Paul Goldschmidt Is Surging

When the Cardinals traded for Paul Goldschmidt this offseason, they added one of the most consistent and potent hitters in all of baseball to a team sorely in need of a jolt. As players go, Goldschmidt was about as safe a bet as there is. From 2013 to 2018, he had posted a wRC+ between 133 and 163 every season. His wasn’t a story of constant reinvention and tinkering: he was basically the same hitter every year. He walked a lot, struck out a lot, hit for power, and ran a high BABIP through a combination of his surprising speed and consistently above-average line drive rate.

If that’s what the Cardinals thought they were adding to the lineup with Goldschmidt, the early returns were disappointing. Fresh off of signing a five-year extension, Goldschmidt scuffled through the first months of the season. After starting off the season strong with a three-dinger game in his second game in a Cardinals uniform, he put up some alarmingly pedestrian numbers. He ran a 123 wRC+ for March and April, not up to his usual standards, and it went downhill from there. He declined to a 104 wRC+ in May and a shocking 57 wRC+ in June.

Alarmingly, it didn’t look like luck was to blame. Goldschmidt’s .302 BABIP was below his career average, but not concerningly so. His strikeouts were up a hair and his walks were down perhaps two hairs from his Arizona form, but nothing about that screamed regression. No, Goldschmidt’s problems boiled down primarily to one thing: he stopped hitting for power. In his last six seasons with the Diamondbacks, Goldschmidt had posted an ISO in the top 20 in baseball five times. The one year he didn’t, he propped up his value with a whopping 32 steals and career-best plate discipline.

With half of the 2019 season in the books, Goldschmidt’s ISO was below league average, leading to a 97 wRC+. Not just outside the top 20, not just below .200 — it was a puny .159, smack dab between Amed Rosario and Nick Ahmed. As for propping up his value with steals and plate discipline, he had zero steals and the worst K-BB% since his rookie year. Add it all up, and he’d been worth 0.7 WAR, less value than he’d accrued in his average *month* with the Diamondbacks.

When a player declines like this, theories for what has changed abound. Goldschmidt had a slow start to 2018 as well, and back then, Jay Jaffe surmised that Goldschmidt’s difficulties stemmed from trouble dealing with velocity. This year, opinions were more varied. Maybe he had a patience problem, or a groundball problem. Maybe he got too streaky. Regardless of the cause, it seemed like time to worry.

Of course, the season doesn’t end after June 30. Admittedly, the only reason I gave you statistics through that date was to make the transition more dramatic. Transition to what, you ask? Since June 30, Goldschmidt has been, well, he’s been Paul Goldschmidt. He’s batting .302/.350/.635, good for a 150 wRC+. His walks haven’t rebounded, but his power has returned with a vengeance (.333 ISO), and his 12 home runs have him batting above .300 with only a .313 BABIP. This version of Goldschmidt isn’t quite the same as his Arizona peak, but he’s providing roughly the same value at the plate.

When a change this dramatic occurs, there are four stories we can tell about it. One, maybe he was getting unlucky before, and his true talent level is what he’s currently displaying. Two, maybe he’s getting lucky now, and the earlier “cold” streak is the right level. Three, which is the most common story, is that he was getting unlucky before and lucky now. Four, maybe something changed.

Let’s cover whether he was getting unlucky first. In a very narrow sense, we could just look at xwOBA, the Statcast metric that approximates wOBA by looking at batted ball data. Using this as our guide, Goldschmidt was indeed getting unlucky — but just barely. He compiled a .323 wOBA and .343 xwOBA through June 30. He was doing worse than he should be, but not by much. That .343 xwOBA works out to around a 112 wRC+ after accounting for park effects.

Nothing looked particularly strange in the more granular metrics, either. Goldschmidt was indeed less patient, swinging at 45.4% of pitches he saw, on pace for a career high. He was making contact with pitches in the strike zone a career-low 79.5% of the time. The walks and strikeouts, in other words, were deserved. He pulled grounders roughly in line with his career average, and turned fly balls into home runs 17% of the time, a disappointing but still above-average rate. Add exit velocity to the home run data, and it looked roughly like he deserved his home run rate — nothing lucky or unlucky to see here, in other words.

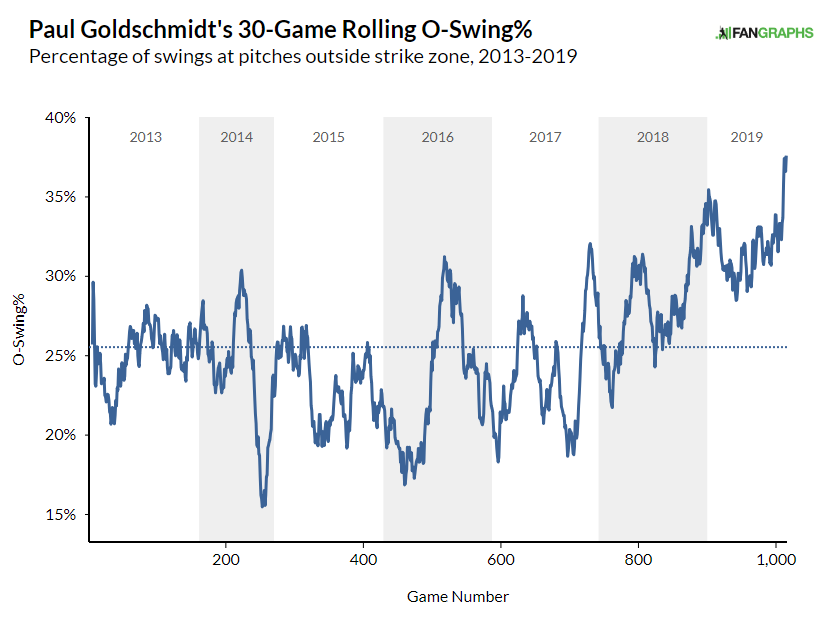

Okay, so Goldschmidt wasn’t getting particularly unlucky in the first half of the season. Has he been getting incredibly lucky since? By our standby wOBA/xwOBA comparison, it doesn’t look like it. Goldschmidt has hit to the tune of a .407 wOBA since July 1st, basically what his .401 xwOBA suggests is fair. His plate discipline looks reasonable as well. He’s been swinging at absolutely everything — his O-Swing% is 36.9%, a huge outlier over the course of his career that explains the decreased walks:

Some of the increased production, of course, comes down to a spicy 27.9% HR/FB rate. That rate has increased markedly from earlier in the year, driven largely by hitting the ball harder and more consistently — he’s barreled up a quarter of the balls he’s put in the air since July 1st, as compared to only 15% before then. He’s pulling the ball more in the air as well, 35% of the time against only 25% before July 1. Pulled fly balls and line drives are the best way to hit for power, and 10 of his 18 extra-base hits over this period have been pulled.

Without real evidence that Goldschmidt was getting tremendously unlucky over the first part of the season or lucky over the second part, we’re left looking for a change. One thing stands out. His batted ball distribution has changed massively:

| Statistic | Through 6/30 | Since 6/30 |

|---|---|---|

| GB% | 43.4% | 33.7% |

| LD% | 19.6% | 21.1% |

| FB% | 37.0% | 45.3% |

| GB/FB | 1.17 | 0.74 |

| Pull% | 33.3% | 43.2% |

| Cent% | 42.0% | 37.9% |

| Oppo% | 24.7% | 19.0% |

| HR/FB% | 17.3% | 27.9% |

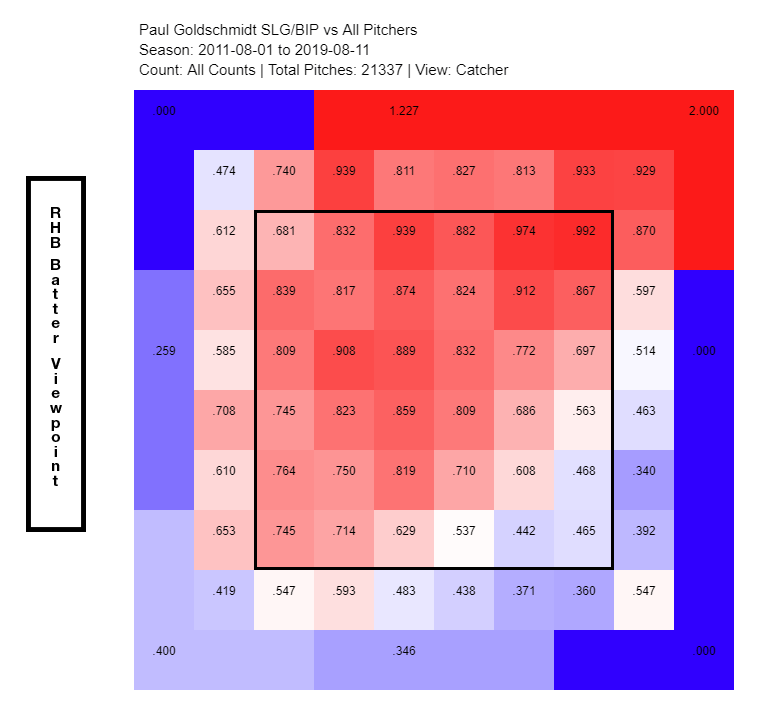

Goldschmidt has never been a fly ball revolution guy; his GB/FB ratio has never been below one for a full season. His swing is anachronistically level, designed to work with what the pitcher gives him, which means that he’s generated most of his power on high pitches:

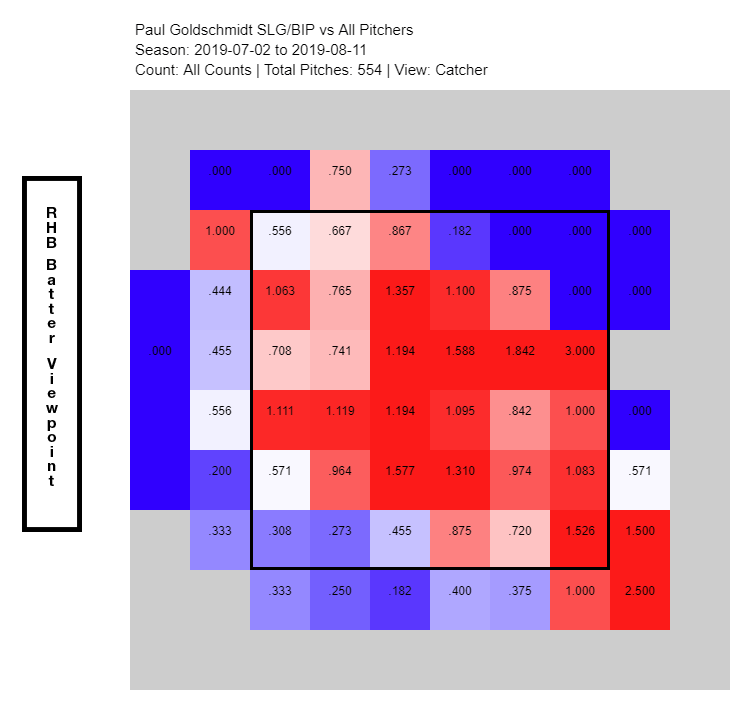

That’s changed. His power during his recent surge has come almost exclusively from the middle of the strike zone:

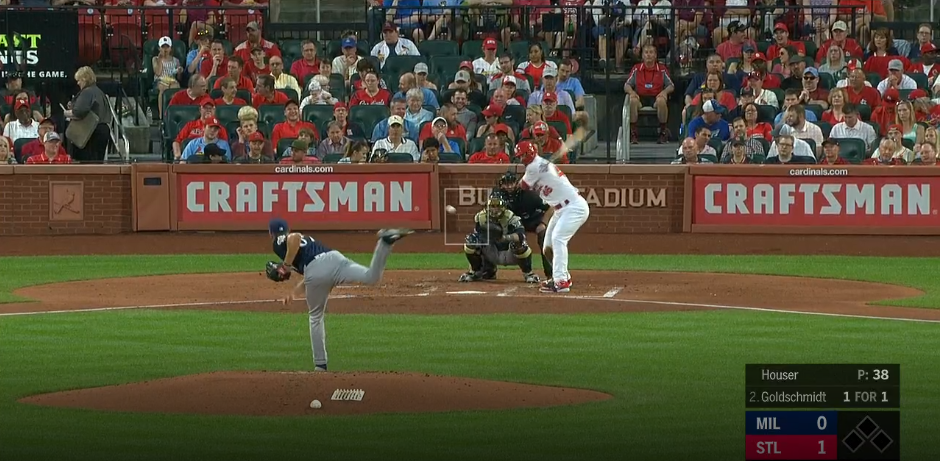

Want a demonstration of how he’s tapped into this power? Take a look at two pictures of Goldschmidt facing fastballs middle-in:

One of these balls became a weak grounder. The other was hit for a home run. I’ll save you the guesswork. Houser’s pitch, which occurred in April, became an out, while Darvish’s in late July became a souvenir. Notice anything different? To me, one thing jumps out. Goldschmidt is more crouched and coiled against Darvish, while he appears almost folded over against Houser. Watch them in real time, and the difference becomes more stark. Against Houser, Goldschmidt starts in a crouch before seemingly popping halfway out of it mid-delivery:

Against Darvish, he stays in his stance, smoothly transferring forward into his swing:

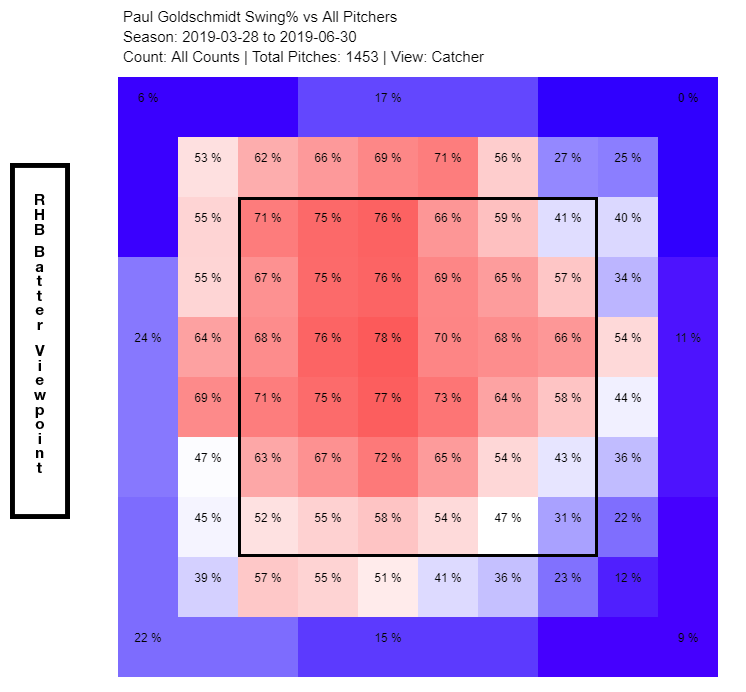

This is a tiny change, something I’m only seeing because I want to look for a reason Goldschmidt has put more balls in the air. But small changes add up. Goldschmidt has put nearly 65% of balls thrown in the lower two-thirds of the strike zone into the air since July 1, significantly higher than his career rate of 56%. He’s putting 80% of balls on the inner third of the plate in the air over that same span, and he’s started swinging at those inside pitches far more. Early in the season, he leaned inside and high but had a balanced swing profile:

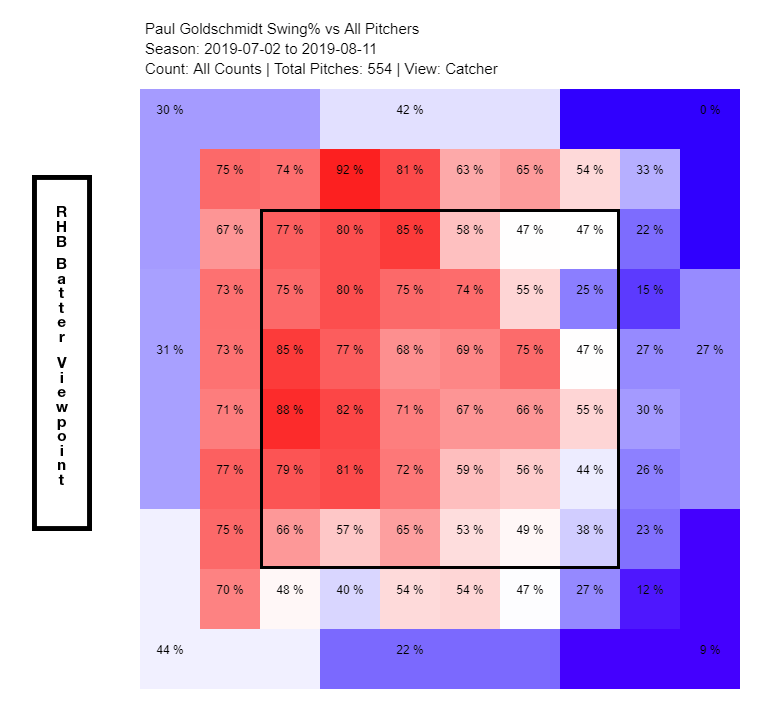

Now, rather than attack everything equally, he’s looking further and further inside:

Of course, swinging at inside pitches comes with downsides — look no further than all the swings off the inner edge of the plate. For now, Goldschmidt is managing the tradeoff, and it’s not hard to understand why. He has a career .630 wOBA on balls hit in the air, miles higher than his .258 wOBA on grounders. If the cost of turning groundballs into line drives and fly balls is marginally worse plate discipline (his K-BB is 2% worse during his recent hot streak as compared to earlier in the year), that’s a swap anyone would make.

Goldschmidt hasn’t fixed everything that ails him. His walk rate during his recent hot streak is worryingly low, and his performance on high-velocity fastballs, which Jay identified as a problem last year, is the lowest of his career. He’ll need to adjust again if pitchers counter his recent aggression on inside pitches. For a batter who was metronomically consistent for so many years, his future is startlingly unsettled.

Ask Goldschmidt himself, and he’s not convinced there was ever a reason for concern. When he spoke to Rian Watt on July 3, near the nadir of his season, he had this to say: “I wouldn’t use the word ‘concern.’ There’s always times that you struggle. This time has been a little longer than other times in my career, but that’s part of the game, and that’s going to happen. I’ve just got to find a way to make it happen out there.” In the month since then, he’s absolutely made it happen, though with a slightly different approach than we’re used to seeing from him. Goldschmidt may not have been concerned, but he seems to be adjusting.

At the moment, the chaos is working for him. Goldschmidt has been one of the best hitters in baseball for the past month, powering a Cardinals offense desperately in need of consistency. He’s shown, with adjustments small and large, why the Cardinals were so eager to acquire him this offseason. After all the early-season struggles and worries about age-related decline, it seems surprising, but this season has gone about how many would have predicted this spring. The Cardinals are locked in a three-way dogfight for the NL Central, and Goldschmidt’s hot bat is keeping them in the race. Who knows what will happen tomorrow, but for now, a season of highs, lows, and dramatic adjustments has ended in a predictable place.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

The opinions about the source of short-term volatility don’t seem to matter for anything. The underlying metrics vary just as wildly as the real outcomes. You can drop all of the batted ball data and get to exactly the same places. There is no inherent truth in the batted ball data – its an overly narrow view of batted balls for my taste. The one thing that is way down are his doubles – that and a depressed babip is what has Goldy having his worst year. The FB explain the babip and the lack of doubles. It is entirely possible that he hasn’t made any changes or fixed anything at any point as things will vary either way. Things never go the way players want them to go – if they did, then everyone would have a career year every year. The whole thing looks like he is hitting more balls in the air to me, which may or may not be intentional and/or sustainable. Many hitters have gone that route as the physical skills begin to decline. When you can’t make as much quality contact there is a point where it makes sense to maximize the limited quality contact you do make. Its not something the best hitters in the game do, but it can keep a player relevant for a while longer. It doesn’t really seem to be working for him, but you don’t really know that it is intentional. For Goldy it could just be what decline looks like, it could be an injury or it could be intentional. I think the FB/GB rates tell you more than the EV derivatives. it seems like the worst analysis is often rooted in EV derivatives – the Taylor Motters and Keon Broxtons of the world come to relevance through that school of thought.

I watch real baseball and I don’t see players adjusting but I do see a lot of inconsistency from game to game and at bat to at bat – just as it has always been. I see a lot of pitchers with poor command of limited repertoires – I don’t think your average arm is exploiting or adapting anything. I have a hard time believing that it is a game of chess as much as it is a game of poker which is much more dependent on luck in the short term, but lesser so over a long run. At the end of the year things seem pretty close to predictable with wild variations in between. I think if you skipped all of the modern predictive models and just used past counting stats with some consideration of lineup changes, park changes, advancing age and longer-term track record you would end up way ahead of what you would get from statcast-driven contemporary analysis. There are no profits to be made from that line of thinking though. Snake oil has always been a seller.

Real baseball? I’m not even sure what that means. What happens on the field is reflected in the numbers — both descriptive and predictive. It basically comes down to what numbers you trust.

Using “past counting stats” (with the carpton of “modern” adjustments you stipulate) is a perfectly logical approach.

Bu to end up “way ahead,” you’d kinda have to sort of … do it.

I encourage you to make the attempt.

I should however add (and back to the OP, jam-packed as it is with all this new-fangled snake-oil) that the most interesting part about all this isn’t necessarily the — descriptive – numbers. It’s Paul G’s approach. This is obviously a guy at or about the top of his game who is entirely at ease with making adjustments on instinct.

Baseball is an entrancing sport. Numbers or not.

lmao sure.

no