Election Season: Bonds and Clemens Lead the Contemporary Baseball Ballot

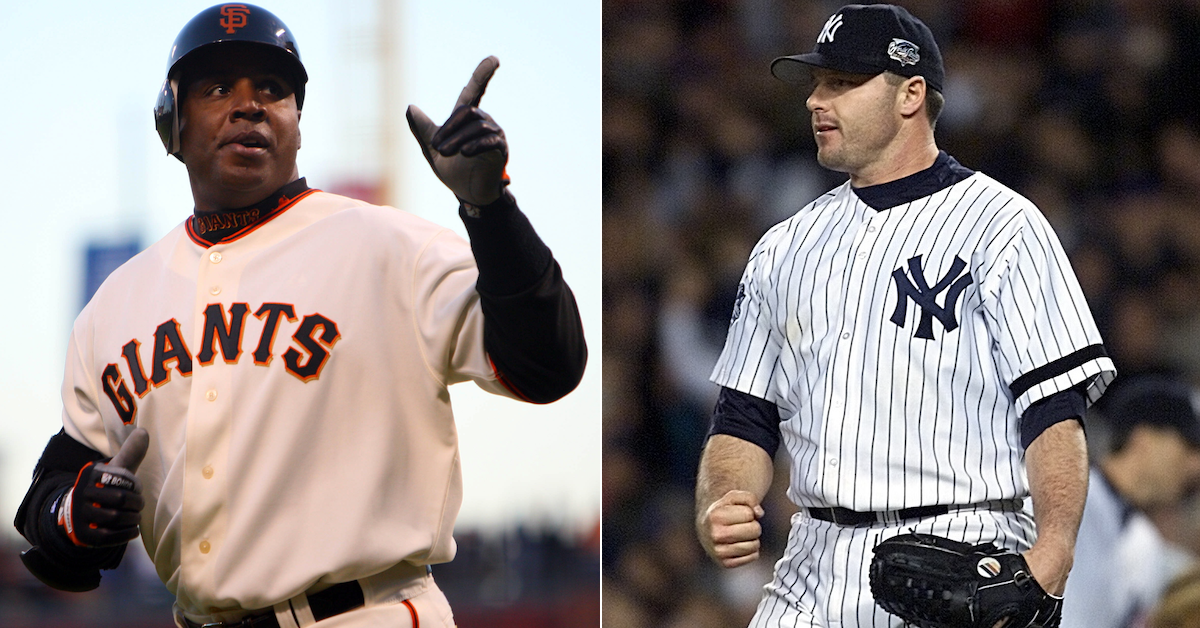

The champagne and tears have barely dried in the wake of this year’s instant-classic World Series, but election season is already upon us. On Monday, the National Baseball Hall of Fame officially unveiled the 2026 Contemporary Baseball Era Committee ballot, an eight-man slate covering players who made their greatest impact on the game from 1980 to the present and whose eligibility on the BBWAA ballot has lapsed. For the second year in a row, the Hall stole its own thunder, as an article in the Winter 2025 volume of its bimonthly Memories and Dreams magazine revealed the identities of the eight candidates prior to the official announcement. The mix includes some — but not all — of the controversial characters who have slipped off the writers’ ballot in recent years, including Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens, as well as a couple surprises. This cycle also marks the first application of a new rule that could shape future elections.

Assembled by the Historical Overview Committee, an 11-person group of senior BBWAA members, the ballot includes Bonds, Clemens, and fellow holdovers Don Mattingly and Dale Murphy, as well as newcomers Carlos Delgado, Jeff Kent, Gary Sheffield, and Fernando Valenzuela. As with any Hall election, this one requires 75% from the voters to gain entry. In this case, the panel — whose members won’t be revealed until much closer to election time — will consist of Hall of Famers, executives, and media members/historians, each of whom may tab up to three candidates when they meet on Sunday, December 7, at the Winter Meetings in Orlando. Anyone elected will be inducted alongside those elected by the BBWAA (whose own ballot will be released on November 17) on July 26, 2026 in Cooperstown. In the weeks before that, I’ll cover each candidate’s case in depth here at FanGraphs.

This is the fourth ballot since the Hall of Fame reconfigured its Era Committee system into a triennial format in April 2022, after a bumper crop of six honorees was elected by the Early Baseball and Golden Days Era Committees the previous December. The current format splits the pool of potential candidates into two timeframes: those who made their greatest impact on the game before 1980 (Classic Baseball Era), including Negro Leagues and pre-Negro Leagues Black players, and those who made their greatest impact from 1980 to the present day (Contemporary Baseball Era). The Contemporary group is further split into two ballots, one for players whose eligibility on BBWAA ballots has lapsed (Fred McGriff was elected in December 2022), and one for managers, executives, and umpires (Jim Leyland was elected in December 2023). Non-players from the Classic timeframe are lumped in with players, which doesn’t guarantee representation on the final ballot.

The 2022 reconfiguration also trimmed the number of candidates per cycle from 10 to eight, making every Era Committee ballot that much more notable for its omissions as well as its inclusions. Particularly with this year’s rule change, this will be something for Hall monitors to get used to. Under the new rule, starting with this cycle, candidates who don’t receive at least five out of 16 possible votes will be ineligible to appear on the next ballot three years later, when that pool of candidates is considered again. Those who don’t receive at least five of 16 votes on multiple Era Committee ballots will no longer be eligible for future consideration, period.

As I noted in March, the first part of that change is a reasonable response to a massive backlog of candidates who generally come from three pools: those who got short shrift in the years before voters began incorporating advanced statistics such as OPS+, ERA+, WAR, and JAWS into their deliberations; those who were linked to performance-enhancing drug usage and lingered on the ballot despite statistics and accomplishments that would have guaranteed them swift elections without that baggage; and those who were overshadowed on the ballot by PED-linked candidates, sometimes to the point of falling off after a single appearance due to the Five Percent Rule.

In theory, the rule change could allow for a larger group of candidates to get a shot at election. However, the second part of that change — permanent ineligibility — is unnecessarily heavy-handed, and not only because it can punish a candidate merely for landing on a ballot at the wrong time. As first documented by Bill James in The Politics of Glory (1994) and then explored in my own book, The Cooperstown Casebook (2017) and my subsequent coverage, the makeup of a committee’s membership can skew the voting results and give off the appearance of favoritism or cronyism. Particularly in recent years, the Hall has amply demonstrated its influence on outcomes. Sometimes it stocks a committee with multiple former teammates, managers and executives likely to support a favored candidate (the recent elections of Harold Baines and Dave Parker come to mind), and sometimes it stacks the deck with familiar antagonists. Former players union chief Marvin Miller was stymied for decades by committees chockfull of executives who were on the management side during the Reserve Clause era or during baseball’s late-1980s collusion scandal; he wasn’t elected until the 2020 Modern Baseball Era Committee ballot — against his own wishes — about seven years after his death.

Three years ago, the Hall selected Jack Morris, Ryne Sandberg, and Frank Thomas — three of the era’s most outspoken players on the subject of PEDs — for the committee. It was impossible not to read their participation as a purpose pitch designed to knock the candidacies of Bonds and Clemens down, and that’s exactly what happened. The pair received fewer than four votes apiece (as did two other candidates, Albert Belle and the PED-linked Rafael Palmeiro); by custom, the actual totals below a certain threshold aren’t publicly revealed. The prospect of a similarly engineered committee that could punt Bonds and Clemens into oblivion after a similar result this time around looms large. That would be an outrage given that each received over 50% of the vote from the writers six times and over 60% of the vote three times, as there’s simply no precedent for permanently excluding such widely supported and otherwise eligible candidates from consideration.

Below is a sortable table of 28 candidates that includes every player actually on this ballot; every player from the 2017–23 Era Committee ballots who is still eligible for this period; a handful of starting pitchers from the Contemporary period with reasonably solid cases based on S-JAWS, particularly given the dearth of starting pitchers elected from the past 50 years; and a handful of other candidates with a JAWS of at least 50. The default sorting used for the table is the Hall of Fame Monitor score, where 100 indicates “a good possibility” and 130 “a virtual cinch.”

| Player | Pos. | HOFM | JAWS | J+ | Rk | BW% | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barry Bonds | LF | 340 | 117.8 | 64.3 | 1 | 66.0% | < 25% | ||||

| Roger Clemens | SP | 332 | 101.6 | 44.8 | 3 | 65.2% | < 25% | ||||

| Sammy Sosa | RF | 202 | 51.2 | -4.8 | 20 | 18.5% | |||||

| Rafael Palmeiro | 1B | 178 | 55.4 | 1.9 | 12 | 12.6% | < 25% | ||||

| Curt Schilling | SP | 171 | 63.5 | 6.7 | 23 | 71.1% | 43.8% | ||||

| Mark McGwire | 1B | 170 | 52.0 | -1.5 | 18 | 23.7% | ≤31.3% | ||||

| Gary Sheffield | RF | 158 | 49.3 | -6.7 | 25 | 63.9% | |||||

| Albert Belle | LF | 135 | 38.1 | -15.4 | 42 | 7.7% | ≤31.3% | ≤31.3% | < 25% | ||

| Don Mattingly | 1B | 134 | 39.1 | -14.4 | 39 | 28.2% | <43.8% | ≤18.8% | 50% | ||

| Jeff Kent | 2B | 123 | 45.6 | -11.4 | 22 | 46.5% | |||||

| Dale Murphy | CF | 116 | 43.9 | -14.1 | 27 | 23.2% | <43.8% | ≤18.8% | 37.5% | ||

| Carlos Delgado | 1B | 110 | 39.4 | -14.1 | 38 | 3.8% | |||||

| David Cone | SP | 103 | 52.8 | -4.0 | 48 | 3.9% | |||||

| Lou Whitaker | 2B | 93 | 56.5 | -0.5 | 13 | 2.9% | 37.5% | ||||

| Kevin Brown | SP | 93 | 56.2 | -0.6 | 33 | 2.1% | |||||

| Willie Randolph | 2B | 92 | 51.1 | -5.9 | 16 | 1.1% | |||||

| Kenny Lofton | CF | 91 | 55.9 | -2.1 | 10 | 3.2% | |||||

| Orel Hershiser | SP | 91 | 47.5 | -9.3 | 77 | 23.7% | ≤31.3% | ≤31.3% | |||

| Joe Carter | RF | 87 | 20.5 | -36.2 | 121 | 3.8% | ≤31.3% | ≤31.3% | |||

| Keith Hernandez | 1B | 86 | 50.8 | -2.7 | 22 | 10.8% | |||||

| Will Clark | 1B | 84 | 46.3 | -7.2 | 28 | 4.4% | ≤31.3% | ≤31.3% | |||

| Bret Saberhagen | SP | 71 | 50.6 | -6.2 | 57 | 1.3% | |||||

| Dwight Evans | RF | 70 | 52.3 | -3.7 | 17 | 10.4% | 50% | ||||

| John Olerud | 1B | 68 | 48.6 | -4.9 | 25 | 0.7% | |||||

| Buddy Bell | 3B | 67 | 53.4 | -2.7 | 15 | 1.7% | |||||

| F. Valenzuela | SP | 67 | 36.6 | -20.2 | 173 | 6.2% | |||||

| Dave Stieb | SP | 56 | 49.1 | -7.7 | 63 | 1.4% | |||||

| Rick Reuschel | SP | 49 | 56.4 | -0.4 | 32 | 0.4% |

Based on their HOFM scores, this ballot includes only seven of the top 12 candidates from the pool, where three years ago, eight out of the top 11 made the cut. The new slate is even weaker by JAWS — or rather J+, the margin between a player’s JAWS and the standard at his position – as just three out of the top 21 from this pool made the ballot, compared to four of the top 20 last time. Sort the table by either JAWS or J+ and you can see how few opportunities for election those below Bonds and Clemens have received from the Era Committee process. That’s not progress, to say the least.

Bonds, the all-time home run leader and a seven-time MVP, and Clemens, a 300-game winner and seven-time Cy Young winner, are by far the most statistically qualified candidates by any of the aforementioned measures, as well as the two who came closest to election by the writers. Their PED connections date to the era before Major League Baseball and the players’ union put a testing-and-penalty program in place, but while they began trending toward election after former commissioner Bud Selig — who oversaw the game’s belated response to the influx of steroids — was elected in 2017, Hall vice chairman Joe Morgan openly lobbied voters not to elect any PED-linked candidates, thwarting their progress.

Mattingly and Murphy are a pair of former MVPs (the latter a two-time MVP) and multiple Gold Glove winners whose careers were curtailed by injuries. Both project the kind of wholesome, scandal-free image that the Hall would love to harness. Along with the perception of their traditional accomplishments (as summarized by the HOFM scores), that helps to explain why they keep getting chances despite meager support from voters prior to 2023, not to mention their flimsy cases on the advanced statistical front.

Among the first-timers, Kent and Sheffield aged off the BBWAA ballot since the last time around. Kent played with Bonds on the Giants from 1997–2002, and won an MVP in 2000, but the clubhouse was hardly big enough for the two of them. Though he set the record for most home runs by a second baseman (351 out of 377 for his career), modest on-base percentages and subpar defensive metrics yielded a case that remains unremarkable from an advanced stat POV. Between that, the ever-present crowd on the ballot, and prickly behavior toward the media — which, to be fair, often wanted him to talk about Bonds — he didn’t reach 20% until 2020, his seventh year on the ballot, but rallied to 46.5% in his 10th year. Given his PED-free reputation, he might be this ballot’s best bet for election.

Sheffield, who clubbed 509 career home runs, was one of the heaviest hitters and most misunderstood players of his time, dating back to the way he was mishandled by the Brewers at the outset of his career. Controversies — many of which involved his contract situation — followed wherever he went. Most notably, he was linked to the BALCO scandal due to his connection to Bonds, with whom he briefly trained, but by all accounts their relationship crumbled before Sheffield could wind up in deeper water. Even with defensive metrics so dreadful they seem hyperbolic, his advanced statistical case is stronger than Kent’s, and he fared better among the writers. While he didn’t break 15% during his first five years on the ballot, his 10th-year share (63.9%) is higher than any other PED-linked player besides Bonds and Clemens.

Of the two other newcomers, Valenzuela and Delgado, neither lasted long on the writers’ ballot, so their presence here could be read as a positive sign… if there weren’t already stronger candidates in a similar position. After a brief cup of coffee as a 19-year-old in 1980, Valenzuela burst upon the scene in the strike-shortened ’81 season, winning the NL Rookie of the Year and Cy Young awards while helping the Dodgers to their first championship in 16 years. More than that, he became a cultural phenomenon, as Fernandomania transformed baseball’s landscape by drawing droves of Latin American fans to the game, which particularly resonated in a Los Angeles still healing from the wounds caused by the eviction of nearly 2,000 Mexican American families to construct Dodger Stadium. While he had a few other great seasons for the Dodgers after 1981, his arm was overtaxed; the last decade of his career was largely a grind due to injuries, and he slipped off the BBWAA ballot after just two tries. After his career, he moved up to the Dodgers’ Spanish-language broadcast booth, and was still working in that capacity until he died in October 2024, just shy of his 64th birthday. I’m on record as believing that Valenzuela’s hybrid career as a player, broadcaster, and global ambassador is better recognized in the context of the Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award, which was created in 2008. For as iconic as he is — to say nothing of the fact that he’s a personal favorite — he feels out of place here.

Delgado made just two All-Star teams during his career but clubbed 473 homers, the third-highest total of any non-PED-linked player outside the Hall behind Albert Pujols and Miguel Cabrera, neither of whom is yet eligible for election. Delgado was the conscientious slugger. In an age when most athletes shirk political stances for fear of narrowing their appeal, he was unafraid to protest against the war in Iraq, publicly opposed the United States Navy using part of his native Puerto Rico for bombing practice, and refused to go through the motions during the post-9/11 ritual of “God Bless America” at Yankee Stadium and elsewhere. He was lost in the shuffle on the 2015 ballot, receiving less than 5%, but wasn’t eligible for this process until his 10-year window would have run out. He’s probably got zero shot at election, but his story deserves to be retold.

On the subject of players who went one-and done, Johan Santana won’t be eligible until the 2029 Contemporary ballot, barring another reconfiguration of the process. Even given the appeal of those candidates — particularly on the advanced statistical front – nobody should be holding their breaths, because the history of one-and-dones who landed on Era Committee ballots is a short one. Ted Simmons made three such ballots before finally being elected on the 2020 Modern Baseball ballot, but Whitaker, who received 37.5% that same year, has yet to return. Carter and Clark, in a similar boat to Delgado, both sank without a trace on BBWAA ballots but got a couple of looks on Today’s Game ballots due to a shallower pool of candidates. In that light, the glass-half-full view of Delgado’s inclusion is that it bodes well for similarly ignored candidates in the future. The glass-half-empty view is that there are stronger Contemporary candidates from the one-and-done pool who have never gotten another look, though some such as Brown (who wound up in the Mitchell Report) and Lofton (who allegedly sent sexually explicit photos of his body to a female employee) have issues that may dim the enthusiasm of the Hall (and the HOC) to put them up for election.

To these eyes, it would have been better to see Whitaker, whose JAWS case is stronger than any of the other one-and-dones, get another shot before Delgado or any of the aforementioned. Likewise when it comes to Evans, who lasted just three years on the ballot but fared even better than Whitaker in 2020 (50%) and looks much stronger in JAWS than candidates who lingered on the ballot for 15 years, such as Mattingly and Murphy.

It’s not hard to understand why McGwire, Palmeiro, and Sosa aren’t here, while the omission of Schilling — who repeatedly sabotaged his candidacy in unprecedented fashion (I kept all the receipts) and even tried to get himself dropped from the 2022 BBWAA ballot after several voters publicly indicated a desire to rescind their ’21 votes based on his support for the January 6 insurrection attempt by supporters of Donald Trump — is a welcome respite. So we’ve got that going for us, which is nice, though Schilling’s solid showing on the 2023 ballot suggests he could be included next time if other candidates fall victim to the new threshold rule.

A guy could write a book about the omissions. Even so, the eight candidates we do have, along with the upcoming candidates on the writers’ ballot, will command enough attention over the next several weeks to keep us plenty busy. Stay tuned.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

Mattingly gets his 50th shot, I love Fernando, but, he’s really not a HOF caliber as a player, meanwhile no Whitaker.

BOO!!!!!

Yeah, Whitaker should be a slam dunk hofer imo.

Why? When you rank the best seasons of second basemen by fWAR over the last fifty years, Whitaker’s best was only fifty-first. He only had three seasons of 5+ fWAR. He only received MVP votes one season of his career.

Sweet Lou was a very good baseball player for a very long time, but I don’t think reaching a cumulative WAR threshold is enough for inclusion. Slam dunk Hall of Famers should be the absolute best players of their generation and Whitaker was a tier or two below that.

Whitaker is 13th all time in second baseman JAWS and .5 WAR away from matching the average JAWS score for the top 20 HoFers at 2B.

That’s a small Hall you’re looking at.

Edit: .5 JAWS score away, not WAR

Again, a cumulative WAR threshold isn’t enough for me. His peak just wasn’t high enough. I remember that era, and Whitaker was never thought of as one of baseball’s elite players, much less a Hall of Famer. He was known for being what WAR shows him to be, a consistently productive player.

Please reread what I wrote.

Please reread what I wrote. You literally didn’t address any of the points that I made.

It was an attempt for you to understand my reply. Then you failed to understand my attempt for you to understand my reply. Then you got pedantic.

So, not worth my time.

And I am attempting for you to understand that JAWS is based on WAR. Then you failed to understand my attempt for you to understand my reply. Then you started using insults.

So, yeah, definitely not worth your time.

I don’t attempt debate when I realize the other side is living on Mars.

JAWS accounts significantly for peak value; it is 50% career WAR and 50% 7-best-years peak WAR. It is not merely that Whitaker accumulated his way to a viable JAWS score; he compares favorably with many other HoF 2B, which is not a position that has a bunch of Babe Ruths with 10+ win seasons in its positional average.

One of the main causes of Whitaker’s candidacy is that 2B are under-represented in the Hall of Fame, as 3B are as well (though 3B even moreso). HoF voters have long expected lower offensive contributions from shortstops and catchers, but held 2B and 3B to similar offensive standards as corner OFs and 1Bs.

Its true that Whitaker doesn’t have one of the best 7-year peaks at his position, but it’s still better than NINE enshrined 2B, many of whom are much, much worse. Not only that, but 6 of the 8 players with better 7 year peaks than Whitaker started their careers after his was over – they are modern players. At the time of his retirement, he had the 2nd-best 7 year peak of 2B not inducted into the HOF, trailing only Bobby Grich.

There is one player from his generation who is clearly ahead of him and that guy is enshrined (Sandberg). The simple truth is that the 3 best second-basemen to start their careers in the 1970s were Sandberg, then Grich and Whitaker in some order, and somehow 2 of those guys aren’t in the Hall.

Given how thin the position is – and the fact that it includes a lot of guys who have no statistical case for entry and are there for other reasons (like Mazeroski and Miller Huggins), the reality is that Whitaker (and Grich) belong in in the Hall of Fame unless you are one of the tiniest-Hall people imaginable.

If you use fWAR, Whitaker’s seven year peak (35.6) is better than six Hall of Fame second basemen: Tony Lazzeri (34.5), Nellie Fox (34.5), Johnny Evers (33.8), Bid McPhee (33.8), Red Schoendienst (28.1), and Bill Mazeroski (21.8).

He’s behind Roger Hornsby (75.6), Eddie Collins (62.7), Joe Morgan (58.5), Nap Lajoie (58.0), Charlie Gehringer (49.4), Jackie Robinson (48.2), Joe Gordon (47.9), Frankie Frisch (47.0), Rod Carew (44.4), Ryne Sandberg (43.9), Craig Biggio (40.8), Roberto Alomar (40.2), Bobby Doerr (37.7), and Billy Herman (36.1).

I agree that Whitaker is more deserving than some of the other second basemen already enshrined, but that isn’t a good argument, otherwise Harold Baines would get in a whole host of players. I also don’t agree that the Hall needs to induct a certain number of second basemen. The point of positional adjustments is to compare players from different positions. Narrowing down to “second-basemen to start their careers in the 1970s” also isn’t relevant to the Hall of Fame, as that’s cherry picking endpoints. The Hall of Fame is about how a player compares to the best in the entire history of the sport.

Whitaker wasn’t just very good for a very long time. That short sells just how remarkable his ability was to sustain being very good for such a long time.

For all players (regardless of position) with at least 9900 PAs, Lou is t-58th in wRC+ at 118.

But he was playing 2B, a position that demands proficient defensive skill.

Historical defensive metrics are obviously tricky, but Whitaker didn’t just play 2B, a position that demands proficient defensive skill, he played it exceedingly well.

There have only been 63 players all-time with at least 9900 PAs and a wRC+ as high as Lou’s 118 and Lou is, let’s see… fifth all-time in defensive value!

Name PA/wRC+/Def

He did not have the peak seasons, but putting up a 118 wRC+ over 9900 PAs and excellent defense at 2B is just as commendable, if a different model of excellence. In some respects, “posting up” for 9900 PAs and still putting up these numbers is the definition of a Hall of Fame baseball player

I know Mr. Jaffe captures this dichotomy between peak and sustained excellence with the JAWS system but it’s still impressive to see Lou’s credentials laid out.

Whitaker wasn’t just very good for a very long time. That short sells just how remarkable his ability was to sustain being very good for such a long time.

For all players (regardless of position) with at least 9900 PAs, Lou is t-58th in wRC+ at 118.

But he was playing 2B, a position that demands proficient defensive skill.

Historical defensive metrics are obviously tricky, but Whitaker didn’t just play 2B, a position that demands proficient defensive skill, he played it exceedingly well.

There have only been 63 players all-time with at least 9900 PAs and a wRC+ as high as Lou’s 118 and Lou is, let’s see… fifth all-time in defensive value!

Name PA/wRC+/Def

George Davis 10151/118/230.9

Honus Wagner 11739/147/184.4

Willie Mays 12541/154/169.6

Mike Schmidt 10062/147/150.7

Lou Whitaker 9967/118/127.1

He did not have the peak seasons, but putting up a 118 wRC+ over 9900 PAs and excellent defense at 2B is just as commendable, if a different model of excellence. In some respects, “posting up” for 9900 PAs and still putting up these numbers is the definition of a Hall of Fame baseball player

I know Mr. Jaffe captures this dichotomy between peak and sustained excellence with the JAWS system but it’s still impressive to see Lou’s credentials laid out.

It takes more than 1B, but less than SS or 3B.

No, he didn’t. Whitaker wasn’t even close to someone like Frank White defensively at second.

Whitaker never provided excellent defense. He was a good fielder and a very good hitter for his position. White was an excellent fielder and poor hitter for his position.

No, the definition of a Hall of Fame baseball player is someone who was famously great at playing baseball. Everyone thought Whitaker was very good and wished that their team had someone like him, but in that era, no one feared him. He wasn’t considered to be elite, which is why he only garnered MVP votes in one season of his career.

Ugh. I feel dumber for reading this.

Insults are not a compelling rebuttal.

Based on your reply above, you don’t appear capable of coherent discourse.

This would read more like an explanation than an excuse if you had even attempted to respond to a single one of my points, much less succeeded at doing so.

Instead, it looks like someone attempting to run from an argument after they realized that they didn’t have any intelligent points to make, but still wanting to pretend that they “won.”

You’re, like, 0/10 on analysis so far, they might want to send you to the minors.

I mean…you opened with an empirically false statement, closed with an appeal to vote for Jim Rice, and everything between was just as bad.

That’s the second comment on this article where you used empirical incorrectly. I recommend that you look up what the word means.

I opened by saying: “When you rank the best seasons of second basemen by fWAR over the last fifty years, Whitaker’s best was only fifty-first. He only had three seasons of 5+ fWAR. He only received MVP votes one season of his career.“

Each of those statements are factual.

Never once in my entire life have I advocated for Jim Rice to make the Hall of Fame. His seven year peak is barely above Whitaker’s. Please don’t lie just because you wish I was wrong and can’t argue against the things I actually said.

Bud, you follow me around FanGraphs articles disagreeing with everything I say because you’re irrationally angry over the times that I have previously proven you wrong. You evaluating the veracity of my comments is like asking a Red Sox fan to evaluate the Yankees.

Oh, honey:

You’re literally a Twitter reply guy…right to the point of celebrating the fact that people eventually ignore your desperate screams of “DEBATE ME, BRO!!!!!!!!!”

Your trick is being so incoherent that we genuinely can’t tell whether you’re dumb or trolling.

You responded to me by falsely claiming that I “opened with an empirically false statement” when every part of my original comment was factually correct, and you blatantly lied by claiming that I made “an appeal to vote for Jim Rice.“

I have never wanted to debate you. I would have to value your opinion for that. I correct false statements that you make.

Again, this bluster would be more compelling if you weren’t so angry over the previous times I proved you wrong that you obsessively follow me around comments sections looking to start up another argument.

Just because a position player isn’t feared much on offense, relatively speaking, doesn’t necessarily mean he’s not a Hall of Fame caliber player, or guys like Ozzie Smith never would’ve made it in.

Offhand I don’t know how good Whitaker was at defense, but if he was an excellent defender, that combined with his offense could still make for an elite player during his peak, which doesn’t always show up in MVP voting.

If nothing else, 2B is still higher on the defensive spectrum than 3B.

Fear doesn’t just come at the plate. Teams didn’t want to hit balls to shortstop against the Cardinals precisely because Ozzie was such a wizard.

Like I said, Whitaker was considered a good defender but not even close to Frank White. And as for MVP voting, Whitaker’s teammate Alan Trammell received votes in seven seasons despite Whitaker being a slightly better hitter.

No, third base is higher on the spectrum than second base due to having less reaction time to handle balls in play and having to make more difficult throws. Brandon Lowe has played a variety of positions badly for the Rays, but they never even tried him at third. Or look at Jazz Chisholm, who the Yankees tried at third before moving him back to second.

If Lou Whitaker wasn’t in the same league as Frank White, why did he win 3 GG from 1983-1985? White was still in his prime & while White did win the 5 before that & also in 1986-87, the fact Whitaker won any says something about how his defense was viewed.

DRS & Total Zone both have him #9 ALL TIME. So he clearly WAS a great fielder from the metrics we have, he just happened to play at the same time with 3 other great fielders (White, Randolph, Grich..who he ranks ahead of in both, BTW).

I also don’t think 3B is above 2B on the defensive spectrum…especially in the 80’s when strikeouts were so much lower & launch angle wasn’t a thing yet.

Add it up & you have a great fielder at a key defensive position, who was a above average hitter at a position where that is a huge bonus. also a good baserunner.

Whitaker won in those seasons for the same reason that Derek Jeter won five gold gloves, because his team was very good during that stretch. According to Total Zone rating, Whitaker was the 10th, 11th, and 19th best second baseman during those three Gold Glove winning seasons.

Yes, because Whitaker played 19069.0 innings at second base, the third most all-time. But his career Total Zone rating is just 77, far behind Frank White at 125 or Willie Randolph at 115 or Bill Mazerowski at 148.

No, he wasn’t. If you look at Total Zone by inning played at second base, White was at 0.00702. Randolph was at 0.00616. Grich was 0.00468. Whitaker was 0.00404. And again, I am old enough to remember those days. Whitaker was absolutely not viewed as a great fielder, he was viewed as a good one.

Why would launch angle affect infield defense? It’s a fact that balls get hit much harder on average to third than second and always have. It’s a fact that throws from third require much more distance than throws from second and always have, which is why second basemen have the luxury of sitting significantly deeper than third basemen, because they have more time to make whatever throw comes after fielding the ball.

Unlike FG, B-Ref bases its positional adjustments on an empirical standard.

Over Whitaker’s career, 2B was +5 and 3B was +2.

That doesn’t fit into yer man’s narrative though, so I fully expect the data to be summarily ignored…with a deluge of whataboutism to follow.

Neither part of that is true. BREF doesn’t use an empirical standard, nor is it unlike FanGraphs. Both sites assign rounded thresholds for positional adjustments based on comparisons, they just use different metrics. My understanding is that FanGraphs uses figures from Tangotiger, who got there by looking at UZR.

BREF is different in that it looks at offensive performance at the position. Their Positional Adjustment section says the following: “If you take a quick look at the batting performance by defensive position, you’ll quickly see that teams are willing to sacrifice offense at “defensive” positions (stats are prorated to 650 plate appearances).” So, the worse the hitters are at a position, BREF assumes that teams are placing more value on defense at that position.

That’s why you get weird things like BREF going from +3.00 for second basemen in 1874 to +2.50 for second basemen in 1875.

BREF had second basemen at +4.00 from 1975 through 1988, then +3.50 in 1989, and +3.00 from 1990 through Whitaker’s final season in 1995.

FanGraphs uses a static version based on calculations made 19 years ago, based on four years of data from the 2002-2005 model of UZR.

Significantly, the original Tango research also rates 2B as more impactful defensively than 3B.

Baseball-Reference goes year-on-year, based on how much offense teams are willing to give away for “average” defense at each position.

Good shout on looking the proper rates – I was working backwards from the /162 on the player pages, but B-Refs adjustments are /150.

For Whitaker’s career, 3B were at:

+3 in 77-78

+2.5 in 79

+2 in 80-81

+1.5 in 82

+1 83-94

+1.5 in 95

TL;DR:

Regardless of what method you use, 2B are clearly held to a higher defensive standard than 3B.

Further, anyone who claims the opposite is either uninformed or lying.

No, the positional adjustment made by Baseball Reference is consistently higher for second basemen than third basemen. That is completely separate from saying that second basemen are held to a higher defensive standard, especially since BREF’s positional adjustment is based on offensive performance, not defensive.

Meanwhile, the positional adjustment used by FanGraphs is not higher for second basemen, and I gave multiple real world examples showing that teams put inferior defenders at second rather than third. I also explained why teams put inferior defenders at second rather than third. It is a fact that balls hit to third base average a significantly higher velocity than balls hit to second base. It is also a fact that throws from third base average a significantly farther distance than balls hit to second base.

Holy shit!

The troll/so dumb it doesn’t know it’s a troll doesn’t know what positional adjustments mean!

Chances of self-reflection:

Zero.

It genuinely made me laugh when I read this, because you are so oblivious that you don’t realize you just made a comment that applied entirely to you.

Once again, the BREF positional adjustment is not based on defensive performance, it is based on offensive performance. BREF assigning a higher positional adjustment to second basemen than third basemen therefore does not mean that “2B are clearly held to a higher defensive standard than 3B,” as you incorrectly claimed.

It means that second base has generally been a weaker offensive position than third base.

I certainly remember trembling in fear of Craig freakin’ Biggio .. wait, no, that is not how it went.

Case in point!

Is he dumb, or is he trolling?

The jdbolick story 🥲

Thank you for proving my point about you being obsessed with me. It’s not healthy. You are not acting like a mentally balanced person.

There are still people who don’t know this? And they probably supported Jack Morris over Blyleven.

Sooner or later, Mattingly is going to be hodged (i.e., elected to the Hall of Fame after being on the ballot more times than should be allowed).

They should give Evans a chance to get hodged.

Every time I see bench Mattingly I think how he’s the size of a middle infielder in today’s game.

I miss the coiled hitting crouches of Mattingly and some other 80s stars. The crouch said “hitting scholar.”

He honestly would have been a SS if he were righty.

Fernandomania was a massive phenomenon for the sport. It is the Hall of *Fame*, after all. We also have to remember Harold Baines is in the Hall, and he didn’t even crack 40 WAR.

You can’t admit everyone to the Hall of Fame who is more deserving than Harold Baines.

Harold Baines was my favorite player for a long time, but if the HoF standard becomes “better than Harold Baines” then you are going to have to build a few extra wings to hold everybody.

It’s odd that so many people dump on the PED guys and then laugh about Baines. If there are no PEDS, Baines is one of the best players of his era and likely a slam dunk HOFr.

Are we presuming that if guys like Bonds and McGuire didn’t take PEDs that they would be worse than Harold Baines?

Genuine question. I see people say things like this all the time but I just find it hard to believe that PEDs, which mostly just increase power, longevity, and injury recovery, suddenly make guys so much better at a sport that is so heavily focused on hand eye coordination and vision that they’d just suck without them.

This is a common misconception regarding what steroids do. First, they are absolutely not used for injury recovery. That is a myth told by athletes who got caught, but medical studies like the one conducted by Papaspiliopoulos found that “the effect of local nandrolone decanoate use on a rotator cuff tear is detrimental, acting as a healing inhibitor.”

Anabolic steroids are not prescribed for injury recovery. They are primarily prescribed for hypogonadism and muscle wasting diseases.

The latter is relevant, as the tremendous muscle growth from using anabolic steroids is why athletes take them to achieve feats beyond what is possible without them. A medical study by Bhasin found that a person who takes anabolic steroids and does no exercise at all has greater muscle growth than someone who engages in weight training three times per week, while someone who takes them and exercises three times per week experiences tremendous muscle gains.

Anabolic steroids took Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson from someone who consistently finished the 100 meter sprint at around 10.2 seconds to obliterating the world record with a time of 9.83.

To illustrate how they affected Barry Bonds, consider that he hit zero home runs longer than 450 feet from 1986 through 1999. Between 2000 and 2004, Bonds hit 21 home runs longer than 450 feet.

Where did you get that info on Bonds’ home run distances?

That data came from STATS Inc., now known as Stats Perform.

Understood.

Also worth considering is that at the level of professional athletics, frequently the act of restrengthening the muscles around the affected area to the levels required is usually an equally hard process to the recovery of the primary injury, those steroids would increase the speed of that process.

Beyond that, if Barry Bonds had hit zero home runs 450 feet for his career I still very much doubt he would be worse than Harold Baines, which was more my point.

That is precisely why anabolic steroids are not prescribed for injury recovery. They dramatically increase the speed of muscle growth, which is effective if they’re building on top of existing tissue. It is not fine if they’re affecting injured tissue. The fibroblastic activity is too extreme, inhibiting the strength of granulation tissue because it is happening much too fast. The tissues formed during repair on anabolic steroids are ultimately weaker and less stable due to the extremely rapid growth.

Bonds was roughly three times the player Baines was before Bonds ever used performance enhancing drugs. He was one of the greatest players of his era and a first ballot Hall of Famer if he had retired then instead of cheating.

But you were also downplaying the effects of anabolic steroids on performance. They genuinely do “suddenly make guys so much better at a sport.” They turn above average professionals into elite professionals and they turn elite professionals into superhumans.

Nobody knows when Bonds started juicing – we only suspect. Didn’t it turn out that one guy (A-Rod?) was juicing from a much younger age than we had originally guessed ?

We know that Bonds hired Greg Anderson in 1998. Anderson would later be convicted of steroid distribution. We also know from the federal investigation that Bonds became involved with BALCO in the winter of 2000.

The data shows that Bonds was statistically declining in the late ’90s, then posted a career high ISO of .355 as a 34 year old in 1999. He surpassed that number by posting a .381 ISO in 2000. Presumably, Anderson was giving him generic anabolic steroids during those two seasons. BALCO was on a completely different level, as they custom-made much more powerful anabolic steroids, which is why Bonds’ ISO went from that career high .381 in 2000 to an absurd .536 in 2001.

That season figure is .064 higher than anyone else in the history of the sport.

Yes. Those are things we know. What we don’t know is if he simply super-sized in 1998 to get the drugs to do more than they were already doing

It’s too bad he won’t tell us. I’m just going to assume he was juicing all along until someone can prove otherwise. I’m not sure why so many people are keen to accept these guys were only juicing in the years they got caught

We have sworn testimony from his girlfriend at the time that he blew out a tendon in 1999 because he didn’t know how to use steroids.

We’re going by the available evidence. The first instance we know about of Bonds associating with an anabolic steroids trafficker was in 1998. The first instance we know about of him associating with a laboratory that developed designer anabolic steroids for athletes was in 2000.

Because that’s what the statistics suggest. Bonds’ career followed the normal progression for a Hall of Fame player, from ascension to peak to decline, until 1999. At that point he deviated in the most extreme way from the normal aging curve. You can see in the numbers where his performance was enhanced.

I think you might be misremembering a bit because no one that I can see with any knowledge has ever said that anabolic steroids are primarily a recovery tool. Some PEDs, however, were exactly that.

In particular, that is the primary benefit of using Human Growth Hormone, which is the main PED in which Bonds has been implicated. Faster-than-normal recovery time can lead to the same kinds of exaggerated muscle mass buildup because one can both work out more frequently and gain more benefit from each session.

Also, in that same timeframe training techniques were improving very substantially, so when Bonds went to leverage those benefits he was able to make much more dramatic gains than others. And nonetheless the most remarkable and memorable thing about his performance in those years was his incredible pitch recognition and selection.

And, of course, he was also hitting *against* players who were using PEDs, because we know they were widespread.

That’s an odd thing to say given that katmanisalive just said it: “the act of restrengthening the muscles around the affected area to the levels required is usually an equally hard process to the recovery of the primary injury, those steroids would increase the speed of that process.” The idea that steroids are used for injury recovery is a very common myth, which is why I mentioned studies proving otherwise.

You are wrong on both parts of this. HGH is not prescribed for injury recovery. A 2024 study by Baumgartner found that: “HGH administered to human tendon and ligament fibroblasts does not appear to positively affect cellular proliferation and differentiation.”

HGH also is not the main PED that Bonds used. Bonds admitted to using “the cream” and “the clear.” “The Cream” was a specifically calibrated mix of epitestosterone and testosterone. “The Clear” was tetrahydrogestrinone, which was a designer anabolic steroid provided by BALCO specifically for Bonds.

There is no truth to this whatsoever. I already mentioned the study by Bhasin, which showed that using anabolic steroids produces more muscle growth with no exercise at all than participants gained by weight training three times per week, while the biggest gains by far came from combining anabolic steroids with weight training.

Define widespread

Do you think a Barry Bonds comp is a legit way to have this discussion. He was clearly a superstar without steroids. But there were probably 10-25% of the league juicing their results (pitchers and hitters). It’s probably fair to say that all of them took a bit of WAR away from Baines every year

McGwire is a great comp. He’s barely a consideration for the Hall with steroids – without them he’s your run of the mill power hitter.

We don’t know but I’m not willing to extend good faith to those who did juice and beat up on guys who didn’t.

Baines was a DH with a career wRC+ of 119. He wasn’t in the top 25 of his era. Moreover, he didn’t get in via the writers. He only got in because he had multiple friends on the Veterans Committee.

But maybe 119 is 130 if you adjust for everyone who was enhancing their performance – you just don’t know how good Baines would have been on a level field.

For that matter we don’t know if Baines juiced but there’s no credible analysis that he did

Or let me ask the question : if all pitchers and players in his era had played juice-free would his stat line look better ? Yes/No

This is basically the argument for Fred McGriff, but McGriff was a much better hitter than Baines.

So were a lot of other players, like Bernie Williams and John Olerud.

Yep – this is an argument for Bernie/Olerud/McGriff/Lofton/Clark, not Baines.

This week in evidence-free whoppers….

Do we think he and jd are the same person, trying to farm up and down votes for some bizarre reason known only to them???

…but you can die trying

Do you know who else is in the Hall of Fame? Lloyd Waner

Go ahead and look up his stats, and keep in mind that he did indeed play during the live ball era.

This is by far his best argument, but it needs to have some level of statistical support. A guy like Tiant feels better to me than Fernando

His peak isn’t peaky enough and he only had seven good years.

He might do well though – there are a lot of fond memories of him