Chance Adams, Domingo German, and Nick Pivetta on Developing Their Curveballs

Pitchers learn and develop different pitches, and they do so at varying stages of their lives. It might be a curveball in high school, a cutter in college, or a changeup in A-ball. Sometimes the addition or refinement is a natural progression — graduating from Pitching 101 to advanced course work — and often it’s a matter of necessity. In order to get hitters out as the quality of competition improves, a pitcher needs to optimize his repertoire.

In this installment of the series, we’ll hear from three pitchers — Chance Adams, Domingo German, and Nick Pivetta — on how they learned and developed their curveballs.

———

Chance Adams, New York Yankees

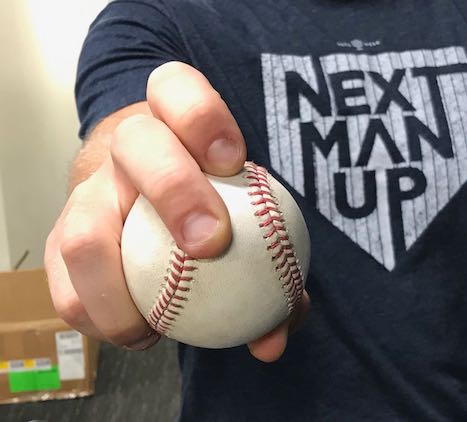

“When I was in college my pitching coach was Wes Johnson, who is now with the Twins. He taught me my curve. For awhile it was kind of slurve-slider, then it went to a curveball, and now it’s kind of slurvy again. But it’s interesting, because when I got [to Dallas Baptist University] it was, ‘OK, I throw it like this,’ and he was like, ‘Well, have you tried spiking it?’ My curve was moving, but it wasn’t sharp, and I was like, ‘No, not really.’ Spiking it was uncomfortable at first, but after I got used to it, it was pretty interesting. It started moving better.

“My pointer finger is off the seam, with just a little pressure on the ball. Wes said to try spiking it and see what feels good, so I worked on it with this much spike, that much spike. Even now, the spike kind of varies for me; I’ll move it back or forward for comfortability, but also movement-wise. Sometimes it’s sharper when it’s more spiked. It kind of depends on the day, and if I’m controlling it or not.

“If I’m throwing a few balls, sometimes it’s, ‘OK, let’s chill on the spike a little bit and get this for a strike.’ The curveball is supposed to be kind a strike pitch for me, and the difference is where my finger is touching it. I’ll move my [pointer] finger forward, just slightly, with maybe more of the pad on the ball — it’s flatter — as opposed to being back a little more and more spiked. Either way, my thumb is underneath on a seam. I like it on a seam.

“I guess the spiking is kind of funky, but other than that, I don’t throw anything too crazy out there, grip-wise. Even with moving it around on the ball. They tell me that there’s not really a big difference [in movement] when I do. Again, I’m doing it more for comfortability and getting a strike. I’m not doing it for more spin, or anything; I just want to get a strike.”

Domingo German, New York Yankees

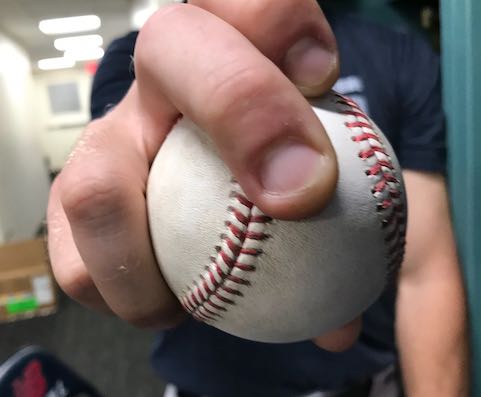

“Playing Little League, and stuff like that, you kind of play everywhere. I did a little bit of pitching then, but mostly I was at other positions. So I’d say that I learned a curveball when I was around 15 years old. The man who taught it to me was Alex Martinez, the scout who signed me. He showed me a grip. A couple of months later he saw me again and by that time I had gotten more comfortable with the spin. It’s the same grip now that I learned when I was 15.

“It’s a different kind of grip from a traditional curveball. I spoke to [Masahiro] Tanaka and [J.A.] Happ, and they tell me it’s a different grip. They tell me that when my curveball breaks, it breaks down hard. And even Gary [Sanchez] tells me that sometimes it’s hard blocking it, because when it bounces it’s not like every other breaking pitch. When it hits the floor it just goes in a different direction. I guess the grip and the rotation have something to do with that. And when I show the other guys, it kind of takes them a little bit to understand the grip. They tell me it’s kind of hard to do it.

“I wouldn’t say that my curveball is just God-given talent. There has been a lot of work. The one thing I can say is that from the beginning… it felt like it took me a long time to get the right timing on it, and the right release point on it. I’ve always liked to feel the stitches on my hand — around the palm of my hand — and also feel the grip on the middle finger. It gives me a better hold, a better grip, and that really allows me to pull down on it and get more rotation.

“It’s the same curveball all the time. It’s just that not every outing is going to be the same. Some days your velocity might fluctuate a little bit; your fastball might be a little higher, therefore your curveball might be a little higher too. And vice versa. But overall it’s the same curveball. It’s just commanding it at different locations. If I’m going for strike-one with the curveball I try to execute strike-one — but it’s still the same curveball. If I’m trying to put away a guy, I execute the same pitch with a different release point. It’s a lower release point.

“Is it a power curveball? I don’t know if I can call it that myself, but from what other people have told me… like what I mentioned before, Happ tells me how much it breaks down. I guess you can call it a power curveball.”

Nick Pivetta, Philadelphia Phillies

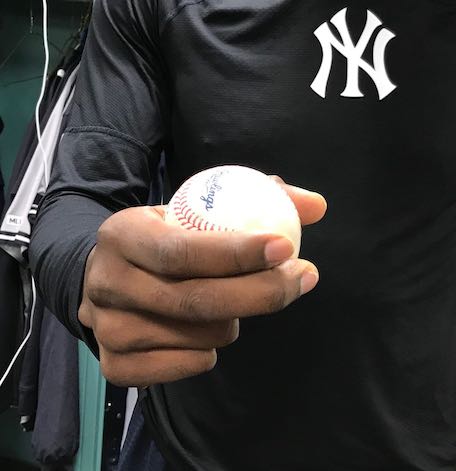

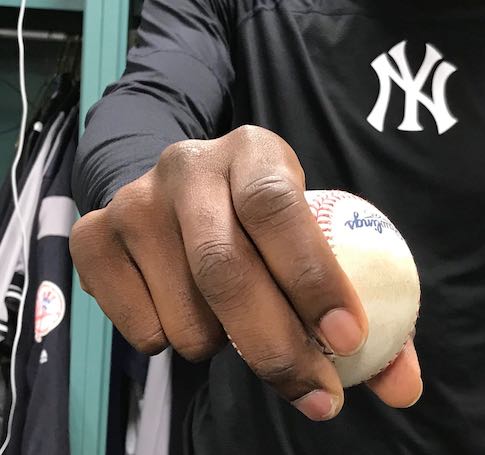

“I got called up to the big leagues in 2017. Bob McClure was our pitching coach. He looks at me and goes, ‘Hey, throw your curveball like this.’ It was my first week in the big leagues and he showed me this spiked grip. He said Aaron Nola is throwing it. So I did, and it was a natural pitch for me. It broke the same every single time, and had really good rotation. This was after my first start, and I learned it within the first week. Before I’d thrown a traditional two-finger curveball.

“When [McClure] made the suggestion, what I thought was, ‘This guy pitched in the big leagues for 15 seasons; I’m going to listen to him.’ I was young, I was curious, and wanted to learn. I’m always open to trying new things, learning new things. I’m not ever going to shut anybody down if they’re willing to help me. If it works it works, and if it doesn’t it doesn’t. It’s a grain of salt. Everything is a grain of salt. I just know it worked really well and has been a really good pitch for me ever since.

“Why [does it work better than his old curveball]? That’s an interesting question. I think lot of it is the science of it. But really, I think it’s the way the ball is pressured. I use it on my pointer nail. I lock it in and have all my pressure on these two fingers. I’ve always been able to spin the ball naturally and this gives me more pressure on the pitch, and allows me to spin it more. I have more extreme downward tilt to it.

“A curveball I’ve always liked is Brandon Morrow’s. I grew up watching him, because I used to watch the Toronto Blue Jays. He had a devastating curveball, right? That’s what I try to picture when I’m throwing mine. I think my spin averages 3,000 [rpm], or maybe a little less. I don’t know what it was on my old one. I don’t think the Phillies used that type technology until more recently. It was mostly last year when I learned more about rotations. I also can’t tell you exactly how much more it moves, but I do know that it’s a way-more elite pitch than my old curveball.”

——

The 2018 installments of this series can be found here.

David Laurila grew up in Michigan's Upper Peninsula and now writes about baseball from his home in Cambridge, Mass. He authored the Prospectus Q&A series at Baseball Prospectus from December 2006-May 2011 before being claimed off waivers by FanGraphs. He can be followed on Twitter @DavidLaurilaQA.

This is terrific content. Great stuff, David.