The White Sox Extend Eloy Jimenez

Yesterday, White Sox right fielder Eloy Jimenez, our eighth overall prospect on this year’s Top 100, joined this week’s extension palooza (now featuring prospects!), signing a precedent-smashing extension before he’s even spent a day in the major leagues.

Eloy Jimenez’s deal with the Chicago White Sox will be for six years and $43 million, as @Ken_Rosenthal said. It will include a pair of club options and can max out around $77 million, sources tell ESPN.

— Jeff Passan (@JeffPassan) March 20, 2019

An important point here is that the White Sox appear to have leveraged service time manipulation to their advantage, as noted by Ken Rosenthal, though they’re far from the first club to have done so. Since Chicago could have gained a seventh year of control by leaving Jimenez in the minors for 15 days, the six-and-two structure means that he only gave up one year of potential free agency from what was otherwise his best (and only) alternative to taking this deal. There’s no way to know exactly how much money or how many years this saved the White Sox, but it basically took one season from the free agent column and moved it into the arbitration column, so the figure is likely in the millions. Since this exact set of circumstances could be changed in the next round of CBA negotiations, it was opportunistic of the White Sox to use this negotiating chip while they still had it.

But that doesn’t take away from the fact that this deal is predicated, at least in part, on some disingenuous public posturing from a club in the middle of a rebuild that isn’t going that well. They’re essentially holding their best prospect, and their fans, hostage, all to squeeze a little more value out of a potential franchise player in a far-off year. General manager Rick Hahn gave a non-answer last August when, during a sixth straight season in which the club was more than 15 games out of first place, Jimenez clearly warranted a call-up but was left in Triple-A. Manager Rick Renteria casually compared Jimenez to Ken Griffey Jr. last week when he was sent to minor league camp. Astros pitcher Collin McHugh shined a light on the motivations behind the situation after Jimenez was optioned. If Jimenez is on the Opening Day roster, I’m sure we’ll get some chuckles and shrugs when Hahn or Renteria are asked how he magically became major league-ready less than a week after they’d announced that he wasn’t.

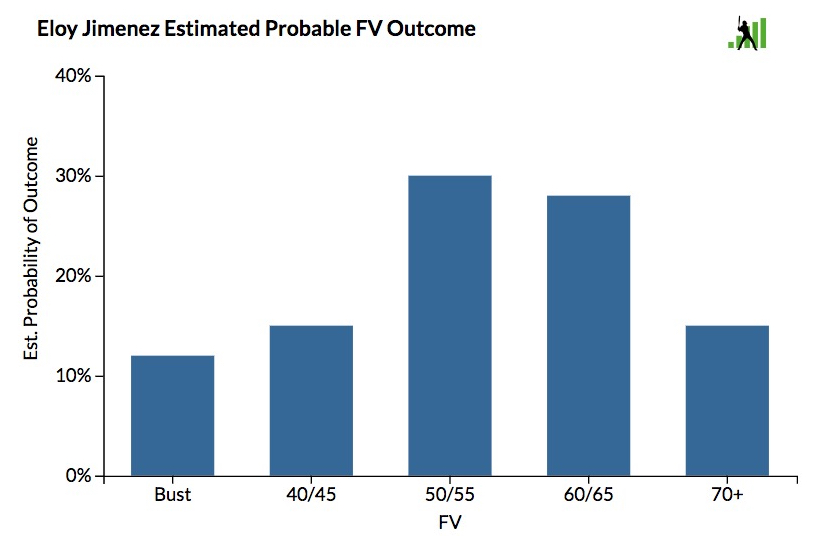

Jimenez originally signed for $2.8 million in 2013, so that money plus the roughly $1.6 million he would get making the league minimum in 2019-2021 obviously wasn’t going to create a set-for-life situation, especially after agent/buscon fees and taxes. The sort of player he has turned into (a big corner hitter who has gotten bigger and more corner-y in recent years) isn’t in demand in free agency or elsewhere, unless that player is making close to the league minimum or is hitting like J.D. Martinez. In our most recent Top 100 prospect list, we made a graph of Jimenez’s likely WAR outcomes over his cost-controlled years, using the empirical baseline of past 60 FV hitters:

Moving left to right, the percentages are 12%, 15%, 30%, 28% and 15%. The weighted average of Jimenez’s team control-years WAR is 15.5, putting him in the middle to lower end of the 60/65 group, which jives with our 60 FV grade. We basically think he’s a perennial three-win player with a chance for a season or two of production higher than that, and about a 25% chance of turning into a role player or one who fizzles out quickly (the bottom two tiers).

Craig Edwards’ research pegs a 60 FV hitter as being worth $55 million, but Jimenez is near the top of that range and research from Dan Aucoin pegs that value at about $60 million. That would cover the first seven seasons with no deal, so $43 million guaranteed with a chance at $77 million over eight years suggests that both sides did well, with Jimenez taking somewhere between a $10 million and $20 million discount (roughly a third) to get the money guaranteed, but losing little of the upside. If Jimenez captures the full value of the deal (eight years, $77 million), that figure is very close to his present asset value over eight years, or the median value of what he’s worth over that term.

The White Sox assume some risk that Jimenez ages very quickly and turns into a DH in his arbitration years, but they’re in a rebuild and things will have gone pretty poorly in other ways if that happens. Jimenez could be leaving some money on the table if he does indeed turn into J.D. Martinez, but I’m generally of the mind that right-handed hitters with heavy builds at age 22 to take the median payout, especially if they haven’t had a huge payday yet. I just wish these sorts of shenanigans weren’t what got them there.

Kiley McDaniel has worked as an executive and scout, most recently for the Atlanta Braves, also for the New York Yankees, Baltimore Orioles and Pittsburgh Pirates. He's written for ESPN, Fox Sports and Baseball Prospectus. Follow him on twitter.

I think it’s instructive to think about what would happen if a team like the Rays or Reds (or White Sox) who have multiple FV60+ prospects signed them all to extensions like this before they hit the majors. I think it’s pretty clear they would be coming out way, way ahead; even if we figure Moncada (who would have been signed for a lot more!) is stuck being a 2-win player forever, the value they signed away in that deal would likely be outpaced by the value they got from Kopech and Eloy. These are very team-friendly deals.

Kiley mentions the service time manipulation, and that definitely played a role in him signing a deal that is team-friendly. But it’s also the low pre-arb salaries. Just think of the world where, say, a player on the 40-man roster but in the minors earned what the minimum salary is now, and a pre-arb player earned 1.5M instead of the $500K or so they get now. Aside from directly raising the cost of buying out his pre-arb/arb years, Eloy would be in a much stronger bargaining position if he wanted to sign an extension like this.

This deal is not that team-friendly. The second-to-last paragraph explains why.

And in my opinion that risk is significant. I’ve seen Eloy in person several times over the last two seasons and on each occasion I came away thinking that he wasn’t going to stay in the outfield very long as a major leaguer.

That’s not true, the deal is slightly team friendly for ChiSox (its not zero sum necessarily). Slight surplus value plus some certainty, thats better than the alternative.

Very real DH-only, power-bat only concerns- but that’s baked into the projections, with ChiSox still getting a bit of surplus value. Jiminez is worth slightly more on the trade market under this contract than under his last, simply due to the definition of surplus value.

Correcting wage issues in MLB is pretty simple- pay the poorest more. Its crisis level when so many staff are unpaid and so many players dont make a living wage or a minimum wage.

Most of the effort to pay more to the non poorest will actually cripple the efforts to pay the poorest more. So for example, your suggestion to raise the pay for pre-arb players would (1) help 8-figure millionaires (now) like Jiminez make more, but (2) would cause many lesser compensated players to make less.

How?

By pricing 0-1 WAR players out of their market early in their cost-controlled years. There are tons of 0-1 WAR players, generally the 20th-40th best players in the organizations, who would lose their jobs to ‘major league minimum’ players if their pre-arb prices rose to 1.5m. Further, if their service time cemented their minimum wage at 1.5m for all clubs, there would be a ton of 25 year old ~1 WAR players who would be out of the game. The key point here is that the low price of the least compensated players (i.e. MLB minimum) would undermine the attempt to increase pre-arb compensation (since the minimum paid players would just get the jobs instead).

Raising minimums is the way to fix compensation issues, all other attempts will just exacerbate the divide.