Reports of Kyle Seager’s Decline Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

If you follow baseball from the East Coast, it’s easy to forget about Kyle Seager. Though never quite as famous as his performance would merit, he’s been a star for the better part of the last decade — he and Félix Hernández were the solitary workhorses trying to drag the Mariners out of a playoff drought and back to glory. Seager arrived in the majors at the tail end of Félix’s peak, but they were both always there, annually among the game’s best and never in the playoffs.

That feels like eons ago now. The Mariners have been redefined since then; by Jerry Dipoto’s manic trading, by the delight of watching Daniel Vogelbach hit, by painful injuries and eagles landing. Meanwhile, time has dragged the old generation down. With Félix’s rapid decline as a guidepost, it’s easy to lump Seager in with him as a deprecated model of Mariner.

The numbers tell the story. From 2012 to 2016, Seager posted a wRC+ between 108 and 134 every season and averaged 4.5 WAR per year. He seemed to only be getting better — 2016 was his best season yet, a 5.2 WAR, 134 wRC+ masterpiece when he struck out only 16% of the time and walked at a 10.2% clip. A down 2017 (106 wRC+) was understandable, with a low BABIP and slightly worsening plate discipline dragging down his overall line, but a downward trajectory for a 29-year-old was enough to make observers a little worried.

2018 was worse — his walks plummeted, his strikeouts ballooned to 21.9%, and he posted a lower ISO than he had in dead-ball 2014 on his way to an 83 wRC+. He started 2019 on the injured list after hand surgery, a worrisome injury for any hitter. It was slow going upon his return, and as the Mariners wilted after their strong start, it felt as though Seager’s career was doing the same.

After 163 first-half plate appearances, it looked as though 2018 was a harbinger of things to come — Seager’s .203/.288/.371 line added up to a 77 wRC+, with an isolated power even lower than in 2018. Vogelbach was raking, Domingo Santana was doing exciting things, and J.P. Crawford looked to be acclimating well to the big leagues at long last. Seager felt like an afterthought on the team, a ghost of the past stuck in a changing present.

Yeah, about that. Kyle Seager has been one of the best players in baseball, full stop, in the second half. His anemic start is all but forgotten, as he’s slashed .293/.366/.626 on the way to a 160 wRC+ and a whopping 2.5 WAR in only 47 games. His season-long line now works out to a 122 wRC+, which would be the third-best of his illustrious career, and only his curtailed playing time will keep 2019 from being one of his best years.

Where did our brains go so wrong in expecting Seager to fade into oblivion? How did he rejuvenate himself so thoroughly and suddenly? It’s a question worth investigating. First of all, the bad 2018 wasn’t reflective of Seager’s true talent level. Everyone has a down year from time to time. Seager’s merely confirmed narratives already bouncing around in people’s heads: that the old guard of Mariners players had been replaced, that age comes for stars earlier and earlier, that Seager’s game was never meant to last.

In fact, players have bad seasons all the time without it being a sign of doom. Steamer projected Seager for a 105 wRC+, with ZiPS in the same neighborhood, before the season. Both expected reduced playing time due to his injury and age, but the numbers worked out to a roughly 3 WAR per 600 PA pace, a strong recovery from 2018. It’s easy to get carried away, but sober analysis expected an above-average 2019 all along.

But Seager’s second half hasn’t been just above-average. It’s been downright torrid, the kind of performance that wouldn’t look out of place from an MVP contender. It hasn’t been a fluky, BABIP-fueled explosion — his .300 BABIP is better than his career average, but it’s nothing special, nothing that says this couldn’t continue. Nor has he ridden a boatload of walks, intentional or otherwise, to his lofty batting line. He hasn’t been walked intentionally at all this year, and his 9.6% second-half walk rate is actually slightly lower than it was the first part of the year.

When a season like this happens, two explanations often get bandied about. First, there’s regression to the mean. This oft-misunderstood concept refers to the fact that regardless of past performance, future performance will be distributed randomly around a player’s mean outcome, which means that extreme first-half performances tend to give way to less extreme full-season lines on the back of more reasonable second halves. It most explicitly doesn’t say that just because Kyle Seager was bad in the first half, he should be amazing in the second half.

If it’s not regression to the mean (and seriously, it’s not! Don’t use regression this way!), could it just be that enlightened cousin of regression, random variance? After all, Kyle Seager is a good hitter, and good hitters will naturally have hot and cold streaks without anything being amiss. Craig Edwards investigated this exact phenomenon when it comes to Nicholas Castellanos and found that a hot month or two isn’t out of the question.

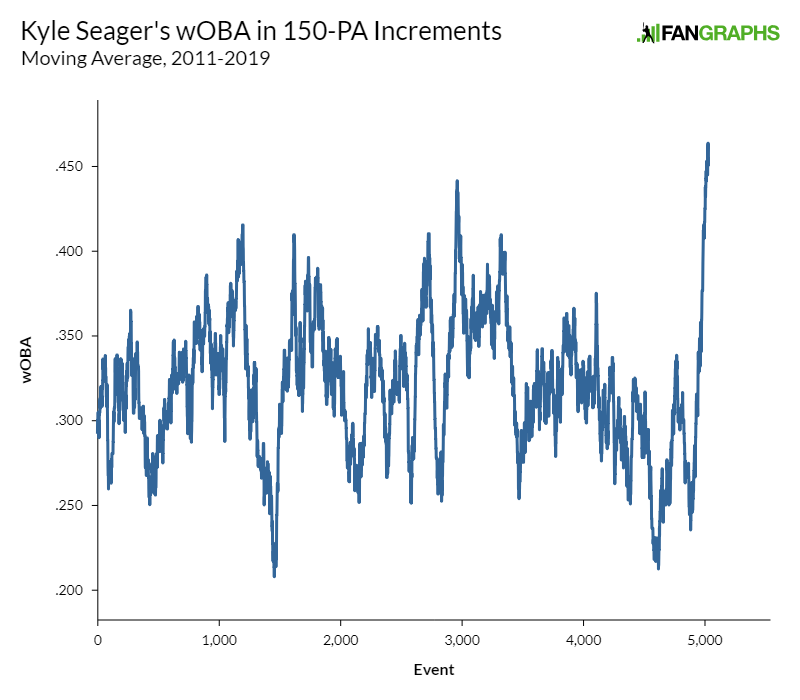

To check whether this is the case with Seager, I looked at a moving average of 150 plate appearance chunks throughout his career. We can talk through what that means, but first, look at the graph:

Yes, wOBA is scaled to on-base percentage and so is slightly higher this year than in the past, but this is new territory for Seager. This isn’t a case of him having a hot stretch in him every few months on average. He’s crushing the ball in a way he simply hasn’t before, not for this long.

Is this change swing-related? It seems somewhat unlikely, as Seager has always been a low-and-inside hitter with an uppercut swing, but let’s take a look. Here he is in 2018, hitting a center-cut fastball from Bartolo Colon a very long way:

And here he is mere days ago, hitting a similarly-located pitch from Taylor Guerrieri nearly as far:

Now, I’m no swing scientist, but I don’t see much difference in the key action points. The leg kick looks identical, the timing mechanism and load seem quite similar, and the bat path looks nearly identical. It’s not his classic stance, but he’s been tinkering with it for years now, and it doesn’t look to my eyes as though much has changed in 2019. Aside from a brief experiment with a crouch this year, his swing looks to be a constant.

If it’s not the swing, then what? As I mentioned, Seager is a fly ball hitter, and that’s continued this year. As with most fly ball hitters, he does more damage when he pulls balls in the air. For his career, he’s marginally better than average when it comes to getting to his pull side — he’s pulled 31.7% of his line drives, a smidge higher than the major league average of 29.7%. During his recent hot streak, he’s up to 38.4% (since July 25), albeit over only 73 batted balls. His pull rate is highest on inside pitches, and he’s done a good job of hunting those the last two months.

It works out to a difference of roughly five pulled balls, which is enough to be meaningful. For his career, he’s batted .582 with a 1.343 slugging percentage on balls he pulls in the air, as compared to .269/.420 when he goes to center or left field. That change alone is worth 12 points of batting average and 36 points of slugging over the 129 at-bats he’s logged in that time frame.

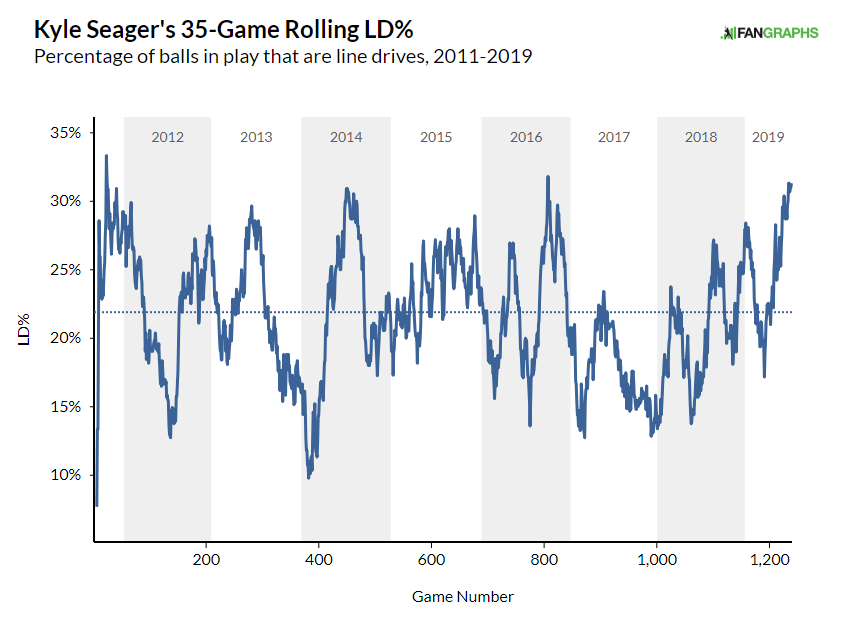

There’s more to it than that, of course. Seager has also gotten lucky in that time frame. He’s hitting 30.1% line drives, a number that figures to come down going forward:

Even accounting for those line drives, he’s done better on contact than you’d expect: his .489 wOBA on contact beats his .434 xwOBA on contact by a decent margin. When batted ball luck evens out and his line drive percentage comes back to earth, the overall package probably won’t continue to work out to a 160 wRC+.

Even if the recent streak has a bit of good fortune to it, how can you not be optimistic about this development? Seager is getting back to what he once was, a pull-and-fly-ball-happy slugger with good plate discipline. That plate discipline has held up in his recent run — he hasn’t gotten too swing-happy or liable to chase even as pitchers have challenged him less than in recent years during his hot streak.

In fact, this recent hot streak underscores something that you could easily lose in the Seager narrative. His first half performance this year? He was recovering from surgery on his hand, and nothing saps power like a hand injury. Viewed that way, should we really be surprised he wasn’t hitting for much power to start the year?

2018 was bad too — but again, an injury could be to blame. He fractured his toe in June of 2018 and though he didn’t spend any time on the IL, he had a gruesome 71 wRC+ after the injury. He claimed not to be affected by it, but try emulating Seager’s short leg kick and see how much pressure you’re putting on your left big toe. Now imagine that with a fracture. It’s not hard to see how that might slow him down.

Kyle Seager is 31 already. Even if he’s back to his former self, he can’t fight off age forever — before the season started, ZiPS projected him for 2.2 WAR in 2020 and 1.7 in 2021. Given the current state of the Mariners roster (and his contract, which has a $15 million team option in 2022), he might not ever make the playoffs as a key contributor in Seattle. He’s somewhat difficult for the team to trade as well, due to a clause in his contract that turns the 2022 team option into a player option if he’s dealt, which means he’s likely to stick around and slowly age instead of being sent off for a prospect infusion.

That’s all far-off and unknown, though. For now, Kyle Seager is back to what he was four years ago. He’s the best player on a struggling team, a reminder of what great baseball looks like even as the team that surrounds him scuffles. It’s not exactly making the playoffs, but in a frustrating year for Mariners fans, a resurgent Seager is a welcome reminder that missing the playoffs doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy baseball. Not bad for someone who looked cooked two months ago.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

“Corey’s brother” lol.

So glad Topps immortalized these.

Speaking of which, I expect Corey to bounce back soon in his own right and win an MVP.