Will MLB Turn to Expansion After Losing Revenues to COVID-19?

Over the last several decades, revenues for Major League Baseball have soared, nearing $11 billion last season. The league’s unprecedented prosperity has turned MLB franchises into cash cows in ways not seen in prior generations. It will likely take some time to gauge the extent of the revenue teams will lose due to COVID-19-related delays, but given that some or perhaps all of the 2020 season will be lost, baseball isn’t likely to be a great moneymaker for owners this year. And while league expansion has been talked about for quite some time, it’s possible the losses suffered this season due might actually be the precipitating factor in MLB moving beyond 30 teams.

For the last few decades, owners haven’t felt compelled to expand because they were making plenty of money without the need for a cash grab. The dirty truth about expansion is that it isn’t about growing the sport. It’s about injecting cash into ownership pockets now, with those same owners willing to share a slice of their pie with a couple more teams in the future. If the owners don’t feel the need for that expansion money, they aren’t going to welcome more teams to take a share of overall MLB revenues. In addition, the threat of relocation from teams looking for new stadium deals serves to slow expansion; MLB likes to have potential expansion cities available to threaten municipalities into providing new ballparks.

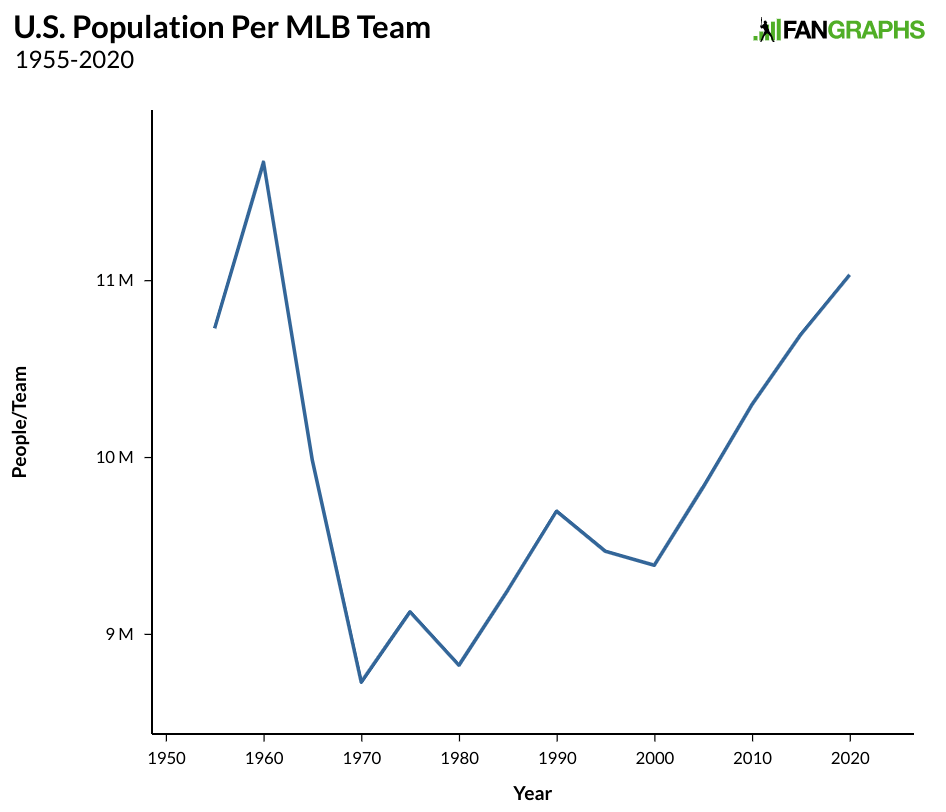

Modern expansion isn’t about the talent levels available or growing to meet the needs of an increasing population. If it were, we would have seen expansion at some point in the last decade. The talent pool has gotten incredibly good, with fastball velocities and strikeout levels rising to the point that diluting the talent pool could have a positive impact on the game, resulting in more action and balls in play. And in terms of population, the number of people per team is approaching levels last seen in 1960 when baseball had just 16 teams. The graph below shows the U.S. population and the number of major league teams in five-year intervals, to show how the number of people per team in the U.S. has changed since 1960: