted to continue when Nationals shortstop Trea Turner forgot how many outs there were and didn’t go for an inning-ending double play. This allowed Alonso to come up one batter later and finish his night at the plate with a two-run shot fired into the seats of Nationals Park. It gave the Mets a 10-4 lead that seemed quite secure heading into the bottom of the inning.

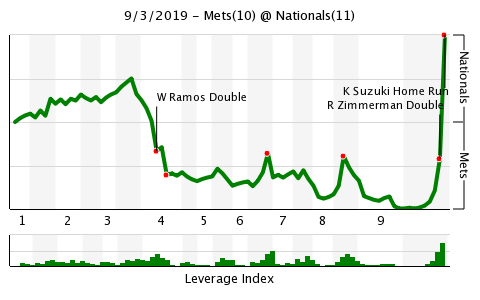

Here’s damn it, I tried in graph form:

The game is always finding new ways to twist a rookie’s narrative. On Friday, Alonso was getting his jersey ripped off in celebration of a walk-0ff walk (why beat the other team when you can simply let them lose to you); on Sunday, he was striking out on a foul tip with a runner in scoring position and a series on the line. In less than a year, he will transform from an exciting rookie to a sophomore with high and deep expectations; expectations that can land with some regularity as far as 440 feet away. This initial introduction to the sport has been thrilling and awesome and occasionally shirtless, but probably, too, unfairly definitive. Hoskins had a hell of a record-breaking rookie campaign himself and is still working out what kind of hitter he is.

Is Pete Alonso Johnny Rizzo? No. A couple of comparative stretches don’t seal anybody’s fate, especially somebody who has shown the terrifying power of Alonso. But when you’re a rookie, there’s not as much behind you to taint the purity of your swing. All that matters in 2019 is that he’s a big guy who smashes more homers than anybody, and he’s brought a little joy to some people from whom it’s much more often snatched away.

For a moment, maybe that’s hitting at its purest.

Pete Alonso just crushed home run No. 44 to straightaway center field. Chants of "M-V-P!" ring out from a very pro-Mets crowd here at Nationals Park.

Mets 10, Nationals 4, top ninth. pic.twitter.com/f1iiRHPv0E

— Anthony DiComo (@AnthonyDiComo) September 4, 2019

Justin has contributed to FanGraphs and is a contributor to Baseball Prospectus. He is known in his family for jamming free hot dogs in his pockets during an off-season tour of Veterans Stadium and eating them on the car ride home.

I don’t quite follow how Pete Alonso is similar to Johnny Rizzo.

“Is Pete Alonso Johnny Rizzo? No. A couple of comparative stretches don’t seal anybody’s fate, especially somebody who has shown the terrifying power of Alonso. “

Agreed. I was waiting for the “Alonso is the first player since Rizzo in ’38 to have Y stats in his rookie year.” But it never came. Rizzo is just vaguely referenced as the last rookie who showed himself to be a pure hitter, which is frankly pretty hilarious, since Ted Williams broke in as a rookie the very next year..

Agreed. “Alonso is doing just that, and you have to go back pretty far to the find the last guy who did” – Exactly what is THAT? It’s not at all clear. I suspect THAT = set your franchise’s all-time single-season HR record as a rookie. That Rizzo’s 23 in 1938 was the new record for the Pirates. But it’s not very clear.

I’m not a native speaker and while it isn’t directly stated, it’s pretty clear to me what the writer meant.