The Tigers Found a Diamond in the Rough

Being a fan of a rebuilding team is a tricky line to walk. You want the players to do well, obviously — you’re watching them every day, after all, and it’s only human to root for what you’re watching. At the same time, if they do too well, they’re probably getting traded — how much mental energy should you invest in a player who won’t be on your team in two months? Did that reliever you like find another gear? Cool, enjoy the two lower-level prospects the team will get back for him in a month. Rooting for a past-their-prime star? Well, if they have a good stretch, the team might ship the one face you remember from the good old days out for some salary relief.

There’s one great joy in watching a team that’s in the middle of a rebuild. Whether by accident or design, teams don’t end up trying to retool if they have a ton of solid major league players, which means there’s a playing time void that gets filled by whoever’s available. Minor league free agents and past-their-prime vets? Step right up. Lifetime minor leaguers looking for their first real chance? Someone needs to play third base, so grab a glove. When one of those lottery tickets hits, that feeling makes up for a lot of the bad parts of rebuilding. Here’s a player who has always wanted a chance, and your team gave it to him. If he’s young, he might even be around when the team’s good again, and you, the fan, were there at the beginning. All of this is a roundabout way of saying: Niko Goodrum might be awesome, and the Tigers gave him a chance.

If you haven’t heard of Niko Goodrum before, I can’t blame you. He got a cup of coffee with the Twins in 2017 before signing with the Tigers after the Twins released him, and he delivered a solid if uninspiring 2018 (103 wRC+ in 492 PA, 1.1 WAR) while playing across the diamond. He’s been excellent to start this year, putting up a 132 wRC+ with nearly as many walks as strikeouts while batting cleanup and playing both centerfield and first base. Now you, the sophisticated FanGraphs reader, are no dummy. You know that a 132 wRC+ a few weeks into the season isn’t all that outrageous. It’s above average, sure, but no one’s going to lose their mind over it. What makes me so sure Niko Goodrum is amazing all of the sudden?

Well, first of all, I’m not sure! When Niko Goodrum started popping up on the various screens I use to look for exciting hitters, I mostly assumed I needed better tests. When I saw he was running a 41.7% line drive rate, I chalked it up to small-sample variance and moved on. If I got excited about every career minor leaguer who walked into a few line drives, I’d be calling for a new breakout every day. Look a little closer, though, and something surprising emerges: Goodrum is excelling in ways that don’t look fluky. It’s early, but I think the Tigers have found something.

Let’s start with the basics: Niko Goodrum has shown he can hit the ball hard. He hit 20 balls 105 mph or harder last year, topping out above 110 mph. That’s good territory to be in, especially in only 492 PA — notable names with similar numbers of 105+ mph hits per PA were Matt Carpenter, Jose Ramirez, Kris Bryant, and Miguel Cabrera. That’s important to what we’re talking about here, because if Goodrum didn’t have power to tap into, that would severely limit his upside.

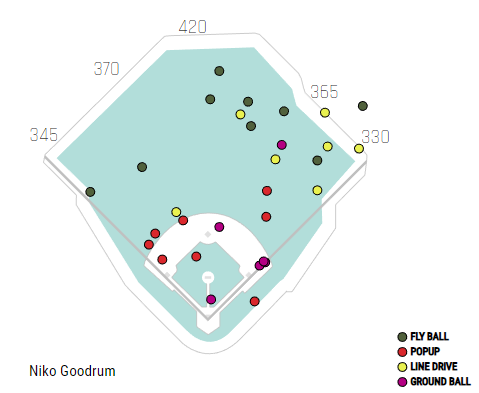

For Goodrum to find a new level, something had to change from last year — a 103 wRC+ is totally acceptable for a utility infielder, but that’s not the season you write a story about. Here’s an interesting fact that might not be immediately obvious, though: all that power is to the pull side. Out of the 20 hardest-hit balls from Goodrum’s 2018, 14 were in the air. Of those fourteen, zero were to the opposite field. He wasn’t using the center of the field, either — I generously counted three as being hit to center, but for the most part his power came at a dead pull.

Just to make sure I wasn’t running into an arbitrary-endpoints issue (what if the balls just below 105 mph all went oppo?), I looked at the 27 air balls Goodrum hit with an exit velocity between 100 and 105 mph. Of those 27, only four were hit opposite field, and all of them were hit while he was batting righty. Given that he’s accumulated all of 6 plate appearances hitting righty this year, I think we’re fine focusing on how he’s done while batting left-handed.

Goodrum has what you’d call pull-only power. He can hit the ball plenty hard, but he needs to pull it to do so. Well, here’s what his batted ball distribution looked like in 2018 as a lefty:

| Direction | Goodrum | MLB Average |

|---|---|---|

| Pull | 41.5 | 40.3 |

| Center | 33.3 | 34.5 |

| Opposite | 25.1 | 25.1 |

Now, wait a second. Here’s a guy who should be trying to maximize his pull side, and he’s essentially John Q Averagemajorleaguer when it comes to his spray chart. That seems suboptimal, and that’s being generous. It’s not as though it’s being driven by the groundballs in the distribution, either. Take a look at his batted ball distribution on line drives and fly balls:

| Direction | Goodrum | MLB Average |

|---|---|---|

| Pull | 34.3 | 30.9 |

| Center | 33.6 | 35.9 |

| Opposite | 32.1 | 33.2 |

Dangit. League average again! For a guy who’s only getting power to the pull side, this isn’t where you want to be.

Let me digress for a quick second — let’s talk about the structure of an analytical baseball article. We’ve covered the promise — Niko Goodrum has changed and he’s good now! We’ve covered the problem — he didn’t pull the ball enough before. Now we’re headed to the reveal — pitchers can’t stand this one stupid trick, and Niko Goodrum used it to hit .300 with power and make $57k a month working from home. That’s how these articles work, and this one is no exception.

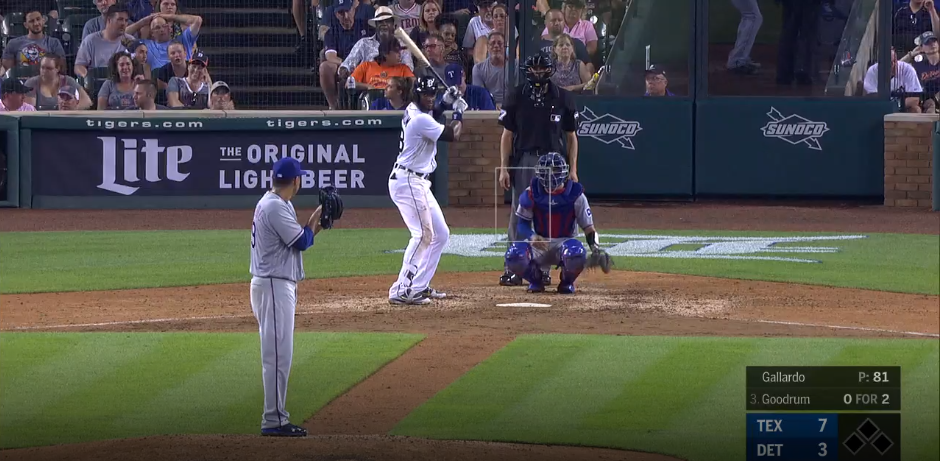

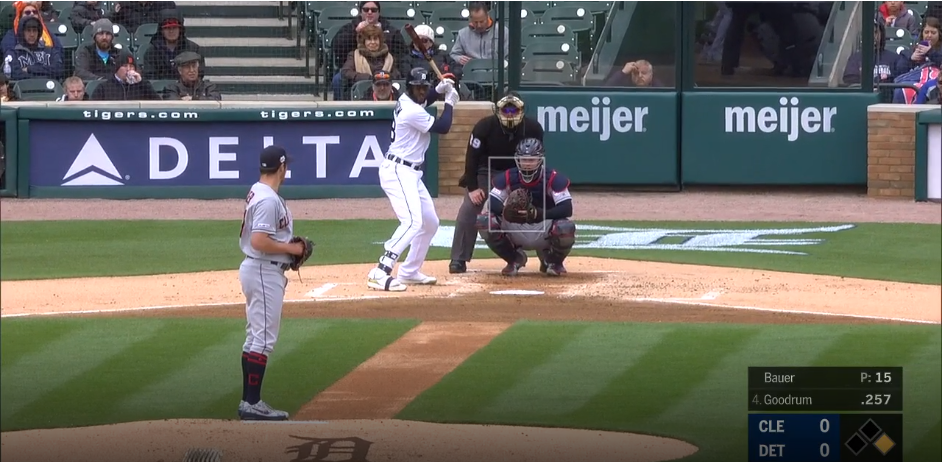

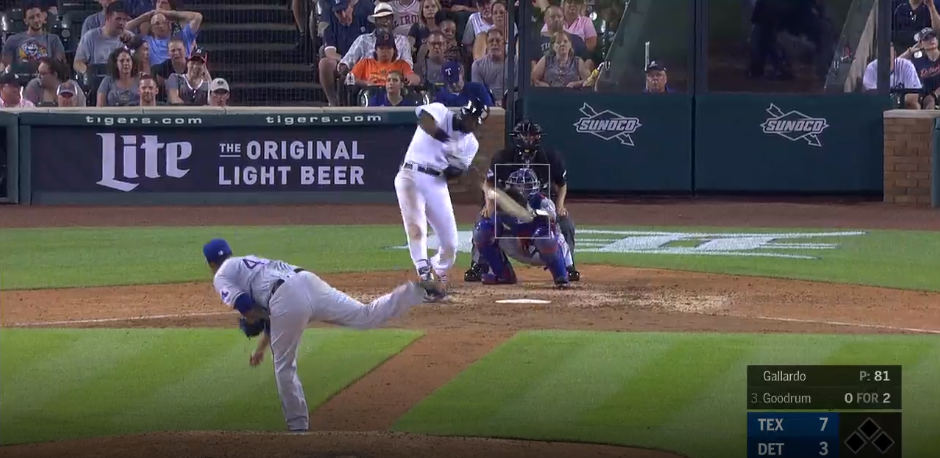

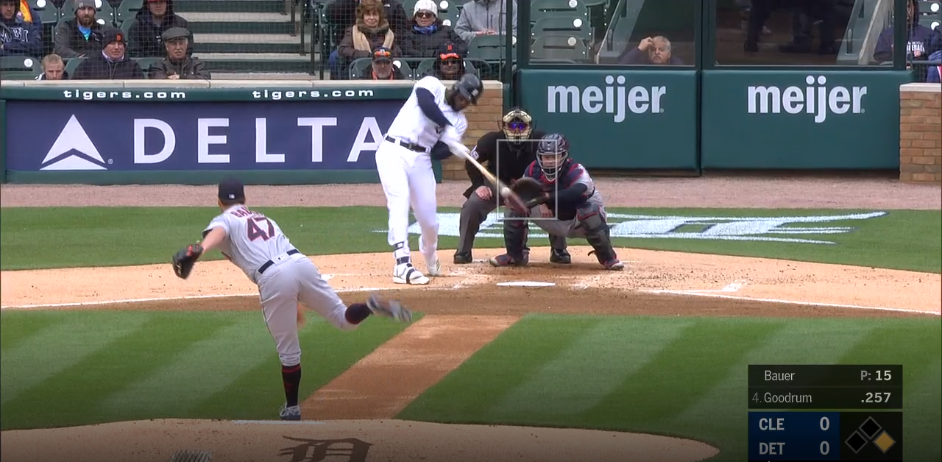

The change, though, isn’t what you’d expect. You might be expecting me to say “swing change.” Travis Sawchik made a cottage industry out of that exact type of article. Jose Bautista made a career out of it, and a great one at that. There’s just one problem: Goodrum didn’t change his swing. Take a look at his setup in 2018 and 2019 (2018 is on top):

Honestly, there’s nothing there. I gave all the footage I could find Zapruder-level scrutiny, and I couldn’t find anything convincing. He hasn’t changed anything at the point of contact either:

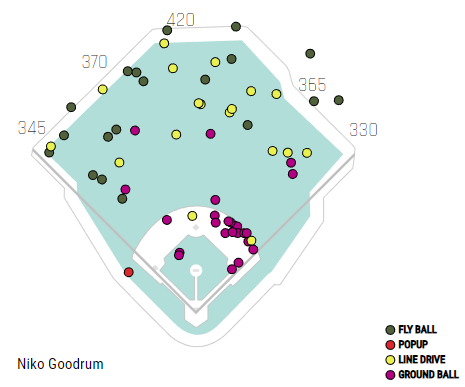

So, okay, no swing change. Despite that exactly-the-same swing, though, something has changed. You remember his league-average batted ball tendencies from last year, don’t you? Take a look at his 2019:

| Direction | All Batted Balls | LD+FB |

|---|---|---|

| Pull | 55.6 | 50 |

| Center | 30.6 | 40 |

| Opposite | 13.9 | 10 |

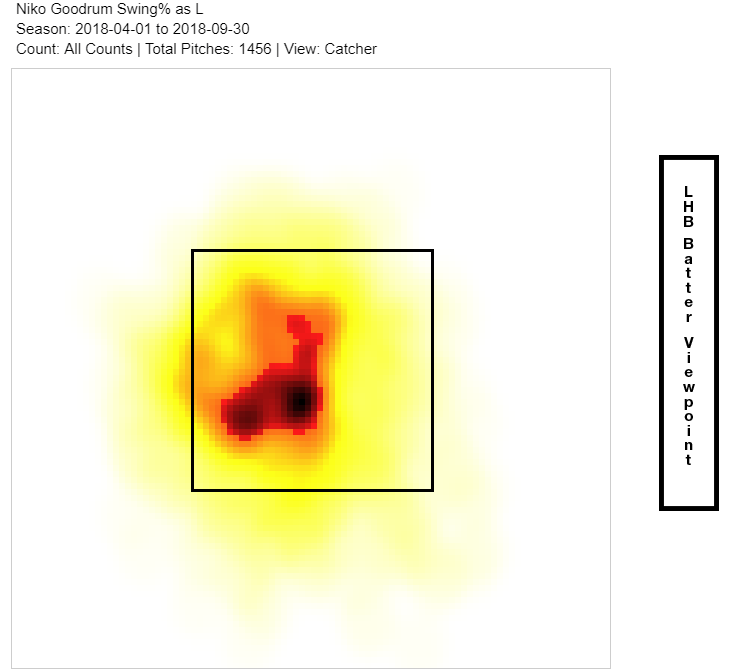

Now, is this a small sample? Absolutely. It’s an extreme move, though, big enough to look purposeful. It’s also a mix that looks like Jose Bautista’s breakout 2010, when he pulled 50% of his batted balls and 45% of his air balls. Additionally, even if Goodrum hasn’t changed his swing, he’s made one key adjustment that’s helped him hit the ball with more authority. Take a look at where he swung in 2018:

Now, that looks pretty normal, but maybe normal isn’t what we want. If anything, Goodrum swung more at pitches away than pitches in, and it’s an adage as old as baseball that pitches away get hit to the opposite field. Take a look at where Goodrum hit the ball when he swung at an inside pitch in 2018:

This is the power that was promised — all right field and center field when the ball gets in the air. This is the idealized Niko Goodrum who put a charge into the ball in 2018. Take a look at his spray chart on swings on the outer third of the plate:

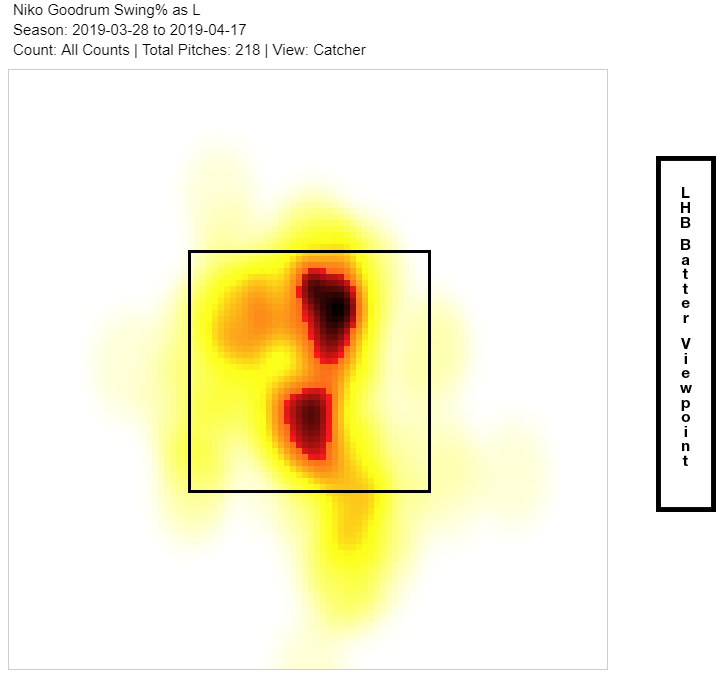

That’s an archetypical all-fields spray chart, and right there you can see the problem. There’s nothing wrong with taking an outside pitch the other way, but it’s not where Goodrum finds power. Astute readers might notice something else — there are a lot more balls in play on outside pitches than inside pitches. That screams for a change, and Goodrum has indeed taken more of his swings to the inside part of the plate this year:

Let’s be more specific than a heatmap, just for completeness’ sake. When Goodrum got a pitch on the outer third of the plate in 2018, he swung 71% of the time. In 2019, he’s down to 48%. That 23% reduction in swing rate seems like it has to be purposeful. Just for comparison, his swings at middle and inside pitches have declined by much less, from 75% to 65%. We’re still in small sample territory when slicing up the strike zone this way, but it doesn’t look like a mistake. That, in a nutshell, is all Goodrum needed to do to tap into his pull power. Lay off the outside pitch, and your batted ball distribution changes just like that.

Goodrum put twice as many balls into play on outside pitches as inside pitches in 2018. This year, he’s put more into play on inside pitches. It’s a sea change, and one that, to me at least, screams intentionality. Changing where you swing isn’t as extreme as changing how you swing, but it isn’t something you do idly. It’s also a change that carries some nice ancillary benefits.

You might have noticed that Goodrum’s swing rate declined both on the outside of the plate and in the strike zone as a whole. I’m speculating here, but it’s easy for me to believe that Goodrum is telling himself to more actively look for a pitch he can pull, which makes him a lot less likely to swing overall. Most pitches, after all, don’t look like a pitch you can pull. A mindset of looking for a particular pitch makes it easier to take anything outside your hot zone, and that shows in his out-of-zone swing rates.

Last season, Goodrum chased pitches outside the strike zone slightly more than average, 33.5%. This season, he’s chasing a sterling 25.2% of the time. That change puts Goodrum in hitter’s counts more often — he’s seeing a higher percentage of 1-0, 2-0, 3-0, and 3-1 counts this year. It’s not rocket science — Goodrum is getting ahead in the count more often, and when he does swing, he’s swinging in an area where he hits the ball harder. That’s how you build a breakout.

Every argument I’ve presented for Goodrum comes with a caveat. It’s a small sample; he’s only putting up a 132 wRC+ right now; he’s a longtime minor leaguer who the Twins just outright cut as recently as 2017. That’s all true! I’m not here to deny any of those facts. There’s another way to look at the narrative, though. A big, toolsy (he has a faster sprint speed than Mike Trout this year) former second rounder found a way to tap into his natural power. It was always there, lurking just below the surface; he just needed to change his swing thoughts to unlock it.

Maybe, in a year, we’ll see that Goodrum was just a flash in the pan. Maybe pitchers will adjust. Maybe it’s all just noise and nothing has changed. I don’t think so, though. I look at him and I see a chance that we’re looking at the next Jose Bautista, only one who can play centerfield and second base with equal aplomb. The Tigers aren’t great this year, and they probably won’t be great next year. They might, just might, have found a guy who will be on the next good Tigers team, though. As a Tigers fan, that’s something to look forward to.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

On the two pictures of his setup, and how he looks at the point of contact, there are two subtle differences. On the setup, his stance is slightly more open. On the following two photos of Goodrum at the point of contact, it appears his stride (right) foot is firmly planted, rather than rolling over, so he his rotating against something firm. It’s possible that being slightly open helped enable this, and it can make for a more explosive hip turn. Or, I’m seeing things, and maybe I need to put my other shoe back on.

Noticed the same thing in his set up – slightly more open. Could be a number of reasons why he decided to make that small change. Very subtle though and I almost wondered if I was really seeing it.