Yandy Díaz and the Groundball Revolution

If you’ve followed FanGraphs the past few years, you know the Yandy Díaz story by now. As an Indians prospect, his contact and on-base abilities marked him as a potential major league contributor, but his physique hinted at more: Díaz excelled despite a plethora of groundballs, and he also had elite bat speed and exit velocity numbers at times. If he could just aim up a little more, the thinking went, he could be the next launch angle success story.

When the Rays acquired him in a trade before the 2019 season, it wasn’t hard to connect the dots. The Rays acquired an already-usable player with a fixable flaw? We’ve certainly heard that story before. Indeed, Díaz spent 2019 putting balls in the air at a rate he’d never approached before. His fly ball rate spiked, his groundball rate dropped, and he hit double-digit homers for the first time in his professional career.

All of those balls in the air made Díaz a different hitter, but they didn’t change the core of his approach at the plate: wait patiently for a pitch he liked, then try to hit the snot out of it. As FanGraphs alum Sung Min Kim detailed, he mostly accomplished it without a swing change; he simply focused on finding pitches to drive rather than spraying grounders.

The evidence was there if you wanted to look for it. His air pull rate, the percentage of line drives, pop ups, and fly balls that he sent to left field, jumped significantly. At the same time, he started hitting fewer grounders; his GB/FB ratio dipped to heretofore unseen lows:

| Year | GB/FB | Air Pull% |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 3.13 | 9.8% |

| 2018 | 2.29 | 9.5% |

| 2019 | 1.59 | 18.9% |

It’s worth noting that neither of these rates look extreme. The league as a whole pulled 30% of its balls in the air in 2019, and hit 1.2 grounders for every fly ball. Díaz wasn’t going full José Bautista; he was simply heading towards being a normal-tendency hitter with abnormal strength. Only two players in all of baseball — Ryan Braun and Shohei Ohtani — managed a higher isolated power than Díaz while hitting more grounders per fly ball. The implication seemed clear: Díaz was slowly figuring out how to best harness his power, and if he could just pull a few more balls in the air, he might level up again.

Good news! Through 124 plate appearances this year, Díaz has leveled up. He’s managed a 137 wRC+, good for 0.8 WAR, which puts him on a 4 WAR pace in a full season. That’s All-Star production, and it comes from a guy we knew could do it all along. There’s just one tiny problem:

| Year | GB/FB | Air Pull% |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 3.13 | 9.8% |

| 2018 | 2.29 | 9.5% |

| 2019 | 1.59 | 18.9% |

| 2020 | 5.00 | 3.3% |

Uhhhhh… what? That’s downright baffling, and it might undersell how rarely Díaz is pulling the ball in the air. He has exactly one pulled air ball this year, and you might not consider it an air ball:

There are a few weird things about this one. First, it’s pretty close to not being an air ball; one degree lower, and Statcast would have classified it as a groundball instead of a line drive. Second, that’s José Peraza pitching in an 11-run blowout. Peraza is a shortstop. That’s not the kind of pull power we were all hoping for.

Díaz’s excellent batting line isn’t driven by power. In fact, his power is the only thing holding him back. He’s hitting .297/.427/.386, and not a single hitter with a higher wRC+ than him has a worse isolated power mark than his .089. The man whose biceps make sleeves cry is subsisting on slapped grounders and walks.

If you’ll recall from his prospect origin story, Díaz has always had an excellent batting eye. He’s truly leaned into it this year, swinging at only 35% of pitches he sees and only 15.2% of pitches outside the strike zone. That’s the third-lowest rate in the game, behind only Cavan Biggio and Carlos Santana. He’s also always had excellent contact skills, and that’s continuing as well; he has the 16th-best contact rate and fifth-best out-of-zone contract rate in all of baseball.

Of course, making more contact wasn’t the change people expected out of Díaz. He was supposed to make more selective contact. In 2019, he saw 171 pitches in the upper third of the strike zone and swung 73.1% of the time. That’s his happy zone, the place where he generates extra bases at a ludicrous rate:

If you ignore the lower inside corner, which looks mostly like a sample size artifact, the story is clear: he clobbers high pitches. This year, however, he’s aiming lower; he’s swung at only 59.6% of pitches in the upper third. That’s not a big drop in the context of his overall swing rate — he’s swinging 10% less often at pitches in the strike zone anyway — but it’s a pretty clear cause. Less swings in a power hot zone means less power.

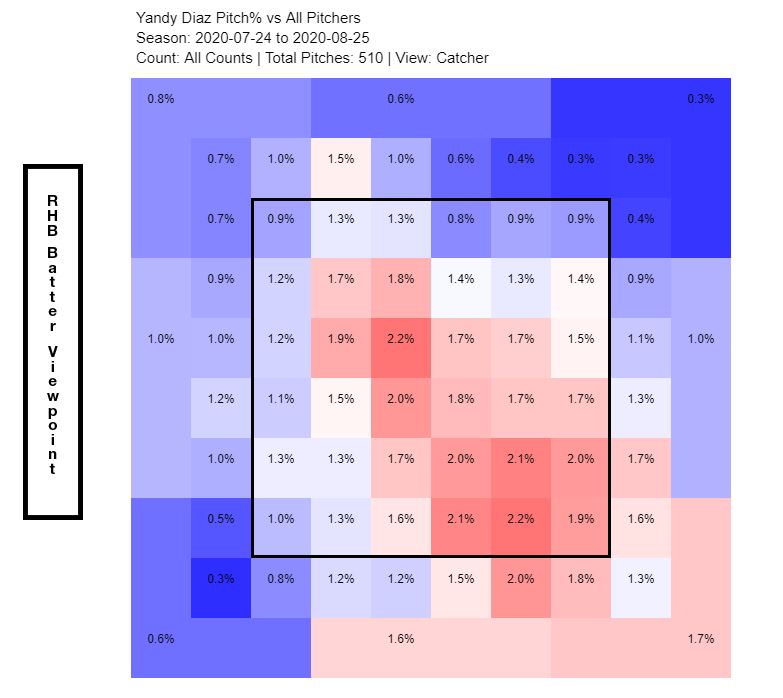

Of course, batting isn’t a one-sided endeavor. You can only swing at the pitches that you see, and pitchers aren’t giving him anything to hit. Take a look at the low and away cluster he’s facing so far:

You can hardly help hitting a grounder if you swing at those pitches. It’s not a matter of swinging more at them — he’s swinging eight percentage points less often at the low and away stuff this year. That’s simply not a ball that’s easy to lift, particularly for a high ball hitter like Díaz. Righties put those balls into the ground roughly half the time, and Díaz sits at more like 60%. Face a ton of those pitches, and you’re going to be hitting for less power.

What’s the proper counter to those pitches? Shooting the ball the other way, more or less. It’s hard, phenomenally hard, to produce pull power in the air on a pitch low and away. Physics is cruel that way. In his career, in fact, getting pull-happy on low and away pitches has been a bad move relative to staying open and hitting them to right:

| Direction | wOBACON |

|---|---|

| Pull | .344 |

| Straightaway | .291 |

| Opposite | .426 |

There’s a dirty secret about grounders: even in the absence of a shift, pulled grounders are a lot less valuable than those hit to the opposite field. On balls hit at 15 degrees of launch angle or lower (to deal with those pesky balls like the one Díaz hit against Peraza), going oppo is significantly more likely to find a hole. That’s true even for righty batters facing an un-shifted defense. Here’s a table of wOBA on balls hit 15 degrees or lower by righties facing a normal defense over the past two years:

| Direction | wOBACON |

|---|---|

| Pull | 0.311 |

| Straightaway | 0.3 |

| Opposite | 0.48 |

And while Díaz is hitting more grounders, he’s hitting them to the opposite field. No one in baseball bests him in the percentage of his 15-degree-and-lower balls sent the opposite way:

| Player | Oppo% |

|---|---|

| Yandy Díaz | 41.3% |

| DJ LeMahieu | 37.3% |

| Danny Mendick | 35.3% |

| David Bote | 32.1% |

| Austin Romine | 29.0% |

| Chris Taylor | 26.8% |

| David Fletcher | 25.3% |

| Travis d’Arnaud | 23.1% |

| Anthony Rendon | 22.9% |

| Nico Hoerner | 21.9% |

This is a completely new skill for him; before this year, he only went the other way on 17.3% of his low-angle batted balls. This year, however, he’s wearing out the opposite side of the field. Is that a skill? I did a quick check, because honestly, I had no clue. I took every right-handed batter with at least 100 relevant batted balls in both 2018 and 2019, then divided their 2018 opposite field rates into quintiles. There was quite a spread:

| Quintile | 2018 |

|---|---|

| 1 | 18.6% |

| 2 | 14.5% |

| 3 | 12.4% |

| 4 | 10.4% |

| 5 | 7.5% |

And it wasn’t a fluke. The spread carried over to 2019. The batters who hit the most opposite-field grounders in year one still hit more than average in year two, even if their rate declined somewhat:

| Quintile | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18.6% | 15.4% |

| 2 | 14.5% | 13.8% |

| 3 | 12.4% | 12.4% |

| 4 | 10.4% | 10.7% |

| 5 | 7.5% | 7.9% |

In other words, going the other way on grounders seems to be a skill batters can truly possess. That’s not to say it’s guaranteed to continue, or that this is even what Díaz should be doing. It certainly doesn’t mean he can keep up his current stratospheric rate. At present, though, it feels like a chess match. Pitchers learned last year that Díaz wants to crank the ball in the air. They countered with a straightforward plan: throw it to a place he can’t pull.

Díaz’s counter to that counter is, for now, holding the day. He’s doing his best to wait for a pitch to hit — with less than two strikes, he’s spitting on those pitches, swinging only 36.1% of the time — righty batters swing 55.2% of the time in similar situations. When the count reaches two strikes, he’ll defend by trying to punch the ball the other way — he’s swung at 25 of 27 such pitches on the year, 92.6%.

For pitchers, it hasn’t been a sustainable equilibrium. They’ve found the zone on only 43.4% of pitches per Statcast, the lowest zone rate of his career by four percentage points. You can’t beat Yandy Díaz without coming into the strike zone, because he’ll just walk, and that’s exactly what’s been going on.

I’m not quite sure how this dance will end. Díaz doesn’t have much incentive to change what he’s doing at the moment; though his production looks bizarre, a .426 OBP will play no matter how you get to it, and it’s not as though he’s running a wild BABIP to get there. Pitchers have to do something different; you can’t keep throwing the ball out of the strike zone at this clip to a patient hitter and expect to succeed.

When pitchers either find the zone again or revert to their previous patterns, giving him more inside and high pitches to hit, he’ll have to adjust again, prove he can succeed without an 18% walk rate buoying him. Whether he can make the change or whether pitchers win, though, it’ll be a fun subplot to watch. Díaz is waging a one-man campaign to make grounders work for the offense, with a little help from his opponents. It can’t last, but the uncertainty over whether he’ll crash down or rise up is delightful.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Interesting player uses One Weird Trick to succeed— this is my favorite type of Ben Clemens article

Defensive Shifts Hate It!!