The Awfully Quiet Pirates

Twitter can be an awfully contentious place. After noting NL Central payrolls in a tweet over the weekend, I received a barrage of replies and quote tweets loudly complaining about the Pirates’ failures to invest in the team. And it’s not just folks who are mad online causing a stir. Pirates fans have spoken with their wallets as well; attendance has dwindled since the team made three straight playoff appearances earlier this decade. The Pirates have a decent team, but have done almost nothing this offseason to improve it, and seem likely to enter 2019 with payroll at it’s lowest point in the last five seasons.

PNC Park opened in Pittsburgh in 2001, and despite a 100-loss team, nearly 2.5 million fans showed up to watch the Pirates play. The team averaged 93 losses and attendance of 1.75 million fans over the next 11 seasons. After topping two million fans in 2012 — as the club approached a .500 record for the first time since Barry Bonds left for San Francisco — Pittsburgh made the playoffs each year from 2013 to 2015 and averaged 2.4 million in attendance per season. The 2016 season was a losing one, and attendance waned as the summer wore on, but positive expectations kept it at a reasonably high 2.25 million fans. Expectations were lowered in 2017; attendance dropped below two million. After trading Andrew McCutchen and Gerrit Cole, confidence in the club among fans seemed to drop to a new low as attendance dipped below 1.5 million despite a winning record.

The Pirates actually put together a decent team a year ago, but losing their two stars meant that the club’s surprising start didn’t translate in to people at the gate. At the All-Star break, Pittsburgh was averaging just 18,155 fans per game. Contention and the acquisition of Chris Archer breathed some excitement into the franchise, and in the month after the All-Star Break, the team averaged 25,357 fans per game, a two-million-plus pace over the course of the season. But as the Pirates fell out of the race, attendance plummeted again.

Last June, Pirates President Frank Coonelly acknowledged that fans had lost some of their faith in the team, faith the team would need to earn it back.

“We are genuinely focused on those great Pirates fans who are coming out to PNC Park and how much we appreciate their support,” Pirates President Frank Coonelly said in a statement responding to a request for comment. “At the same time, we appreciate that we have work to do to bring back fans who are not joining us at the park this year. Our television ratings remain in the top five in MLB, so we know that Pirates fans are following the team. We understand that we need to provide a compelling reason for all of our fans to come to the best ballpark in baseball.”

It was perhaps with those sentiments in mind that Pittsburgh pursued Chris Archer and Keone Kela, players who might have helped them if they had continued to contend in 2018, but who also could improve the club in future seasons. Given that Archer’s contract, assuming the team picks up his option years, runs through 2021 — a timeline that coincides with that of their best player, Starling Marte — it would be reasonable to assume the Pirates see a window of contention during that stretch.

This is what the Pirates have done so far this offseason:

- Traded Jordan Luplow and Max Moroff to Cleveland for Erik Gonzalez, Dante Mendoza, and Tahnaj Thomas

- Signed Jung Ho Kang

- Signed Lonnie Chisenhall

- Signed Jordan Lyles

- Traded Ivan Nova for Yordi Rosario and international cap space.

- Claimed Aaron Slegers off waivers

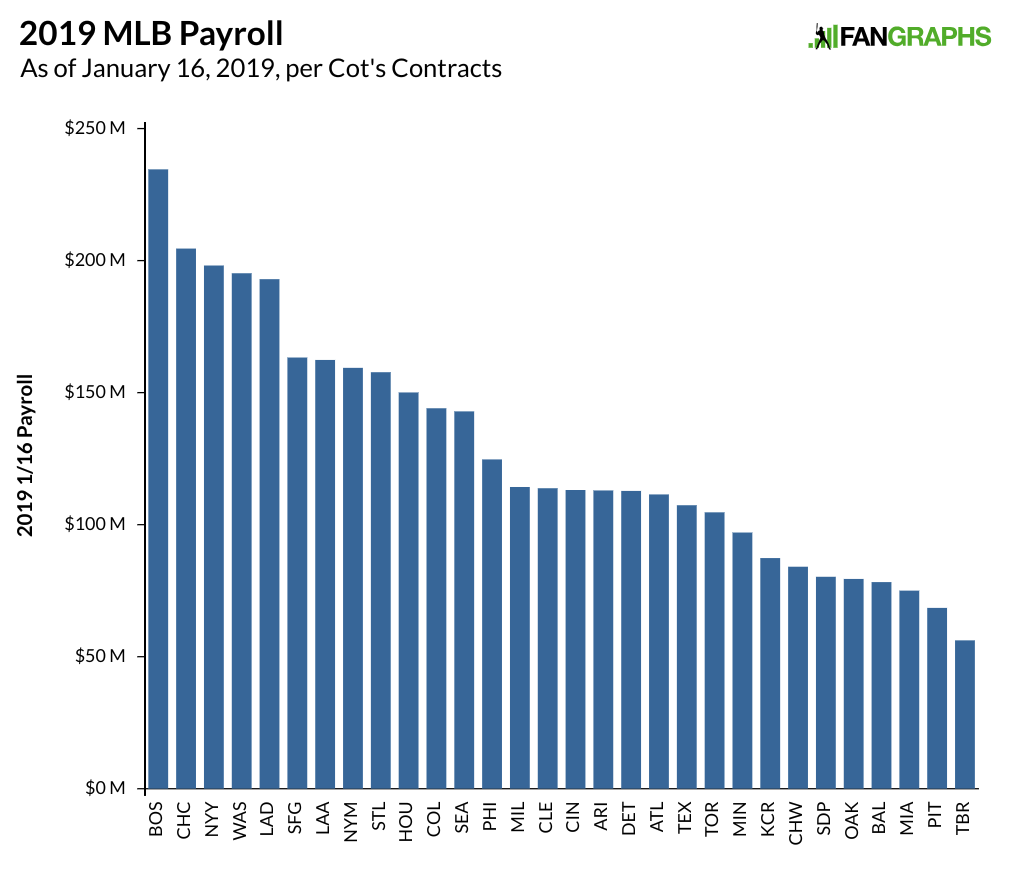

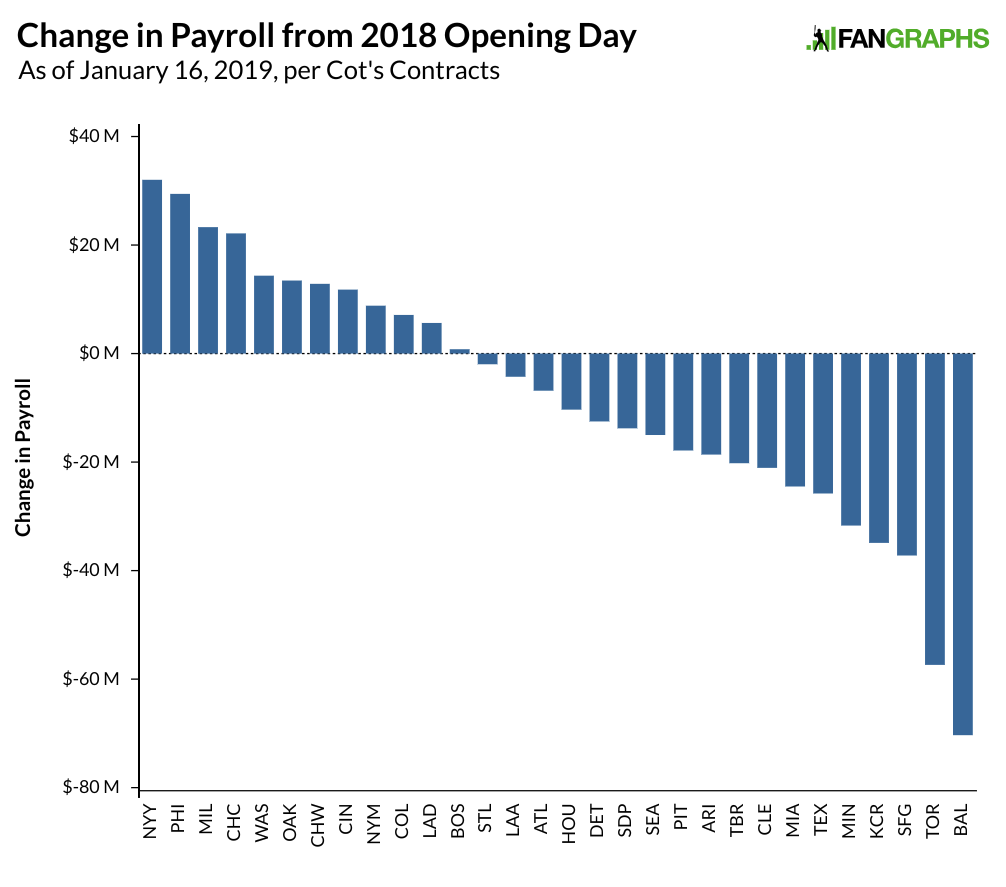

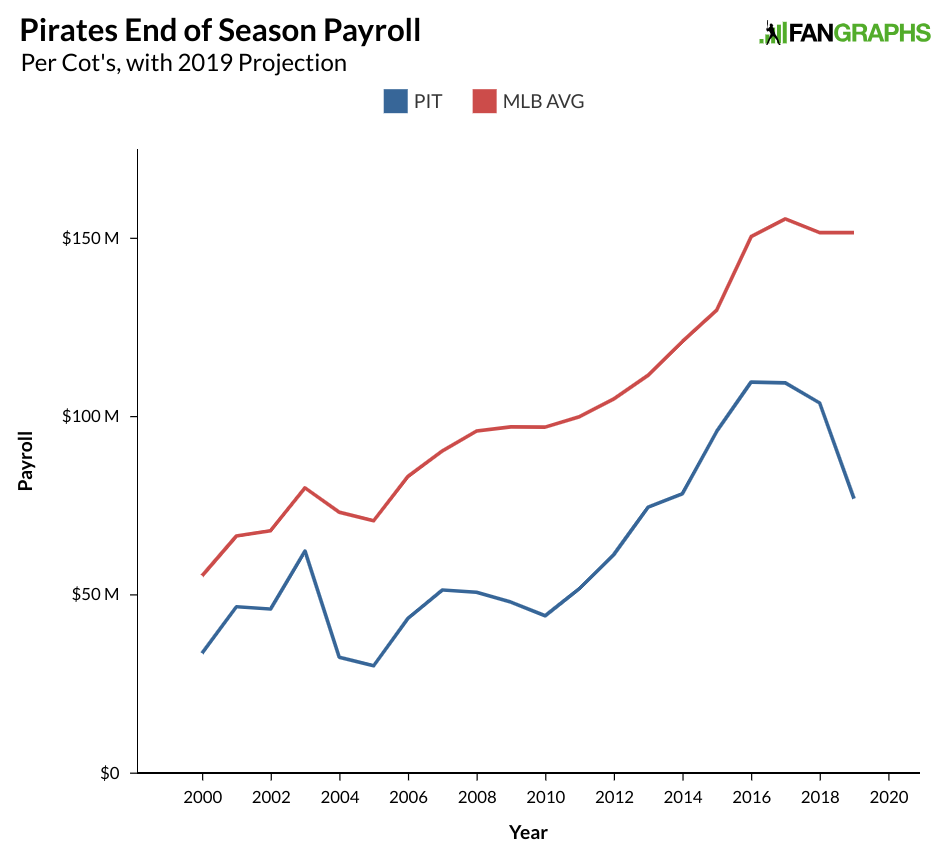

The team has also made the typical MLB teams minor league signings; among those, Tyler Lyons is the most interesting and promising. They also let Jordy Mercer go in free agency and declined Josh Harrison’s team option, though those weren’t big losses. The issue is the lack of progress on the major league roster from a team that, as Jeff Sullivan noted earlier this week, isn’t far from a playoff spot but currently has a projected Opening Day payroll of roughly $68 million. Only the Tampa Bay Rays have a lower projected payroll at the moment. This is how Pirates payroll has progressed over the years compared to MLB averages.

The first thing we might note is that the Pirates have always been a good bit below league average when it comes to spending. Given that the team plays in a smaller market, that’s not too surprising. The most obvious complaint for Pirates’ fans is the huge downturn in 2019 payroll we see as of now despite competing in 2018, losing no significant contributors this offseason, and gaining a full season of Chris Archer and Keone Kela. But that’s not where the angst regarding the Pirates’s spending really begins. If we were to look at graphs like the ones above for teams from similarly small markets like Milwaukee, Cleveland or Kansas City, we would expect to see similar graphs. What we would actually see, though, is that when those teams became competitive, they immediately invested more money into the roster to capitalize on that excitement, and ran close to (Cleveland) or above league-average payrolls (Milwaukee and Kansas City).

It’s that failure to invest that has disillusioned fans, and created a need for the team to somehow draw them back to the ballpark. Trading for Archer and Kela was a very good start, but at this point in the offseason, it’s hard to see how much more the Pirates can do given the remaining options and their purported budget constraints. They have mostly let the offseason pass them by, leaving deficiencies in the middle infield and in their rotation depth largely unaddressed.

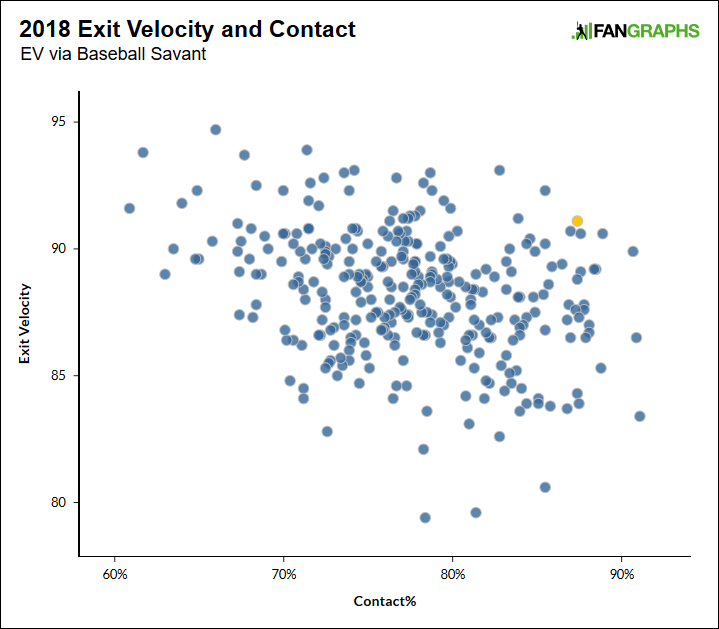

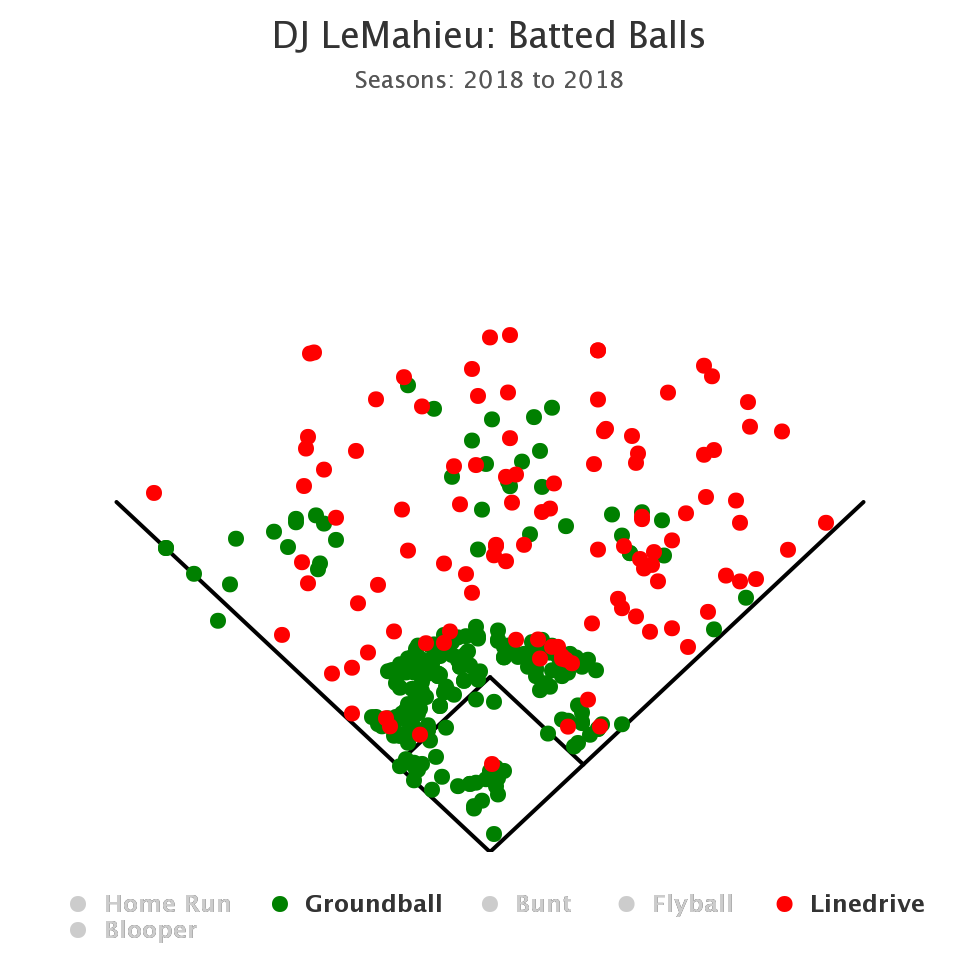

In the middle infield, the team has options like Adam Frazier, Kevin Newman, Kevin Kramer, and Erik Gonzalez, but in a free agent market with a glut of reasonably priced options at second base, it’s hard not to think an opportunity was missed.

In the rotation, Mitch Keller might be ready to take a spot, but further depth would have raised the floor — and potentially the ceiling — for a team still close to contention. There are still some starters out there who could help, like Wade Miley, Gio Gonzalez, and of course, Dallas Keuchel, but it is possible the Pirates missed the boat on a better fit earlier in the offseason.

The Pirates had an opportunity this offseason to continue repairing their relationship with their fans. But an approach that looked so promising at the trade deadline has left much to be desired this winter. In order to win back the fans — and potentially gain back close to a million attendees a season — the team will have to win consistently, or at least offer a reasonable expectation that they might. There are lots of teams with built-in buffers that help keep their attendance from falling too far. The Pirates are not one of those. Their quiet offseason isn’t likely to attract more fans to the park on Opening Day, and their lack of additions might also hurt them at the end of the season in the standings.