What’s Wrong With José Berríos?

Here’s a thing that you could say about José Berríos: he’s been a lousy pitcher this year. I don’t even think he would argue with you on that one; after signing a seven-year, $131 million deal with the Blue Jays, he’s having comfortably his worst season in the majors. His 5.28 ERA is more than a run higher than his career mark coming into the year despite the declining offensive environment. He’s striking fewer batters out and giving up home runs at an alarming rate. Whether you’re talking about advanced or standard metrics, new school or old school, it’s been a disaster of a year.

Here’s another thing you could say about Berríos: he’s a solid pitcher who’s sticking with the approach that got him here in the first place. If you thought he was good last year — and you probably did, given that he put up a mid-3s ERA in both Minnesota and Toronto with the peripherals to match — you’d expect him to be good again this year. He’s not losing velocity. He didn’t change his pitch mix. He didn’t suddenly lose command of the zone. What the heck is happening here?

Before we go any further in this investigation, I’m going to spoil the conclusion a little bit: I don’t know the answer. I don’t think there’s an obvious answer at all, in fact. If there were, I’m fairly certain the Jays would have figured it out by now. Whatever’s ailing Berríos, it’s somewhere on the margins.

More specifically, it’s something going wrong with his four-seam fastball. If you take a look at run values by pitch type, that much is obvious:

| Year | FF | SI | CU | CH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | -7.6 | 2.7 | -6.1 | -5.9 |

| 2017 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 4.8 | -3.5 |

| 2018 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 2.3 | -4.6 |

| 2019 | 7.2 | 4.8 | -1.8 | 0.3 |

| 2020 | -6.9 | 3.4 | 6.6 | 1.2 |

| 2021 | -3.0 | 13.7 | 1.5 | 4.1 |

| 2022 | -16.8 | 2.4 | 3.6 | -4.2 |

When Berríos has been at his best, he’s gotten acceptable production out of his four-seamer as a setup pitch and phenomenal results when he throws his sinker. Thanks to his release point, he’s never been the type to blow four-seamers past hitters up in the zone; his version of the pitch has as much tail as ride, which means it’s less climbing over opposing bats than boring in on them.

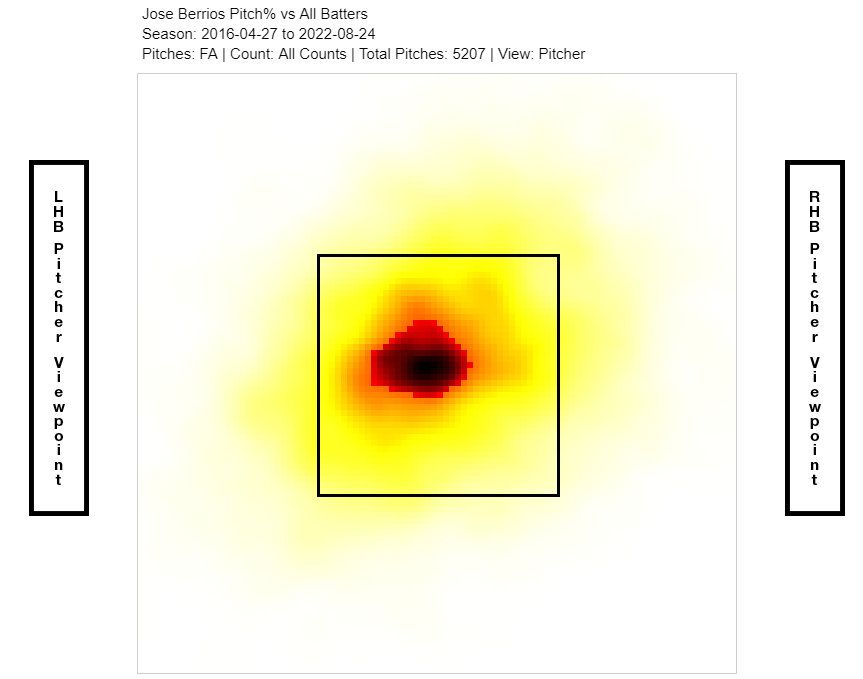

That wasn’t an existential problem in the past. A subpar individual pitch can still be useful, whether mitigating a platoon disadvantage, providing help for specific counts or game situations, or merely giving a hitter more pitches to think about. Berríos throws his four-seamer more when he’s behind in the count than ahead, and more to lefties than righties. In other words, he uses it to escape from bad situations. The sinker is used similarly, but make no mistake: the two are different pitches. Here’s where he throws the four-seamer:

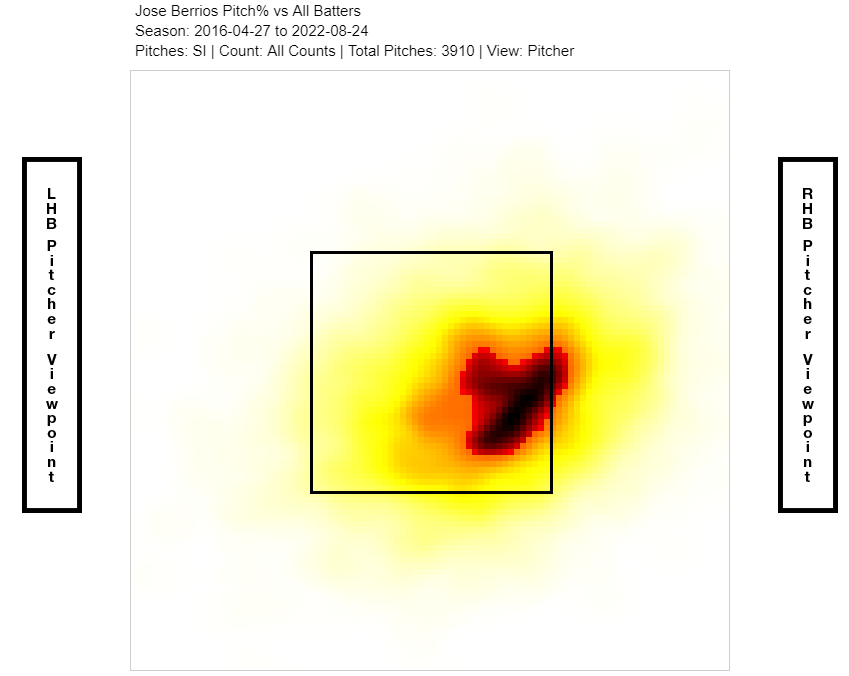

And the sinker:

From 2017 through ’21, that four-seam plan worked well enough. None of the pitch’s raw measurables were particularly impressive; as I already covered, the shape doesn’t lend itself to missing bats up in the zone. That meant below-average swinging-strike, whiff, and in-zone contact numbers. That all sounds bad, but remember, he mostly used it in situations where a swinging strike would be less helpful than normal: down in the count or against batters who had the platoon edge.

When you start from behind, allowing contact isn’t necessarily a bad thing. In aggregate, batters put up a .273/.497/.470 line after getting ahead in the count 2–0, good for a 179 wRC+ and .424 wOBA. When batters put Berríos’s four-seamer in play from ‘17 to ‘21, they managed a a .417 wOBA. That’s if they put it in play; they took plenty for strikes and fouled plenty more off. Sure, everyone would like to have an unhittable four-seamer like Jacob deGrom, but there’s value in a reasonable off-ramp.

That off-ramp has turned into a car crash this season. Opposing hitters are absolutely tattooing the pitch, batting .441 when they put it into play and slugging .795, which works out to a .528 wOBA. If that were a single batter’s line, he’d have the fourth-best production against fastballs in the majors this year, better than Paul Goldschmidt or Mike Trout. That’s as bad as it sounds; you probably shouldn’t throw a pitch if it turns your opponent into an MVP candidate.

Is it bad luck? Bad luck is a great way to hand-wave pitching problems. “Oh, sprinkle a little BABIP regression on it, he’ll be back to normal in no time” is a time-honored way of papering over any problems. But I don’t think that’s the case here. A full third of the four-seamers Berríos has thrown this year have been over the heart of the plate, the highest mark of his career. That number has been climbing over time; increasingly, he’s resorting to floating one in there to get back into the count. It’s worked from a limiting walks perspective, but it’s no surprise that opponents have increasingly clobbered his four-seamers. Filling the zone isn’t always a bad thing, but it’s a bad thing when you’re throwing a lot of those pitches right down main street.

It’s not that hitters are suddenly tagging piped Berríos four-seamers more; in fact, their production when they put a middle-middle four-seamer into play has been quite stable over the years. But here’s something scary: 17.3% of all the batted balls he’s allowed this year have been the result of four-seamers over the heart of the plate. That compares to 13.8% in his career before now. That’s an extra 15 batted balls that opponents are hitting under optimal conditions, and that really matters. When batters have put the ball in play on any pitch other than a middle-middle four-seamer against Berríos, they produce a .344 wOBA. When they put middle-middle four-seamers into play, that jumps to .455. That’s twice the gap that pitchers see in aggregate; Berríos’s four-seamer is particularly prone to getting launched, likely due to its unremarkable shape.

What’s so weird about all of this is that Berríos has a perfectly good fastball to use! His sinker might actually be his best pitch; he gets a ton of arm-side run on it, which makes for uncomfortable swings from righties and hey-how’d-that-get-here called strikes against lefties. Over the course of his career, it’s been his best pitch, and as an added benefit, it sets up his wipeout breaking ball thanks to their divergent spin and movement profiles.

If I had Berríos’s sinker and curveball (some systems call it a slider, but whatever you want to call it, it’s excellent), I’d try to throw them as often as possible. He only throws them a combined 56% of the time, though. There’s a lot of dead air being filled with his four-seamer and a fringy changeup. Sure, variety is the spice of life, but if you’re getting demolished on one fastball but dominating hitters with the other, I know which one I’d throw more often.

Batters are catching on to Berríos’s strange fastball preferences. They’ve never swung more often at his in-zone four-seamers. They’ve never swung less often at his in-zone sinkers. So long as he’s offering up juicy pitches to hit, batters will continue down that road. If I were game planning against Berríos, I’d start the report with a giant bold note about attacking his weakest pitch, the one that he throws far more than he should and in exploitable locations.

Would rectifying his bad season be as easy as cutting his four-seam usage in half? It sounds reductive, but I think it might do the trick. It’s not clear what he’d do to replace those pitches, exactly; his changeup isn’t scaring anybody. But heck, why not just throw more sinkers? Toronto finally has a great defense to put behind him, the seventh-best infield defense per Statcast. Feed them! All the other plans I could think of — changing fastball shape, locating better, adding a better changeup — are much harder than just changing up your pitch mix.

Could this plan backfire? Absolutely. It puts more of a premium on control, because batters swing less frequently at his sinkers. If I were Berríos, I’d be willing to stress my control, though; he’s only walking 5.7% of his opponents this year, and he’s been a consistent strike-thrower throughout his career. Getting into a strike zone contest with Berríos will end poorly for plenty of batters, but getting into a fastball-clobbering contest will frequently end with a leisurely stroll around the bases.

At the end of the day, the most important part of pitching is keeping runs off the board, and Berríos hasn’t been up to the task this year. But there’s room for optimism, because for the most part, he still possesses the tools that made him an effective starter for years. The Jays and Berríos mostly know what’s wrong. They’re trying to work on his fastball locations. But I wonder if they could skip that entirely and just find a new pitch mix that works better.

Note: All statistics in this article are through games of 8/28. Berríos made another start last night and took my advice, throwing his four-seamer only 16% of the time. He still gave up ten hits (though no home runs) in 5.2 innings.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Well at least they saw this disaster in the making and grabbed Luis Castillo or Frankie Montas before the deadline…oh wait

(Of course it’s hard to win regardless of who’s pitching when you score 3 runs in an entire series at home against the shitass Angels…that’s an entirely different disaster than the one of Berrios’s making)