The (Lack of A) Conspiracy Against Pitcher Wins

Yesterday, a reader in my chat asked me a question I had no idea how to answer: Are teams increasingly pulling pitchers from games after 4 2/3 innings, even with the lead, in an attempt to cut down on wins and arbitration payouts? Here’s the question in its entirety:

My snap judgment was “probably not.” After thinking about it for a while longer, my answer is still no – but now I have some neat graphs and charts that will hopefully make the point clear. Without further ado, let’s dive into the shape of league-wide starting pitching trends since 1974, the first year in our database of game logs.

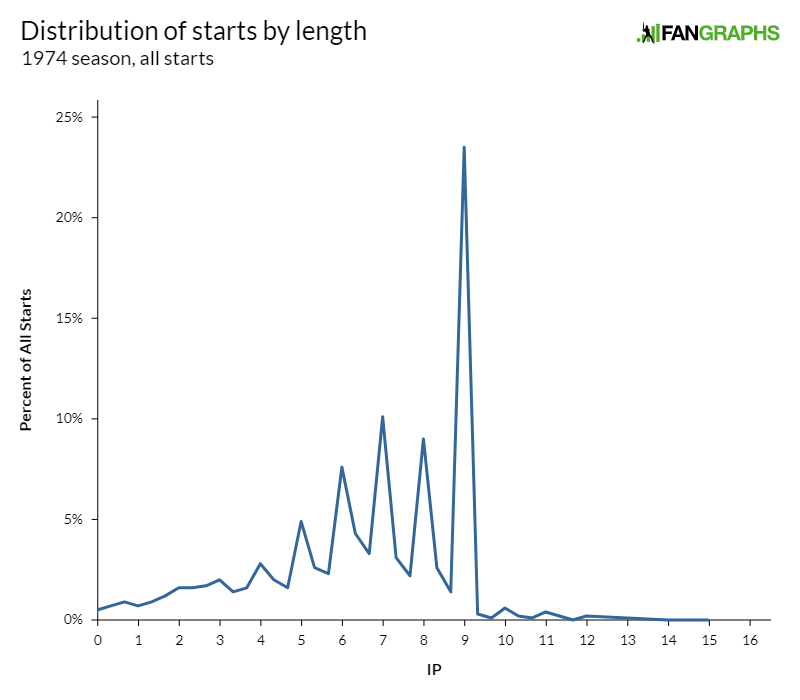

In 1974, the concept of a five-inning start existed, but it was almost an insult. More than a quarter of starts went nine or more innings. That’s hard to do, particularly when that’s an impossible feat for a visiting team that trails after the top of the ninth inning. If that’s roughly a quarter of games (it’s not every game the visiting team loses, but road teams lose more than half of the games they play), that means that roughly a third of eligible starts went at least a full nine. That’s downright wild. Here’s a graph of that wildness:

There were a few short starts, even back in the 1970s – 21% of starts went fewer than five innings. More importantly, a pattern we’ll see repeated again and again is immediately evident. Managers like leaving their pitchers in for a whole number of innings. It’s a natural endpoint to the day, mid-inning pitching changes can be tricky, it’s a way of boosting your starter’s confidence – there are plenty of reasons for this to be the case, and I’m not sure which is most true, but that’s just a fact of baseball. Managers like to pull their starters between innings rather than partway through.

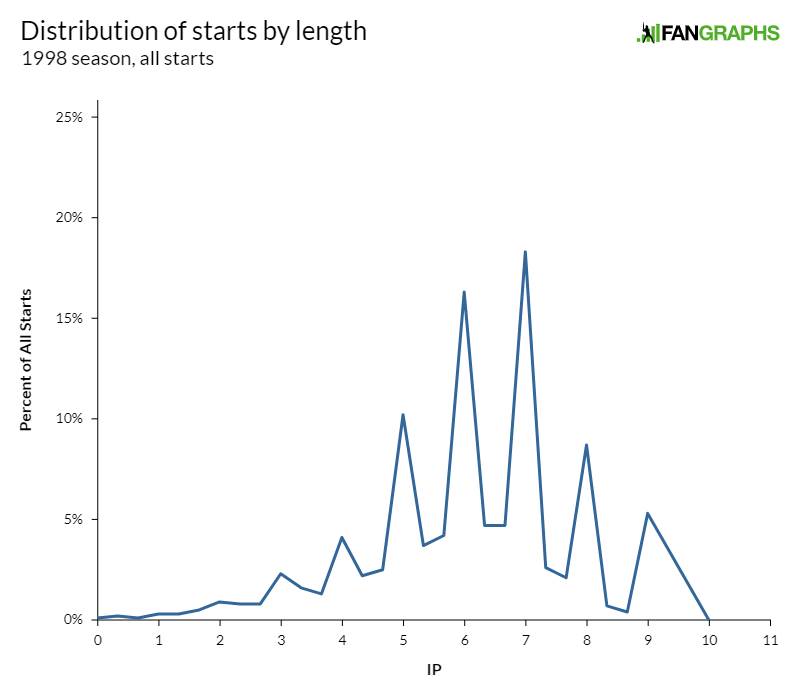

Next, let’s fast-forward to 1998, the home run chase at the peak of the PED era, or whatever you want to call that era of the baseball. Starters weren’t going nearly as deep as they used to, with relief pitchers taking up an increasing share of innings. Complete games were no longer the norm, but seven-inning starts were:

Interestingly, there were now fewer starts that lasted under five innings. I always heard growing up that the managers of yesteryear were more willing to pull their starter if they “just didn’t have it” that day. It makes sense on its face – reliever workload management was far less important given how deep starters went into games, so a starter wearing one for the team didn’t make sense. Getting someone in there who gave the team a chance to win was more important than who would pick up innings tomorrow.

In the late 1990s, that was no longer the case, but most of the rest of the patterns of pitching usage from the 1970s were still there. Whole innings were still preferable. Starters threw a ton of innings. There was nothing special about five innings, at least nothing evident in the data. It was merely a whole inning like any other. Two-thirds of starts that ended in the fifth inning went the full five, but the same was true for the sixth, seventh, eighth, and ninth innings. In every inning past the fourth, a filibuster-proof majority of starts went the full three outs in that inning.

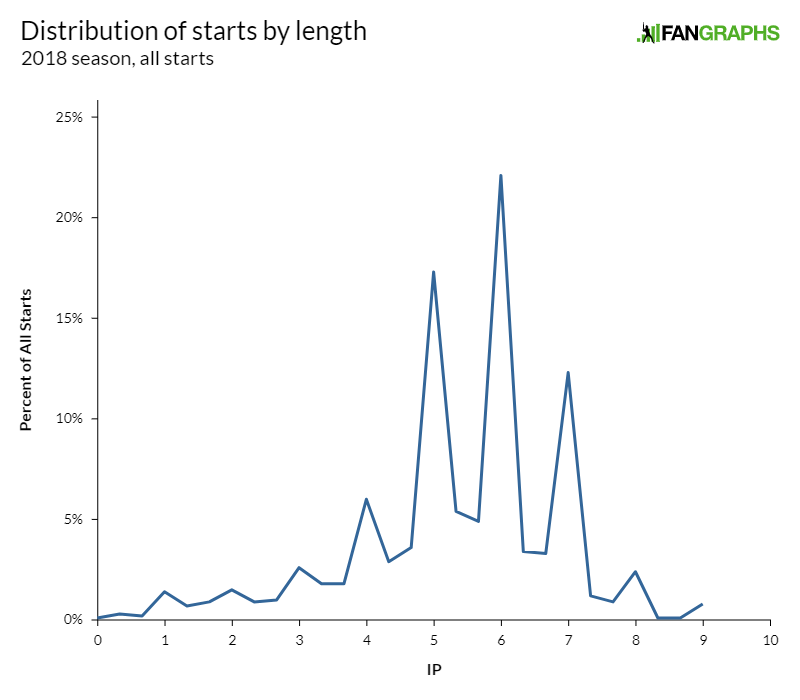

One more fast-forward, and I promise I’ll get to my case. Next, let’s go to 2018, the first year the Rays revived the opener, leading to far more short starts:

The march towards lighter workloads was in full swing. Roughly a quarter of starts lasted longer than six innings, down from 48% in 1998. More than a quarter of starts lasted fewer than five full innings, now easily surpassing 1974 and ’98. The mode start lasted six innings. We’ve all felt these changes implicitly when we watch baseball, so you probably don’t need to see the numbers, but a sea change had already happened.

Meanwhile, managers started leaning into getting their starters five innings. Starters who entered the fifth inning and were pulled before the sixth inning threw the full fifth three-quarters of the time. That’s the highest such share for any inning, and higher than it had been in 1974 or ’98. In other words, managers were working to maximize pitchers’ eligibility for a win. Five innings is a magic number, and a quick look at the data shows that managers knew it.

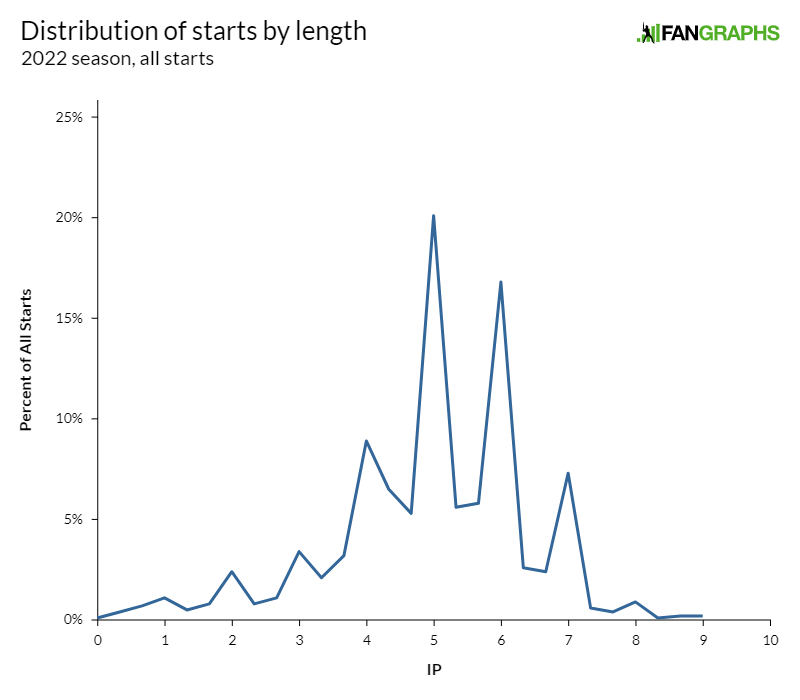

Finally, let’s get to 2022. Those past years were all a preamble to this:

Goodness gracious, are five-inning starts popular these days. Relievers are rapidly replacing innings starters used to throw. Twenty percent of starts have gone exactly five innings this year, the largest share of five-inning starts in history. The average start length is way down, of course: 37% of starts have gone fewer than five innings. It’s all down, every imaginable category. Just 2.3% of starts have gone longer than seven innings. Only 42.8% of starts have lasted more than five innings, the second-lowest mark in history, trailing only the weirdo 2020 season.

Despite that, managers are still giving their starters a chance at a win – at least, on a relative basis. The starter may not be long for the game when he takes the mound for the fifth inning, but he still stands a very good chance of completing that inning. It’s not the 75% share from 2018, but it’s still 63%, higher than every inning other than the first few, where most of the starts are planned whole-inning stints by openers. Managers are increasingly willing to make mid-inning pitching changes – but they still show some deference in the fifth.

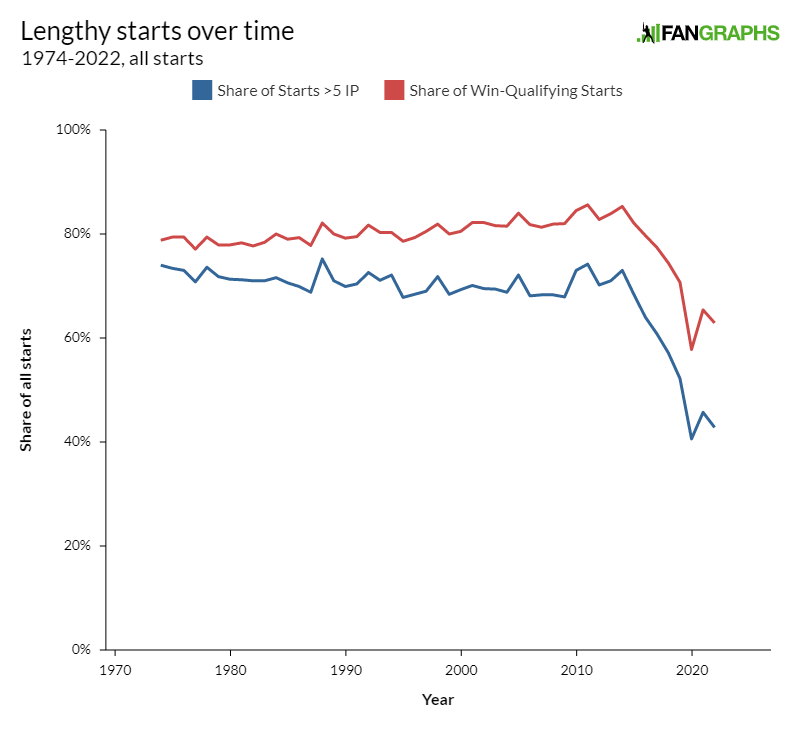

In other words, managers don’t appear to be tilting the scales one way or the other. They’re still erring in favor of letting their starters complete any inning they start, just like they always have. The fifth is the inning where they’re most willing to do it, a trend that picked up as starter workloads declined. The result is an interesting wedge between long starts and win-qualifying starts:

I don’t have any special knowledge to impart here. For the most part, it seems like managers are behaving like you’d expect a lot of former players who nonetheless answer to the front office to behave. Are they trying to get their starters five innings? It seems like it. But they’re also exercising ever-tighter leashes.

Of course, this isn’t exactly the question I was setting out to answer. What about starts that go exactly 4 2/3 innings, with the starter still having the lead when pulled? If that specific thing is what you’re interested in, well, you’re not exactly in luck, because it almost never happens. I culled our database for every time a starter left the game after 4 2/3 innings while holding the lead. Here’s the percentage of starts in a given year that have ended with two outs in the fifth inning, with the pitcher being replaced an out away from qualifying for a win:

Hey, wow, there’s something here! It’s not exactly new this year, but nearly 1% of starts are now ending with the starter angrily walking off the mound, a win just outside of his grasp. Those dastardly managers, socking wins away for their own nefarious purposes (to give to relievers, I guess?).

Yeah… no. There’s a sampling issue here. Starts are much shorter these days! Very few starts ended with the starter getting pulled in the fifth inning with the lead in the 1970s, but a huge reason for that is that very few starts ended with the starter getting pulled in the fifth inning, period.

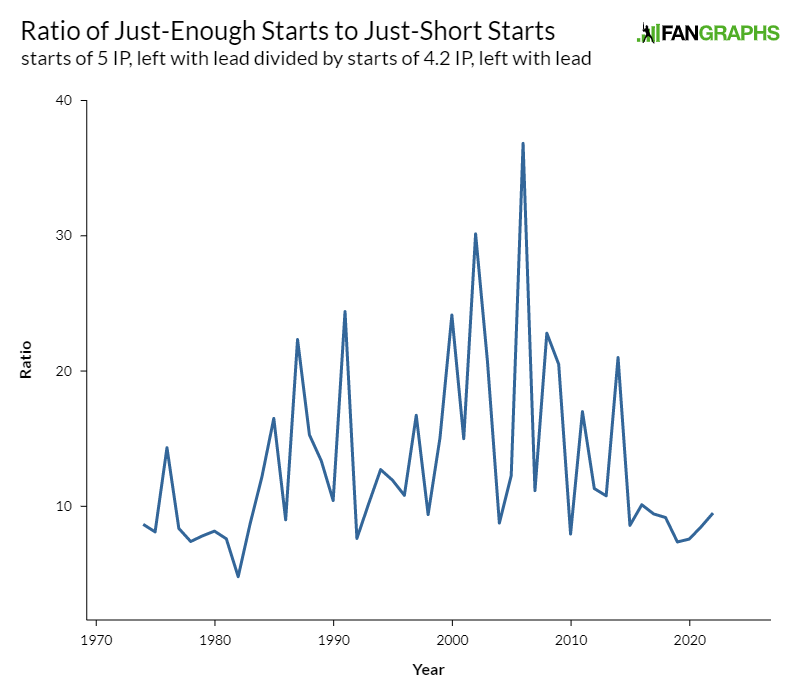

To control for this, I took another number: the number of starts where a starter completed the fifth inning with the lead and then never threw another pitch. In other words, these are starts where the manager could have pulled the starter after 4 2/3, but let them get the last out otherwise. It’s not perfect – it doesn’t include starts where the manager left a starter in, only for them to surrender the lead – but it’s about as robust as I could design a query for. That ratio is far less interesting:

That graph is the ratio between just-enough starts (exactly five innings, leave with the lead) and just-short starts (4 2/3, leave with the lead). Higher means managers are letting pitchers finish the fifth more often. It’s been quite stable over the past six years; in fact, managers have given a higher proportion of starters just enough rope in the past two years. Leaving pitchers in is happening far less than it did in the early 2000s, when the rubber of shorter starts met the road of managers who placed a huge value on wins. But it’s still pretty stable overall. Managers want to get pitchers their wins, even if they’re five-and-dive types.

So is there a grand conspiracy to suppress starter wins in favor of reliever wins? I don’t think so. There are more starts of 4 2/3 innings than ever, and more starts where a pitcher leaves with the lead but short of qualifying for a win than ever, but that’s just because starters are throwing fewer innings these days. Sure, it’s not as fun as the Baseball Illuminati pulling strings and subtly altering arbitration, but it has the advantage of being true.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

A very interesting article, Ben. I have no good way of quantifying it, but I suspect some of it is managers realizing how much more hittable pitchers are the third time through the order. I have no way to research how true that was decades ago. (In Tyler Mahle’s case, as he was the first pitcher to come to mind for me, the numbers say the second time through the order this season!)