The Same and Yet Altogether Different

SEATTLE – My train begins to fill with Mariners fans. Most are wearing jerseys, but others are outfitted in more home-made looking fare. A young woman sports a dress covered in the team’s logo; its skirt is puffed slightly by teal tulle, with navy bows on her shoulders holding the whole thing upright. Further down the car is a man in a 1995 Division Series shirt. His snowy goatee suggests that unlike the sweatshirt I own of similar vintage, his wasn’t a thrift store find; I wonder if the one he’s wearing smells musty like mine first did. Much of the chatter is about the day finally being here, and how long they’ve all waited, how many disappointments they’ve registered in the years since 2001. I’m surprised by how little I hear about Seattle’s chances today, as if no one dares to entertain the possibility of a tomorrow with baseball, or one potentially without it.

A few stops later, a member of the University of Washington marching band steps off the train; upon seeing his regalia, a couple near me wonders if the football game, which kicks off around 2:30 PM, will cause trouble for their ride back home from SODO. “These cars can get so crowded, you know.”

As I approach the media entrance, lines snake around the ballpark, and the coffee cups and puffy eyes make clear that some of these folks have been here a while. The gates don’t open for another hour and a half, but after almost 21 years, what’s a little more waiting?

…

So much of being a baseball fan is the desire to settle comfortably. I wonder if that isn’t why fans of long-suffering franchises stick around. After all, there’s something to be said for being able to count on things, even if those things move us to stare into the middle distance. Still, given their druthers, I think most fans would offer some conditions on their settling. We like the times the game lets us sit and catch up and have a snack, but what we really want is to sink into something reliably excellent. We want the home nine there every October, long for the smugness of knowing that our season stretches beyond 162 — to feel the sting of defeat in the playoffs, but be able to shake it off with a confident “We’ll get them next year.” We want our baseball to become Baseball, the stuff of highlight reels and Hall of Fame speeches and plays immortalized with capital letters and proper nouns.

They always say that when you go to the ballpark, you might see something you’ve never seen before, and yet until Cal Raleigh hit his walk-off against the A’s to seal a playoff berth, all anyone here wanted was to see something they already had. Today, though, they wish to be marked by difference — separation from the failures of the recent past, from the team’s struggles against the Astros, from the inevitability of Yordan Alvarez. They want to sink into reliable excellence, the same and yet altogether different.

…

The ballpark advertises NFTs and league betting partners. A crypto exchange makes several appearances. Lysol ads alluding to the pandemic situate the game in time, and the smoke that obscures the mountains and presses in on downtown dislodge it; smoke is summer’s business here, not fall’s. The fans stretched out along the rail of the outfield bar wear names like Rodríguez, Gilbert, and Castillo across their backs, but there’s no shortage of Griffey, Martinez, or Hernández, either. I muse over the folks who opted not to move on from Smoak, Ackley, or, even more strangely, Healy: Are they in on the joke, or just stubborn? Maybe you have to be a bit of both to have lasted this long.

I make my way back toward the auxiliary press box, and as I pause near the statue of former radio broadcaster Dave Niehaus in the right-center field concourse, I spot a pink mirror taped to his left hand. A security guard tells me that his wife placed the mirror there so that Dave, whose bronze back faces the field, might see some of the action over his shoulder; there has apparently been talk of turning him around, but for now, this will do. Later, “Welcome To The Jungle” blares as George Kirby heads to the outfield to stretch and long toss, perhaps an allusion to Randy Johnson’s entrance in Game 5 of the ‘95 ALDS, and I wonder when this franchise will no longer be quite so marked by that series. But then I think back to when the outfield walls had signs for Eagle Hardware & Garden, and Niehaus was still in the booth, and games weren’t understood in terms of parlays, and players who were good simply because they were Mariners. Maybe they shouldn’t move on just yet, even after all this time.

…

At 12:30 PM, with the seats mostly full, the video board instructs the crowd to “Wave Those Towels.” It brings an energy to the park, and affords an important opportunity to practice. After all, that wrist action is tricky. Below me I can see a woman holding a “Refuse 22 Lose” sign; evidence of other crafts dot the crowd. Orange is sparse and stands out more brightly for its infrequency.

As the Astros are introduced, Jose Altuve and Alex Bregman draw boos that speak to 2017; the ones that accompany Alvarez address crimes of a more recent, personal vintage. And while none are met warmly, the volume some jeers reach relative to others suggests a surprising level of discernment on the part of the crowd.

Fireworks blast as the home team is introduced, adding even more smoke to the proceedings. Marco Gonzales draws a large cheer; Robbie Ray is greeted kindly. The cheers for Julio Rodríguez are loud enough to be heard through the auxiliary press box’s thick glass; the thunder for Raleigh seems almost louder. More smoke pours in.

Mike McCready plays the National Anthem. Félix Hernández takes the mound in October just as we expected, only not. His efforts today are ceremonial. The jersey he wears hasn’t seen game action. He’s retired now, cooler than the other dads in attendance but no closer to the roster, and with pitches you wouldn’t think to grade. Macklemore appears to tell the crowd to wave those towels, the annoying cousin you’re somehow still obligated to invite to family functions. It’s a Seattle playoff game.

We’re under way.

…

In the first, Altuve pops out in foul territory to Raleigh and much of the crowd stands, if indeed they ever sat down. Jeremy Peña’s fly out draws a cheer, but it is nothing compared to the noise when Eugenio Suárez sprints to track down an Alvarez fly ball in the foul territory. Three down and one fewer chance for Alvarez to end their season, though the early innings haven’t really been the issue.

Much of the crowd stays on its feet for Rodríguez’s first at-bat. You get the sense they hope they have to remain standing — to be in it, needed, as if sitting for long stretches suggests having to go home, comfortably settling as they have before. They dare not contemplate what the leisure of an easy win might feel like any more than the resigned lean of the defeated. He goes down swinging.

The conclusion of each Astros frame without a score brings a burst of energy and release; the end kept at bay a little longer. Mariners fans have become accustomed to measuring baseball in units of months and years, but now everything has been reduced to half-innings, outs, strikes even, the aperture of time narrowing until the light allowed in, the path through, is a pin prick that threatens to close entirely with each batter who reaches base.

Some fans coming back from getting beers hurry, while others amble. It’s tempting to read something into the pace, but in truth, one of the things that strikes me is how many normal moments the game offers. The playoffs of it all can snap back into focus rather quickly; it’s hardly unusual for the video board to tell fans to get loud, but a little more so for the crowd to really do so this early. Folks boo the home plate umpire all the time, but the stakes of those calls take on new resonance today.

A JU-LI-O, JU-LI-O chant breaks out as he takes the count to 1–1 in the third, but he strikes out. He doesn’t appear to be seeing the slider well.

…

The crowd periodically vents steam, with different sections yelling “Cheater! Cheater!” or “Let’s GO, Jul-IO!” above the general din. When a Trey Mancini hit by pitch call stands after review in the fourth, however, the entire assembly is back in it, and they’re furious. “BULLSHIT!” echoes from one section; towels twirl as the bases load. When Julio catches a Chas McCormick fly ball to end the threat, the whole park screams.

As the bottom of the inning opens, the tension builds. At some point this will be the bullpens’ game; eventually the home faithful will start counting Seattle’s outs. I realize I didn’t break in the loafers I’m wearing as well as I thought I had; angry blisters are starting to form. Several innings from now, as I flex my heels away from my shoes, I’ll wonder how Raleigh’s knees feel. Now though, I watch him strike out swinging after thinking he had ball four, and some in the crowd groan. Lance McCullers Jr. is only at 57 pitches. After Mitch Haniger strikes out swinging and Carlos Santana grounds out, I hear a solitary boo.

After reaching on a single in the fifth, Martín Maldonado is out on an unassisted double play; it looked like he was trying to interfere with Ty France at first on an Altuve pop up but then got caught off the bag. What a gift, and not just the out: Maldonado reaching feels terrible (he mustered a 70 wRC+ in the regular season), but then he lets out the equivalent of a loud fart, and you can’t help but laugh.

…

Héctor Neris and Andrés Muñoz begin to warm in their respective bullpens; Yuli Gurriel singles, and after Mancini flies out, McCormick reaches. Christian Vázquez comes in to pinch-hit; Gurriel’s lack of speed anchors McCormick at first. Vázquez flies out to Jarred Kelenic, and here’s Altuve with Kirby at 88 pitches. Strike one. Strike two. The ballpark is rocking, loud even in here. Altuve swings through, and the place erupts.

Bottom seven and they’re on their feet again, all 47,690. It’s a sellout.

…

In the eighth, Rodríguez doubles with two out but is stranded when France strikes out swinging. He missed a home run by about a foot, and almost dented the left field wall in the process.

…

Diego Castillo gives up a single and hits a batter; McCormick bunts everyone over. Matt Brash comes in to try to finish the ninth. After he gets Vázquez swinging, Altuve steps in. Brash throws him a slider that finishes way outside and fools the second baseman badly. The second slider takes Altuve down to his knee. In the midst of the broader game, he has slipped into a small hell. When Altuve goes down swinging, the auxiliary press box shakes. The glass has dulled the sound considerably, but it can’t do anything about the tremor.

The entire stadium screams “WE WILL, WE WILL, ROCK YOU,” along with the video board, and they mean it.

Suárez reaches on an Altuve bobble, which brings up Raleigh. Dylan Moore is in to pinch-run. Raleigh grounds into a fielder’s choice, erasing the faster runner. Haniger is hit by a pitch. I wonder if I’ve ever seen the light in the ballpark quite this way, dappled through the smoke but also at a lower angle, fading earlier than it does in Seattle’s high summer, when the light stretches into late evening. The Mariners do not score.

…

In the 11th, Paul Sewald gets three outs, with a slider that plays the way it hadn’t in the first two games of the series.

The Mariners go down in order.

Later, when Hunter Brown comes in for Houston, some fans have put shoes on their heads, though others stick with the traditional rally cap; the new approach hasn’t yet moved from cringe to nostalgia. These things take time.

…

In his first game action in 10 days, Erik Swanson draws Alvarez, a tricky assignment for someone who, just a few innings ago, the press box had speculated had been accidentally left behind in Toronto; perhaps he killed a man? The Guardians have managed two runs; their game against the Yankees is in the second inning. Here it is the 13th. Swanson gets Alvarez swinging. Seagulls are perched above the ballpark’s lights as they come on, unprepared to find so many people in the way of their pursuit of snacks. If they find Bregman’s fly out to left to be similarly bothersome, well, they can’t exactly register their objections. Fans are rocking back and forth; I imagine some legs are creaking from strain, but it doesn’t interfere with their cheers as Kyle Tucker flies out to Haniger, nor does it stop them from dancing when a sea shanty plays as Brown throws his warm up pitches. The gulls don’t appreciate the noise.

The Yankees have tied their game. After Rodríguez walks with two outs, he swipes second, his first stolen base of the postseason. He’s left standing there after France grounds out.

The ballpark does a 14th-inning stretch; “Fight For Your Right” by the Beastie Boys plays after “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.” I wonder how many more of these rally songs they have, and whether they’ll continue to work. Moore hits one deep but not deep enough. Raleigh pops out on the infield. It’s funny how, this far in, despite the tension, despite the stakes, you do have to strain against your own attention span a bit. Haniger hits a single that Peña corrals to keep from becoming a double. I briefly lose track of the outs.

Matthew Festa sets the Astros down in order in the 15th. The game has been going for five hours and 15 minutes. The Guardians and Yankees are in the sixth. The aperture reopens, and we’re flooded with blinding time.

…

It feels fitting that the first postseason game in 21 years would go to extras: you want to extend the season as long as you can, even if doing so means fighting off Alvarez again and again. The crowd quiets as Matthew Boyd prepares to face him. Alvarez pops up on the first pitch. Bregman singles. I wonder if there are still chips. It seems cruel that the hometown guy might have to take a loss. Boyd issues the first walk of the night for Seattle’s staff. Penn Murfee comes in. He is Seattle’s last available reliever; after that, starters will have to stir. Rodríguez makes an incredible catch to save two runs and the game, at least for now. Bregman advances to third, but is stranded there.

The crowd perks up as the twilight combines with the smoke to cast a strange light over the sky behind home plate. The security guard meant to keep fans out of the press box pulls out a book of logic puzzles as I pass her on the way to the restroom, but tucks it away when play resumes. Rodríguez stands in, but pops up. Why would we expect this game to hew to easy narratives?

…

Murfee continues on. The Yankees have scored two more runs; that game is now in the seventh inning.

…

I’m wondering how many people in the ballpark have begun rolling into their hangovers when Peña hits a solo shot. I haven’t been able to hear the ball off the bat all night, but this one isn’t hard to track. Kelenic makes a great diving play to rob Alvarez, but comes up grimacing. Not one run they’ll need now, but two. Bregman singles. At some point, the Dodgers and Padres got under way. Ray is pitching in relief. The crowd is quiet, seated, but still here. It’s strange now to have this game, which had unfurled in totally illogical, lengthy fashion, suddenly have an end come into such near focus. They’ll either walk it off or go home, though the threat of a tie and more innings must be considered. I’m suddenly aware of how many people are here, how many are about to file out to crowd the train. Ray strikes out Tucker, which draws a muted cheer. Gurriel flies out to end the frame.

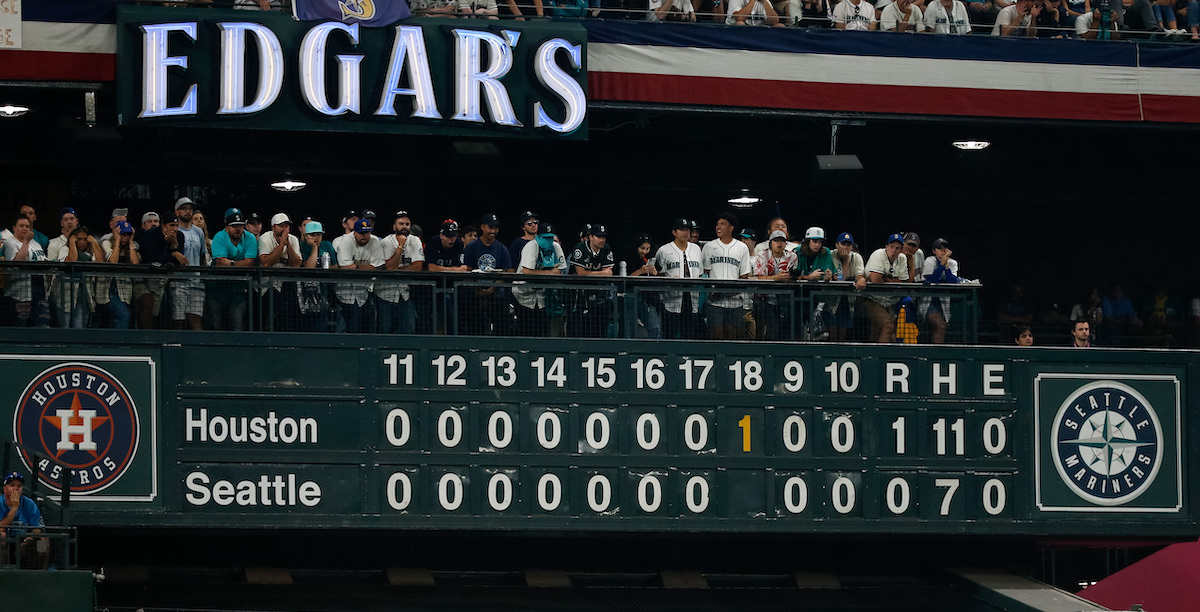

On the one hand, what’s one run? They were always going to have to score at least one run! But Kelenic has looked overmatched, and while I can’t see his face from here, he has worn the pained expression of someone who is failing, like really failing, for the first time in his life. It’s amazing how important small, survivable bruises to the ego can be to building self-esteem. He grounds out. The Yankees-Guardians game is in the eighth. Crawford grounds out. The crowd stands for Rodríguez, but they’re much quieter now. One strike. Two. He flies out to center. Six hours and 22 minutes have passed. Houston left 14 on base, Seattle 10. I wonder if Felix stayed for all 18. Logan Gilbert walks in slowly from the bullpen. Kelenic sits on the top step of the dugout. But then a “Let’s Go Mar-i-ners!” chant begins as the Astros celebrate on the field. A good many fans stay to cheer. The Dodgers and Padres are in the second.

…

As I file out through the throng of people, a young guy tells his friends, “The bullpen? The bullpen was great! And don’t forget George Kirby!” Ahead of me, someone lets out a “FUCK!” but then quiets down. Two bro types debate starting a SEA-HAWKS chant, but decide against it, preferring to linger a little longer in the shadow of October baseball. Another voice assures his pals, “Oh I’ll be back next year. Unless it’s another 20 years, then I’m out.” “We have Julio,” he’s reminded in response.

And through the smoke and memory, the dreams deferred, Kirby did secure outs. Alvarez was finally held at bay. The bullpen, which had faltered, dominated. Murfee took the loss, but only because someone had to; allowing one run to the Astros doesn’t change his resume. The crowd swelled again and again, pounding out a meter to carry the team to another day, another series. I looked around and saw people not done yet. They were defiant, emboldened by small victories and big IPAs. Ready to rush out into the fading light and return the next morning, finally able to assert the primacy of their schedule over that of the folks in the stadium next door.

It wasn’t to be Saturday, but it might be soon. Granted, the fans walking to the train have been here before, with a good team full of promise and then a long wait — an arid stretch in contrast to all that Northwest green. A good team that turns into a bad team that turns into an embarrassment. But those Mariners didn’t have Julio or George Kirby. They lacked Logan Gilbert and Luis Castillo; their bullpens faltered much sooner. They hadn’t gotten a taste for it. This team could take a tumble — teams often do — but as I am pressed into the train, it feels as if something has shifted. Toward afternoons clear of smoke, but still full of cheers and towel waving. Toward baseball that settles comfortably into October chill. Toward a game like tonight’s — one that’s the same and yet altogether different.

Meg is the editor-in-chief of FanGraphs and the co-host of Effectively Wild. Prior to joining FanGraphs, her work appeared at Baseball Prospectus, Lookout Landing, and Just A Bit Outside. You can follow her on Bluesky @megrowler.fangraphs.com.

Lovely work, Meg.

I was hoping we’d get a Meg-penned piece with the Ms in the playoffs. Sorry it wasn’t a happier ending!