Rules Committee Acts To Regulate the Invasion of the Late-Inning Zombies

On Monday, Major League Baseball’s Joint Competition Committee dealt a double blow to anybody who enjoys baseball’s weirder late-inning turns, with the 11-man body making the runner-on-second extra innings rule permanent for all regular-season games and placing further restrictions on the use of position players to pitch. Both votes were unanimous, according to ESPN’s Jesse Rogers, and both rules will go into effect for this season alongside the previously adopted ones adding a pitch clock and regulating pickoff throws, prohibiting defensive shifts, and enlarging the bases.

First put into place as part of the COVID-19 health and safety protocols introduced for the pandemic-shortened 2020 season, the extra-innings rule mandates that each inning after the ninth begin with a runner on second base; some call it the ghost runner, but the zombie runner (named by our own digital dandy, Dan Szymborski) or Manfred Man (christened by Reds statistician Joel Luckhaupt) are more apt. The increased ease of scoring runs is designed to bring tied games to a quicker conclusion, thereby saving wear and tear on pitchers’ arms and reducing the amount of roster churn that occurs after lengthy extra-innings contests; often the reward for a less experienced reliever stepping up to throw multiple innings in extras is a ticket to Triple-A in favor of a fresher arm.

The new restrictions on position players pitching allow teams to turn to non-pitchers only when down by eight or more runs, up by 10 or more runs, or in extra innings. In the spring of 2019, a year before the pandemic began, MLB announced a version of this rule with a permissible margin of at least eight runs in either direction, but that was revised to “more than six runs” (i.e., at lest seven runs) the following spring before all hell broke loose. The rule was suspended under the 2020 and ’21 health and safety protocols but restored last year; in a June 4 game last season, Dodger manager Dave Roberts was prevented by umpires from using utilityman Zach McKinstry to pitch while trailing 9–4, a five-run margin. On the other side of the coin, Roberts used utilityman Hanser Alberto to pitch 10 times last season, including eight where the Dodgers held a lead, two of which occurred with margins of less than 10 runs.

The 11-member Joint Competition Committee was created as part of last year’s Collective Bargaining Agreement. Whereas MLB could previously implement rules unilaterally with one year’s notice to the players’ union, the new committee gives the players a voice in the form of four player representatives, but they’re outnumbered by the six owners on the committee; one umpire is also on the committee as well. Thus the players’ power only goes so far. Last September, the bloc of players voted unanimously against the banning of shifts and the introduction of the pitch clock, but they were outvoted on both matters, and both rules will go into effect this season despite their protestations. With both of these matters, however, the players were onboard, with Rogers reporting, “Players had concerns, as statistics were beginning to be dramatically affected by so many position players pitching.”

If that’s accurate, the players’ focus is misguided, because the rub is that the extra innings rule has a distorting effect on player stats as well, one that affects about 3.6 times as many plate appearances on an annual basis. In 2022, extra innings plate appearances accounted for 1.32% of all PA, and those against position players made up just 0.37%. The most PA by any player in extras in 2022 was 15, a lead shared by Yandy Díaz and Gleyber Torres, with Aaron Judge, Steven Kwan and José Ramírez next with 14. If you want a window into the distorting effect of those extra-inning rules, consider that Judge walked seven times in those 14 PA (six of which were intentional) and Ramírez six times (five intentional). MLB has ripped up up over a century and a half of playing extras under the same rules as the first innings — via Peter Morris’ Game of Inches, the first game longer than the regulation nine dates to 1859, 12 years before the founding of the National Association — for this?

I’ll return to that subject, but first, it’s necessary to acknowledge that the extra-innings rule does what it’s primarily intended to do, which is to reduce the number of innings per extra-inning game and greatly reduce the frequency of marathon contests:

| Year | Extra% | Avg. Extra | >11 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 8.9% | 11.04 | 2.84% |

| 2019 | 8.5% | 11.14 | 2.31% |

| 2020 | 7.6% | 10.29 | 0.67% |

| 2021 | 8.9% | 10.24 | 0.64% |

| 2022 | 8.9% | 10.22 | 0.66% |

| 2018-19 | 8.7% | 11.09 | 2.57% |

| 2020-22 | 8.7% | 10.24 | 0.65% |

I’ve excluded the extra-inning games that began as those infernal seven-inning doubleheader games from 2020 and ’21. What we see with the data above is that while the overall frequency of bonus cantos has remained more or less unchanged on either side of the zombie apocalypse rule’s introduction, the average extra-innings contest in the three seasons in which the runner-on-second rule has been in place has been 7.7% shorter than such games from 2018 to ’19. Furthermore, the frequency of games lasting longer than 11 innings is about one-quarter of what it was in those two pre-pandemic seasons. Amid the invasion of the Manfred Men, we’ve had just two games go longer than 13 innings, none in 2020 and then one apiece in ’21 and ’22, compared to 19 in 2018 and 23 in ’19.

Still, we’re not talking high frequencies. Over the past half-decade, the average team has played about 14 extra-inning games per 162-game season. In the two years before the rule change, teams averaged four games longer than 11 innings per 162-game season. Since the rule was put into place, that’s down to one game longer than 11 inning per 162, a savings of three games per team, or one every two months. All told, the rule change amounts to a savings of about 12 innings per team per season, or two innings a month.

[Update: Multiple readers have asked me about the effect of the rule change on game times, which I left out of this initially because I feared the comparison might be obscured by the overall trend towards more relievers per game. However, that usage has been pretty stable over the 2018-22 period, with a larger change in the few years before that window. For what it’s worth, extra-innings games in the three seasons since the runner-on-second rule’s implementation have averaged 224 minutes (three hours and 44 minutes), compared to 234 for the two seasons before.]

The problem is one of overkill. The mechanism of this game-shortening measure “works,” but it does so by creating a vastly different game.

| Year | RA9 1-9 | RA9 Ex | BB% 1–9 | BB% ex | IBB% 1–9 | IBB% Ex | SH% 1–9 | SH% Ex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 4.49 | 4.03 | 8.4% | 12.1% | 0.4% | 3.1% | 0.4% | 1.1% |

| 2019 | 4.88 | 4.26 | 8.5% | 11.8% | 0.4% | 2.2% | 0.4% | 0.9% |

| 2020 | 4.80 | 9.30 | 9.1% | 13.7% | 0.2% | 4.8% | 0.1% | 3.7% |

| 2021 | 4.57 | 10.55 | 8.6% | 14.6% | 0.3% | 6.1% | 0.4% | 1.9% |

| 2022 | 4.28 | 10.13 | 8.1% | 14.1% | 0.2% | 5.9% | 0.2% | 2.0% |

| 2018-19 | 4.68 | 4.15 | 8.4% | 12.0% | 0.4% | 2.7% | 0.4% | 1.0% |

| 2020-22 | 4.55 | 10.19 | 8.5% | 14.2% | 0.2% | 5.8% | 0.3% | 2.2% |

Because the zombie runner — the batter who made the final out of the previous inning — is considered an unearned run, we can’t compare ERA splits, so instead I’ve used runs allowed per nine innings (RA9). Scoring in extras in the two years prior to the change decreased by 11.4% relative to innings 1–9, about half a run per nine, because relievers are better at run prevention than starters on a per-inning basis. Thanks to the unearned gift of a man in scoring position, under the new-fangled rules, extra-inning scoring rates are 124% higher than those from innings 1–9 — in other words, more than double! Intentional walk rates, which were 6.6 times higher in extras than 1–9 before the change, are now 23.6 times higher, and sacrifice bunt rates, which were 2.4 times higher in extras before, are now 8.1 times higher. Teams have greatly reduced their reliance upon small-ball tactics in the post-Moneyball era, but put a zombie on second in the 10th inning and suddenly we’ve got an outbreak of 1968 on our hands.

That’s only a slight exaggeration. Before the change, hitter performances in extras took a dip by the equivalent of about three points of wRC+, with higher on base percentages (owing to higher walk rates) but lower slugging percentages. Now, given the general advantages of hitting as pitchers deliver from the stretch with men on base, OBPs gain about 50 points in extras, and slugging percentages remain more or less stable.

| Year | AVG 1–9 | OBP 1–9 | SLG 1–9 | wRC+ 1–9 | AVG Ex | OBP Ex | SLG Ex | wRC Ex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | .248 | .318 | .410 | 97 | .245 | .345 | .398 | 99 |

| 2019 | .253 | .323 | .436 | 97 | .233 | .331 | .394 | 89 |

| 2020 | .245 | .322 | .418 | 100 | .237 | .351 | .382 | 95 |

| 2021 | .244 | .316 | .411 | 97 | .254 | .366 | .418 | 101 |

| 2022 | .242 | .311 | .395 | 100 | .265 | .372 | .397 | 109 |

| 2018-19 | .250 | .320 | .423 | 97 | .239 | .338 | .396 | 94 |

| 2020-22 | .243 | .315 | .405 | 99 | .256 | .367 | .404 | 104 |

Again, the Manfred Man rule has introduced a whole different ballgame from what we’ve spent the previous three hours watching. Your mileage may vary as to your feelings on the matter, but to these eyes, it’s a jarring and ugly solution to a problem that barely exists in the first place. The players, however, have endorsed this route, and we know managers and executives are on board as well. All of which ought to tell us something about how little they value a given midseason game once nine innings have elapsed: “Win or lose, let’s get this over with and go pound that Budweiser.”

As for the position players pitching, even as somebody who for years has enjoyed tracking the trend, I’ll admit that it’s gotten way out of hand. It’s fun when it’s Albert Pujols or Yadier Molina taking the hill for some career-capping cameo, but did we need four appearances by Carson Kelly in 2022, or seven by Kody Clemens, who contributed exactly one strikeout to the father-son record total of 4,673?

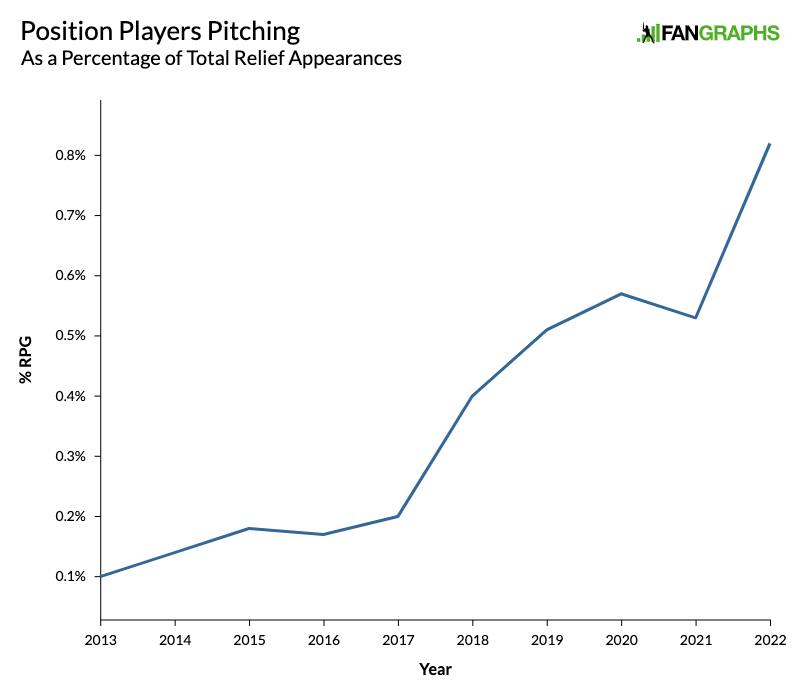

Not counting Shohei Ohtani (or, for 2019, his Angels teammate Jared Walsh), position players made 132 appearances on the mound last year, blowing away the previous year’s record of 89, which itself snuck past the 2019 record of 85. Those appearances accounted for 0.82% of all relief appearances, up sharply from 0.53% in 2021 and more than double the ’18 rate of 0.4%.

What’s more, the trend grew more frequent after June 20, when MLB finally put into effect another rule that was announced for 2020 but delayed by the pandemic and then last spring’s lockout-shortened spring training: limiting each team’s 26-man active roster to 13 pitchers. Through June 19, 0.62% of all relief appearances were made by position pitchers; thereafter, the rate shot up to 0.97%, an increase of about 57%. Within that, the trend of teams using position players to close out blowouts really gained steam. It happened five times prior to June 19 and 14 times thereafter, with the Rays’ Christian Bethancourt and the Giants’ Luis González both making multiple appearances in that context (and Alberto appearing in six of his eight games with the lead).

None of this would be such a problem if position players weren’t so conspicuously awful at the task. Last year they put up a 10.00 ERA and 8.73 FIP on the job, allowing 3.26 homers per nine, striking out just 2.5% of batters, and walking over three times as many. As old friend Eno Sarris pointed out at The Athletic, thanks to this influx of position players, the number of pitches 60 mph or slower was about 11 times more in 2022 (856) than in ’18 (78). Via Baseball Savant, batters teed off on those pitches, hitting .378 and slugging .687 in 322 PA against those slow balls in 2022.

When I checked in on the use of position players to close out blowouts last August, I suggested it might be time to adopt a 10-run rule governing such appearances, and that is indeed part of what we’re getting on that end, but I don’t think this is going to have the impact that Rob Manfred and friends do. Even if position player pitching frequencies on either end of blowouts get dialed back to 2017 levels (32 appearances totaling 29 innings), that amounts to the redistribution of just over 100 innings, a bit more than three innings per team. Whoop-de-damn-doo.

In that light, what’s odd about the players’ position as expressed via Rogers is that they’re concerned about the dramatic effect of such encounters on stats, but in all, position players faced just 671 batters all year and gave up 48 homers. That’s 671 batters faced from among the 693 players with at least one PA last year. I don’t have a full accounting of batter-versus-position-player-pitching totals — it turns out Stathead wasn’t built for this sort of thing, and doing it by hand is tedious — but if you assume that nobody with fewer than 100 PA last year faced a position player, that leaves 469 players to distribute those 671 PA among, or 1.4 per player. Nobody’s stats are being distorted to any noticeable degree by this; I did account for all 48 homers surrendered by position players in 2022, and only four (Corey Dickerson, Ha-Seong Kim, Giancarlo Stanton, and Wilmer Flores) even had two such homers.

Whatever fear the players have that somebody else somewhere is getting an easier ride than they are (all too common in our politics outside the game) is unfounded, the result of a cognitive bias that overestimates extreme events. Hitters aren’t padding their stats for big arbitration wins by adding five garbage-time homers against position players, and even if they were, it’s not like those are coming against pitchers similarly striving for bigger paydays. Neither Alberto nor Clemens are going to lose an arbitration case over their pitching stats. But some poor schmuck who pitches a couple innings of mop-up in an 8–1 game might get that ticket to Scranton-Wilkes Barre or Albuquerque just as surely as he would by throwing innings 12 and 13.

While the total number of plate appearances against position players in 2022 amounted to fewer than Judge himself made (just to pick one obvious point of reference) by comparison, players combined for 2,395 plate appearances in extra innings, again about 3.6 times as many as they took against position players. Both involve hitting in what we can generally call 10-runs-per-nine environments, but it’s pretty obvious which is having the larger effect.

In all, this mostly boils down to much ado about nothing. Taken together, these two rules address what amounted to roughly 2% of all plate appearances in 2022. Somehow, these encounters — most of which occur late at night, after reasonable people have gone to bed — are keeping the commissioner up in the wee hours as he strives to find new places to stick his greasy fingerprints on the game in the name of pace of play. Lucky us.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

I think I’d prefer a shortened extra innings (maybe out to 12?) and then declare a tie.

Or just declare a tie at the end of 9.

Or let’s just go full HR Derby, because who doesn’t want to see some dingers?

Personally, I’d rather learn the terrifying truth.

I’m all here for ties in the regular season. It’s totally okay that some games end in a tie!

Except for the part that there are no ties in baseball. Baseball has become pretty unrecognizable so I guess anything seems like a reasonable idea at this point. Maybe they should just play rock, paper scissors at home-plate for the outome instead of playing. It they tie twice, then it is a tie.

I suspect that most progressive baseball fans would prefer that they just do an OOTP sim and use that. For most fans I think that would do just fine. The betting/stats are 90% of anyones interest at this point.

Yeah there are no ties in baseball because teams always play until there is a winner. There are no ties because the rules do not permit it. That’s somewhat independent of whether it’s a good idea. Personally I would be totally in favor of it in the regular season. Games are super long already, and I would prefer a method of shortening them that doesn’t actually change the mechanics of the game.

Actually there are ties in baseball, the most recent being a tie between the Cubs and Pirates in 2016.

Just do it after 12 innings, even 11, or even 10! I love extra innings, free baseball!

yeah I would be in favor of one regular extra inning, tie after 10.

Yeah I am not in favor of declaring games tied after nine innings, but I would vastly prefer it to this nonsense. If you don’t want to keep playing baseball until someone wins, just… don’t!

(Choosing some number of extra innings greater than zero would inevitably just feel arbitrary, I think?)

Choosing a number of extra frames is not really that different from a shortened overtime period, which the NBA, NFL, NHL and most premier soccer leagues have.

I’d be in favor of 12 innings and call it a tie.

And by the way, it’s not like baseball doesn’t already have ties. It takes a fairly uncommon circumstance – a regulation game suspended with the score tied and no opportunity for a makeup – but it happens every now and then. The Pirates and Cubs played to one in 2016.

Soccer?! Baseball does not need to try to be like other sports. They should made an XLB with a bunch of dumb rules and then nobody can watch that.

Twelve would make the most sense, I think. It doesn’t feel (too) arbitrary to add another set of three innings to the initial three sets.

Better yet, if you hate baseball so much then why care at all. Why not leave the wins and ties to the people that want to be there? It is insane that people that don’t want to watch are driving this…

Personally I’d prefer the system that existed for the first 150 years of the sport’s history as it worked just fine. How the league has managed to convince fans that less baseball is a good thing I will never understand.

“I’d prefer the system that existed for the first 150 years”

Someone who isn’t me is gonna dunk on you for stepping on this rake. I don’t think you teed it up on purpose but enjoy being on the poster.

You have not made anything remotely resembling a point. Do you have one?

i’m pretty sure he is referencing the pre-integration era

Perhaps, but that’s why the poster said 150 (which encompasses many post-integration decades) rather than, say, the first 70 (lily white) years.

Did the integration of the major leagues have some effect on the rules for extra innings? Or is this just a game where we compete to see who can deliberately misinterpret something the worst

I don’t think they have convinced anyone that what they have done is good. I think you have a bunch of people that hate tradition and they are on board for any change ni matter how silly it is. I have never met a real baseball fan that likes any of these new softball style changes. I have observed people that read an article or watched some little story (social media fans) on it and are willing to parrot it as exciting and cool.

I think it’s entirely possible to not like the current set of changes (the auto runner) and also think the previous rule set was lacking.

The appeal to “real baseball fan” as a concept is not useful or helpful. It’s a vague handwavy thing that makes it easier to “otherize” people who have a different opinion on things.

Your anecdotes aren’t as nearly as effective as the weight you put on them in your comment.

But it’s not less baseball. I’m fairly certain the average 9 inning game in 2022 took longer than the average 12 inning game over the first 150 years of the sport’s history. If you could reliably play 12 innings in 3 hours I don’t think there would be an issue, but last year you were lucky to get 9 innings completed in 3 hours.

Ugh, no! Ties would be even worse, while a home run derby changes the rules even more drastically.

Eh. I thought some levity would be nice, and I was certain there’d be enough of us who know the Simpsons reference.

I come for all the stars!

ARIAGA!

ARIAGA II!

BARIAGA!

ARUGLIA!

and

PIZZOZA!!!

It’s all here! Fast-kickin, low-scorin, and ties? YOU BET!

Nailed it. No sport needs any type of regular season OT. Just have ties. It’s fine.

Yes, please ties after 12 innings! Runner starting on second base just doesn’t make sense. It breaks the basic rules of baseball. To follow this logic, MLBs next ‘solution’ would be to issue walks on 3 balls and strikeouts on 2 strikes. Garbage.

Each team would only have mabe 3-5 ties a year out of 162 games so it’s not like MLB would become the NHL. Would also be really cool to know you are down to your last out in a tie game bottom of 12th.

or just play a real baseball game… crazy idea I know!