Twenty-Seven Outs to Go: The Nationals Win a Thriller

Outs are a scarce resource. Of all the insights the sabermetric movement has bequeathed, that one looms largest in a game like this, when an entire season hangs in the balance on every pitch. From the second that Yasmani Grandal’s line drive sailed over the right field wall for a two-run homer in the first, the Nationals were on notice:

You are losing. You only have 27 outs to fix it.

A month ago, Brandon Woodruff seemed an unlikely October hero. Not only were the Brewers fading, but Woodruff’s continued absence helped explain why. The righty went down with a strained oblique in late July, and didn’t return until the season’s final weeks. Even when he climbed back on the bump in September, the Brewers were cautious, limiting him to four innings across two late-season starts.

On the big stage, he could not have looked more in form. His heater, one of the fastest in the game on a normal night, reached triple digits and sat just a tick lower. He was amped from the first pitch, and where Max Scherzer tossed a shaky first inning, Woodruff looked settled. In mere minutes, he induced a groundout, a whiff, and a pop up.

Twenty-four outs to go.

For all that is new and unfamiliar in today’s era, baseball remains a game of inches. To wit, let’s consider the two, very long fly balls in the second inning. Leading off the frame, Eric Thames put good wood on a backdoor curve. It wasn’t a bad pitch: indeed Scherzer hit his spot, and he went back to that well to good effect later in the game. This time though, Thames was too disciplined and too strong. He kept his weight back and put the barrel on the ball, lifting it out to deep right center. Scherzer looked shocked, and it did carry farther than I’d have guessed on contact. Ultimately though, the ball left the bat at more than 100 mph, at a near optimal launch angle. Sometimes you tip your cap to good hitting.

In the bottom half of the inning, Kurt Suzuki nearly pulled one back. On the broadcast, it looked like he got all of a Woodruff fastball. But after a season in which seemingly everything hit hard and in the air left the park, we saw something disorienting here: Ryan Braun, back to the fence, settling under a deep fly ball.

Twenty-one outs to go.

Outs are always a scarce resource, but like most commodities, they have different value to different people at different times. In the second, Milwaukee had let their pitcher bat with a runner on first and one out. That was a justifiable decision for a team with a three-run cushion, a cruising starter, and a shallow bullpen.

For the Nationals, down to their final 20 outs, letting Scherzer bat for himself was more questionable. He grounded out, leaving the bases empty for Trea Turner. In another fantastic piece of hitting, Turner caught up to one of the letter-high 98 mph fastballs that Woodruff had blown by everyone else, lining it out into the bullpen to trim Milwaukee’s lead back to two. Should the Nats have hit for the struggling Scherzer, and given themselves an about-20% better shot at having someone aboard for the top of their lineup? Perhaps so.

Eighteen outs to go.

It’s not that the hourglass actually takes on any less urgency as the game creeps along: By the end of the fourth, Milwaukee’s win expectancy was nearly at its highest point of the night. But there are still times where the outs feel like they mean less; perhaps that’s just the human element. In any case, down two runs, the bottom of the fourth never seemed like a particularly urgent moment. If anything, Woodruff’s one-two-three inning looked routine.

Fifteen outs to go.

You can’t nurse a two-run lead for nine innings without a few scares, and the fifth was a legitimately nervy time for the Brewers. Woodruff, on a pitch count and hopped on adrenaline since the first pitch, was lifted for a pinch hitter in the away half of the inning. In his place stood Brent Suter. Suter is a joy to watch. He sits in the mid-upper 80s and leans heavily on a long-breaking cutter. He’s not imposing, he doesn’t throw hard, and he’s pretty predictable. He’s also a goofball who plants trees for fun and encourages his teammates to be more environmentally conscious. He is, in short, the furthest thing from the bearded fireballer we expect managers to trust in big moments. With 15 outs to go and Josh Hader looming, this was the inning Craig Counsell had to ride his luck.

After two quick outs, Washington threatened. Víctor Robles singled to left, and pinch-hitter Brian Dozier reached after smashing a grounder that Mike Moustakas ultimately couldn’t handle. Turner worked a favorable count and got a pitch over the plate but, as often happens against Suter, the cutter ran just far enough in on Turner’s stick to keep it off the barrel; his fly landed harmlessly in Lorenzo Cain’s glove. Counsell could breathe again.

Twelve outs to go.

To this point, Stephen Strasburg’s legacy in Washington has been as much defined by the time he wasn’t on the mound as by his performance on it. The Nationals famously shut him down before the 2012 playoffs, with general manager Mike Rizzo justifying the move by explaining that he wanted to save his arm for the next playoffs and the one after that and many after that too. Ultimately, Washington’s jumpstart campaign short-circuited in the divisional round. The club has since lost two more divisional matchups.

We’ll never know whether Rizzo’s gamble helped Strasburg’s longevity; proving a negative and all that. Regardless, he looked awesome last night. He needed just 34 pitches in his three innings, striking out four while allowing two harmless baserunners.

On the other side, Counsell determined that one inning of Brent Suter was plenty for his tastes, and he summoned Drew Pomeranz in to pitch. Pomeranz looks much more the part of a big-game reliever. He’s a former first-round pick, an All-Star, a guy with a mid-90s fastball and a buckling knuckle curve. A buddy of mine who used to work for the Padres once overheard him boasting that he could eat 50 Taco Bell tacos in a single meal. You could argue that anyone with that kind of stomach must have the fortitude for the middle innings of an elimination game. In any case, the heart of the Nats lineup went down in order.

Nine outs to go.

Milwaukee’s bullpen was not nearly as good this year as it was in 2018. With a deep relief corps, Counsell could afford to use Hader in tight situations regardless of when they arose. If Hader was out of the game in the sixth, there were still plenty of big arms waiting for deployment. That has not been the case in 2019. Corey Knebel missed the entire season. Corbin Burnes has pitched well in tiny bursts and has otherwise been bombed mercilessly. Former All-Star closer Jeremy Jeffress is on the waiver wire.

Down the stretch, Pomeranz filled the void. Traded from San Francisco in mid-July, he pitched brilliantly after moving to the ‘pen, posting a sub-3.00 ERA and whiffing nearly two batters per inning. His reliability made Counsell’s seemingly cavalier decision to let his reliever hit in the seventh — to waste an out — actually look quite rational. Pomeranz validated the skipper’s faith, again retiring the Nationals in order.

Six outs to go.

We probably won’t get another Mariano Rivera. Closers simply don’t stand the test of the time like he did, and his performance in the postseason will almost certainly remain unparalleled. Even after he coughed up the lead in Game 7 of the 2001 World Series, his reputation as the ultimate weapon out of the bullpen remained intact throughout his career, and for good reason.

Hader is the closest thing we have to Rivera these days. There may be relievers with better numbers from one year to the next, but nobody can match the impact his presence in the bullpen makes, or the spectacle he is on the mound: The hair, the delivery, the fastball, the multi-inning role. He is a cheat code, and perhaps the only reliever in baseball worth the price of admission all by himself.

Neither Robles nor Michael A. Taylor appeared remotely comfortable against Hader. Robles fell over backwards on a ball that comfortably crossed the plate; Taylor looked even less likely to make contact. But tonight, Hader wasn’t on the top of his game either. Like everyone else on the mound, he was teeming with adrenaline. Unlike everyone else, he never quite settled. His fastball, always hard and usually located near the top of the zone, was both harder and higher than usual. He managed to strike out Robles, but on a full count, he came too far inside and hit Taylor.

Whether that ball hit Taylor or the knob of his bat is ultimately immaterial. Reasonable people can make the case either way, and the replay evidence wasn’t enough to overturn the call. To the extent Milwaukee fans want to claim that they were jobbed, they’re on shaky ground; had they replay overturned the call, they’d be profiting from a fair bit of luck, as the ball was a mile inside and would have been ball four if only Taylor could have turned away.

After another long at-bat, Turner struck out. It seemed that this would be the pattern: Like a cat playing with a mouse, an amped-up Hader would give hope to his prey by firing a few fast ones out of the zone, only to get his act together in time for the strikeout. With Ryan Zimmerman at the plate, in for Adam Eaton and up for perhaps his last time as a National, the pattern seemed to repeat itself. But Zimmerman’s broken-bat bloop was hit just well enough to reach the outfield grass in front of Cain. Broken bats have been the bane of Hader’s season; the game has a way of defying even its most titanic figures. An Anthony Rendon walk loaded the bases.

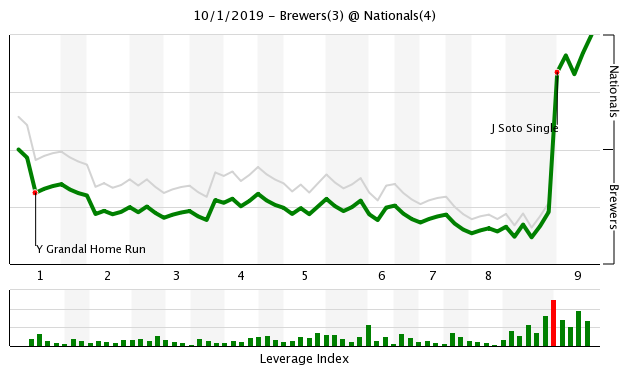

You know what happened next. Baseball’s best teenager met baseball’s most dominant arm, and the kid won. Soto’s line drive to right was always going to plate two, and when Trent Grisham overran the ball on his way to field it, a third run scored easily.

It’s helpful to remember that Washington would have been in the driver’s seat at this point anyway: With a deadlocked game, more outs left, a tiring Hader on the mound, and an unbelievably loud crowd on hand, the Nats would have had a higher WPA for the first time all night whether or not Grisham had fielded the ball cleanly. Still, there’s no way to sugarcoat it: That was as devastating of an error as we’ve seen in some time. Soto ran into an out between second and third to end the inning, and that seemed appropriate; it would have been cruel to keep Grisham on the field.

Three outs to go.

I’ll be honest: Once Counsell got the ball to Pomeranz, I never expected the out countdown to turn on Milwaukee. Nor would I have expected Dave Martinez to trust Daniel Hudson with the ninth inning, particularly with Thames due up and Ben Gamel set to bat fourth in the inning; this seemed like a job for Sean Doolittle.

Ultimately though, Hudson slammed the door. He retired Thames and pitched around a one-out single from Cain. Gamel deserves a footnote: With all the pressure in the world on him, he muscled a hard line drive nearly 400 feet to deep center. Had the ball been in the alley, Gamel could’ve wound up on third in a tied game — with Grisham on deck to be the hero, no less.

For Hudson, jubilation: He had a starring role in the biggest game in Washington’s franchise history, perhaps the apex of a rollercoaster career in which he has twice been sidelined by Tommy John surgery.

For Grisham, it just wasn’t meant to be.

Mike Rizzo is still very much employed by the Nationals. Nice recap regardless.