A Splash of History: Looking Back on 20-Plus Years of McCovey Cove Homers

LaMonte Wade Jr. is having a wonderful season. As Michael Baumann wrote a few weeks ago, the step forward he’s taken in his swing decisions have fueled a career high 156 wRC+ and .429 OBP, both significant improvements from his 2021 breakout campaign. And while much of his development is the result of him reducing his swing rate, he’s still doing more damage on contact than his previous self. Last Friday, the man nicknamed “Late Night LaMonte” (due to his .975 career OPS in high leverage situations) inserted himself into the record books early in the evening, sending Dean Kremer’s first pitch of the game deep to right field for the 100th splash hit in Oracle Park history:

Since its opening in 2000, the right field wall has been one of the most distinctive features of Oracle Park. Despite measuring just 309 feet down the line (the second shortest of any big league park), it has been one of the most difficult to clear for a home run, with the wall’s 24-foot height and wind from the neighboring San Francisco Bay helping to suppress long balls. According to Statcast, Oracle Park is among the most difficult parks for left-handed hitters to hit homers despite grading out neutral overall. But on 100 occasions, hitters managed not just to clear the right field wall, but also to leave the stadium entirely.

While splash hits are cool and fun, it can be difficult to see the value in them from a site that values analytics in player and team evaluations. After all, the formula for wRC+ doesn’t add extra points if a home run ball touches the holy water of McCovey Cove. But splash hits, a type of hit invented in 2000 and that doesn’t count for any extra runs, can teach us a lot about how offenses are built in the modern game. Let’s start by looking at the most prolific splash hitters of the century:

| Name | Splash Hits | PA since 2000 | PA per Splash Hit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barry Bonds | 35 | 4072 | 116.3 |

| Brandon Belt | 10 | 5079 | 507.9 |

| Pablo Sandoval | 8 | 4342 | 542.7 |

| Denard Span | 5 | 1179 | 235.8 |

| Mike Yastrzemski | 5 | 1887 | 377.4 |

| LaMonte Wade Jr. | 5 | 852 | 170.4 |

| Brandon Crawford | 4 | 6037 | 1509.2 |

| Joc Pederson | 3 | 530 | 176.6 |

| Andres Torres | 2 | 1438 | 719 |

| Aubrey Huff | 2 | 1342 | 671 |

| Felipe Crespo | 2 | 228 | 114 |

| Michael Tucker | 2 | 833 | 416.5 |

| Ryan Klesko | 2 | 411 | 205.5 |

| A.J. Pierzynski | 1 | 510 | 510 |

| Alex Dickerson | 1 | 653 | 653 |

| Carlos Beltrán | 1 | 179 | 179 |

| Fred Lewis | 1 | 1048 | 1048 |

| J.T. Snow | 1 | 2692 | 2692 |

| Jason Vosler | 1 | 193 | 193 |

| John Bowker | 1 | 513 | 513 |

| José Cruz Jr. | 1 | 650 | 650 |

| Nate Schierholtz | 1 | 1316 | 1316 |

| Randy Winn | 1 | 2799 | 2799 |

| Scooter Gennett | 1 | 67 | 67 |

| Stephen Vogt | 1 | 280 | 280 |

| Steven Duggar | 1 | 805 | 805 |

| Travis Ishikawa | 1 | 752 | 752 |

| Tyler Colvin | 1 | 149 | 149 |

This list of players immediately illuminates a few trends. First, splash hits are one of the many facets of baseball that make it clear Barry Bonds was playing a different sport than everyone else. Despite being 35 years old when the park opened and drawing intentional walks about 10% of the time, he still managed to plop more than three times as many balls into the Bay as any other batter. (Fun fact: Since 2000, just one Giants hitter — Brandon Belt — has amassed even half as many homers as the 317 that Bonds hit in his final eight seasons of play.)

You don’t need me to tell you that Bonds was masterful at clubbing hard-hit fly balls (or really any kind of batted ball), but we have the numbers to back it up anyway. The batted ball tracking era began in 2002, encompassing most of his Oracle Park tenure. From then until his retirement, he ranked in the 72nd percentile in pull rate and the 99th percentile in fly ball rate. And while we didn’t have Statcast at the time, estimates of his exit velocities confirm his outlier status (as do his home run totals). He was basically a machine designed to feed souvenirs to sea creatures. But there are still 65 splash hits struck by players not named Bonds. Let’s see how others were able to rack up splash hits without the unlimited ability to crush balls at will.

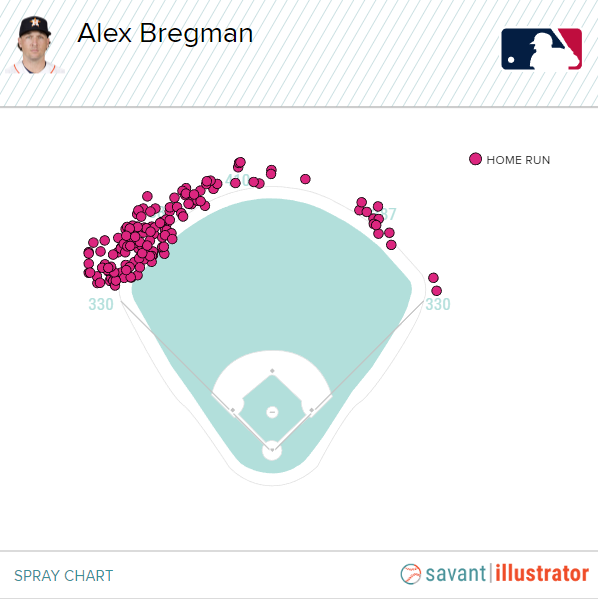

The key ingredient to splash hits has been emphasized far more in a more modern era of the game: pulling the ball in the air. While a more traditional philosophy of baseball instruction advocated for players spraying the ball to all fields, player development groups now teach power hitters to play to their strengths. In 2023, pulled fly balls have left the yard 37.2% of the time regardless of other factors like exit velocity, far more than any other type of batted ball. With the launch angle revolution, we’ve seen 40-homer seasons from players like Brian Dozier and Alex Bregman, whose raw power grades out as average at best. Stats like xwOBA and barrel rate aren’t huge fans of them either, but they outperform those metrics due to their ability to pull and elevate. Flies down the line don’t have to travel as far to leave the yard, increasing the likelihood of a homer even if the ball isn’t crushed.

Bregman is also a prime example of a hitter using beneficial park factors to his advantage, as the Crawford Boxes in Houston provide a perfect short porch for right-handed batters. In the Statcast era, he ranks second among all hitters in non-barreled homers, using his elite spray distribution to post consistently excellent power numbers.

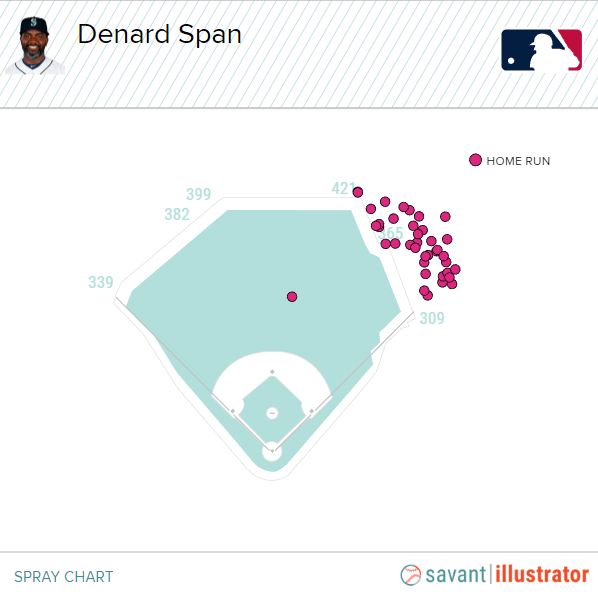

One potentially surprising name near the top of the leaderboard is Denard Span, who had five splash hits in a two-year stint with the Giants in 2016 and ’17. Despite spending his entire career as a hitter with average-at-best power, he was more than twice as effective at leaving the yard than thumpers like Belt and Pablo Sandoval. Span’s average exit velocity during that period was just 85.7 mph, the equivalent of 2023 Steven Kwan. Yet he still smacked a dozen homers because he could pull the ball down the line. Despite hitting the ball harder than just 8% of his peers, 14 of his 42 pulled fly balls left the yard during his Giants tenure. In 2016, among hitters with an average exit velocity of 86 mph or less, Span and fellow pulled fly ball enthusiast Stephen Vogt were the only ones to hit double-digit homers.

The pulled fly ball approach doesn’t just work for slap hitters like Span; it can turn batters who already have solid raw power into huge home run threats. Wade’s milestone splash hit was the fifth of his career, tying Span. But he’s not a speedy contact hitter who could make the most of the few flies he hit; he’s a true fly ball hitter with above-average pop. This season, he’s unlocked a new level of plate discipline, and with it a career high in xSLG by reducing the number of bad balls he puts in play. Similarly, Joc Pederson, another lefty who pulls the ball in the air frequently, has a .249 ISO over the past two seasons, putting him in the company of MVPs like Shohei Ohtani (.251) and Paul Goldschmidt (.247).

| Player | Fly Ball Rate | Max Exit Velocity | AB/HR |

|---|---|---|---|

| LaMonte Wade Jr. | 45% | 111.5 mph | 24.6 |

| Joc Pederson | 45% | 116.6 mph | 16.5 |

| League Average | 37.2% | 109 mph | 30.8 |

Beyond splash hits being emblematic of the launch angle revolution or indicative of previously undervalued skills, they tell the story of possibly the most decorated franchise of the new millennium. Most names near the top of the splash hit leaderboard are either Bonds or an everyday starter for their championship squads of the 2010s. Even rapidly ascendant names like Wade and Pederson are fixtures of a front office and coaching staff that has spearheaded league-wide trends in position player usage and development. And the exploits of the 2021 squad that came out of nowhere to win 107 games and lead the National League in wRC+ can be found in McCovey Cove; the eight splash hits from that year represent a post-Bonds single-season record.

More importantly, splash hits preserve the stories of the hitters who were never playoff heroes, All-Stars, or Silver Sluggers. Players don’t have to be a superstar or team leader; sometimes they can just be the backup infielder from a generation ago who made those lazy Tuesday nights in July a little bit more enjoyable. The guys who can make you reminisce with fellow fans, “Remember when Felipe Crespo, a utility player who hit 10 homers in his career, was the only hitter besides Bonds to have a splash hit for over three years?” Most longtime fans can spend hours recounting the walk-offs, web gems, or major league debuts of players who otherwise wouldn’t be remembered in the grand history of baseball. Through the splash hit, we are given a continuous chain of highlights and memorable moments that began when Bonds ruled the earth and will continue wherever trends in the sport take us next.

Kyle is a FanGraphs contributor who likes to write about unique players who aren't superstars. He likes multipositional catchers, dislikes fastballs, and wants to see the return of the 100-inning reliever. He's currently a college student studying math education, and wants to apply that experience to his writing by making sabermetrics more accessible to learn about. Previously, he's written for PitcherList using pitch data to bring analytical insight to pitcher GIFs and on his personal blog about the Angels.

I’d find this article more interesting if Splash Hits were counted for visiting players. I also still don’t think it’s fair that you have to play for the Giants to get credit for Splash Hits. For example, how many Splash Hits would Joc Pederson have if you counted all the ones he hit as a Dodger?

Yeah Jack Suwinski just had two in one game, iirc.

Certainly there is nothing in the article title or text that provides the true key ingredient to a splash hit. No, not pulling the ball in the air! The key ingredient is that you must play for the Giants. If the reader has to reason out the key ingredient on their own, that’s a writer fail. It would take one sentence to note that the article is using the team’s definition of a “splash hit” and therefore does not include visiting players.