You May Wish to Reconsider Nick Pivetta

In 2018, Nick Pivetta struck out 27.1% of the 694 batters he faced. That’s not as impressive a figure as it would have been 10 years ago, but it was still the 14th-best such figure in the game last year, and caused me to write a piece last November called “You May Wish to Consider Nick Pivetta” in which I implored you, the FanGraphs reader, to consider Nick Pivetta. It’s been eight months since that piece was published, and Pivetta has faced 295 more batters. It’s time to re-consider Nick Pivetta, and see whether his performance has rewarded your close scrutiny.

The reason I’m writing about this now is not because the answer to that question is yes — it is, in fact, emphatically no, in the sense that Pivetta’s performance this season has mostly been bad and has occasionally been awful — but because Pivetta strikes me as representative of a type. In particular, Pivetta strikes me as representative of a player who shows us just enough to dream on, just enough to see signs of a breakout, that we read into those signs and give them more credit than they perhaps deserve. Nick Pivetta strikes me as representative of our optimism as observers.

So let’s talk about Pivetta — what made us dream, and what’s happened to that dream as this 2019 season has worn on. (All stats are through July 13.) Pivetta’s stand-out pitch is his curveball, a massive breaker that spins (2872 rpm, fifth in the majors this year), dips (7.2 inches of horizontal movement, 14th), and dives (-9.7 inches of vertical movement, ninth) with the very best of its kind. That’s the pitch that Pivetta learned to use differently against righties and lefties in 2018, much to his credit, taking an offering that had been predictably in the bottom left corner of the zone regardless of count or opponent and putting it in on right-handers’ hands (even when behind in the count), and down and in to lefties. Here’s what that looked like:

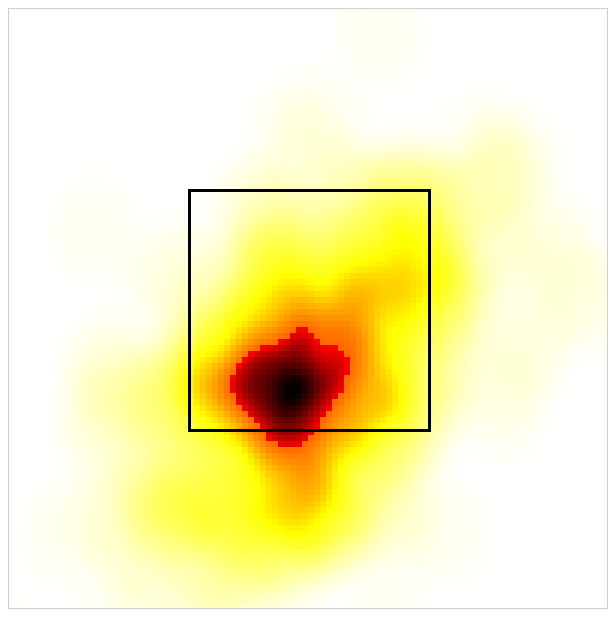

That differentiation helped give Pivetta his surprisingly high strikeout rate in 2018, and is what made me think that, with an improved defense behind him, Pivetta might be an anchor of the Philadelphia rotation in 2019. Well, 295 batters and 350 curveballs into his 2019 season, here’s what Pivetta’s curveball looks like now:

I won’t speculate about the ultimate cause of the change back to 2017’s shape that you see here here, not having spoken to the man, but I will say this: In 2018, right-handers facing Nick Pivetta had to contend with his big swinging hook up and in on their hands. This year, they don’t. And they’ve noticed: After posting a .308 wOBA against Pivetta in 2018, righties have beat up on him to the tune of a .385 this year even as lefties have made only modest gains, from .339 to .349.

That’s a worrying change, and it’s had predictable results. Pivetta’s curveball generated whiffs 12.0% of the time in 2017. That figure leapt to 15.8% in 2018 on the back of his improved command, and has dropped back down 12.3% of the time so far this year as the command has waned. His win values have described the same perfect mountain shape: -0.96 runs per 100 curveballs thrown in 2017, 1.15 in 2018, and -0.09 so far in 2019. Whatever was gained last year has been lost again, with downstream consequences for Pivetta’s overall performance.

The regression in the effectiveness of Pivetta’s curveball, particularly against right-handed hitters, has been magnified by his willingness to go to that pitch more often than ever before this year — perhaps a legacy of last year’s success. Each year since his debut has seen Pivetta’s fastball lose ground to his hook even as the two in combination continue to make up around four out of five of all pitches he’s thrown:

| FB% | CB% | FB+CB% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 65.9 | 14.8 | 80.7 |

| 2018 | 59.0 | 21.8 | 80.8 |

| 2019 | 51.5 | 31.5 | 83.0 |

That increase in curveballs would of course have been a good thing if the curveballs were anything near as effective this year as they were last. But they aren’t. Part of that decline is down to location, as Pivetta just hasn’t come up and in with the curveball to righties as often as he did before. But part of it, too, has been a concurrent decline in Pivetta’s fastball, which was already among the weaker such pitches in the game, and which has made in its slightness the curveball even weaker.

To wit: As Pivetta’s curveball has become more predictable he’s needed his fastball more than ever before, to set up the pitch by providing a point of comparison to batters now expecting to see at least one hook in any given sequence. That effort has been complicated by the unfortunate reality that, as Ben Clemens noted in May, Pivetta is among the league leaders in fastball velocity loss late in starts. His four-seamer clocks in about 1.2 miles per hour slower in the 51st-70th pitches of an appearance than it does in the first 50 pitches of a game. In consequence, the separation between Pivetta’s fastball and his curveball becomes much less pronounced late in games, and both pitches become increasingly easy to hit.

Ben interprets that fact pattern as suggesting that Pivetta might be a good multi-inning reliever, and there’s some merit too that argument. I’ll be a bit more cautious and suggest that it means he isn’t currently a particularly good starter. The Phillies apparently agree, because after slotting Pivetta into the rotation to start the year, they needed to see just four starts — four starts in which Pivetta allowed a .383/.435/.667 line to 93 opposing batters and posted a consequentially atrocious 8.35 ERA — to send the 26-year-old to Triple-A Lehigh Valley to work things out.

Something about Allentown had the desired effect, because Pivetta’s three starts back in the rotation were his best of the season. He notched five innings and three hits against the Cardinals on May 28 (not impressive until you consider his season-low in hits allowed to that point had been seven), and six scoreless innings against the Dodgers on June 2. And then, the crowning moment, a complete-game, one-run effort against the Reds at home on June 8. Those three starts alone, in which Pivetta did start to come up and in with a few curveballs against right-handed hitters — dropped his ERA from 8.35 to 4.93. But it was not to last. Pivetta allowed four runs to the Braves on eight hits his next time out, and he hasn’t had a better start since.

An aside, the decline in Pivetta’s performance this year stings deeply because of the dramatic improvement in the defense behind him. Last year, Philadelphia’s horrific fielding — a -146 team DRS that was the worst in the game by a substantial margin — contributed to the unusually large gap between Pivetta’s FIP (3.80) and his ERA (4.77). This year, happily, the Phillies’ defense is back up to an unspectacular but passable 4 DRS (the season, of course, has yet to fully play out), which has consequently narrowed the FIP-ERA gap substantially. If Pivetta just had last year’s FIP with this year’s defense behind him, he’d be contending for one of the 40 best marks in the game. But this year has brought regression and so that improved defense has remained, for Pivetta, an untapped advantage.

Coming into 2019, it was reasonable to look at Nick Pivetta’s 2018 and see in his 26-year-old arm and big swinging curveball an important part of a rotation expected to win 85 games and maybe the National League East. Reasonable, yes, but as it turns out incorrect, at least so far. Whatever magic we saw in Pivetta in 2018, whatever magic allowed us to dream on that arm and write stories about it, that hasn’t shown up again in 2019. That’s too bad for Pivetta, and too bad for the Phillies, and a good lesson for us. Every year, a certain number of young players will look like they’re ready to take the next step. A much smaller number of them actually will. Somewhere in between the dreams of November and the reconsiderations of July is the optimism of spring, and the first sounds of balls flying through air in Clearwater.

Rian Watt is a contributor to FanGraphs based in Seattle. His work has appeared at Vice, Baseball Prospectus, The Athletic, FiveThirtyEight, and some other places too. By day, he works with communities around the world to end homelessness.

Nice article Rian. I wonder if the curveball usage has increased as a result of his poor performance overall. Seems anecdotal, but perhaps he’s relying heavily on what he thinks is his best pitch because he’s found himself in tough spots more often.

Side note: I had the opportunity to play with Nick growing up in British Columbia. Hopefully he is able to turn a corner, but either way he’s making us proud!