The Old School Approach Failed José Ramírez

Nearly three months into this season, José Ramírez was one of the worst hitters in the game. On June 24, Ramírez had played in 77 games, come to the plate 328 times, and put up a 66 wRC+ which ranked 153rd out of 160 qualified batters. Only good baserunning and decent defense kept Ramírez above replacement level. Since June 25, Ramírez has come to bat 172 times and put up a 143 wRC+ and 1.8 WAR, with both figures ranking among the top 25 players in the game. Before the season, Ramírez was projected for a 138 wRC+ and 6.3 WAR, so he went from one of the worst hitters in baseball for half a season to nearly the exact player he was projected for the last quarter of a season. While slumps and streaks invariably have a lot of contributing factors, it certainly seems like Ramírez spent the first part of the season not trying to crush the game and simply flipped a switch in late June.

The dates used above aren’t exactly arbitrary. On June 25, I wrote a post entitled José Ramirez Isn’t That Far Off. In that piece, I discussed a few different theories behind Ramírez’s struggles, including too many fly balls at poor angles and failures in attempting to adjust to the shift. Ultimately, I went down a plate approach rabbit hole and concluded Ramírez was swinging and making contact on too many pitches when behind in the count instead of just looking and swinging at pitches he could drive. I concluded with this:

Ramírez simply isn’t commanding the strike zone like he used to, and it is showing up in increased swings on breaking and offspeed pitches out of the zone. Ramírez needs to be able to hunt for those fastballs in the plate, and to do so, he has to be able to avoid the breaking stuff. He hasn’t done a poor job of that relative to other players, but part of what made Ramírez a very good hitter was getting in favorable counts and taking advantage. The league might have caught up to him a little bit, but the problem appears to be more on Ramírez’s end and swinging at pitches he didn’t used to. That also means the issue could be fixable. Bad luck has certainly played some role in Ramírez’s big drop, as it might not be as bad as it appears, and if Ramírez can control the plate like he has in seasons past, he just might turn things around.

Ramírez has certainly made me look good over the past couple months, but we can take a closer look at the analysis from June and see if the reasoning still fits. First, let’s look at Ramírez’s swings by count type compared to last year, the early part of this season, and his recent hot streak.

| Ahead | Behind | Even | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 49.5% | 37.0% | 30.3% |

| Thru 6/24/19 | 50.0% | 46.6% | 35.1% |

| Since 6/25/19 | 53.5% | 52.0% | 30.8% |

He’s swinging at more pitches when ahead in the count, which is good, and he’s been more selective with an even count, but he’s also swinging even more when behind in the count. That doesn’t exactly help my theory. Ramírez’s walks are still down at around 6% and his strikeouts are at 15%, so he’s not the master of plate discipline he was a season ago when he walked 15% of the time and struck out in just 12% of plate appearances. Despite the increase in swings of late, he’s actually seen fewer pitches behind in the count than he did earlier in the season and more plate appearances have ended when Ramírez has an advantage.

| Ahead | Behind | Even | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 48.9% | 22.0% | 29.1% |

| Thru 6/24/19 | 37.8% | 30.5% | 31.7% |

| Since 6/25/19 | 41.2% | 29.7% | 29.1% |

The jump isn’t quite up to last season, but Ramírez has done a better job of attacking while he’s ahead. The change in results has been the biggest factor in Ramírez’s return to his old form.

| wOBA | wOBA Ahead | xwOBA Ahead | wOBA Behind | xwOBA Behind | wOBA Even | xWOBA Even |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | .480 | .447 | .249 | .242 | .350 | .324 |

| Thru 6/24/19 | .384 | .427 | .205 | .245 | .235 | .292 |

| Since 6/25/19 | .538 | .486 | .244 | .249 | .355 | .275 |

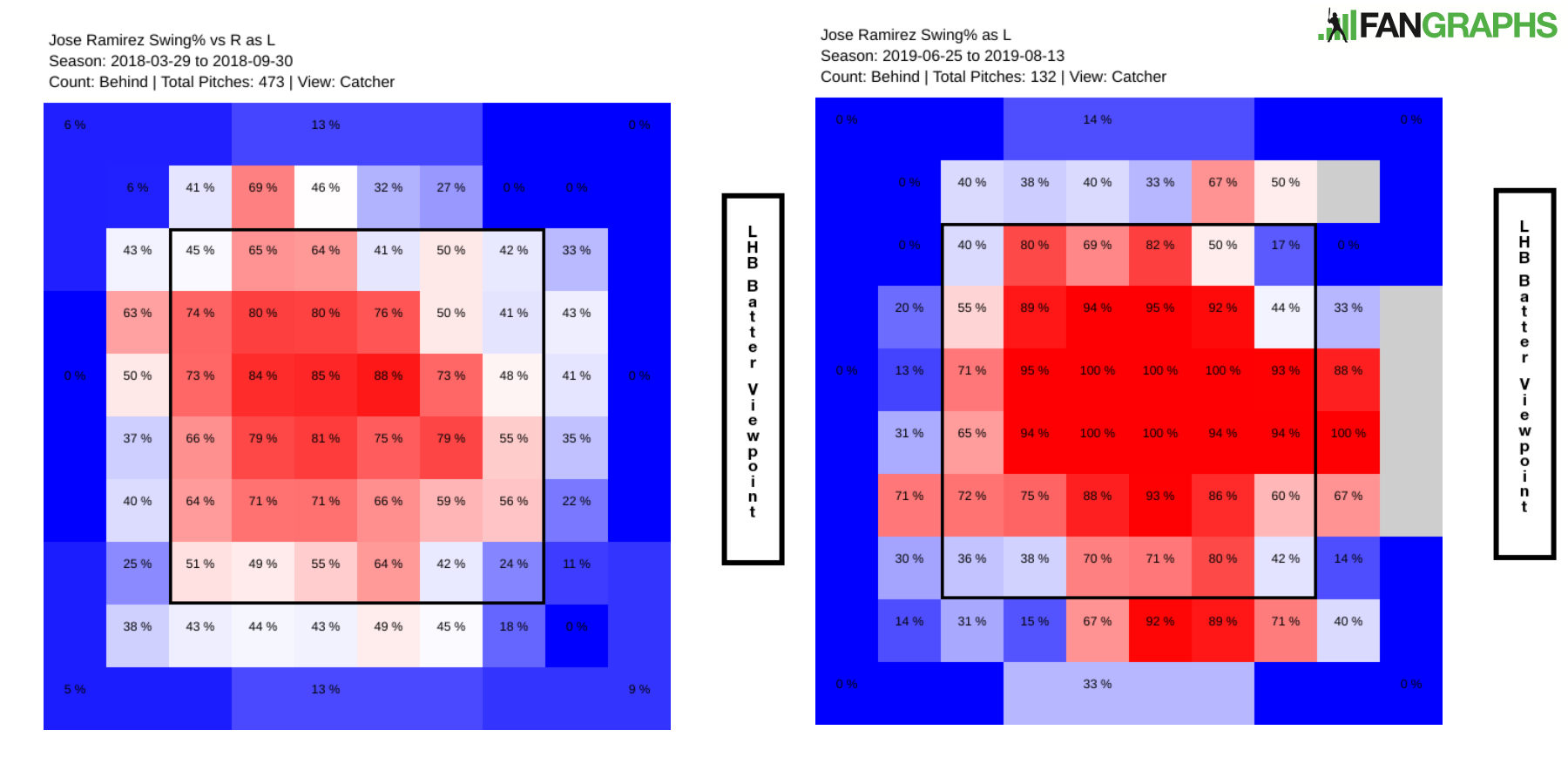

Not a whole lot has changed for Ramírez when behind or even in the count, but he’s now crushing the ball when ahead in the count, and having a greater proportion of plate appearances ending with him ahead helps make an even bigger difference. Even in looking at Ramírez’s swings behind in the count, we can get a sense of a changing approach. The heatmaps below show where Ramírez was swinging at pitches when behind in the count from the left side earlier this season compared to the last few months. Click here for the full-size version.

The Cleveland third baseman is swinging at more pitches in the middle of the plate and appears to be making a more concerted effort to also hit pitches on the inside part of the plate. That’s not just true when behind in the count. Look at how the change in pitch location of his swings has moved inside.

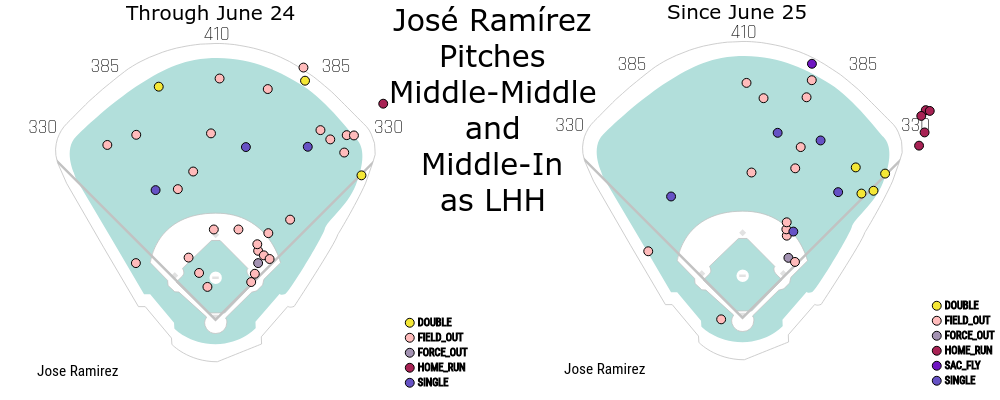

As for why he would want to make this change, we might think it is because Ramírez is trying to the pull the ball a lot more. That’s exactly what has happened, with a 48% pull rate on June 24 jumping up to a 63% pull rate in the games since. The spray chart below shows where he’s hit the ball on pitches in the middle of the plate and middle-in.

Early in the season, we see a bunch of balls headed the opposite way and a bunch of fly balls that don’t go quite fair enough. When he was getting the opportunity to pull the ball hard, he wasn’t taking advantage. Now he is. Since June 25, Ramírez has a wOBA of .643 and xwOBA of .503 in those locations compared to .213 and .292, respectively, in the early going. To see, how this works, let’s look at Ian Kennedy throw a 92-mph fastball right down the middle.

Doesn’t it look like Ramírez is almost purposefully late and trying to hit it the other way? Kennedy throws that pitch two-thirds of the time, so it shouldn’t have caught the batter off guard. Here’s a very similar pitch from last week.

While the timing of Ramírez going off is fortuitous given my article, I would never be so bold as to think Ramírez saw my article and changed his approach. The answer is much more logical.

… beat the shift. We spoke about not trying to beat the shift and just let it rip. He also acknowledged he’s been popping up a lot because he tries to go the other way and then gets beat inside.

— Rafa Nieves (@mlb_agent) June 25, 2019

I discussed these tweets with Ben Lindbergh on Effectively Wild at the time and we noted how unusual it was for an agent to publicly indicate he had been working with the player to help him. Devan Fink wrote about Ramírez’s struggles with the shift, and Ramírez’s agent acknowledging that Ramírez was trying to beat the shift by going to the opposite field and that he talked with him about pulling the ball, and that he then immediately started pulling the ball seems pretty compelling evidence.

Ramírez altered his approach to try and beat the shift, an approach some broadcasters implore players to take, and it failed miserably. Ramírez went away from his strength to try and pick up so-called easy hits and he lost his power and didn’t even get those easy hits. Hitting the ball is an extremely difficult task, and Ramírez had been very successful beating the shift by hitting the ball very hard, often over the fence without concerning himself with to the opposite field. Now that he’s embraced his old shift-beating ways, Ramírez is back to being one of the best hitters in the game.

Craig Edwards can be found on twitter @craigjedwards.

This is just a phenomenal article.

It’s…. fine.

I loved this too–was curious how many other people thought, “How come J-Ram’s agent had better advice than anyone on the CLE coaching staff?”