The Best Bullpens in Baseball

After finishing up some research noting the wide gap between the quality of relief innings depending on the importance of the situation this season, it felt necessary to take a similar look at team performance. If teams were deploying less-good relievers in low leverage situations and good ones in high leverage situations, it could distort our sense of the quality of a bullpen when looking at overall numbers.

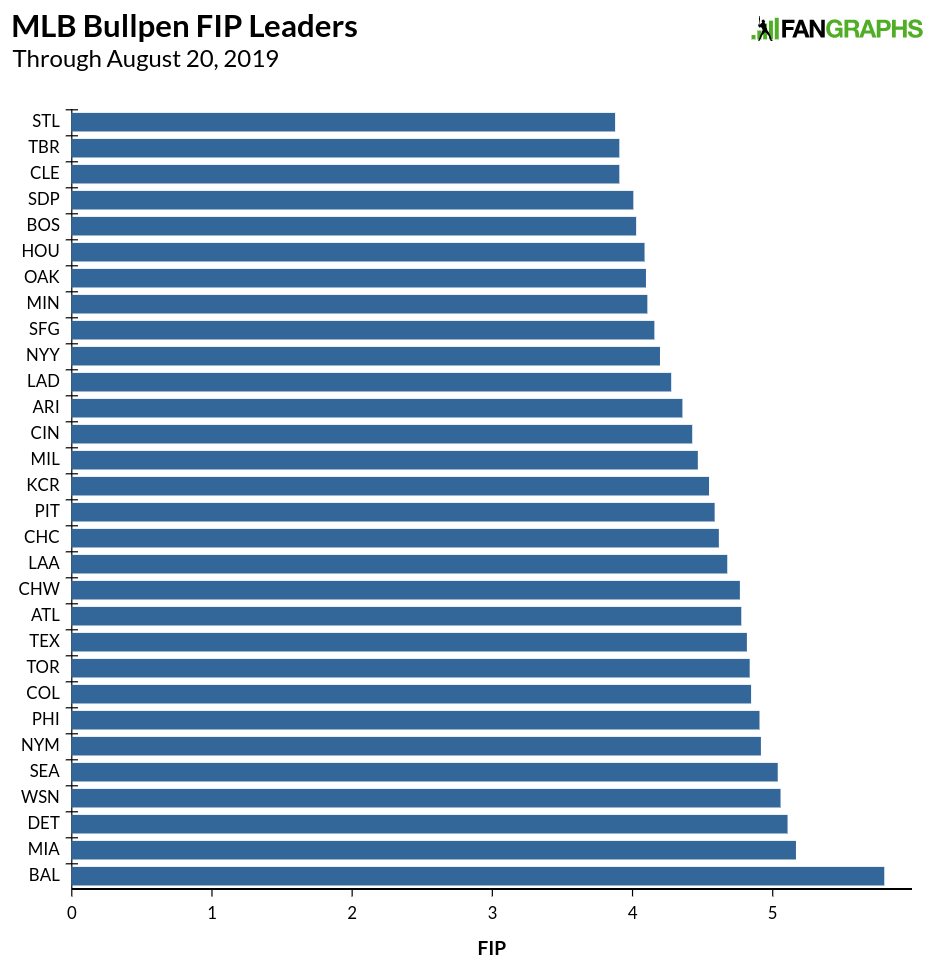

We’ll start with a pretty generic view of bullpens this year, with FIP by team:

The Cardinals have the lowest FIP of any bullpen this season, as the group as a whole has pitched very well. The Rays coming in second and first in the American League is somewhat of a surprise given their use of an opener in half their games; they are losing about 60 good relief innings and replacing them with around 180 good-but-not-as-good starting pitching-type innings. The teams fall down in a nice cascade the rest of the way, with the Baltimore Orioles providing a a very heavy base at the bottom of baseball.

But not all innings are created equal, and some of the innings pitched by bullpens are more important than others. If we separate meaningful innings (medium leverage and high leverage) from less important innings (low leverage), we can get a sense of how good a team’s bullpen is when it matters. This also could provide a better sense of which teams might be better prepared for the playoffs, given the consolidation of relief innings in October:

If you wanted to know how the Giants can have a run differential of negative 54 and be a 56-70 team by BaseRuns but still end up at .500, this graph explains it. When the Giants have had important relief innings, they have performed incredibly well. The Red Sox bullpen maybe hasn’t been quite as bad as it has seemed, while the two overall leaders in St. Louis and Tampa Bay have moved closer to the middle of the pack. If you want to know why Pittsburgh has collapsed, their bullpen performance is a huge part of the reason.

Here are the respective performances in low leverage situations:

St. Louis’ depth in the pen has put it at the top of baseball, while the Dodgers’ depth has masked the struggles the team has had in close games a bit. It’s the performance in these situations that makes Baltimore’s pen the worst in the game. As to how the performance in important situations relates to those in less important plate appearances, the answer is not much. Here’s a scatter plot of each team’s FIP:

The two figures aren’t correlated. Some of that is random, and some of it is that different pitchers are assigned to different types of situations; the pitchers put in close games are generally going to be better. Within teams, the number of innings in each situation can vary quite a bit. The graph below shows the percentage of a team’s bullpen innings that happen in low leverage situations:

The Rays are at the very bottom, likely due to their use of an openers, while the other teams at the bottom have had their bullpen pitch in more meaningful situations as a percentage of their overall bullpen use. The very top of the list includes some very bad teams with very bad bullpens. In terms of just innings, the leaderboard looks like this:

We still see mostly bad teams in the lead, with mostly good teams throwing fewer low leverage innings. The Angels and Rays have used an opener a decent amount of the time, which is going to explain how they are ranked highly in sheer number of innings but weren’t near the top when it came to the percentage of low leverage innings.

Would you be interested in a stat the helps capture some of the discrepancies above? A stat that factored in whether a team was pitching in important situations to give a greater sense for just how a strong or weak a bullpen might be? This isn’t a trick, though if the answer is yes, there’s a fairly simple answer. WAR factors in leverage for relievers, so the pitchers pitching in important situations get a little more credit than ones pitching in unimportant situations. We have to assume that pitchers are mainly used according to their talents, but general pitcher performance in low leverage situations compared to medium and high leverage situations seems to indicate this is the case.

WAR also controls for park and league, but if you don’t quite know what to make of the stats above on a team-by-team basis or how to weight different types of appearances, let WAR be your guide. Here are the current WAR leaders for bullpens by team:

The Yankees, due to their prowess in important situations, rate higher than other clubs with better FIPs. The Cardinals take a small hit, and teams like the Pirates move down a bit as well due to difficulty getting important outs (in addition to park and league factors). The NL East looks like it is putting together the worse divisional bullpen in baseball, with all five teams in the bottom seven. There are pretty definitive tiers, with the good teams around four wins or more, the middle class of teams around two wins starting with the Giants and moving down to the Pirates, and the poor bullpens starting with the Blue Jay down to the Marlins. The only contenders in the bottom group are the four NL east clubs vying for a playoff spot and the Chicago Cubs, who are hoping Craig Kimbrel can right the ship.

Craig Edwards can be found on twitter @craigjedwards.

Leverage is not equivalent to “importance.” Certainly some parts of how we define leverage are equivalent to importance, since pitching a scoreless inning is less valuable if you’re down by 15 than if you’re down by one, and an out is more valuable with the bases loaded and two out than at other times. But it’s remarkable how often an “unimportant” inning suddenly becomes “important” because someone just scored seven runs on you.

Part of the reason why the Rays have been successful is that they’re not wedded to the ridiculous idea that earlier innings are less important than later ones. Runs count the same amount regardless of the inning that they’re scored, so it behooves a team to try and prevent them earlier as well as later.

An unimportant scenario cannot suddenly important scenario in baseball, using your example, it would take at least 4 plate appearances to concede 7 runs. Giving the pitching team time to react to the changes in leverage and win probability.

This season teams have scored 5 or more runs in 1.2% of innings so yes an innings can get away from a team but isn’t that often.

The bigger point is that it’s generally the runs that are scored that is important, not the inning. There’s a flaw in the way leverage is usually operationalized that if you give up a home run in the first pitch of the game that is somehow less “important” than if someone someone gives up a home run (in the same base, out, run state) in the 9th inning. You still lost the game 1-0 in the exact same way. The important innings are the ones where the runs are scored.

Leverage is an attempt to quantify a feeling of excitement as it is happening, but understanding what is “important” in a game can only be determined retrospectively. Leverage is therefore a less than ideal tool for this task.

This isn’t true though. It is much better to give up a run in a 0-0 game in the first then a 0-0 game in the 9th. It is only equivalent if you assume that your team won’t score the rest of the game. So, ex-post the impact is the same, but ex-ante it is not.

Put another way imagine a game where it is 0-0 in the bottom of the 9th. The manager can either give up a run now or in the first inning tomorrow. That is an easy choice. If you give up a run now your expected wins over the two games is 0.5 (assuming even teams, lost today and 0.5 from tomorrow). If you give it up tomorrow your expected wins is probably something like 0.9 (0.5 today, 0.4 tomorrow since you are down 1-0, can quibble with the 0.4 I suppose).

Right, but ex-post is the actual level of importance. It explains whether or not you did win the game and how you did it, not how you might win the game and the possible routes towards it. If you are going to give up a home run and lose 1-0, whenever that home run happens is the most important moment. If you’re trying to explain who was best when it was most important, you need to calculate it out based on what actually happened.

I can see both sides of the argument but one thing I’d like to see is the leverage bonus eliminated or reduced in importance in WAR calculations. There are two issues that I see:

1) Only relievers receive a leverage bonus. This is true for both Fangraphs and Baseball Reference. So if a starter goes the distance and his teams wins by one run (for example), he gets no leverage bonus. But any reliever brought into that same game is automatically given a leverage bonus. I really don’t see how that makes any sense.

2) While there is a difference in quality among relievers, there’s also a lot of fungibility among them. The fact that a manager uses one reliever as his closer and uses other relievers earlier in the game is often a matter of personal preference and not actual talent level or ability to pitch in a certain situation.

I think the idea behind the leverage for relievers is that because you can put them in during a particular point in the game, you can do it when there’s more on the line, thus making them more valuable.

But that makes it only a bit more coherent, because we don’t do the same for pinch-hitters. We (rightly) understand that just because a guy is pinch-hitting for a pitcher in the 8th inning instead of the 7th inning doesn’t actually matter enough to calculate it out.

But more valuable relative to what? We’re trying to calculate Wins Above Replacement and with relievers, the replacement is often a guy who’s just as good. Or in some cases may even be better. Looking at the Indians, there are about 4-5 relievers who are indistinguishable from one another. I really have no idea who Francona should use when and I doubt he does either.

If I, a genie, put a pitcher on your roster that is guaranteed to strike out every batter on three pitches but can only throw 81 pitches per season, how valuable do you think that pitcher would be?

You could use him to throw an Immaculate Game, practically guaranteeing a W, about 0.7 wins more than you’d get if you had to use replacement level pitchers instead.

You wouldn’t do that, though, if your goal were to maximize wins. You’d deploy your magic pitcher in the highest leverage situations and win at least 5 games you would’ve lost had you been forced to use a replacement level pitcher instead.

You’re correct that the same logic applies to pinch hitters but in practice PHs aren’t usually better than most of the lineup so their deployment tends to be based on the batting order making their leverage at least partially (if not mostly) coincidental to their deployment. Isolating the amount of leverage that “belongs” to the PH would be a chore and my gut is that it wouldn’t make much difference in the total WAR, but it does make sense to give a PH credit for some amount of leverage.

So several points:

1) The magical genie pitcher invented by Sciential doesn’t exist. Nor does anything close to it exist. The argument might have validity if pitchers like that existed. But they don’t.

2) Teams have consistently won 95% of games that they led going into the 9th inning. They did it back when starters tended to pitch complete games, they did it when managers used a variety of relievers to finish games, they did it when “closers” pitched 2+ innings at a time, and they’ve done it in the modern era of 1 inning closers. So if different strategies all lead to the same outcome, where exactly is the added value of pitching high leverage innings?

3) Back to starters. Let’s say two starters have the same WAR but one of them averages 5 innings a game and the other averages 6. We’ll often say that there equivalent since they have the same WAR. Or that the pitcher who averages 5 innings a game is better because his WAR/IP is higher. But is that true? Doesn’t the 6 innings/game pitcher deserve some extra credit for reducing bullpen usage? Plus, we know that pitchers tend to pitch worse the longer they pitcher. So the 6 inning pitcher is likely getting penalized in his stats because he goes deeper into games. And yet we just ignore that instead of giving him some sort of credit for pitching higher leverage innings.

4) SadTrombone talked about pinch hitters. But I think we can also extend that argument to position players in general. If two position players are exactly the same in every aspect except one of them does all of his damage in the first 5 innings and the other does all of his damage from the 6th inning on, they still end up with the exact same WAR. In fact, if memory serves me correctly, this was the pot that Bill James tried to stir a few years ago relative to Aaron Judge. James’ argument was rejected by the powers that be. But those same powers that be don’t reject that argument when it comes to relievers. In my opinion, they’re trying to have things both ways…the context in which performance occurs either matters when determining value or it doesn’t.

BTW, I’m going to make two final points and then shut up:

1) The leverage bonus is applied without regard to who is being faced. So a reliever n the 8th inning facing the 3-5 betters get a lower bonus than a closer in the ninth inning facing the 6-8 batters.

2) The leverage bonus is applied regardless of how the reliever actually pitches. The argument is being advanced that they’re pitching more valuable innings and therefore doing more to help their teams win. But, for example. if a closer has a complete meltdown in the 9th inning and directly “causes” their team to lose, they STILL get the leverage bonus.

ex-post does give you the final word on which AB was important and if you lose by 3-2 on a walkoff solo shot, sure, the first inning HR was just as important as the last AB that cost you the game, but it’s absolutely not true that a manager can know that his anemic offense will only put up 2 runs, so his decision making cannot in any way use the kind of ex-post analysis that fans and writers use.

I was going to respond but BaseballBreaksYourHeart did it quicker and better than I could, so thank you!

I do get that a run is a run whenever it is scored and that you don’t know the true importance of said run until the game has ended. But you are surmising a game of baseball down to a single play by saying the play were the run was scored was the only important one and every other play has zero importance.

I believe the stats purpose is to help quantify key moments in a game and see how team react or manage those scenarios. Personally I believe that an at bats importance is the same regardless of the outcome.

Your version of importance places no value in scenarios where no run is scored, which think is inherently incorrect. For example in a bottom of the 9th, bases loaded, 2 outs, down by one scenario, you importance changes based on the result of that at bat. If the run is scored the at was very important but if it didn’t it wasn’t.

No, I strongly believe that base-out state is very important. Although it’s not a repeatable skill or anything, the way baseball is divided into innings means that both the overall score and the progress you’ve made within the inning is important. It’s just that you have much better information about importance once the game is over and you know the number of runs a team needed to score/not give up, instead of guessing based on inning # and an incomplete scoreboard.

Storytelling afterwards is its own thing, but managers have to manage prospectively, not retrospectively. You make the decision based on present state given the possible futures.

The first pitch of the game comes on a LI of 1, telling the manager “use a pretty good pitcher. ” Tied in the 9th is higher LI, telling the manager “use the best relievers you’ve got.” What do you not like about what LI is saying there?

LI and its relatives (like WPA) can be used to explain what it’s like watching a game, or how to bet, or things like that.

That’s not how a lot of writers use LI (at least not most of the time, and also not here). If you want to assess value or importance or anything, you should take all the information you can get. Instead, LI and WPA and its ilk deliberately ignore what actually happened in favor of what people were saying at the time.

Here’s an analogy, if an extreme one. Imagine that Mike Trout suffers a terrible injury and is never the same again, putting up 0.0 fWAR over the remainder of his contract (I’m crying just thinking about it). Was the extension the Angels gave him a good decision? Yes. We can only judge it based on the information they had at the time. Does that mean that Mike Trout has remained a valuable player? No. That’s the difference between appropriately judging decisions based on the knowledge the actors had, and re-writing history because we’ve confused a simulation with reality.

As I understand it, LI for a given situation is ultimately based on what has happened in the past when similar situations occurred. Pooh-poohing LI in favor of the thing that actually happened would therefore be comparable to throwing out a large data set in favor of a one-event sample.

Also, there is no such thing as a predetermined outcome, so you can’t say that something was more or less important than it seemed at the time. If that 1-0 game didn’t have that home run in the first inning, it could have turned into a 4-2, 9-inning win for either side. You would have to know what would have happened if the home run WASN’T hit.

I’m baffled that so many people are so in favor of using leverage index to determine value. It’s like the difference between using projections to determine value and WAR. You wouldn’t use the projection to determine the MVP, and while using WAR might help you figure out who’s going to be good next year, mostly that’s what the projections are there for.

No it isn’t. Leverage doesn’t change what happened, and what happens doesn’t change leverage. Context matters.

But leverage literally doesn’t change based on what actually happens. It only changes based on what you knew at the time.

While I do think additional leverage should be given based on the inning because it determines how many more opportunities (outs) teams have to affect the score, maybe it’s too much in relation to the other parts of the equation (score, number of outs and base runners – which should be inning independent).

This reminds me of the catcher framing debate. It seems logical, given how everything else is scored/credited, that the only time a catcher should get credit for framing is on a called third strike where the pitch was outside the strike zone (an actual outcome to the PA), and even the amount of credit for that can be debated.

I see a similar issue with how yesterday’s post by Craig seemed to equate “low leverage” with “blowout” as well as the chart title in this post equating “low leverage” with “unimportant innings”. (To be fair, there are other places in this post where Craig uses “less important” innings to equate to “low leverage”.)

Looking through recent some game logs and using Fangraphs’ definition of low leverage (LI <0.85), there are half-innings in what we think of close games – such as a team batting up by 1 run really late in a game – that start as "low leverage innings" by this definition. As I understand the math of it, that's because the the trailing team will have a fairly low (sub-25%) win expectancy even if the team in the lead doesn't score any additional runs, so there's only so much the win expectancy can move while the leading team bats.

The math supports the conventional wisdom of not using a team's top few relievers in that situation, but I'm not inclined to write them off as "unimportant" because of sadtrombone's point that's not fully knowable until after the game. Said with a bit more math, a team that's very often allowing add-on runs that stretch 1 run deficits to 2+ run deficits in the 8th (or 2-run deficits to larger deficits a bit earlier in the game) is constantly lowering its win expectancy from not very good (maybe 20% to 25%) to really unlikely (<10%), and that probably adds up over the course of a season.

If we want to focus on "blowouts" or "unimportant innings", we need a definition that's more restricted than the Fangraphs definition of low leverage. Craig mentioned 6-1 games in the 4th inning in yesterday's post. That's a half-inning that starts with LI of 0.16 for the team in the lead (if it's the home team), which is so low that I don't see it as a fair representation for the low leverage bucket.