The Ongoing Battle for the Top of the Strike Zone

There’s a war going on across major league baseball. It’s been waged over decades, in fact, between two opposing factions of the game. Pitchers, at times aided by their catchers, want to own the top of the strike zone, the place where their fastballs have the easiest time missing bats. Hitters want to hit home runs, and the top of the zone is an ideal launching pad. But while both sides would dearly love to own the territory, they can’t both win at once. What follows are some dispatches from the front, the latest moves and counter-moves by some of the game’s best in this contested space.

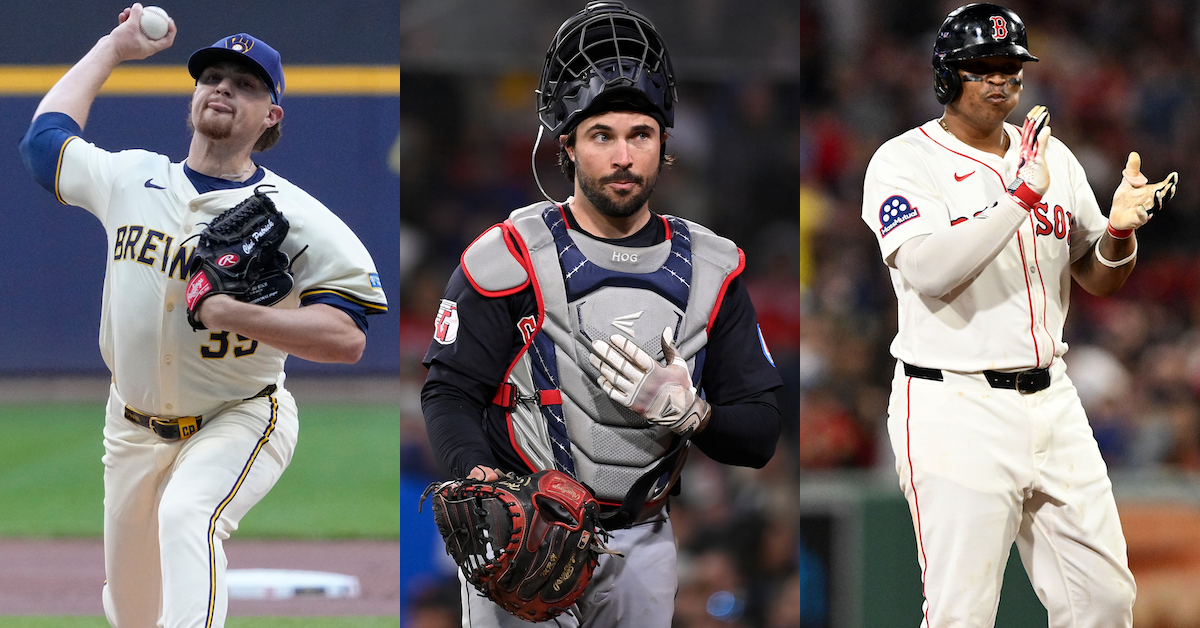

Chad Patrick lives at the top of the zone. No pitcher in baseball throws upstairs fastballs more frequently. He might not seem like the type. He’s a soft tosser in the context of the modern major leagues, sitting in the low 90s with his four-seamer and sinker, and the high 80s with his cutter. But for Patrick, shape is more important than velocity.

As Alex Chamberlain has extensively explained, the plane of a pitch when it reaches home plate is a key determinant of its success. That’s most true at the top of the zone for four-seamers. Pitches that come in high and flat act like optical illusions – the average fastball thrown to that area falls more, because it’s falling at a steeper angle.

Patrick’s four-seamer fits into that mold. When he throws it up in the zone, he gets a very shallow approach angle, negative four degrees. That’s flat even for fastballs thrown at the top of the zone, the natural mental catalog of pitches that opposing hitters call up when Patrick throws a high fastball.

It works. Want an example of what I mean by that? Picture Garrett Crochet and Tarik Skubal, two of the preeminent fastball throwers in the game. When they locate their four-seamer high in the zone or just off the plate, they’re nearly unhittable. Skubal coaxes swinging strikes on 27.7% of those pitches, Crochet 26.1%. That’s out of all pitches thrown, not out of swings. In other words, batters can’t help themselves. Even seeing a straight pitch that’s often out of the strike zone, they have no choice but to swing, and it doesn’t work out well. Patrick? He checks in at 26.3%, snugly between those two aces.

Patrick is hardly the first pitcher to own the top of the zone without premium velocity. Robbie Ray, Joe Ryan, and Clayton Kershaw come to mind when I think of this skill. But Patrick brings it to another level by mixing in more types of fastballs high in the zone. There’s the high sinker, which sounds awful but seems to work. When opponents make contact with Patrick’s, it’s been bad news for him. They’re slugging .800 when they put a high sinker in play, which, duh.

What, then, is the point of this pitch? It’s actually an excellent weapon for Patrick, and one he’s utilized very well in 2025. Put yourself in the shoes of a batter facing Patrick. He wants to throw you a four-seamer at the top of the zone, probably above the top of the zone. Look how goofy hitters look when he does it right:

That’s on the brain of the opposing hitter, obviously. This unimposing, 6-foot-1 string bean throwing fastballs above the zone? Just take them, wait him out, make him come to you. But Patrick’s sinker looks a lot like his four-seamer – he releases it from the same arm angle, at roughly the same velocity. It just happens to fall five more inches on its path home, and tail armside to boot. That’s how you get this:

That was supposed to be a ball! And Patrick is smart about when he unleashes the high sinker. When he’s behind in the count, he either uses a different pitch or aims lower. That’s just logical; when they’re ahead in the count, hitters hunt fastballs, and Patrick’s sinker is combustible up in the zone but serviceable low. To start an at-bat, though, or in an 0-1 count when they’re telling themselves “Just don’t fall for the high one again”? It’s a perfect time, and indeed those two counts are when he goes to this pitch most often. He’s even gotten one called strikeout with it this year. Poor Victor Caratini just got bamboozled:

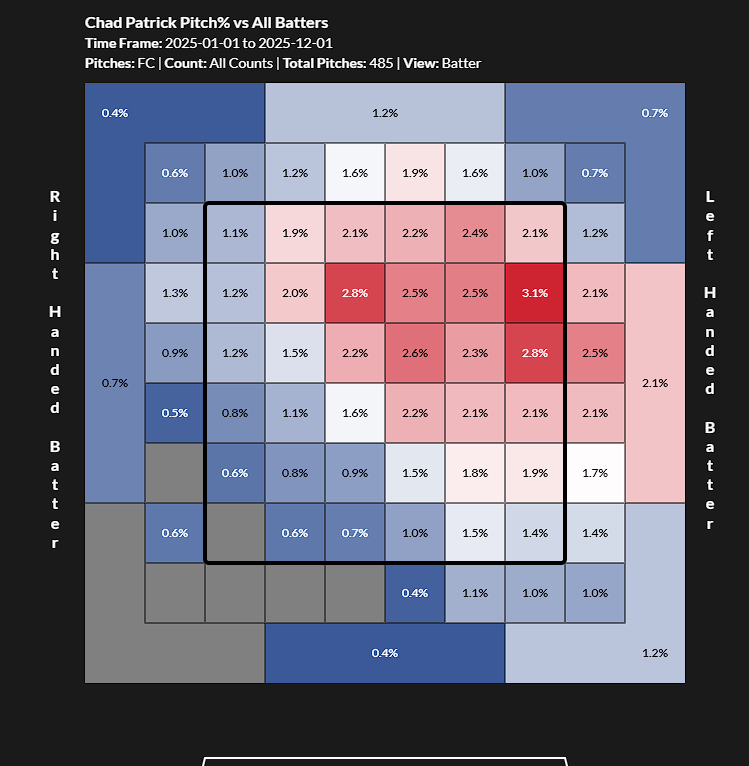

A cutter completes Patrick’s top-of-zone arsenal. Without a true breaking pitch, he uses that cutter as an out pitch, but the truth is that its horizontal location is more interesting than its vertical location. Take a look at where he throws the cutter:

The reason this works is the interplay with his fastballs. Even though his cutter has plenty of backspin – no one else in baseball throws a sub-90 mph cutter with this much induced vertical break – the velocity differential means it ends up much lower than the four-seamer for the same initial trajectory. His natural cut takes the pitch to his gloveside, too, tailing away from righties and jamming lefties. The high cutters are just a side effect of the high fastballs: Where some pitchers would pair their four-seamer with a sweeper or curveball, Patrick’s complementary offering still has a ton of backspin. The natural location, then, is high and on the glove-side corner, and he hits that spot frequently. He has a low cutter, too – a change of pace from his regular, down-in-zone two-seam fastballs – but the dance between his three fastballs up in the zone has driven his success so far.

The pitchers who best use the top of the zone, like Patrick, feast on the areas just above the rulebook zone. That’s where you can tempt a hitter to swing but not be too afraid of the consequences if they make contact – high enough that even if they’re lucky enough to hit it, they’ll probably be under the ball. It follows, then, that adding some real estate to “the top of the zone” makes the pitcher’s job much easier. Thus, catchers across the league are working harder and harder to present those high pitches as strikes. Thanks to Baseball Savant’s framing data, we can see how the percentage of high strikes called at the top fringes of the zone has increased over the years:

| Year | High, 3B Side | High Middle | High, 1B Side |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 19.9% | 35.8% | 11.9% |

| 2016 | 19.3% | 37.3% | 13.4% |

| 2017 | 16.2% | 35.0% | 16.0% |

| 2018 | 16.7% | 39.1% | 18.0% |

| 2019 | 20.5% | 47.0% | 21.7% |

| 2020 | 19.2% | 45.1% | 21.1% |

| 2021 | 20.3% | 48.4% | 22.2% |

| 2022 | 20.7% | 49.5% | 22.5% |

| 2023 | 19.2% | 49.9% | 23.6% |

| 2024 | 18.9% | 48.1% | 23.1% |

| 2025 | 14.9% | 41.2% | 18.6% |

You can unquestionably see the impact of this year’s tighter strike zone enforcement in 2025, but you can also see the league trend. Get just a few borderline pitches at the top of the zone called a strike, and you change the context of a plate appearance completely. And who’s the best at this skill? Why, Austin Hedges, of course.

So far this year, Hedges grades out as one of the best overall pitch framers in baseball. He’s at his very best high in the zone, though. He’s actually below average at presenting pitches that hit the bottom edge, but he makes up for it high in the zone. That’s on purpose, I think: Every starter in Cleveland’s current rotation works off of a high four-seamer as their primary fastball right now. Hedges is a great receiver, and he’s simply focusing his effort where it’ll be most effective.

How does he do it? First, he gets the wide edges with body position, setting up outside so that Luis L. Ortiz’s fastball looks like it’s bisecting the corner instead of off the plate:

He also uses gravity to his benefit, catching high fastballs deep and late so that even if they cross the plate too high, the point where glove and ball meet is unquestionably in the strike zone:

By starting his glove so high, leaving it up there, and letting the ball carry, Hedges is capable of making a ton of high pitches look like strikes. This one was egregious if you’re looking at the drawn-on strike zone, but watch Hedges and you can see how he gets away with it:

If you’ve wondered why Hedges continues to draw a major league paycheck while hitting .168/.233/.273 over his last 1,500 plate appearances, it’s because he’s just that good defensively. The Guardians want to win the battle at the top of the zone. They’re willing to sacrifice some offense to do it, at least some of the time – Bo Naylor is the starter even though he’s not the same kind of framing wizard. And where Hedges was once adept at making the bottom of the zone feel enormous – he was the best in baseball at that particular skill in the back half of the 2010’s – now he’s working the high corners.

As pitchers try to find more swinging strikes and catchers work to expand the zone, batters are also training their eyes up high. They know that pitchers are coming after them with high fastballs, and they have a job of their own: turn those high fastballs into extra-base hits. It’s self-defense and a plan of attack all rolled into one. If you don’t give pitchers a reason to fear throwing high fastballs, they’ll keep throwing them. And if pitchers do throw them, you better make them pay. That’s how Rafael Devers operates, at least.

Devers has a classic swing, particularly if you ignore the extremely open setup. He’s level through the point of impact, with a flatter attack angle, less downward tilt to his swing path, and a contact point aimed to left center, all the better to pepper the Green Monster. Simple physics explains why Devers has been so effective at covering high fastballs; an uppercut swing leads to swing-unders and popups, but Devers’s flat bat path is more forgiving high in the zone.

Over the past two years, Devers has put 50 high fastballs into play, at least per my definition of “high fastball.” He’s hitting .510 with a 1.082 slugging percentage on those pitches, and shockingly, both numbers hew closely to his expected statistics. In other words, he’s punishing the ball when he puts it in play. There’s the flat-path line drive single:

There’s the opposite field explosion:

Test him inside, and he’s liable to rip something into the right field corner:

I’m taking videos from the past two years, so it’s pretty easy to show you Devers succeeding. But what’s most impressive about his swing isn’t the line drives; it’s the lack of popups. Pitchers would obviously prefer to miss bats entirely, but they’ll settle for weak contact. Weak contact against high fastballs tends to come in the form of popups. Swing under the ball, and tons of your batted balls will be lazy cans of corn. A full quarter of high fastballs that end up in play leave hitters’ bats at an angle of 40 degrees or steeper, and those balls are basically always outs. They’ve produced a .028 batting average and .057 slugging percentage in the past two years – gross!

Devers doesn’t get cheated like that, though. There have been 353 batters who have put at least 25 high fastballs into play in the last two years. Of those, 317 hit popups more frequently than he does. His 14% mark is on par with guys like Luis Arraez, Nico Hoerner, and Isiah Kiner-Falefa. Where those guys are looking for singles, though, Devers is looking for more. Other power hitters do this too, with James Wood, Elly De La Cruz, and Gunnar Henderson prominent among them. Flat swings are the way to smash high pitches, and for my money, no one does it better than Devers.

You might think, given the shape of his swing and the comp to Arraez, that Devers almost never misses a high fastball. That’s not the case, though. He misses nearly half of the high fastballs he swings at. Despite the tremendous damage he inflicts when he connects, he’s only average against high fastballs. Opponents challenge him up in the zone frequently, more than about 90% of major league hitters. It’s hard to get Rafael Devers out, and particularly hard to get him to chase, so pitchers have to hunt the swings and misses where they can get them, namely up in the zone.

In fact, Devers might be the perfect encapsulation of the ongoing struggle for control of the high reaches of the zone. If he couldn’t handle those pitches, he’d get buried by them. The urge to swing is just too great, and pitchers and catchers are too good at throwing and framing them. But he’s fighting back by absolutely tattooing them when he connects. He’s not a passive target, attacked by pitches he can’t stop swinging at; he’s trying to turn pitchers’ approach back on them and bang something off of a wall.

Will the Patricks and Hedges of the world win? Will Devers and his ilk do enough damage to intimidate pitchers into venturing elsewhere? Neither of these is likely. The battle will rage on, as it has for years and years. The top of the zone is where pitchers go for strikeouts, and where hitters go for home runs. Neither side is likely to give it up anytime soon.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

What’s missing from the Devers story here is that he’s had to adjust over his career to make hard contact on those high heaters. Notably, there was that stretch in 2021 where nobody would throw him anything else—like 50 in a row during the June series with the Astros where he went 3-15 with a couple of dink singles. If I remember right, he tightened up his stance that season and went on a tear.