The New and Exciting Rays Slugger

If you’re talented enough to make it to the majors, you often have had to make a series of adjustments to maximize your potential and survive in the league. If you are really talented, knowing yourself and being open to changes can really put your name on the map. Yandy Diaz is really talented. We’ve raved about his tools and uber-muscular physique. The Rays are giving him a starting opportunity pretty much every day, which is exciting; they have to be excited by the return as well.

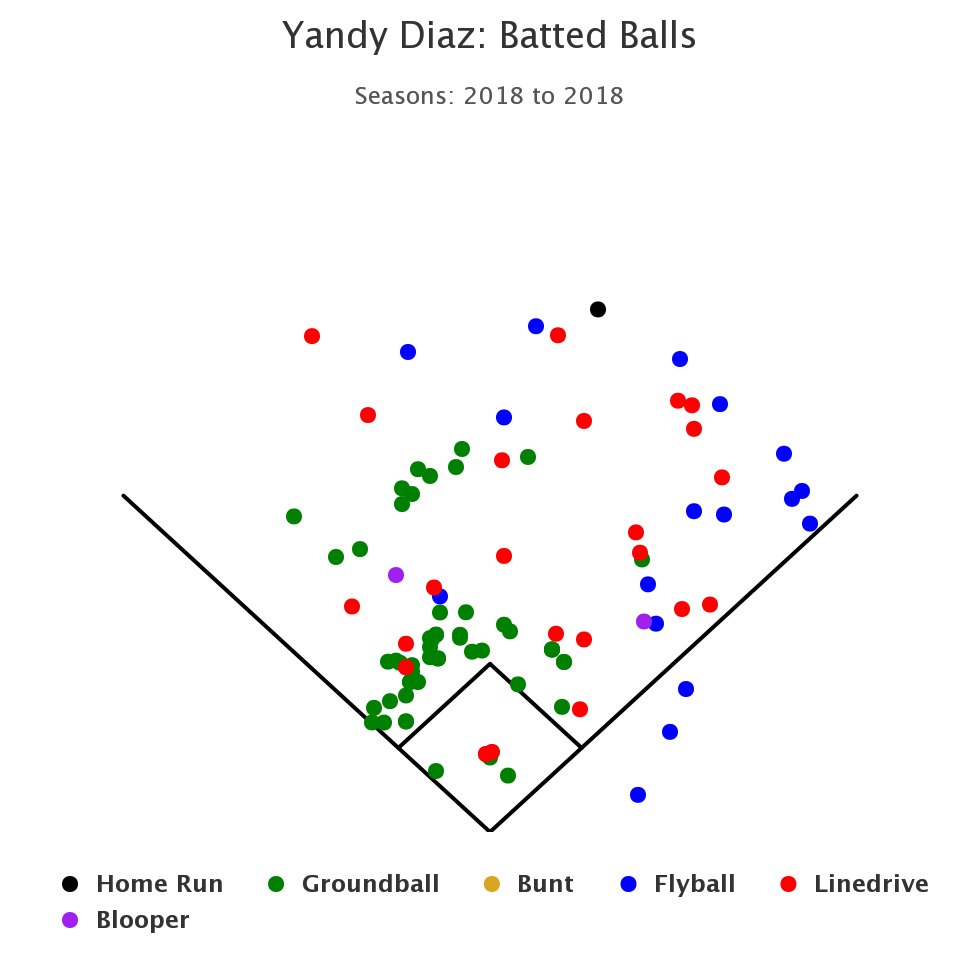

So far in 2019 (all statistics are as of April 9), Diaz has turned in a .308/.386/.615 line with a 183 wRC+ and three home runs. The Rays have gotten what they have hoped to get from him in the first 10 games. Diaz’s underlying numbers — not only this year, but also from the years prior — testify to his strength. In 2017 and 2018 with Cleveland, Diaz hit for average exit velocities of 91.5 and 92.1 mph, respectively, which was well above the league average of 87.4 mph. He also was an extreme ground-ball hitter. In 2018, his launch angle was 4.4 degrees, much lower than the league average of 10.9. As a result, 53.3% of his batted balls last year were grounders, which, if he had had a qualified number of at-bats, would have ranked in the top 10 in the entire league.

Because Diaz has such a low launch angle, all he has to do is swing up, elevate, and celebrate, right? It’s not exactly that simple. In midst of baseball’s fly-ball revolution, we have seen instances of players actually trying to swing more “level.” Last year, Jeff Sullivan noted Joc Pederson and Kyle Schwarber’s adjustments. Kris Bryant also saw strides in his production after adjusting his swing to spend more time in the zone. We have many other success stories in which hitters benefited from, well, learning to lift the ball. The point is that the equation isn’t so simple. If it were, every hitter would be enjoying success by altering their swings in the same way. It is a league-wide trend, for sure, but there are things that work for some and don’t for others.

Diaz is a special case though. Because he is such an extreme groundball hitter who can also hit the ball hard, it could be worth it for him to experiment with different approaches to become his best self in the majors. It might not work out, of course. But because of his above-average exit velocity, it could pay off quite handsomely. Look at his home run versus Gerrit Cole from earlier this season.

Readers, that was smoked. It traveled for a 112.2 mph exit velo with a distance of 420 feet. It’s been documented that Diaz can hit for average (he had a .311/.413/.414 career line in the minors and hit .312/.375/.422 with Cleveland last year), but what raised my eyebrows were his 2019 power numbers. Increased power production is usually a product of some sort of change. Think Jose Bautista with his leg kick and Justin Turner with Doug Latta.

As of this writing, Diaz has had 30 batted ball events in 2019. That is quite a small size. At the same time, the results are noteworthy enough to dig in. Both can be true. Looking at his data, one thing really jumped out to me in particular:

| LD% | GB% | FB% | Pull% | Cent% | Oppo% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 22.1% | 59.0% | 18.9% | 24.6% | 39.3% | 36.1% |

| 2018 | 23.3% | 53.3% | 23.3% | 28.9% | 38.9% | 32.2% |

| 2019 | 14.7% | 52.9% | 32.4% | 47.1% | 32.4% | 20.6% |

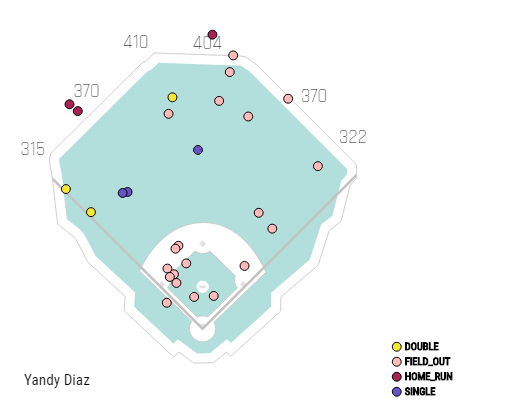

He’s been pulling the ball a lot more – a bit less than twice his 2018 rate. To emphasize visually, here are his 2018 and 2019 spray charts.

2018:

2019 (courtesy of StatCast):

While he has managed to line and lift the ball to center field and right field, there are more batted balls that ended up on his pull side — especially the ones that ended up being extra-base hits. That is an interesting change. He went from a guy who mostly lined balls to center and right field into a pull hitter with better power numbers.

Many hitting coaches, driven by conventional wisdom, would preach spraying the ball all around the field to avoid being a one-dimensional pull hitter. However, guys like Alex Bregman and Jose Ramirez, two of the top 10 pull hitters of 2018, were in MVP conversations last year thanks to their hitting prowess. There’s also the actual 2018 AL MVP, Mookie Betts, who took his production into a new echelon by pulling the ball more. It may be impossible to predict the future, but one can try to forecast it, and I can’t help but wonder if an increased pull tendency can play a part in sustaining Diaz’s current performance.

I’m not sure if that has correlated to anything else in his early statistics. He’s hit fly balls more frequently. His Statcast barrel percentage is up from 4.4% in 2018 to 10.0% this season. His strikeout rate is down by 15.8% to 7.9%. His walks are also up from 9.2% to 13.2%. Most of these are encouraging trends. Some of these could probably be affected by other factors. He could have more familiarity against major league pitching after getting more reps. It could be simply a case of a small sample. Things could look different once the league has a better book on how to face him. Because it’s still quite early in the season, there are more question marks than certainties.

I wondered if it showed in his swing. It’s hard to examine bat paths on regular television feed. There might be hitting connoisseurs out there who can point out the most subtle hints in a swing, but I’m not one of them. That said, here are two Diaz swings:

2018:

2019:

Admittedly, it’s not a perfect comparison; the first GIF is of a 93 mph fastball and the second features a 84 mph offspeed pitch. Diaz does something different to these two inside pitches — the 2018 Diaz lines it to the right field for a double and the 2019 Diaz deposited it into the left field seats for a two-run homer. I think the difference here, seen with a naked eye, is the intent. The 2018 Diaz is trying to square it up forward to put the ball in play. The 2019 Diaz looks like he wants to try to hit it far. He did say, in an interview with Juan Toribio of MLB.com, that he’s trying to elevate more. That intent is suggestive of an approach.

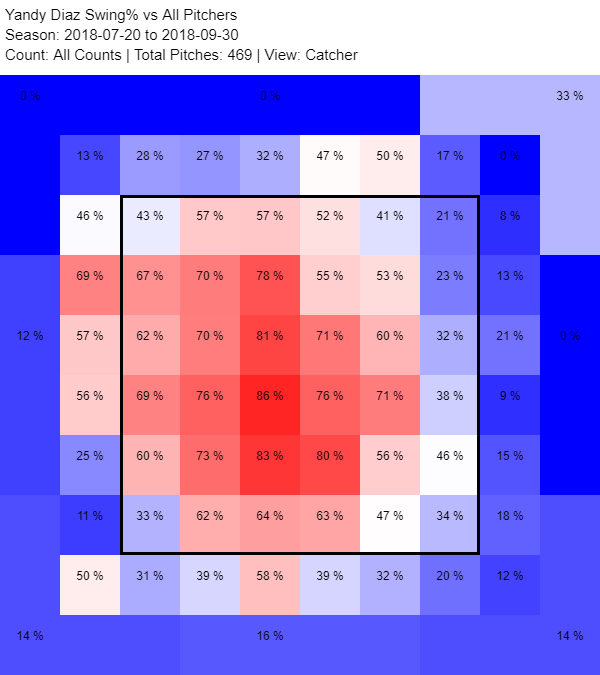

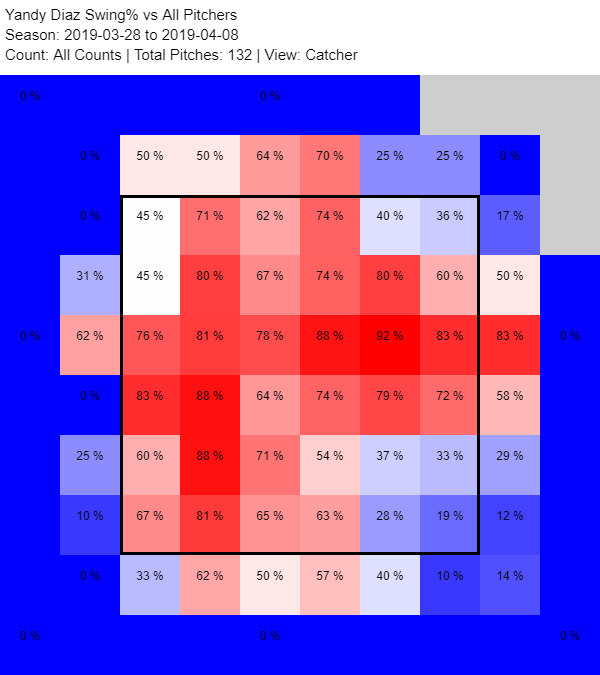

Other than that, it’s hard to find a difference. The stance is basically the same. The timing trigger mechanism is also quite identical. Diaz could just simply be telling himself to pull the ball and finish it harder while employing the similar mechanics. Or, here’s another theory: he’s being more aggressive on inside pitches. By hitting them more frequently, even with same swing and approach, he’s getting more base hits that end up on the pull side. This might be a more plausible trend to gather from this small sample size, because he has, as a matter of fact, been swinging at more inside pitches:

2018:

2019:

It seems that maybe Diaz is going with being aggressive on inside and middle-height pitches. It’s possible that he may have identified those areas as his favorite spots. Or he may have gotten juicier pitches in those areas in this short span of time. My theory here is this: because Diaz has his hands placed a bit low in his stance, it’s easier for him to be quicker on pitches at that height. It’s like how Nelson Cruz, a hitter with hands held up high, can hit high pitches pretty well. For now, that’s just my guess.

I am interested in how Diaz will keep the numbers up for the rest of the season. It’s hard to say because he doesn’t have as much track record in the majors. He does get a little benefit of the doubt because of his good hitting track record from the minors and his ridiculous strength. He is 27 years old, but he wouldn’t be the first late-bloomer in major league history. There aren’t a lot of things as valuable as hard-hit, pulled line drives and big flies. More of them is a good thing, and that’s how it has trended so far this season.

Sung-Min Kim writes for River Ave. Blues, and has written for MLB.com, The Washington Post, Baseball America and VICE Sports. Besides baseball writing, he is also passionate about photojournalism and radio broadcasting. Follow him on Twitter @sung_minkim.

Great article, Mr. Kim – thank you for the graphics.

As far as any swing changes in the at-bat comparison (I do grant that I’m nowhere near an expert), it looks like he closes off more with the toe-tap in 2018, and he lets the ball travel pretty deep into the zone before contact. To me, that’s indicative of a clear intent to aim toward right/right-center; it’s almost an inside-out swing a la Jeter.

The 2019 swing, though, definitely looks like he’s trying to The Natural the ball (i.e. the string trailing the ball sailing); he doesn’t close off as much with the toe-tap and his hips explode outward toward left. He’s much more in front of the ball too; it doesn’t get very deep into the pocket before contact.

The swing arcs themselves look fairly identical to my naked eye, but the intent behind the swings is much different – I think that’s where the real change is.

I see his top side is much more open in 2019, allowing him to turn more quickly through the zone and use his power. The ball isn’t getting as deep on him, but like yourself, I am by no means a swing expert. That’s just what my eyes show me from two swings.

Yep, his top side opening up is a function of that hip torsion; he’s clearly trying to target left field.

To me, his swing follow through looks really very different. In 2018 the bat is closer to vertical at the end of the swing, a little more uppercut with a lot of hand rotation and the follow-through is really short.

In 2019 his follow through is nearly horizontal and you even see the bat come back around him all the way back into the strike zone (behind him!) at nearly the same level the bat went through the strike zone on the initial swing. It’s much more a big circle like a discus thrower. I like that new swing!