Ichiro, Boz, and a Whirlwind Hall of Fame Induction Weekend

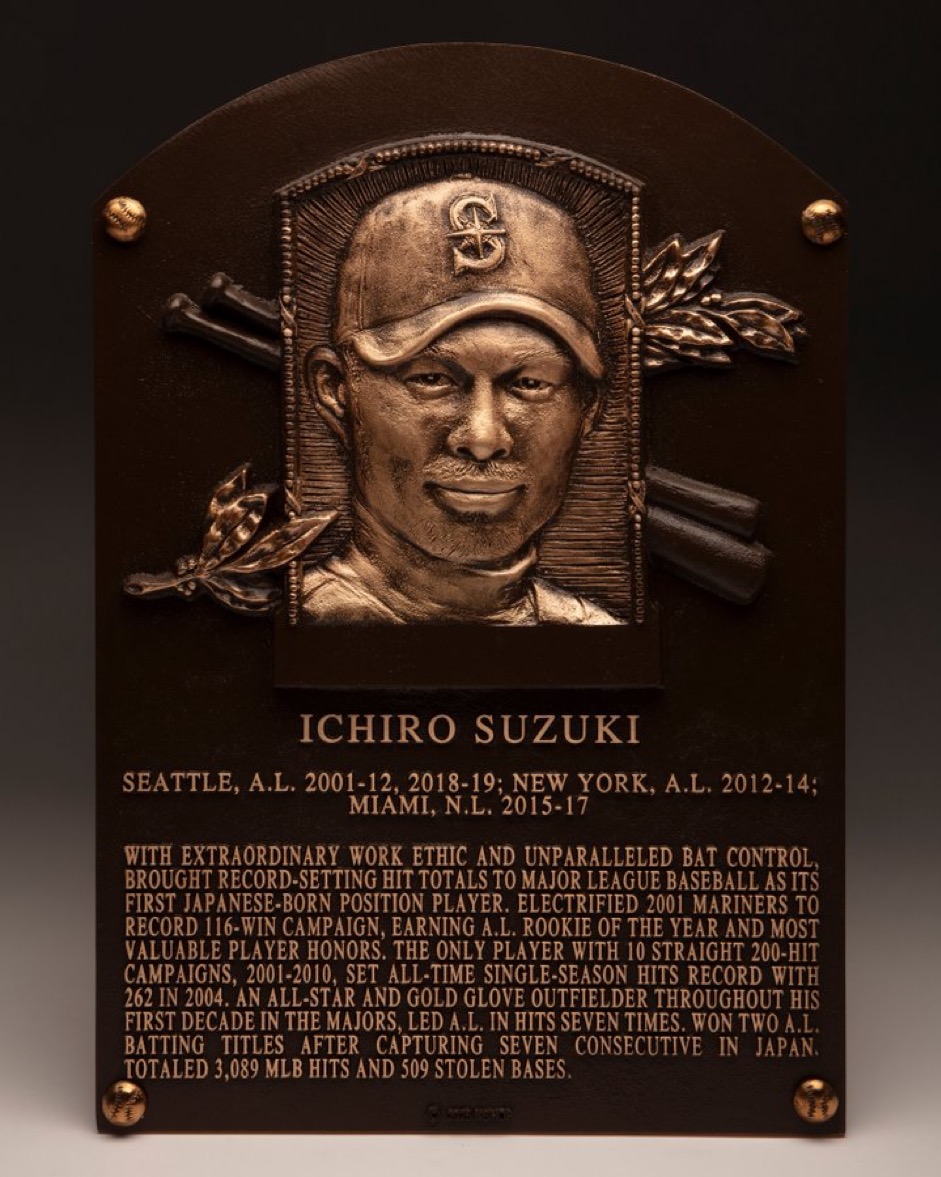

COOPERSTOWN, NY — During his 19-year major league career, Ichiro Suzuki rarely spoke English in public unless it was to express his thoughts about the temperature in Kansas City in August as it pertained to certain rodents. On Sunday in Cooperstown, however, he flawlessly delivered his 19-minute Hall of Fame induction speech in his second language, showing off his sly sense of humor while speaking about the professionalism, respect, and love for the fans that drove his career. “Today, I am feeling something I thought I would never feel again. I am a rookie,” he began, referring to his first seasons with the Orix Blue Wave in 1992 and the Seattle Mariners in 2001. “But please, I am 51 years old now. Easy on the hazing. I don’t need to wear a Hooters uniform again,” he quipped to the 52 returning Hall of Famers, four fellow entrants in the Class of 2025, and the estimated 30,000 people who attended the ceremony at the Clark Sports Center.

“The first two times, it was easier to manage my emotions because my goal was always clear: to play professionally at the highest level,” continued Suzuki. “This time is so different, because I could never imagine as a kid in Japan that my play would lead me to a sacred baseball land that I didn’t even know was here. People often measure me by my records: 3,000 hits, 10 gold gloves, 10 seasons of 200 hits. Not bad, eh?

“But the truth is, without baseball, you would say this guy is such a dumbass. I have bad teammates, right, Bob Costas?”

Elsewhere, Suzuki poked fun at having fallen one vote short of becoming just the second Hall candidate elected unanimously: “Three thousand hits or 262 hits in one season are achievements recognized by the writers. Well… all but one. And by the way, the offer for that writer to have dinner at my home has now expired.” On a more serious note, he advised distinguishing between dreams and goals: “Dreams are not always realistic, but goals can be possible if you think deeply about how to reach them. Dreaming is fun, but goals are difficult and challenging… If you are serious about it, you must think critically about what is necessary to achieve it.”

Near the end of his speech, Suzuki drew more laughs relaying an anecdote about being approached by Marlins president David Samson and general manager Mike Hill, who signed him in January 2015. “When you guys called to offer me a contract for 2015, I had never heard of your team,” he said.

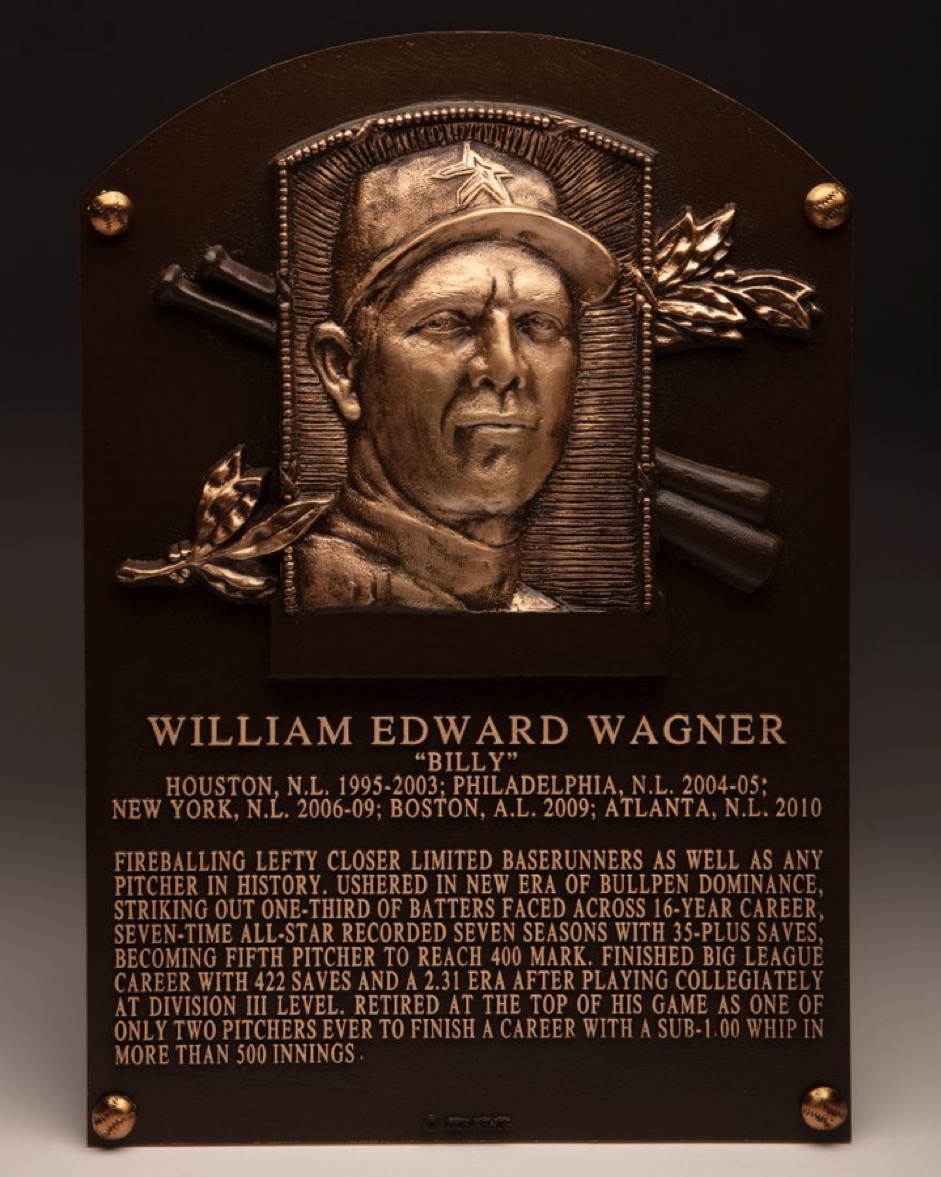

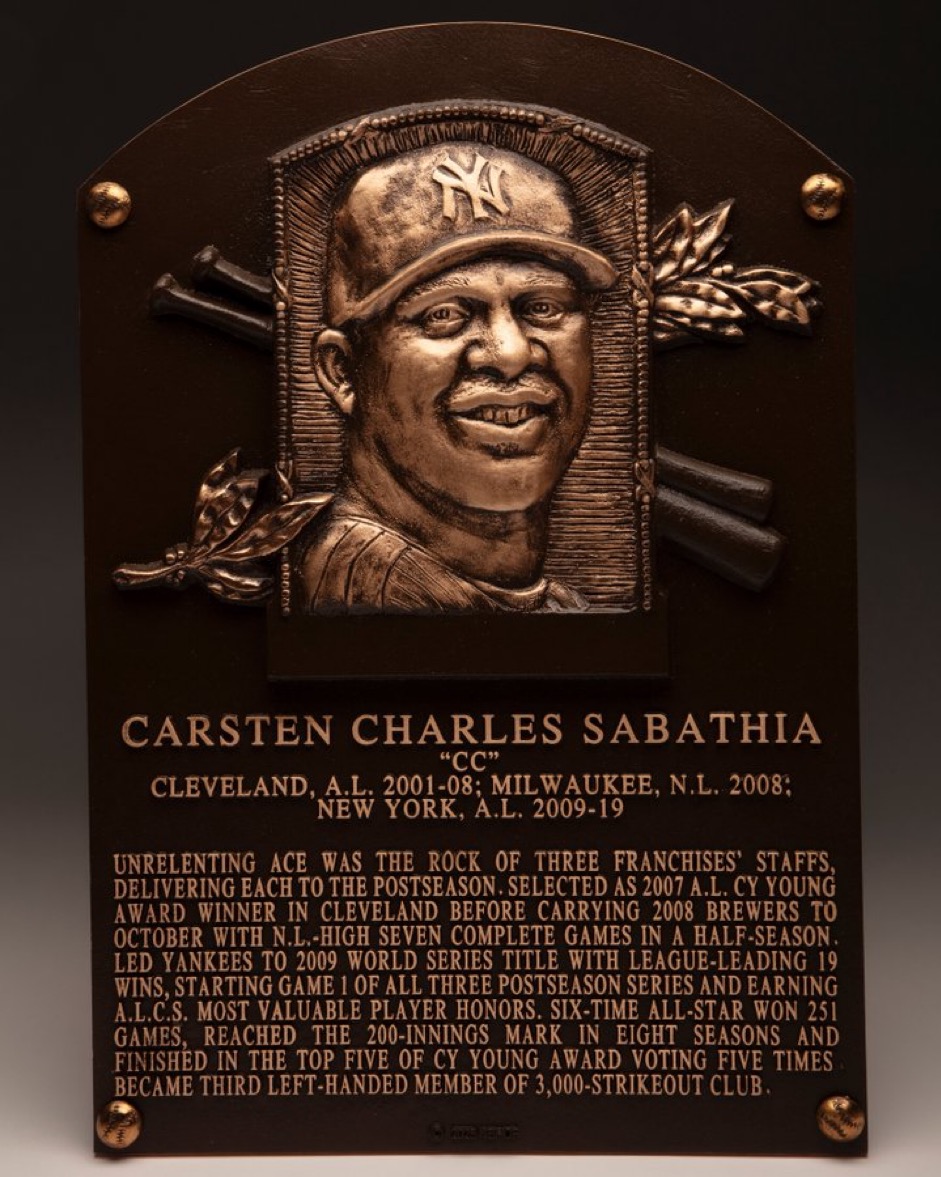

Suzuki’s speech was one for the ages, capping a three-hour ceremony whose start was delayed for an hour by rain. Before him, Billy Wagner, David Parker II (son of the late Dave Parker), Willa Allen (widow of the late Dick Allen), and CC Sabathia delivered poignant and memorable speeches of their own while basking in the love from their families and friends as well as the appreciation of their fans.

Under more optimal circumstances, Sunday’s ceremony might well have drawn upwards of 50,000 attendees, enough to crack the top five or 10 by the Hall’s estimates, if not to approach the record of 82,000 set in 2007, when Tony Gwynn and Cal Ripken Jr. were inducted. The rain wasn’t heavy, but may have curbed the impulse of many within driving distance (particularly Yankees fans supporting Sabathia) to trek to Cooperstown for the day, and so even with a sizable contingent of Japanese and Japanese-American fans, turnout was smaller than many expected. To these eyes at least, Sunday’s crowd still appeared much fuller than the (cough) 28,000 that the Hall claimed attended last year’s ceremony.

But it’s the honorees that matter, and this year’s class absolutely brought it when it came to sharing stories about their careers, expressing their sentiments regarding the meaning of this moment, and showing gratitude towards those who helped them reach this pinnacle. While statistics and accomplishments get a player elected to the Hall, Induction Day offers the chance to display their character and humanity. In that regard, this was a particularly impressive bunch.

Induction Day capped a whirlwind weekend of Hall-related festivities, a week’s worth of social and cultural activity and revelry packed into a 48-hour stretch. While I’ve covered Hall elections in a professional capacity since 2004, and visited Cooperstown a dozen times, I’ve never shared an account of the full experience of Induction Weekend with readers, so at the behest of editor Meg Rowley, I’m doing so here.

For this scribe, the whirlwind began soon after pulling into the driveway of my host, former Cooperstown mayor/author Jeff Katz, and it kept my body and my cell phone in need of frequent recharging. This was my eighth induction, though that tally comes with an asterisk; my 2018 trip required a departure before the ceremony to accommodate trade deadline coverage, and the 2021 event was a muted midweek ceremony due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Each weekend carries a different vibe, as the selection of honorees factors into which fan bases (and media) make the pilgrimage to Cooperstown. One thing is for certain: Even the most grizzled writers in my orbit agreed that this never gets old.

For the writers who have reached the 10-year service mark that grants them a Hall of Fame ballot, Induction Weekend festivities kick off with a Friday evening cocktail party to celebrate the year’s BBWAA Career Achievement Award winner. In a tradition that began 30 years ago as the brainchild of BBWAA secretary/treasurer Jack O’Connell and then-Hall of Fame vice president (later president) Jeff Idelson, the party takes place on the back porch of the Hotel Otesaga, where new and returning Hall of Famers and their immediate families stay for the weekend. To walk through the Otesaga lobby is to play “Spot the Legend.” On your left is Rollie Fingers! To your right is Ozzie Smith, but don’t linger too long or you’ll miss Wade Boggs over there! A conspicuous sign warns, “NO AUTOGRAPHS” and if you ever hope to return to the hotel for this event, you will take that to heart.

The Otesaga’s back porch opens up onto a breathtaking vista starring Lake Otsego. It may not be an official wonder of the world on par with the Grand Canyon, but the magnificence of the setting signifies our own achievement for lasting long enough in this business to celebrate the best of our profession in style.

This year’s award went to Thomas Boswell, now (mostly) retired after a stellar 52-year run at the Washington Post, where he covered the Baltimore Orioles before becoming the national baseball writer for a city with no major league team until the Nationals arrived; he covered 252 consecutive World Series games, ending with the Nationals’ 2019 clincher. I’d never met Boswell, but I was particularly keen to do so. In 1998, my roommate — who worked at Criterion at the time — brought home Boswell’s first two collections of columns from the 1970s and ’80s, How Life Imitates the World Series and Why Time Begins on Opening Day. Now renowned for its high-end reissues of classic films, in its previous incarnation, Criterion had been a multimedia company called Voyager, whose 1994 CD-ROM called Baseball’s Greatest Hits incorporated passages from Boswell’s books. Stocked with stories about Earl Weaver and players I’d grown up watching, as well as earlier legends such as Sandy Koufax and Bill Veeck, the books rekindled my love of great baseball writing. Devouring them and immersing myself in following the powerhouse 1998 Yankees spurred my desire to write about the game, setting me on the path that led to my first blog and, eventually, a new career.

After a couple of beers and countless handshakes with fellow writers, I waited out Boswell as he posed for photographs holding a personalized bat from the Cooperstown Bat Company, then summoned the courage to introduce myself. I told him how I acquired those two books and what they meant to me, and he seemed genuinely touched. He shared a funny story about Weaver’s reaction to his creation of the proto-sabermetric stat Total Average in the late 1970s (“Branch Rickey did it better!” snapped Weaver, who nonetheless allowed that Boswell was onto something). Boswell also relayed that he’d read my work at FanGraphs and is a big fan of our fair site. Our five-minute conversation is one I’ll always cherish:

Saturday brought the first of two trips through the Hall itself, primarily to check out the new exhibit, “Yakyu Baseball: The Transpacific Exchange of the Game” — well-timed to capitalize on Suzuki’s induction and the current superstardom of Shohei Ohtani, but with over 150 years of history behind it. As part of my annual ritual, I had initially planned to spend about 90 minutes flying solo, but instead I accepted a request to take a baseball novice through the exhibit: Ruby, the 20-year-old daughter of a fellow houseguest. Her father Jimmy’s Induction Weekend ritual is to set up a tableful of baseball cards of Hall of Famers — most ranging from $1-$5, from a dizzying array of manufacturers (you can buy the more expensive ones at the shops on Main Street) — and hawk them to passers-by, so he needed a pinch-hitter.

Jimmy had given Ruby, who previously cared little about baseball, directives to visit the plaques of Babe Ruth, Jackie Robinson, Roberto Clemente, and Effa Manley. I escorted her through the Hall, explaining their significance, showing her some other key inductees (Willie Mays over here, Hank Aaron over there, Bud Fowler and “My Guys” — candidates for whom I’d advocated such as Edgar Martinez, Minnie Miñoso, and Scott Rolen — in this corner). We then breezed through the museum, visiting artwork on the first floor (Norman Rockwell, LeRoy Nieman, and my Brooklyn neighbor Graig Kreindler) and the sepia-toned early baseball exhibits on the second, before stepping into the brighter colors of the more recent exhibits. “The Souls of the Game: Voices of Black Baseball,” and “Diamond Dreams: Women in Baseball” did a better job of holding our attention, as did the baseball card exhibit “Shoebox Treasures,” where Ruby gawked at a replica of the Honus Wagner T-206 that sells for millions of dollars.

The bilingual Yakyu exhibit was quite crowded, full of inviting interactive exhibits that engaged children as well as adults. A larger-than-life lenticular photo of Othani, showing him as a pitcher for the Angels, and a hitter for the Dodgers and Samurai Japan, depending upon the angle, transfixed me, but what really captivated Ruby was the video of Hideo Nomo’s distinctive corkscrew delivery; later that afternoon, she asked her father for a Nomo card to start her “collection.” We left the museum after she procured postcards of the plaques we’d visited; for my part, I bought an officially licensed reproduction of Parker’s iconic “Boppin” t-shirt. I could write a whole column on the tour, but suffice it to say that I hope someday I’m able to give my own daughter a similar one, and likewise that Jimmy and Ruby get to do it their way together.

I missed Saturday afternoon’s awards ceremony for Boswell and Ford C. Frick Award winner Tom Hamilton, the longtime broadcaster for the Cleveland Guardians. The ceremony takes place on the other side of Lake Otsego — a car ride, shuttle bus and world away from the action on Main Street, where I instead opted for a more private annual ritual, meeting loyal reader Chris Pesqueira, who over the last seven years has purchased more than a dozen copies of The Cooperstown Casebook as gifts, for a beer and a signing session. (Pat and Paul, I hope you both enjoy your Casebooks!) Boswell’s speech, which I caught later, was as eloquent as expected. “Earl Weaver was my grad school professor,” he said of his ongoing quest to learn more about the game:

Saturday evening brought another tentpole event: a cocktail party in the Hall of Fame plaque gallery following the Parade of Legends, for which the returning Hall of Famers ride a few blocks down Main Street, in order of the year they were inducted, from the earliest to the most recent. While the 89-year-old Koufax attended Induction Day for the first time since 2022 (the 50th anniversary of his own induction), he did not ride in the parade; instead 87-year-old Juan Marichal from the Class of 1983 led the way, followed by Billy Williams (1987) and Johnny Bench (1989). At the plaque party, Jeff and I lamented the dwindling number of living pre-1990s inductees; research tells me 91-year-old Luis Aparicio (1984) and 85-year-old Carl Yastrzemski are the only others not previously mentioned.

To attend a plaque party is to visit baseball nirvana, albeit one where career immortality and physical mortality clash in sometimes jarring fashion. At my first plaque party in 2019, I spotted a table where Bench, Joe Morgan, George Brett and Rod Carew held court in the general vicinity of their bronze plaques. The legends of my childhood were suddenly Topps All-Stars who had not only come to life, but were confronting their own brushes with mortality; Carew had been a recent recipient of a heart transplant, and Morgan was frail and in need of crutches due to his neuropathy.

This year, I reintroduced myself to Robin Yount, a boyhood favorite of mine, whom I’d met two years ago (at that time, statistician Steve Hirdt asked him a trivia question to which Eddie Murray, who was standing right next to him, was the answer), and Jim Thome, a more recent favorite. The latter, in addition to walloping 612 homers (eighth all-time), holds the distinction of being the first Hall of Famer to compliment my work on MLB Network and to suggest that we appear together on MLB Now (your move, Brian Kenny). At a buffet of cold cuts, cheese cubes, and crackers, another former player made small talk while filling his plate.

“I’m gonna makes some Lunchables. You remember Lunchables, right?” he asked me, displaying his neatly-layered cracker.

“Of course,” I reply. “I’ve got an eight-year-old who loves them.” We did not exchange introductions, though I wish we had: It was Adam Jones, five-time All-Star and four-time Gold Glove winner. Other sightings included Pedro Martinez bowing to Suzuki and exchanging hugs in the lobby; a solitary Carew perusing the Hall gift shop; Eric Davis (who was mentored by Parker) in gym shorts but still turning the heads of men of a certain age in awe of his power-speed combination; and Dave Winfield looking impossibly tall, Randy Johnson even taller. I wanted to ask the latter about the Ozzy Osbourne photo I’d recently re-shared on Bluesky, but that opening never came. Wait ’til next year!

Two encounters came to fruition in memorable fashion, including one that brought closure to a story I told in my 2020 Morgan tribute. In 2019, Seattle Times columnist Larry Stone helped me set up an interview with Edgar Martinez, with whom he’d just done a book to coincide with the Mariner great’s induction. I asked Larry for an introduction to Martinez, a favorite of my late uncle (who in his retirement worked as an usher at Safeco Field’s Diamond Club) and one of my older cousins. In search of Martinez, I’d hurriedly tried to weave through the crowd to the Hall lobby before coming to a screeching halt while Morgan was slowly helped along a few feet in front of me. At that point I confronted my own baseball mortality with a vision of the outcry that would have ensued if this longtime critic accidentally knocked over the ailing legend (thankfully, no contact ensued).

This time, I found Martinez taking photographs with Ken Griffey Jr. I waited them out until after Griffey moved away, then introduced myself, reminding Martinez of our interview and telling him about my uncle and the Morgan near-miss. He enjoyed the tale and posed for a photo. Next year maybe I’ll chase down Junior:

Just before exiting the Hall to return to the Katz house for a private porch party of about a dozen people (including old friends Bill Francis, a Hall of Fame researcher, and Todd Radom, a graphic designer who’s worked with Major League Baseball for decades), I spotted Wagner also preparing to depart. Knowing that he’s the rare Hall candidate to follow me on Twitter (Tim Raines is the only other one I can recall), I introduced myself and told him how glad I was he’d finally been elected. He thanked me for my advocacy, and we took a selfie:

On Sunday, Wagner remarked that he never started a single game in the majors. In the post-ceremony media availability session, he joked about leading off the day’s ceremony. “Everybody wanted that spot, but I’ve waited the longest [of those elected by the writers]. It was good to get that out of the way. The longer I’d have waited, the more emotional I probably would have gotten, so I think they said, ‘Let’s get that guy off the stage as quick as possible.'”

“They kept shooting the over/under on me,” said Wagner of the high school players he coaches and the family members in the audience, who were guessing the number of times he’d break down while delivering his speech. “My Miller [High School] kids are out there, and I’m seeing five breakdowns. My own kids are sitting there going, ‘We got you at three [breakdowns].’ I held it together enough that they all lost.”

Wagner overcame a childhood of poverty and back-to-back fractures of his right (dominant) arm at age seven, which led him to learn to throw left-handed. Thanks to his lower body strength, the 5-foot-10 southpaw could still dial his fastball up to 100 mph into the final year of his career (2010), and in his 10th and final year of BBWAA eligibility became the first lefty reliever (and first Division III player) elected to the Hall. Near the end of his speech proper, Wagner offered an inspiring message “to every kid out there”:

Obstacles are not a road block. Obstacles are stepping stones. They build you and shape you, refine you. I wasn’t the biggest, I wasn’t left-handed. I wasn’t supposed to be here. There were only seven full-time relievers in the Hall of Fame. Now, there are eight because I refused to give up, or give in. I refused to listen to the outside critics, and I never stopped working.

“That’s what this game does for you: It teaches you about life, it teaches you how to persevere,” he continued. “Don’t fear failure. Embrace it, because perseverance isn’t just a trait, it’s a path to greatness.”

(All plaque photos are courtesy of the Hall of Fame’s Twitter feed)

Next up was the younger Parker, the spitting image of his father, who passed away on June 28 due to complications from Parkinson’s Disease, which he was diagnosed with in 2012. The elder Parker at least lived long enough to learn that he’d been elected, and to experience the accompanying outpouring of joy after 15 rounds of disappointment on the writers ballot and three previous Era Committee ballot appearances. In the months before dying, he helped craft the speech his son delivered, and for anyone who has read the 2021 autobiography Cobra: A Life of Baseball and Brotherhood that he wrote with Dave Jordan, it felt true to his voice. The younger Parker told stories of his father starring as a Pittsburgh Pirate before retuning home to Cincinnati to fulfill his childhood dream of starring for the Reds as well. The speech concluded with a poem by the elder Parker that alluded to many of his career highlights:

Here I am, 39.

About damn time.

I know I had to wait a little,

but that’s what you do with fine aged wine.

I’m a Pirate for life.

Wouldn’t have it no other way.

That was my family,

even though I didn’t go on Parade Day.

I love y’all, the Bucs on my heart

because those two championships I got,

y’all played in the first part.

I’m in the Hall now,

you can’t take that away.

That statue better look good —

you know I got a pretty face.

Top-tier athlete,

fashion icon,

sex symbol.

No reason to list the rest of my credentials.

I’m him, period.

The Cobra.

Known for my rocket arm,

and I will run any catcher over.

To my friends, families: I love y’all.

Thanks for staying by my side.

I told y’all Cooperstown would be my last ride.

So the Star of David will be in the sky tonight.

Watch it glow.

But I didn’t lie on my documentary:

I told you I wouldn’t show.

Those last lines made the hair on my neck stand up. In crafting my tribute last month, I had rewatched MLB Network’s documentary The Cobra at Twilight. I considered including his comment about induction — “I might not show up” — which harkened back to his skipping the Pirates 1979 World Series parade after a season that wore on him mentally. I ultimately left it on the cutting room floor because it felt too on-the-nose, but apparently, it was exactly what the man wanted to say.

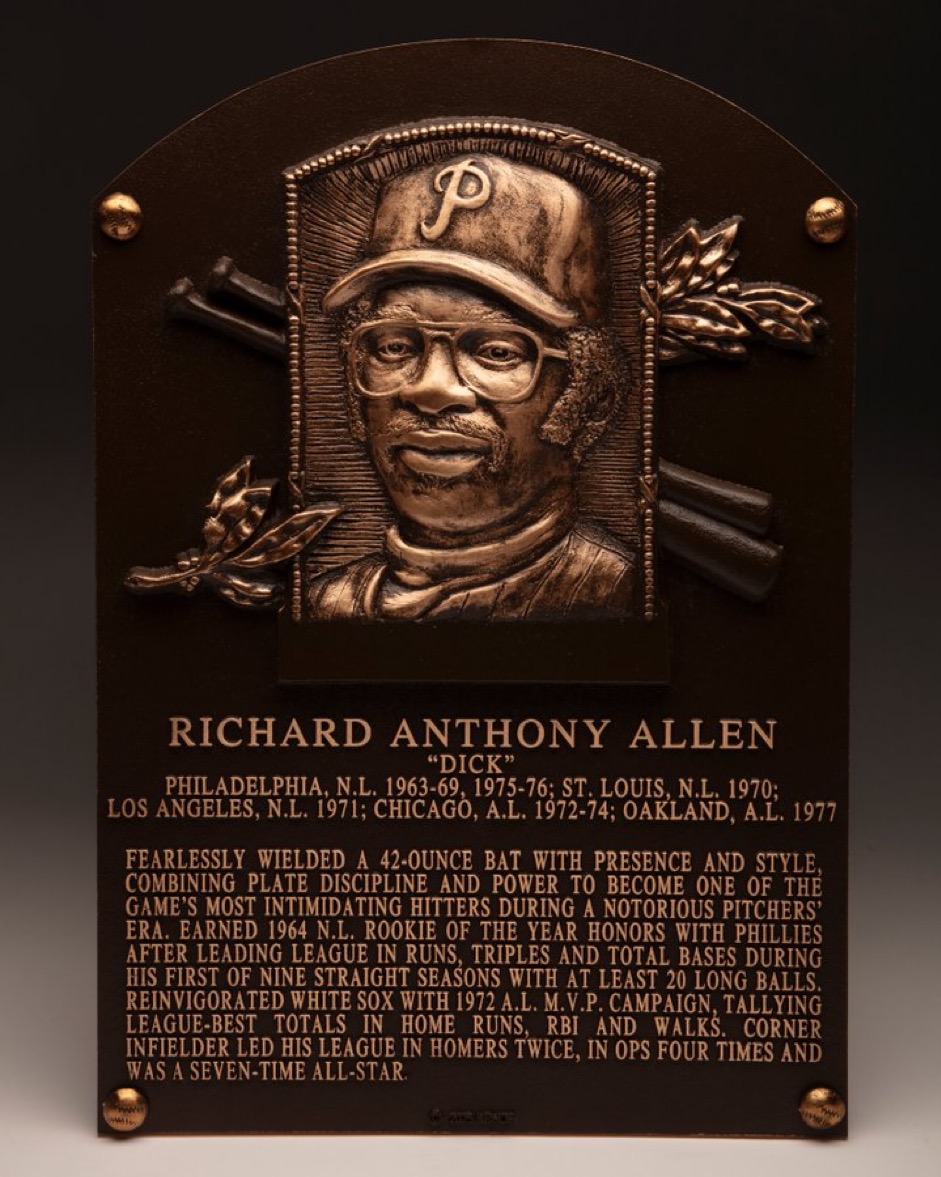

Allen, who died of cancer on December 7, 2020 at age 78, did not have the luxury of fashioning his own send-off or of knowing he’d been elected. He fell one vote short on the 2015 Golden Era Committee and 2022 Golden Days Era Committee ballots, the latter of which had been postponed by a year due to the pandemic, which prevented the panel from meeting in person. However, Allen received some acknowledgement and closure before his death when Phillies owner John Middleton reversed the franchise’s longstanding policy by retiring Allen’s no. 15 — an honor that had previously been limited to Hall of Famers — in September 2020 at Citizens Bank Park. As Willa Allen, his wife of 33 years, told it, her husband was too ill even then to deliver the full speech he had composed. Instead he “spoke from the heart” with a shorter acceptance that day.

“They knew, as we did, that Dick’s legacy transcended technicalities,” said Willa Allen on Sunday. “That day in Philadelphia meant everything to him, and to our family. It was a moment we’ll never forget. To see Dick recognized in that way while he was still alive, to feel the love from Philadelphia — the organization and the fans — that was a gift.”

Her speech packed an emotional punch the equal of the young Parker’s. “To many of us, Dick was already a Hall of Famer. Not just for how he played, but for who he was. Yes, he was one of the most natural, gifted hitters to ever step into the batter’s box. And who could forget his 40-ounce bat? But his statistics, impressive as they are, tell only part of his story. And I have hundreds of stories.”

She told one of Allen growing up in tiny, mostly-white Wampum, Pennsylvania (he was one of just five Black students in a high school class of 146). At a young age, he envisioned his future: “When he was just a child, his teacher asked the class what they wanted to be when they grew up. Dick stood up and said, ‘I’m going to be a major league baseball player.’ Then he sat down. The other kids laughed because at that time, there weren’t any Black players in the major leagues. But he didn’t laugh. He believed it, and now, look at him.”

Allen, who signed with the Phillies in 1960, was often at odds with the world around him, an experience shaped by the team and the city both being far behind the integration curve. The Phillies were the last of the eight National League teams to integrate, not doing so until April 22, 1957, 10 years after Jackie Robinson debuted with the Dodgers. Allen experienced racism in the minors even before the team assigned him to its Triple-A affiliate in Little Rock in 1963, where he not only became the first Black professional baseball player in the state of Arkansas, but also was subjected to watching Governor Orval Faubus, infamous for his role in resisting desegregation, throw out the first pitch on the night of his debut. Some white fans picketed the game, carrying signs with slogans such as “Don’t Negro-ize baseball” and “N***** go home.” One left threats on his car (“DON’T COME BACK AGAIN N*****”). Death threats and Jim Crow laws were reminders he was rarely safe.

In the four-minute introductory video before Willa Allen’s speech, former teammate Mike Schmidt — who played with Allen when he returned to the Phillies in 1975 and ’76 — addressed the team’s mishandling of him. “I knew that Dick had a real tough time with the Philly fans and the city of Philadelphia. Philly was one of the last teams to have a Black player in the major leagues. I can’t imagine how good Dick Allen would have been in those days if he had been accepted. I think he would have been a greater baseball player, a greater athlete, if it weren’t for that.”

Willa Allen’s speech showed the softer side of her husband. “He loved the game,” she said. “But more than that, he loved the people in it. Baseball was his first love. He used to say, ‘I’d have played for nothing,’ and I believe he meant it. But of course, if you compare today’s salaries, he played almost for nothing.”

As Sunday’s ceremony neared the two-and-a-half hour mark, Sabathia delivered a speech that was mercifully succinct, centered around family and particularly the “village of women who raised me, guided me, made me laugh, protected me and a few times literally saved me.” In the hyper-masculine world of the major leagues, and a setting where all but one of the 351 enshrinees are men (Manley being the exception), Sabathia’s speech offered a refreshing point of view, not that the other honorees didn’t thank their mothers and wives. Sabathia recalled throwing grapefruits in his maternal grandmother Ethel’s backyard in Vallejo, California; later she would counsel him to forgo a summer job to focus on baseball. His mother Margie, a former fast-pitch softball player, would don protective gear to catch his fastball, and talk pitch selection; she also took him to A’s games at the Oakland Coliseum. “My mom is the reason I’m a baseball fan. And fans turn into players who sometimes turn into Hall of Famers,” said Sabathia. As for his wife Amber, “I know I’m super difficult to be around sometimes. She knows how to navigate me like no one else does.”

Sabathia also expressed concern about the dwindling number of Black players within baseball. “I don’t want to be the final member of the Black Aces,” he said, referring to the fraternity of 15 Black pitchers who won 20 games in an AL or NL season. “I don’t want to be the final Black pitcher to be giving a Hall of Fame speech.” In his post-ceremony availability, he added, “I think it’s on me and my generation to find that next [Black Ace] through the Players Alliance and the work that we’re doing.”

Finally it was time for Ichiro’s speech. From where I sat in the audience in Section 3, I was surrounded by fans in Mariners jerseys, nearly all of them representing Ichiro’s no. 51. As we’ve seen for the inductions of Griffey in 2019 and Martinez three years later, Mariners fans travel particularly well when given the chance to honor their heroes. The speech turned out to be an all-timer, as distinctive and unique as the wiry and wily hit machine who collected a total of 4,367 hits at the highest level of play on two continents. And with that, another memorable Hall of Fame weekend, unique in its own right, passed into the books.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

Brilliant long-form article in the tradition of old. A thoroughly enjoyable read.