The First Pitch, for a Change

Don’t you just love the first pitch of a ballgame? I do! It’s a weird little world of its own, separate from the rest of a game in how both sides agree to approach it. Sam Miller wrote about it. I wrote about it. It’s remarkable: the pitch is almost always a fastball. This year, 97% of the first pitches of a game – by the home or road starter – have been fastballs. 95% have been fastballs dating back to 2008, the first year of the pitch tracking era.

Not only is it usually a fastball, it’s usually a medium-effort fastball. 71% of first pitch fastballs in the last two years have been slower than a pitcher’s average velocity for that game. 88% have been either slower than average or within half a tick of average.

Only a select few pitchers come out firing. That list includes Matt Brash, the king of maximum effort, who throws every pitch like it’s his last, which might explain why his five game-opening fastballs have been, on average, 1.1 mph faster than his overall fastball velocity. It’s not just him, though: Logan Webb has a little extra (0.9 mph, to be exact) on his first pitch. Logan Allen throws a ton of four-seamers, and throws 0.8 mph harder on his game-opening pitches. Zach Eflin has a bonus three-quarters of a tick. Pretty much every opener comes out throwing hard.

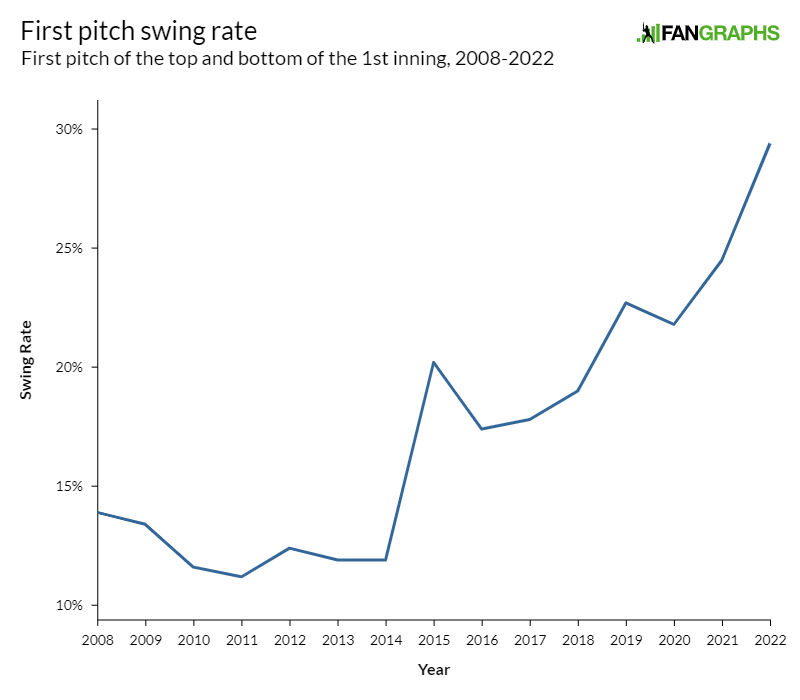

Why have pitchers historically gone to a get-me-over fastball on the first pitch of the game? It’s because hitters usually take the pitch to get their bearings. Or at least, they used to:

Yes, the first pitch is increasingly a time where batters eschew conventional wisdom and swing away. Why? It’s pretty obvious. Pitchers are throwing slow-ish fastballs almost all the time. Fastballs are easier to hit. Slow pitches are easier to hit. It’s as close to a no-brainer as there is in baseball.

What can pitchers do about this? It’s not exactly complex – they can throw other types of pitches. They don’t – again, 97% of the first pitches of games this year have been fastballs – but they can. For some pitchers, that means throwing a cutter instead of a four-seamer, sticking with something they spot well but giving it a bit more wiggle. Yu Darvish is the preeminent cutter-first starter. In the past two years, he’s thrown his slow cutter – 83 mph on average, the slower of the two varieties he uses – to kick off 42% of his starts. It’s been a fairly successful plan, too: he mostly throws them for strikes, and when hitters do swing, they miss 40% of the time.

You could try a curveball or slider, of course. Looping in a first-pitch curveball is a frequent tactic for tons of pitchers in at-bats throughout the game. Julio Urías starts the game with his sweeping breaking ball 16% of the time – again over the past two years, the time frame I’ll be using from here on out. Miles Mikolas didn’t pitch a full season last year, but he’s gone with a slider in 25% of his 16 starts. Anthony DeSclafani, Aaron Civale, Gerrit Cole, and Zack Greinke all throw a breaking pitch roughly 10% of the time. And while Kwang Hyun Kim returned to Korea this offseason, he used his slider to start a third of his games, a true delight.

You could also be Kyle Freeland, the foremost practitioner of a tactic I only learned about while writing this and now love. Freeland throws first-pitch changeups. He throws them a lot. He’s led off eight starts – 28% of his games – with changeups over the last two years. The next-highest mark, one shared by many pitchers, is two game-opening changeups. Freeland has thrown 17.3% of all the game-opening changeups across the major leagues in the last two years.

You might think that Freeland simply treats the first pitch of the game the same way he treats every other pitch. You’d be wrong. Freeland only throws his changeup 18% of the time, and only 16% of the time in 0-0 counts overall. He’s actually leaning into changeups to lead off the game, specifically picking them.

I love the tactic, as it turns out. Why wouldn’t you throw a first-pitch changeup when batters are sitting on a fastball and trying to crush it? The whole point of a changeup is to disrupt the timing of batters looking for fastballs, which is exactly what these first-pitch-of-a-game swingers are doing.

It’s a wonderful, logical idea. Just one problem: it doesn’t seem to work. Batters might be swing-happy relative to past years, but they’re not exactly hacking at anything. Freeland has thrown four of his eight changeups outside of the strike zone. Batters took all four of them – none were even close enough to be tempting. When he does venture in the zone, hitters have swung half the time – again, not great. They’ve made contact on both swings. Austin Slater even crushed a foul ball 98 mph off the bat, a sure double if it had stayed fair.

In fact, Freeland is in the midst of abandoning his changeup-to-open ways. He’s only done it once this year; it was more of a 2021 thing for him. He’s thrown boring old fastballs in four of his six starts, though he did flip in a sweet slow curve (swung on and fouled off) in one start. It’s hardly the all-changeup utopia I had imagined.

On the other hand, Freeland has been solid on the first pitch of the game. Those four fastballs he’s thrown? They were all taken for called strikes. Last year, the only two swings at his game-opening pitches were on changeups. Were hitters over-focused on his changeup? Was he mixing them in as a loss leader, knowing that a few offspeed pitches off the plate away could stick in hitters’ minds as they watched fastballs go by for strikes?

Maybe! You won’t catch Freeland giving interviews about this kind of thing, and you won’t catch the hitters he’s playing against doing so either. It’s the game within the game, and it’s valuable information to conceal. Given those ever-increasing swing rates on game-opening pitches, thinking through your first pitch is more important than ever.

Maybe Freeland’s strategy of spicing up his game-opening pitches with changeups is an overreaction, but I think pitchers will increasingly turn to similar tactics. Batters who swing at the first pitch of a game are doing incredibly well of late. In the past two years, first-pitch swings have been phenomenally valuable – 1.35 runs per 100 swings, which is a wild clip. That’s close to Aaron Judge’s production on swings throughout his career. And this is for leadoff hitters, not slugging behemoths.

Batters are going to keep swinging at more initial pitches – they’re glorified warmup tosses in an era where pitchers are throwing harder than ever, throwing fewer fastballs than ever, and snapping off mind-bending breaking pitches without regard to count. Pitchers need to do something about it. Will it be Freeland’s plan of warfare by deception? Darvish’s slower, bendier take on fastballs? Will it be Brash’s max-effort stylings? I’m not sure what the solution is, but pitchers are adapting to counter hitters’ most recent move. In a game that’s increasingly dominated by pitching, another small area of hitter advantage is getting squeezed out.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

I feel like a lot of the increase in first pitch swing rate the last few years can be explained by Tim Anderson.