An Age-Adjacent Arm Angle Addendum

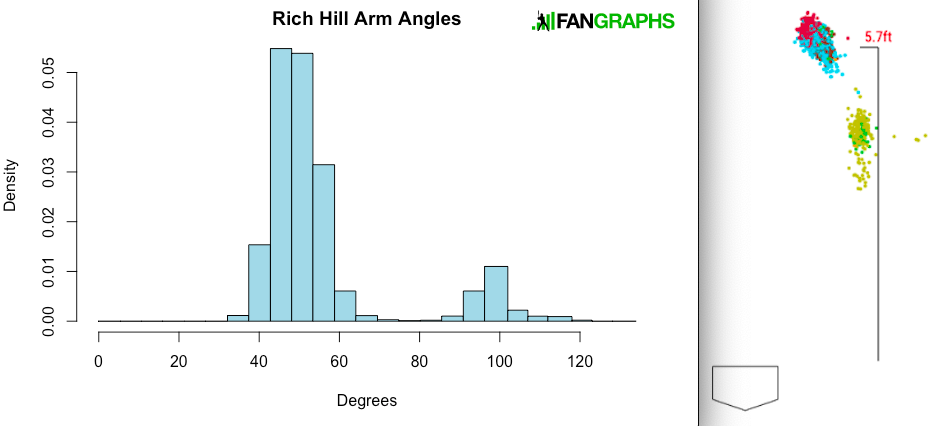

Last week, I wrote about arm angles, Nestor Cortes, and some appearance-based expectations hitters might have about a pitcher’s craftiness. During my data mining, I also noticed that Rich Hill popped up at or near the top of many arm angle rankings. Specifically, among the 473 hurlers who threw at least 500 pitches in 2022, Hill had the broadest range of arm angles and the second-highest arm angle standard deviation. Below are his release points in colorful dot form (via Baseball Savant) and his arm angle frequencies in histogram configuration:

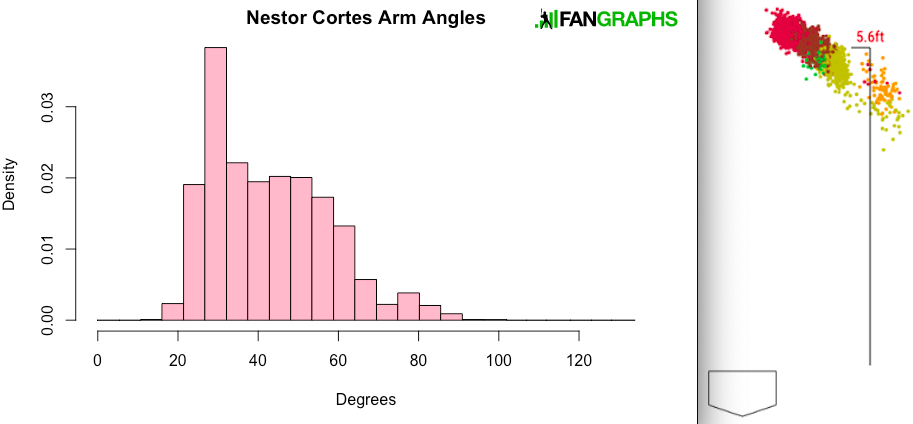

Hill typically comes at hitters from a three-quarters slot, though he does near a completely overhand slot at times. When he drops down, he provides his foes with anything from a sidearm to a fully submarine look. Cortes, for his part, placed second in range (just 0.4 degrees behind Hill) and fourth in standard deviation (2.5 degrees behind). But as you can see below, Cortes’ more significant drop-downs were not only less frequent than Hill’s but also closer to a more typical Cortes look. Whereas Hill has a very obvious gap between his drop-down and standard release, Cortes runs the gamut of angles between the two: