The 17-Year-Old Boy in the 16-Foot Boat

The summer of 1962 was one of political turmoil. Within the United States, the civil rights movement continued to fight for an end to racial segregation, and outside the United States, the globe-consuming tension of the Cold War continued to intensify. The Vietnam War continued to escalate, with Robert F. Kennedy declaring in February that the United States would not leave Vietnam until Communism was defeated. The Space Race proceeded apace, with both Americans and Russians being launched into orbit. And the brewing conflict between President Kennedy’s administration and the still-new Castro regime in Cuba was reaching a fever pitch. In February, President Kennedy extended the embargo on trade with Cuba to include almost all exports; in March, the participants in the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of the previous year were put on trial by the Cuban government, and in May were sentenced to 30 years of imprisonment. Both the United States and the USSR continued to test new kinds of nuclear warheads. The Cuban Missile Crisis loomed on the horizon; by midsummer, it was already clear that the pressure was about ready to boil over.

It was perhaps inevitable, then, that this conflict found its way into the relatively uneventful world of American professional baseball, where the most interesting thing going on was the Mets’ 120-loss inaugural season. Baseball in the United States, after all, is embedded in the national mythology, from the legends surrounding the sport’s invention to its status as America’s Pastime. The cultural significance of baseball was not lost to either side of the Cold War Conflict. New York Mirror columnist Dan Parker wrote that he was sure the world would be a better place “[i]f more ambassadors used sports instead of double talk as their medium of expression,” and that he’d “like to see the new envoy to Moscow introduce himself in the Kremlin by fetching Uncle Joe Stalin a resounding whack on the noggin with one of Joe Dimaggio’s castoff bats.”

Soviet paper of record Izvestia, meanwhile, in an attempt to undermine baseball’s status as a pillar of American values, claimed baseball was actually a descendant of the old Russian game lapta. In Cuba, where baseball had been the country’s most popular sport for almost a century, the game had developed yet another ideological purpose as a nationalist symbol, with the excellence of Cuban baseball demonstrating the values and victory of the revolution.

In August of 1962, the ideological tensions existing in baseball manifested themselves in the form of one unlikely person: a 17-year-old boy in a 16-foot boat.

***

On August 5th, 1962, the Associated Press ran a curious news item. The headline read “Cuban Baseball Player Branded as Traitor,” and opened with this paragraph:

A Cuban baseball player who signed a U.S. major league contract but kept it a secret so he could disqualify his nation’s entry in the Central American Games has been denounced as a traitor, Havana Radio said yesterday.

The story identified the player as one Manuel Enrique Ameroso Hernandez. There was no other information about him, no age or identifying characteristics. All that was known was what he had done, and what he had planned to do: He had signed a contract with a major league team, which made him a professional baseball player, and had intended to identify himself as such and claim political asylum in Jamaica, where the Central American Games were being held. The Cuban team, then, having had a professional play for their team, would be disqualified from the competition.

Given baseball’s cultural importance to Cuba and the revolution, this would have been a stunning act of sabotage if it had been successfully carried out. But Hernandez’s reserved, apathetic demeanor leading up to the competition drew suspicion, and he eventually admitted his plan to his teammates. His actions were condemned in the strongest possible terms. Teammates were quoted as saying that they “would prefer death a thousand times before selling ourselves for the bloody dollars of the Yankee monopolies,” and the team issued a statement condemning “the traitorous and miserable attitude of Ameroso Hernandez for having signed as a professional and keeping this secret for the ruinous and cowardly object [of giving] our enemies the opportunity to disqualify our invincible team.” There was no clarification of what was to happen to Hernandez, nor of which major league team he had signed with in the first place.

In the coming days, as the story spread in the American media, more information came out about Hernandez. There was, first, the fact of his talent: Raul Castro had only recently sung Hernandez’s praises on the national stage as Cuban baseball’s finest player, and assessed his annual value at $60,000. (The highest salary in the major leagues in 1962 was $90,000, earned by both Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays.) This revelation was followed by one that made the former all the more surprising: Hernandez was only 17 years old.

American newspapers jumped on the opportunity to display the evils of the Castro regime, and testimony was sought from Cubans already involved in American baseball. Scout Tony Pacheco said that he had seen the young man pitch two years prior, and that Minnie Miñoso of the Cardinals — a former star of the Negro Leagues, and the first Black Cuban to play in the majors — knew of Hernandez as well. Pacheco had heard that Hernandez once tried to flee Cuba by boat before gunfire prompted him to retreat, and speculated that Fidel Castro was making an example of him to discourage similar plots from the country’s young baseball talents. American commentators strongly implied that Hernandez was either already dead or shortly to be killed. Columnist Tommy Fitzgerald of the Miami News wrote on August 6th that Hernandez’s four-part name “may be longer than the remaining number of his days.”

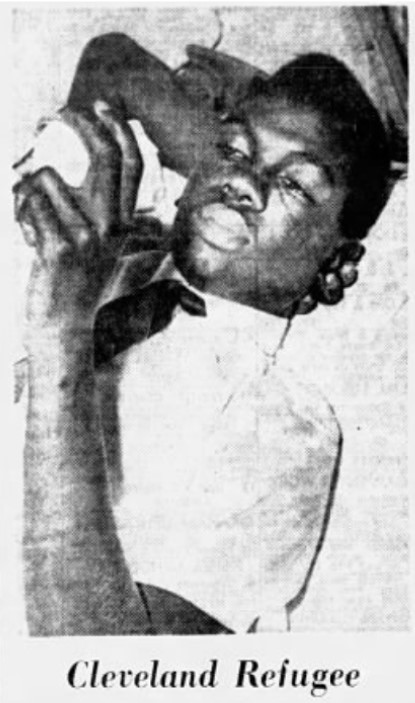

It didn’t take long for Fitzgerald’s estimation of Hernandez’s life expectancy to prove incorrect. Six days after he wrote his column, on August 12, another AP news item went out: Hernandez had made landfall on a beach in Marathon, Florida, having traveled there over 17 hours on a 16-foot skiff with four other people. From there, he made his way to the immigration office in Miami, where he kept an appointment he had made with Indians scout Julio de Arcos. De Arcos had been the one who offered Hernandez an opportunity to play in the Indians’ system; now that he was in the United States, de Arcos told the media that he would call Cleveland to arrange a tryout.

As more information emerged about Hernandez, it became clear that the American and/or Cuban media had misrepresented some aspects of the story — even something as basic as his name, which was not “Manuel Enrique Ameroso Hernandez,” but, in fact, Manuel Enrique Hernandez Gazmuri. (“Amoroso” was a nickname.) Uncontested were the facts that Gazmuri was a left-handed pitcher with a 10-2 record that season in Cuban amateur baseball, that those 10 wins included seven shutouts and three no-hitters, that the two losses were both by a score of 1-0. But reports couldn’t seem to agree whether he was 16 or 17 years old, nor whether his boat journey lasted 16 or 17 hours. De Arcos flew Gazmuri to Cleveland, where he signed a contract with the Indians on August 14 — thus calling into question the entire premise of Gazmuri’s aborted sabotage of the national team, the tale with which this saga began.

On August 21, yet another divergent account of Gazmuri’s defection appeared in the Tampa Times. In this telling, the Cuban government had gifted Gazmuri the house they had seized from fellow pitcher-defector Sandy Consuegra — a gift that Gazmuri refused, thus arousing suspicion that he intended to defect. No mention is made of an intended sabotage at the Central American and Caribbean Games, though the article does fill in some details of Gazmuri’s boat journey: that they had left Cuba with only a jug of water, a can of meat, and some chocolate, and that their boat had stalled three times. The article also included this dubious tidbit: “His friends call him “Hello” because that is the only bit of English he knows.”

***

Gazmuri made his debut — on the mound and at the plate — with the Charleston, West Virginia Indians, in the Class A Eastern League, on August 22. One can only imagine what was going through his mind. He was a 17-year-old kid who, within the space of two weeks, found himself playing professional baseball in a foreign country, where everyone spoke a foreign language, thousands of miles from a home he could never return to. A running theme in all the reporting on Gazmuri was that he was never asked for his take on his own life, likely because there was no one writing who could either speak Spanish or cared to translate.

Still, on his first night on the field in the United States, in front of a crowd of 562 people in Binghamton, New York, Gazmuri’s skills spoke for themselves. On the mound, he allowed just one unearned run in three innings; at the plate, he hit a two-run homer in his very first professional at-bat. His performance prompted this response from Binghamton Press and Sun-Bulletin sports columnist Dave Rossie:

At the risk of alienating the super-patriots of the House Un-American Activities Committee, this witness hereby seconds the motion by Senor Raul Castro, an avowed Communist. That Gazmuri kid is muy magnifico.

The Miami News, reporting on the event, quoted manager Johnny Lipon as being a little less enthusiastic — “He didn’t look bad, did he?” the former major leaguer said, before noting that Gazmuri’s control “wasn’t as good as it should be.”

What could be agreed upon, though, was that Gazmuri was a heartwarming representative of the value of American freedom. “Only in America…” the Miami News report opened. In the Huntsville Mirror on September 8th, the “most heartwarming touching story” of Gazmuri’s escape was introduced with this line: “Men everywhere are holding their hands high, crying for freedom.”

***

Gazmuri signed another contract with the Indians on February 5 of the following year. The reporting around his signing dubbed him the “spunkiest” pitcher ever to come out of Cuba. This was the last time Gazmuri was the subject of any significant media attention. He played three seasons with the Dubuque Packers, each one worse than the last. His batting line went from .238/.343/.420, to .269/.338/.413, to .205/.278/.303; he pitched seven games with an 8.05 ERA in 1963, after which he lost his job as a regular pitcher, transitioning to a first-base role and pitching only when needed. There is no record of him playing professional baseball after 1965. There is, in fact, no record of him anywhere that I can find after that year.

In 1966, Gazmuri would have been just 20 years old.

***

Manuel Gazmuri was one of the first Cuban baseball players whose flight from his home country under precarious circumstances caught the attention of the American public. He was far from the last. These stories are familiar to us now: José Fernández pulling his mother out of the water, Yasiel Puig’s 50-mile trek through the swamp, Jose Abreu swallowing a fake passport. These stories are part of why MLB attempted to implement a posting system for Cuban players over this offseason by making a deal with the Cuban Federation. The recent scuttling of that deal ensures that, until one or both of the countries involved makes a significant change to their foreign policy, these stories will continue to be created.

The story of Manuel Gazmuri, like those of all Cuban players who have made their way to the major leagues, is remarkable. It is a striking display of willpower and determination, of the strength that people can summon under extraordinary circumstances. But it is also a story from which Gazmuri’s own perspective is shockingly absent. It is a story whose meaning changed depending on who was doing the telling. In Cuba, Gazmuri was a model of revolutionary youth and excellence, until he was a vicious traitor. In the United States, Gazmuri was a symbol of Castro’s tyranny, a heartwarming symbol of the value of American freedoms. And then, to both, he was nothing. He faded away, never having the opportunity to take control over his own narrative. He was at all points a signifier of some broader ideological meaning. He never got to signify himself — his determination, his experience, his incredible baseball talent.

I don’t know what happened to Gazmuri after his baseball career ended — what he did, who he connected with, even whether or not he’s still alive today. I wish I did know. I wish that we could hear the story of the 17-year-old in the 16-foot boat, the best baseball player in all of Cuba, from the only person who lived its truth. But it’s too late now. Nobody ever asked him to tell it.

RJ is the dilettante-in-residence at FanGraphs. Previous work can be found at Baseball Prospectus, VICE Sports, and The Hardball Times.

Rachel, a search on Ancestry.com shows this from U.S. Social Security records:

Name

Manuel Enrique Gazmuri

Birth

dd mm year city, Cuba

Death

mm 1991

Hi died at only 45 years of age?

Unfortunately, it seems a lot less likely now that we’ll ever here his side of the story.