Envelope Please: The 2025 Crowdsourced Trade Value Results

Two weeks ago, we launched our new crowdsourced trade value tool, which aggregated responses to simple “Which of these two players do you prefer?” questions to create a composite trade value ranking across our readership. With your help, we logged nearly 900,000 matchups – 897,035, to be precise. Now that the Trade Value Series is in the books, it’s time to see how the broader FanGraphs audience lined everyone up. Today, I’ll walk you through how to access and interpret your results, which can be found here, and share a few interesting tidbits about the places where the crowd and I agreed or differed.

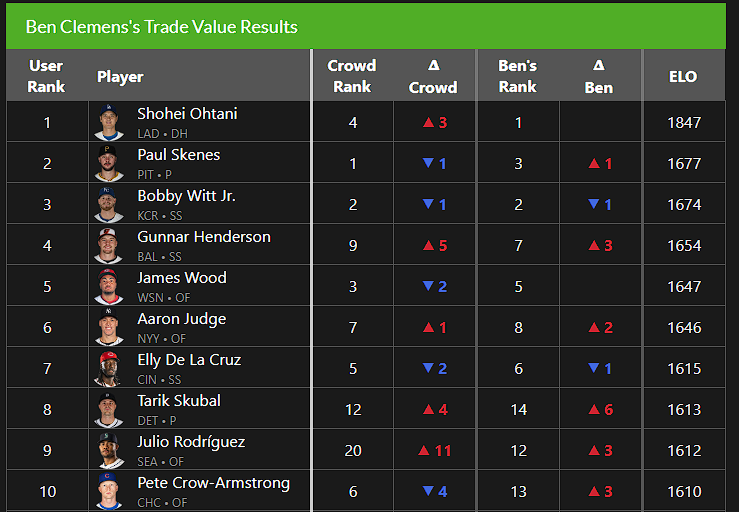

Let’s start with the exercise itself. We sampled up to 500 results from each user’s set of submissions and threw them all into one big group of matchups. We ordered those matchups randomly, then used Elo ratings to turn the matchups into an ordered list. Then we redid the random ordering a total of 100 times and averaged the results, which got rid of Elo’s bias towards more recent matchups. That created a list of the crowd’s aggregate preferences. When you open the above link, the first thing you’ll see is your own results in full. I, for example, came pretty close to matching my official list: