Some of the New Roster Rules Are Garbage

On Wednesday, Major League Baseball made official a handful of rule changes that had been in the works for nearly a year. In case you missed it while following the latest twists and turns of the Astros’ sign-stealing saga or the excitement of pitchers and catchers reporting, here’s the full press release, which spares us from having to retype it:

Rule changes for the 2020 season were announced today by @MLB. pic.twitter.com/cXZrFzHv3F

— MLB Communications (@MLB_PR) February 12, 2020

The three-batter minimum rule — and the existential threat it poses to lefty specialists — has been the most discussed of these changes. Our own Ben Clemens illustrated that it won’t matter all that much, a conclusion supported by Sam Miller’s examination, while other analysis such as this article by Tom Verducci and this one by Cliff Corcoran suggest it could have a negative impact.

The changes to the injured list and the service time tradeoffs that come with the permanent 26th man and the limited September roster size can bear closer analysis, but the rules that have my attention today — and this should be no surprise if you’ve been reading my work here — are the ones concerning position players and two-way players. By themselves, they won’t amount to much, and while they do close the loopholes that come with the 13-pitcher limitations on the new 26-man rosters, those are some pretty narrow loopholes to begin with. What they really do is stamp out a bit of novelty, not that the sport needs further encroachment by the Fun Police.

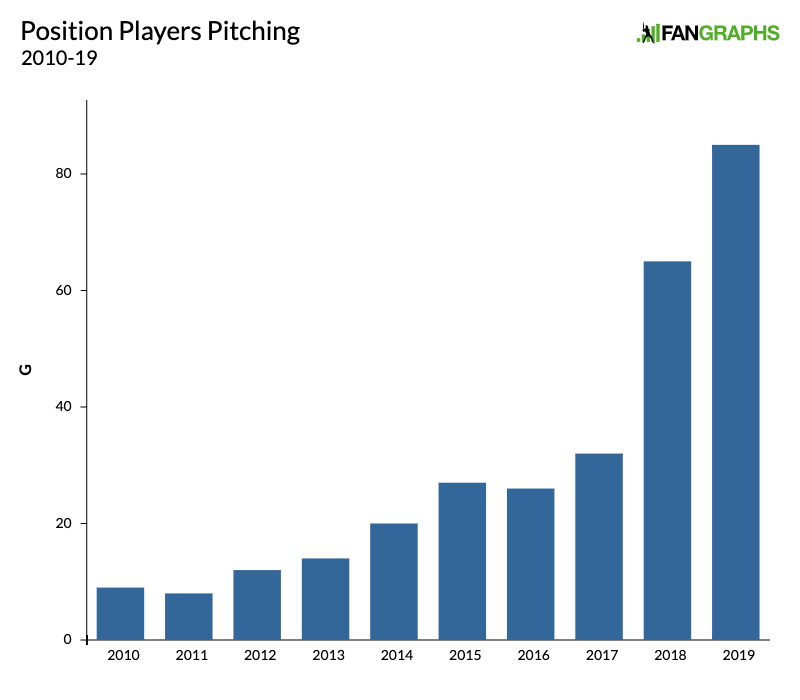

Traditionally, a position player pitching appearance has been a break-glass-in-case-of-emergency desperation move (generally in extra innings) or a lighthearted farce that draws attention away from an otherwise unpleasant blowout. Through some combination of higher-scoring games, higher per-game totals of relievers, concerns about reliever workloads, the reduced stigma of this particular maneuver, and — a factor I had not previously considered, but one Craig Edwards brought to light — an increasing number of noncompetitive games caused by a lack of competitive balance — the rate of such appearances has accelerated in recent years. Depending upon how you feel about the trend, last year marked either the peak or the nadir of the position player pitching phenomenon:

In 2019, position players took the mound 85 times, nearly as many as 2015-17 combined (87). The previous single-season record of 65 such appearances was surpassed on August 7, when the Tigers’ Brandon Dixon took the hill, and it took a September slowdown (just two such appearances) after a breakneck pace in August (a record 26 such appearances) to keep the total from approaching 100. The August 15-21 stretch saw a position player take the mound every day for seven straight days, an unprecedented streak, during which I wrote this roundup.

For those totals above and throughout this piece, I’ve excluded two converts to pitching: former outfielder Jason Lane (three appearances in 2014, seven years after his last major league stint) and former catcher/utilityman Christian Bethancourt (four appearances in 2017, when he played just one-third of an inning at another position). I’ve also excluded a trio of double-duty players: Angels designated hitter/pitcher Shohei Ohtani (10 starts from among his 104 total games played in 2018), Angels first baseman/pitcher Jared Walsh (five relief appearances from among his 31 total games in 2019), and Reds pitcher/outfielder Michael Lorenzen (73 relief appearances and 29 outfield appearances in 100 total games in 2019). We’ll come back to them.

In those 85 appearances, a total of 55 different players combined for 89.3 innings, just shy of the 92 innings such players sopped up in 2017-18 combined; this was the first year that position players averaged at least one inning per outing since 2012. Their collective performance was suitably ghastly: an 8.76 ERA and 8.69 FIP, with just a 5.8% strikeout rate against a 9.4% walk rate. They combined to serve up more homers (32) than strikeouts (25), yielding long balls at a rate of 3.2 per nine. They were terrible, sometimes amusingly so, but by the end of the season, the novelty of 70-mph fastballs had worn off, at least to some degree.

Virtually all of these appearances were desperation moves that had no effect on the outcome. Just four appearances out of 85 came in wins, three of them by Russell Martin, who threw scoreless innings to wrap up victories in games the Dodgers won by nine to 14 runs. The other one was a 16th-inning appearance by the Orioles’ Stevie Wilkerson, in which he earned a save against the Angels on July 25 — the first save recorded by a position player since the stat became official in 1969. Incidentally, Martin, Wilkerson, and the Astros’ Tyler White tied for the MLB lead with four pitching appearances apiece.

The other 81 position player pitching appearances came in losses, of which 13 were decided by six runs or fewer, which is to say close enough that they wouldn’t have been allowed under 2020 rules. Of course, some of those non-pitchers pitched in to widen those final margins, so it takes a bit of post-Play Index massaging to get an accurate count of how many of these players entered games with margins of more than six runs. The answer, which I’m sure had been keeping you awake at night, is this: 65 out of those 81 players entered with their teams down by more than six runs.

We can throw in the three aforementioned Martin appearances, all permissible because the Dodgers were ahead by more than six runs, and the two extra-inning appearances, one by Wilkerson and the other a two-inning August 2 outing by the Phillies’ Roman Quinn against the White Sox; he entered in the 14th and took the loss in the 15th. Thus 70 out of the 85 position player appearances would have been allowed under the new rules, while 15 would not have been. In 10 of those 15 games, the margin at entry was six runs, with an average leverage index ranging from -.003 to .001. Thank heavens we won’t have to endure such mockeries this year.

Note that extra-inning instances of position players pitching are quite rare; we’ve seen just 17 of them over the past decade, with no more than three in any season; there were three in 2018 and also in ’14. Four games featured multiple position player appearances, most memorably the 17-inning May 6, 2012 game in which the Orioles’ Chris Davis got the win and the Red Sox’s Darnell McDonald the loss; the other three times, it was one team going to the well twice.

Note also that when this Very Important Rule was initially announced last March alongside some rules that were put into play for 2019 (such as the reduction from six mound visits to five), the permissible margin was eight runs — in other words, “more than seven,” instead of “more than six,” to stick with the parallel construction of the announcement — in either direction. That would have run the count to 23 appearances from 2019 that would not be allowed in 2020.

Given that the proliferation of position player pitching appearances over the past few years is a reminder of the increasing instance of noncompetitive games and noncompetitive teams, you can understand why MLB would want to limit them instead of actually addressing the underlying issues that disincentivize winning. But like so much else offered up during commissioner Rob Manfred’s regime, this still feels like a solution in search of a problem. The difference between 70 position player pitching appearances and 85 is one fewer every 12 days. Unless you’re a weirdo who keeps tabs on such things for professional purposes, you’d never notice.

As for the two-way players, the rule’s requirements — again, that’s 20 innings pitched and 20 starts at a position (including DH) with at least three PA per game — means that only Ohtani qualifies as such a player, and that’s because of an exemption in the form of the parenthetical inclusion of the 2018 season; recall that due to his late-2018 Tommy John surgery, he did not pitch last year. Neither Lorenzen nor Walsh would qualify as true two-way players under this rule, which means that unless their respective teams wanted to adhere to the position players pitching limits, they would count towards the 13-pitcher allowance. That’s no big deal for Lorenzen, whose primary job is on the mound, but it’s bad news for Walsh unless he starts the season rostered as a pitcher, gets his 20 mound appearances in, and then gets his 20 position player reps in; reversing the order of those two steps, given the blowout and extra-inning limitations, would take too long.

This definition is also bad news for the Angels’ other projects in this realm, whom I covered last year, namely Kaleb Cowart, Bo Way, and William Holmes — not that any of them is a threat to crack a roster anytime soon given their 2019 performances and previous experience. The righty-throwing Cowart, who turns 28 on June 2, made 17 pitching appearances at Double-A and Triple-A but was cuffed for a 10.19 ERA, with 15 walks to go with his 16 strikeouts in 17.2 innings. Meanwhile he hit a modest .276/.330/.433 in 359 PA split between the two levels, and he was just 4-for-25 in the majors where he owns a career .176/.238/.292 line in 406 PA. The lefty-throwing Way, a 28-year-old former seventh-round pick, fared better on the mound at those same two stops, posting a 4.73 ERA in 14 appearances totaling 13.1 innings, with 12 strikeouts and eight walks while also hitting .255/.318/.391 in 391 PA as an outfielder. As he averages around 88 mph with his fastball, there probably isn’t much future for him in the pitching realm, particularly with the additional three-batter rule.

The bigger blow is to Holmes, about whom I wrote this in late August, when his season was over:

On the other hand, (literally), righty William Holmes (formerly William English), a 2018 fifth-round pick who doesn’t turn 19 until December 22, has shown enough promise on the mound to merit a spot on THE BOARD, a 40 Future Value prospect who’s ranked 27th in the system. After missing the first half of the summer with an unspecified injury, he’s been on a very regimented two-way program, DHing twice a week and pitching once. He’s hit .326/.431/.488 in 51 PA for the team’s Arizona League and Pioneer League affiliates, a big step up from last year’s .220/.325/.260 in 117 PA as a DH in the AZL. [Eric] Longenhagen reports that Holmes is raw and has struggled with pitch timing and recognition, noting that his progress may be slow given his dual focus but could be accelerated by a hitting-only focus if he reaches innings limits. On the mound, building up from 15-20 pitches to 50-60 per outing, he’s posted a 5.48 ERA with 32 strikeouts and 18 walks in 21.1 innings spread over eight appearances, seven of them starts. He’s started seven times, the last of which was a four-inning, seven-strikeout performance in his Orem mound debut on August 31. Longenhagen, who witnessed his final Arizona start, came away impressed, reporting that his fastball ranged from 92-95 mph, and he flashed a plus changeup and above-average breaking ball. Of this group, he’s clearly the one to watch.

Obviously, he’s a ways off, and by the time he becomes big league-relevant, he may have chosen one path or the other — or this dumb rule may be gone. The player likely to feel the greatest impact of this rule is the Rays’ Brendan McKay, the overall No. 4 pick out of the University of Louisville in 2017. With his pitching far more big league-ready than his hitting, McKay made his major league debut last June 29 and finished with 13 appearances (11 starts) totaling 49 innings, with a 5.14 ERA but more promising peripherals (4.03 FIP, 25.9% strikeout rate). His workload was just small enough to keep him rookie-eligible, and the command-oriented 24-year-old southpaw now ranks 17th on our Top 100 Prospects list, and he is still considered a 60 FV prospect on the mound. He’ll compete for a rotation spot this spring but may well start the year back at Triple-A Durham.

Though McKay played 49 games at first base in 2017-18, the Rays limited his non-mound work to DHing last year, and he hit just .200/.298/.331 in 168 PA at Double-A and Triple-A; in the majors, he batted as a pitcher in two interleague games, started as a DH once, and pinch-hit three times, going a combined 2-for-10, highlighted by a pinch-homer off the Red Sox’s Trevor Kelley on September 22. As with Walsh, to count as a two-way player for roster purposes, he’d have to get his 20 pitching appearances in first and then take up a chunk of time as a DH or first baseman, which probably ain’t happening given the team’s depth and competitive aspirations. More likely, going forward he’s a pitcher who provides an extra bat as a pinch-hitter or DH.

As for Hunter Greene, who was chosen by the Reds two picks ahead of McKay in 2017 and touted as a potential two-way option at the time, his days as a shortstop are done. While he DHed seven times in 2017 to go with his three pitching appearances, he spent all of 2018 as a pitcher, not once taking a plate appearance, but he injured his UCL late in the year and then underwent Tommy John surgery last April 9. He’s still just 20 years old and rates as a 50 FV prospect who placed No. 77 on our list.

As with the new position player pitching rule, by itself the two-way player rule appears to be overly restrictive but won’t amount to much. What the two rules do in the context of the whole slate, however, is create complicated exceptions to the 26-man/13-pitcher roster rules, doing away with the cases where teams carry 14 true pitchers, which becomes less practical given the three-batter minimum anyway. With that restriction in place, I’m not sure any of these additional rules is actually necessary. They’re just one more way for the Manfred regime to drain a little bit of fun out of the game and to look busy while failing to address more pressing concerns.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

Can you change a player’s designation on a game-by-game basis? McKay, for example, could be a “pitcher” on the days he’s scheduled to start, and be a “position player” on the other days. That would require the Rays to shuttle guys on and off the 26-man each time they switch, I guess, and that’s a giant hassle. On the other hand, if they had two such players they could alternate those designations pretty easily.

The 20-start requirement sucks. They could accomplish the same thing with a PA floor, excluding PAs on days when a pitcher starts. That way it’s only counting PAs where they guy was chosen specifically for his bat.

From my understanding no there isn’t a way to do so. And I guess practically that makes sense. A team could just always declare yesterday’s starting pitcher a position player and in essence carry 14 pitchers.