2023 Contemporary Baseball Era Committee Candidates: Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, and Curt Schilling

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the 2023 Contemporary Baseball Era Committee ballot. For a detailed introduction to this year’s ballot, use the tool above. An introduction to JAWS can be found here.

Content warning: This piece, and the original pieces to which it links, contains details about alleged domestic violence and sexual impropriety. The content may be difficult to read and emotionally upsetting.

The Baseball Writers Association of America may be done with these guys, but the Hall of Fame isn’t… yet. Eleven years ago, one of the most talented classes of first-year candidates landed on the writers’ ballot. From a group that included Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens and Curt Schilling, not to mention Craig Biggio, Kenny Lofton, Mike Piazza, and Sammy Sosa — as well as four holdover candidates subsequently elected by the writers, and three chosen by the Era Committees — the writers elected no one, pitching their first shutout in 17 years. Voting hasn’t been the same since. While Biggio and Piazza were eventually elected by the writers, the quartet of Bonds, Clemens, Schilling, and Sosa were not. Their continued presence on the ballot, and the rancorous debate that surrounded their candidacies, at times gummed up the process, diverting attention away from other compelling candidates and souring many participants and observers on the entire endeavor, if not the institution itself. The politics of glory, indeed.

The polarizing public debate surrounding candidates linked to performance-enhancing drugs — a group that at the time included not just Bonds, Clemens, and Sosa but also Mark McGwire and Rafael Palmeiro — led the Hall’s board of directors to change the rules mid-candidacy by reducing players’ windows of eligibility from 15 years to 10. Where Hall president Jeff Idelson said in 2011 with regards to PED-linked candidates, “[W]e’re happy with the diligence of the voters who have participated, and the chips will fall as they fall,” once it became apparent that Bonds and Clemens were trending towards election, the institution put its thumb on the scale via board member Joe Morgan’s open plea for voters not to consider steroid users. Morgan’s letter conveniently sidestepped the likelihood that some steroid users — and numerous known users of another performance-enhancing drug, amphetamines — had already been elected.

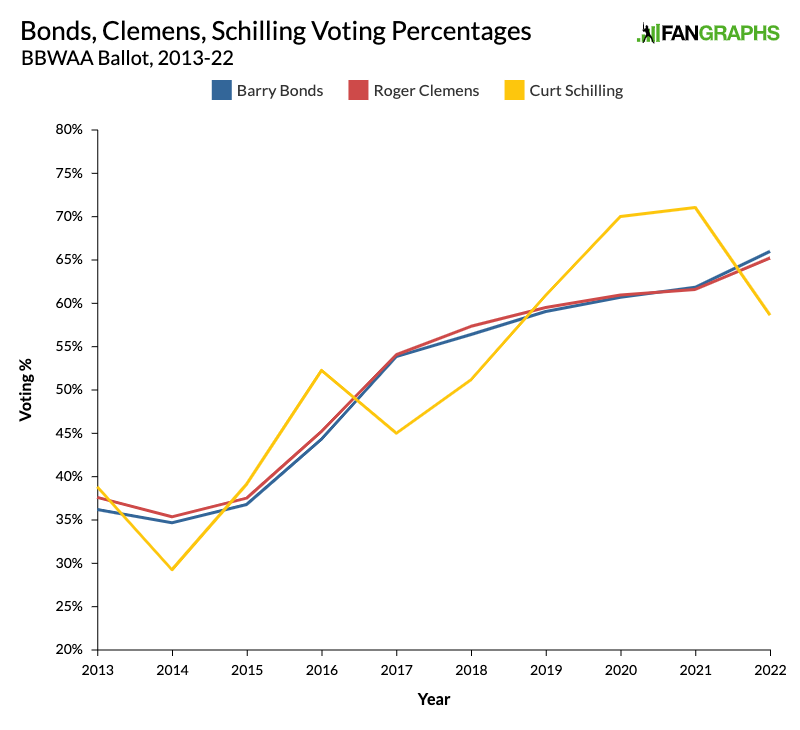

Voters who had already given the so-called “character clause” a thorough workout once McGwire and Palmeiro gained eligibility further contorted themselves to rationalize not voting for Bonds or Clemens, players whom they and their peers had previously honored via seven MVP awards (Bonds) and seven Cy Young awards (Clemens) even while they were putting up astronomical numbers. While Bonds and Clemens were linked to PEDs through extensive reporting, neither was ever suspended by Major League Baseball, for their infractions took place before any kind of enforcement mechanism was in place; still, some subset of Hall voters decided that a measure of frontier justice was appropriate. In January of this year, their candidacies before the writers expired, with Bonds (66%), Clemens (65.2%), and Sosa (18.5%) all receiving their highest shares to date but still falling short, the last of those merely an afterthought even as the ballot traffic thinned. As for Schilling, who has never been linked to PED use, he plummeted to 58.6% while inventing unprecedented ways to sabotage his own Hall of Fame candidacy and bring questions of character to the foreground.

Just as the quartet’s wearying decade on the writers’ ballot ended, the Hall changed the rules again, this time introducing a minimum one-year waiting period between a candidate’s appearances on that ballot and the Era Committee one. The Hall did grandfather the “graduates” of the 2022 ballot, however, and with BBWAA ballot performance clearly part of the consideration when it came to crafting the new Contemporary Baseball ballot — no one-and-done candidates such as Lofton or Lou Whitaker were included, and only three of eight who peaked in the 5%-25% range — Bonds, Clemens, and Schilling are here, but not Sosa.

Last year, in an effort to condense our publishing schedule — which was crowded by a double dose of Era Committee profiles — and to minimize the extent to which I relitigated the same arguments I had made for a decade, I dispensed with my annual renewal of these profiles. I am continuing that approach this year, instead using this post as a clearinghouse to link to and excerpt the 2021 editions; to update the candidates’ stats as they pertain to the relevant JAWS standards (which have shifted slightly with last year’s Era Committee voting and my introduction of the experimental, workload-adjusted Starting Pitcher JAWS, or S-JAWS); to summarize their voting trends; and to round up anything else we’ve learned since the last time I ran these profiles. All three are strong candidates based on the numbers, but as for everything that surrounds the numbers, well, that’s the reason they’re here and not already enshrined.

Roger Clemens (65.2% on 2022 ballot)

| Pitcher | Career WAR | Peak WAR Adj. | S-JAWS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roger Clemens | 139.2 | 64.0 | 101.6 |

| Avg. HOF SP | 73.3 | 40.7 | 56.8 |

| W-L | SO | ERA | ERA+ |

| 354-184 | 4,672 | 3.12 | 143 |

From the intro:

Roger Clemens has a reasonable claim as the greatest pitcher of all time. Cy Young, Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson, and Grover Cleveland Alexander spent all or most of their careers in the dead-ball era, before the home run was a real threat, and pitched while the color line was still in effect, barring some of the game’s most talented players from participating. Sandy Koufax and Tom Seaver pitched when scoring levels were much lower and pitchers held a greater advantage. Koufax and 2015 inductees Randy Johnson and Pedro Martinez didn’t sustain their greatness for nearly as long. Greg Maddux didn’t dominate hitters to nearly the same extent.

Clemens, meanwhile, spent 24 years in the majors and racked up a record seven Cy Young awards, not to mention an MVP award. He won 354 games, led his leagues in the Triple Crown categories (wins, strikeouts, and ERA) a total of 16 times, and helped his teams to six pennants and a pair of world championships.

Alas, whatever claim “The Rocket” may have on such an exalted title is clouded by suspicions that he used performance-enhancing drugs. When those suspicions came to light in the Mitchell Report in 2007, Clemens took the otherwise unprecedented step of challenging the findings during a Congressional hearing, but nearly painted himself into a legal corner; he was subject to a high-profile trial for six counts of perjury, obstruction of justice, and making false statements to Congress. After a mistrial in 2011, he was acquitted on all counts the following year. But despite the verdicts, the specter of PEDs hasn’t left Clemens’ case, even given that in March 2015, he settled the defamation lawsuit filed by former personal trainer Brian McNamee for an unspecified amount.

More here.

Barry Bonds (66% on 2022 ballot)

| Player | Career WAR | Peak WAR | JAWS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barry Bonds | 162.8 | 72.7 | 117.8 |

| Avg. HOF LF | 65.2 | 41.6 | 53.4 |

| H | HR | AVG/OBP/SLG | OPS+ |

| 2,935 | 762 | .298/.444/.607 | 182 |

From the intro:

If Roger Clemens has a reasonable claim as the greatest pitcher of all time, then the same goes for Barry Bonds as the greatest position player. Babe Ruth played in a time before integration, and Ted Williams bridged the pre- and post-integration eras, but while both were dominant at the plate, neither was much to write home about on the base paths or in the field. Bonds’ godfather, Willie Mays, was a big plus in both of those areas, but he didn’t dominate opposing pitchers to the same extent. Bonds used his blend of speed, power, and surgical precision in the strike zone to outdo them all. He set the single-season home run record with 73 in 2001 and the all-time home run record with 762, reached base more often than any player this side of Pete Rose, and won a record seven MVP awards along the way.

Despite his claim to greatness, Bonds may have inspired more fear and loathing than any ballplayer in modern history. Fear because opposing pitchers and managers simply refused to engage him at his peak, intentionally walking him a record 688 times — once with the bases loaded — and giving him a free pass a total of 2,558 times, also a record. Loathing because even as a young player, he rubbed teammates and media members the wrong way (occasionally, even his manager) and approached the game with a chip on his shoulder because of the way his father, three-time All-Star Bobby Bonds, had been driven from the game due to alcoholism. The younger Bonds had his own issues off the field, as allegations of physical and verbal abuse of his domestic partners surfaced during his career.

As he aged, media and fans turned against Bonds once evidence — most of it illegally leaked to the press by anonymous sources — mounted that he had used performance-enhancing drugs during the latter part of his career. With his name in the headlines more regarding his legal situation than his on-field exploits, his pursuit and eclipse of Hank Aaron’s 33-year-old home run record turned into a joyless drag, and he disappeared from the majors soon after breaking the record in 2007 despite ranking among the game’s most dangerous hitters even at age 43.

More here.

From an electoral standpoint, Bonds and Clemens were close to inseparable. Only in their debut were they more than a point apart, and so they’re more easily lumped together as the Gruesome Twosome. Their candidacies started slowly but began to pick up steam starting with the 2016 ballot, once voters more than 10 years removed from active coverage were scrubbed from the electorate. Those older voters, who were less likely to publish their ballots publicly, tended to have a more hardline stance when it came to PED users, and so their elimination — which appears to have peeled off more than 100 “no” votes but few “yes” votes — paved the way for significant gains in voting shares. The pair gained further momentum following the 2017 Today’s Game election of commissioner Bud Selig, who presided over the so-called “Steroid Era” and who additionally had sullied his own candidacy by participating in the owners’ mid-1980s collusion scandal. “Senseless to keep steroid guys out when the enablers are in Hall of Fame,” tweeted Susan Slusser, a past BBWAA president then serving as the Oakland A’s beat writer for the San Francisco Chronicle. “I now will hold my nose and vote for players I believe cheated.”

The Morgan letter, published in November 2017, stopped the pair in their tracks; over their last five cycles, Bonds gained just 12.1%, Clemens 11.2%. While first-time voters supported them at about an 87% clip, few returnees flipped their votes. The opposition had become too entrenched for either to overcome, and it didn’t help that the increased focus on character issues beyond PEDs — for which they can thank not only Schilling but also the 2015 introduction of MLB’s domestic violence policy — brought renewed focus to old allegations concerning their behavior towards women. During Bonds’ 1995 divorce trial, his first wife, Sue Bonds, alleged at least five episodes of spousal abuse dating as far back as ’88, while during his 2011 perjury trial, his longtime girlfriend-turned-ex Kimberly Bell alleged that she had been the recipient of his repeated verbal abuse and threats of violence. As for Clemens, in 2008 the New York Daily News reported that that he carried out “a long-term affair” with country singer Mindy McCready that dated back to when the pitcher was 28 years old and the singer just 15, making her below the age of consent in both parties’ home states as well as Florida, where they met. Clemens denied that the relationship was sexual, and in November 2008, McCready told Inside Edition that they met when she was 16, and that the relationship didn’t turn sexual until “several years later.” As best I can tell, only one voter, ESPN’s Christina Karhl, publicly cited such issues while withdrawing support (in her case, just for Clemens), but the recirculation of allegations of this ilk may well have stopped other voters from flipping from no to yes.

Curt Schilling (58.6% on 2022 ballot)

| Pitcher | Career WAR | Peak WAR Adj | S-JAWS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curt Schilling | 79.5 | 47.5 | 63.5 |

| Avg. HOF SP | 73.3 | 40.7 | 56.8 |

| W-L | SO | ERA | ERA+ |

| 216-146 | 3,116 | 3.46 | 127 |

From the intro:

On the field, Curt Schilling was at his best when the spotlight shone the brightest. A top starter on four pennant winners and three World Series champions, he has a strong claim as the best postseason pitcher of his generation. Founded on pinpoint command of his mid-90s fastball and a devastating splitter, his regular season dominance enhances his case for Cooperstown. He’s one of just 19 pitchers to strike out more than 3,000 hitters, and is the owner of the highest strikeout-to-walk ratio in modern major league history.

That said, Schilling never won a Cy Young award and finished with “only” 216 regular-season wins. While only one starter with fewer than 300 wins was elected [by the writers] during the 1992-2014 span (Bert Blyleven), four have been tabbed since then, two in 2015 (Pedro Martinez and John Smoltz) and two in ’19 (Roy Halladay and Mike Mussina), suggesting that’s far less of an obstacle than before.

Schilling was something of a late bloomer who didn’t click until his age-25 season, after he had been traded three times. He spent much of his peak pitching in the shadows of even more famous (and popular) teammates, which may have helped to explain his outspokenness. Former Phillies manager Jim Fregosi nicknamed him “Red Light Curt” for his desire to be at the center of attention when the cameras were rolling, while Phillies general manager Ed Wade said, “Schilling is a horse every fifth day and a horse’s ass the other four.” Whether expounding about politics, performance-enhancing drugs, the QuesTec pitch-tracking system, or a cornerstone of his legend, Schilling wasn’t shy about telling the world what he thought.

That desire eventually extended beyond the mound. Schilling used his platform to raise money for research into amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease) and, after a bout of oral cancer, recorded public service announcements on the dangers of smokeless tobacco. In 1996, USA Today named him “Baseball’s Most Caring Athlete.” But in the years since his retirement, and particularly over the past half-decade, his actions and inflammatory rhetoric on social media have turned him from merely a controversial and polarizing figure to one who has continued to create problems for himself.

More here.

For all of the ups and downs that preceded it, Schilling received 70% of the vote on the 2020 ballot, but he continued to add to the noxious cloud that has befouled his candidacy, stalling his progress. By the time I published the linked iteration of his profile on December 28, 2020, the stack of receipts for his behavior had grown to include sharing presidential election-related conspiracy theories; calling for a declaration of martial law; and comparing Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, to a Nazi.

After the December 31 voting deadline, Schilling doubled down by tweeting his support of the insurrectionists who stormed the U.S. Capitol building on January 6, a move that was a bridge too far for some voters who had otherwise continued to support him. Reportedly, at least one (and perhaps multiple ones) contacted the Hall of Fame about the possibility of rescinding their votes for him. According to Hall of Fame Ballot Tracker team member Anthony Calamis, by the end of January 2021, 22 voters had publicly indicated that they would either withdraw their support from Schilling on the 2022 ballot, or at least consider doing so.

When the dust settled and the 2021 ballots were counted, Schilling gained just 1.1%, and the BBWAA voters elected no one for the second time during his run. Realizing that his electoral goose was cooked, Schilling took the unprecedented step of requesting to be removed from the ballot so as to avoid any accountability for his actions, and he called the voters “a group of morally bankrupt frauds” to boot. The BBWAA responded by calling Schilling’s request a violation of the election rules, and the Hall’s board of directors concurred. Ultimately, he dipped by 12.5%, the 12th-largest drop of any candidate in the modern era, and became the first candidate ever to fall short in back-to-back cycles after topping 70%.

As a voter, I included Bonds and Clemens on my 2021 and ’22 ballots, because I continued a pre-existing principle from my days of virtual ballot exercises, drawing a distinction between PED infractions that took place during the game’s “Wild West Era” before testing and penalties were in place and those that came afterwards. While I had included Schilling in six out of eight virtual ballots, I left him off my actual ones, not because I put any stock in the character clause — I have not excluded any candidates on the basis of domestic violence allegations (such as the aforementioned ones against Bonds as well as Sosa, whom I voted for in 2021 but not ’22) or sexual improprieties (Clemens) — but because I had no interest in giving the man a more prestigious platform from which to share his unhinged and increasingly dangerous views. If I were on the Contemporary committee, I would take the same approach; Bonds and Clemens would be the only two of the eight to get my vote. I’ve already explored the other five candidates’ cases and found them wanting, for reasons detailed in the pieces linked in the navigation bar atop this one.

I don’t have a ballot this time around, however, and all of these candidates are somebody else’s problem. Because the Hall’s board of directors appoints the Era Committees — which generally consist of eight Hall of Famers, four executives, and four media members — I suspect that they have a reasonable idea of who their allies are when it comes to keeping PED-linked candidates on the outside, particularly from among the media, where the vast majority of voters choose to publish their ballots. While I don’t think that means we’ll see the Gruesome Twosome shut out entirely or even slip into the “fewer than X votes” group, it doesn’t take nearly that much to prevent them from getting to 75%. Thus, I don’t expect either to be elected anytime soon.

I’m less certain what to expect from the voters regarding Schilling. Much of his ire was targeted directly at the media, baseball and otherwise, and yet he was still nearly elected. I suspect that the executives and Hall of Famers, being far less online, are less aware of just how corrosive his public persona is, and I wouldn’t be surprised if he’s elected. I also wouldn’t be surprised if he falls short. If he is the only candidate elected by the committee, and the BBWAA doesn’t elect Scott Rolen or anybody else — a distinct possibility — summer in Cooperstown might not be so appealing.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

Please just make them go away. I don’t want to think about them anymore.

Ironically if voters just voted them in year 1, people would get upset for 2 weeks and we’d never ever hear about it ever again. Instead they dragged this out for 10+ years and make people remember the PED scandal over and over and get pissed at baseball writers over and over regardless of one’s opinion on the matter.

the harder you try to not think about things, the bigger they grow and the more omnipresent they seem to become.