Save Our Precious Endangered Triple

By and large, the new rule set for this season has led to more exciting baseball. Stolen bases are more common than they’ve been at any point this century. The average time of game is down more than half an hour from its peak in 2021, and lower than it’s been in almost 40 years. There’s less dead time between pitches and fewer annoying delays.

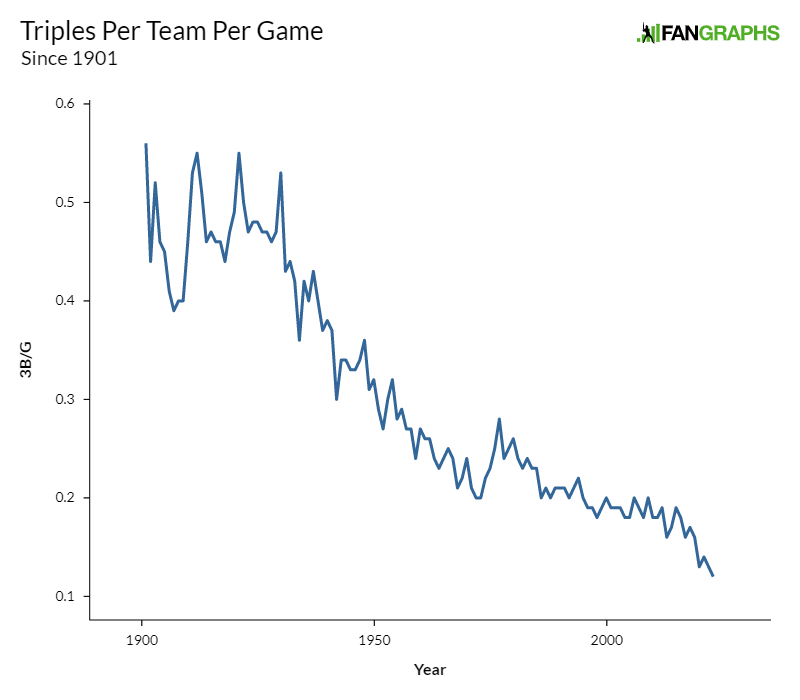

But as much as these rules represent a considered effort to goose the entertainment value of the sport, there wasn’t a mechanism to preserve baseball’s most exciting play: the triple. So concurrent with a rise in stolen bases, we’re down to 0.12 triples per team per game. According to the historical data on Baseball Reference, that’s an all-time low:

What a pity. Everyone loves a triple — the ultimate combination of speed, power, and audacity. Over the course of 11 to 15 seconds, the batter-runner makes multiple crucial decisions while the outfielders rummage around in search of the ball and their teammates scramble to their relay positions. No play in baseball forces so many people into action. (Except, for the pedantically inclined, the inside-the-park home run. And even that’s basically just a triple in which one of the outfielders falls on his face.)

The only thing not to like about a triple is that it involves so many moving parts, and such vast quantities of real estate, that it’s impossible to film. No matter when the director cuts from one camera angle to another, we’ll miss something: an overthrown cutoff man, an awkward carom, a runner doffing his helmet between second and third. (That last element is almost certainly why Corbin Carroll, a born triples hitter if ever one existed, maintains such a voluminous head of lettuce under his cap.)

Imagine that. Baseball, the most static, walking-pace sport you can get this side of golf, turns for a moment into a Carthaginian cavalry maneuver. And now we only see it happen about once every four games.

It was not always thus. Obviously, triples had their moment in the time before humanity realized that hitting the ball over the fence on purpose was a good thing. Wahoo Sam Crawford is known for two things: Being the Hall of Fame outfielder from the early 1900s Tigers who wasn’t Ty Cobb, and hitting more triples than any other player in major league history. In 1927, when Babe Ruth set a new record with 60 home runs, Earle Combs hit 23 triples. Lou Gehrig led the AL in doubles that season, meaning that three different Yankees led the league in the three different flavors of extra-base hit.

The Murderer’s Row Yankees are a fountain of trivia; the team as a whole hit .307. Wilcy Moore, a 30-year-old rookie, won 13 games out of the bullpen that season, which I figured had to be a record, but apparently in 1959 Elroy Face won 18 games in just 57 relief appearances that totaled 93 1/3 innings. Back in 1927, Moore also started 12 games and went the distance in six of them. Pitcher usage was absolutely wild before arm injuries were invented.

The triple thrived through the 1980s, when teams were built to challenge the axiom that one cannot steal first base. Lance Johnson led the AL in triples four years in a row from 1991 to 1994; he got traded to the Mets before the 1996 season, then led the National League with 21 triples. In 2007, Jimmy Rollins and Curtis Granderson crossed the 20-triple threshold in the same season.

For that matter, in 2015, Evan Gattis — who looks like John C. Reilly in a movie about early Great Depression-era boxing in which all the characters are CGI bears — hit 11 triples in a season. If Gattis can hit double digits, surely anyone can.

At least, you’d think so. Nobody’s hit double-digit triples in a season since before the pandemic. Nobody’s hit more than 10 since Ketel Marte in 2018. That 2015 season, in which Gattis and three other AL players hit 11 or more triples, is the only season since 2011 in which the AL leader in triples has had more than 10. The co-AL leaders in triples that year: Austin Jackson and Peter Bourjos.

Since the founding of the National League in 1876, there have only been two full seasons (i.e. 154 games or more) in which the NL leader had fewer than 10 triples: 2021 and 2022. This year, only four hitters have four triples so far, and only 22 have more than one. It’s not enough.

I have three theories as to why triples have become so scarce. The first is an extension of the prevailing conservatism (I’d say cowardice) regarding basestealing. Players and coaches are so scared of making outs on the bases — particularly when that out comes at third base — that they’re passing up makeable chances to advance. Look up the leaders in triples and you’ll find some extremely fast players (Shohei Ohtani, Trea Turner), and some generally savvy baserunners like J.T. Realmuto. You’ll also players like Cedric Mullins and Anthony Volpe, who run the bases like they’re being pursued by an indefatigable instrument of God’s vengeance. Salvation might not truly lie at the next unoccupied base, but we’ll never know for sure unless we keep running. Not that many guys run the bases that way anymore.

The next theory: Ballpark architecture. The list of the most triples-friendly parks in baseball comprises stadia that fall into one of two categories. The first has huge outfields, like Coors Field, Kauffman Stadium, and Comerica Park. The second has some novelty element in fair territory: The Wrigley Field ivy, Triples Alley in San Francisco, or any aspect of Fenway Park, which does not have a single square inch of normal outfield fence.

Going back to Gattis: He got to 11 triples because something about him, specifically, turned Lorenzo Cain — ordinarily one of the best defensive outfielders of his era — into Brad Hawpe. Cain booted one of Gattis’ triples across the Kauffman Stadium grass, and then granted Gattis another triple when he completely biffed it trying to summit Tal’s Hill. You want triples? Let the people who design mini golf courses design outfields. Hills in fair territory. Water features. Sam Miller’s pit. There is no obstacle too wacky.

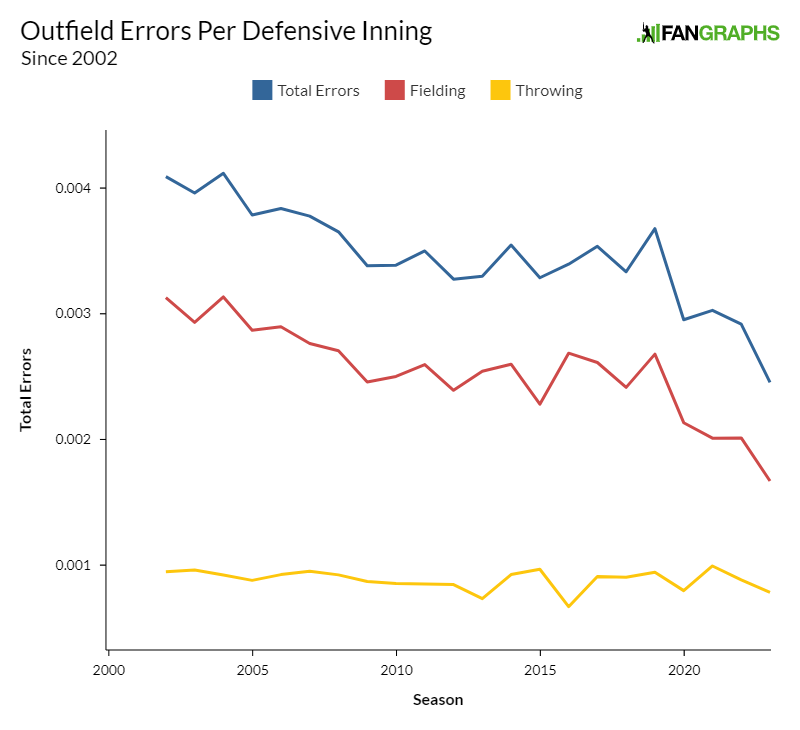

But the most important factor is probably the most boring and least correctible: Outfield defense is getting better. We don’t have fancy defensive stats very far back, and what we do have is frequently indexed to league average or replacement level, so it’s not that useful in terms of investigating league-wide trends. But the league-wide fielding percentage for outfielders in 1960 was .980. In 1997, it was .981. This year, it’s .990, the highest it’s ever been.

Now, obviously a triple depends on an outfielder not committing an error, but today’s outfielders just make routine plays routinely. Since 2002, when we have league-wide error data split out into throwing and fielding errors, you can see the precipitous drop in fielding error rate among outfielders:

So today’s would-be Crawfords and Grandersons are ripping the ball down the right field line and into the corner, or off the huge right field wall at PNC Park, and the guy who picks the ball up is Mookie Betts. Are you going to try to take liberties on Mookie Betts’ arm? Of course not, you’d have to be a lunatic to try to take liberties on Mookie Betts’ arm. Or Aaron Judge or Jackie Bradley Jr. or Ronald Acuña Jr., who’s had the top 10% of his outfield throws clock in at an average of 96.5 mph this year.

And it’s not like these trends are ever going to reverse themselves naturally. Ballplayers aren’t going to get slower and weaker, training and scouting methods aren’t going to get less meticulous. Every so often you might get a hitter who lucks into a surfeit of Looney Toons defensive errors and puts up a big number for triples. (Hello again, 2015 Evan Gattis.) But the days of a hitter having the triple be his calling card are probably behind us.

Unless MLB gets really into silly ballpark architecture. Come on, Rob. Deep down you know you want to see a windmill in right field. Make it happen.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

From 2015 to 2021 the average depth of a centerfielder has moved from 311 feet to 323 feet. Rightfielders went from 291 to 296.

We might expect to see this continue if the area of outfields is increased; there’s no reason to play close when a ball over your head is a double or triple, when one in front is a single.

I’d love to see outfield sizes increase for more action, including triples. I’m just not sure the nerds in front offices would play along with allowing more triples. The math ought to shake out to just play deeper, no?

The issue here is that the outfield dimensions of a lot of ball parks just are not easily adjustable. Yes, you could theoretically move in any fence line, but moving them back would require significant construction for some sites.

More breadth across the OF fence = more space for seats. Sell it as a profit center to the owners, and it will happen in 20 stadiums in a single offseason.