The bullpen can be a weird place. While lineups and rotations across the big leagues have some degree of stability (albeit one threatened by recent spikes in injury rates), the amount of roster turnover in bullpens varies greatly. It’s a place where former failed starters and pitchers trying to get one last chance at the big leagues often find a home. Tyler Matzek and Daniel Bard were the latest reclamation projects turned into high-leverage relief pitchers when they returned to form last season. For Bard, it had been a full seven seasons since his last appearances in a big league game (2013 with the Red Sox). His performance earned him 2020 Comeback Player of the Year honors in the National League and a $2.9 million one-year deal to return in 2021 as the Rockies’ closer.

Is this unusual? Bard’s story certainly is, but it’s pretty typical for teams to pan for gold via non-roster invitees to spring training. Spring training rosters are limited to 75 players; teams will almost always fill this with the entirety of their 40-man roster supplemented by minor league players close to big league action and a handful of NRIs competing for a spot on the roster. Most NRIs don’t pan out and are either released or end up in the minor leagues, but occasionally they suit up for Opening Day.

Rex Brothers falls into this category. Now in his third attempt to recapture his form as the Rockies’ setup man and closer from 2011-15, Brothers looks like he’s figured some things out with the Cubs. Heading into yesterday, he’d made 28 appearances for a total of 24.1 innings (all stats are as of June 23). Those figures are the highest totals for Brothers since the 2014 season. In those innings he’s struck out 40 batters, leading to a career-best 38.5 K% and K-BB% of 25%. That K-BB% is good for 31st out of 200 relievers with at least 20 innings pitched. So far it certainly reads like a success story for the Cubs.

Brothers is no spring chicken (2021 is his age-33 season) but he has logged relatively few innings (293.2 total at the major league level and only 51.1 over the last five seasons), which may inspire some optimism that he has more left in the tank than his age would suggest. But the question remains as to whether he has staying power in the Cubs’ bullpen. I made mention of Bard and Matzek earlier. Matzek reappeared last season as a reliever for the Braves after a brief stint as a starting pitcher for the Rockies (the team that drafted him) back in 2014-15. His performance has regressed from his resurgent 2020, but Matzek has managed to keep his successful run going with an ERA of 3.33 and a FIP of 2.98 in ‘21. Bard has similarly maintained form. Matzek and Bard represent the high point for these kinds of reclamation projects. While unlikely, it’s far from unprecedented.

But let’s get back to Brothers. A reliever his whole career, he has relied primarily on a two-pitch mix of a four-seam fastball and a slider. His best pitch is his four-seamer, which he uses about two-thirds of the time; it tops out around 97. According to Sahadev Sharma of The Athletic, Brothers played through shoulder pain in Colorado, which he admits was a mistake. The shoulder ailment eventually led to surgery following his 2016 release from the Cubs, who had acquired him from the Rockies in ‘15. His road back to the majors has taken time. As is the case for many pitchers who go through injuries, his mechanics took a turn for the worse as his body compensated for the weak throwing shoulder. His first crack at a comeback was granted by the Atlanta Braves where he bounced back and forth between the majors and the Braves’ Double- and Triple-A affiliates. Never a strength for Brothers, his lack of control was at the heart of his struggles to get back to baseball’s highest level. He put it together briefly in 2017 when he pitched 23.2 innings for a 3.66 FIP but an awful 7.23 ERA. In 2018, however, Brothers walked 44 batters in 40.2 innings, including a whopping 17 wild pitches during that span. He faced a mere two batters at the major league level and walked both of them.

Another opportunity in 2019 with the Yankees followed by time with the Cubs in ‘20 yielded similar results: Brothers could not throw strikes consistently enough. He credits time working on his mechanics at the alternate site last season for his improved control. Look at the following GIFs. The first one is from 2020 and the second from ‘21. Notice how last season he was reaching his throwing arm down below his waist; this season his arm action is much shorter and more compact in comparison.

In his interview with The Athletic, Brothers expressed the impact his arm action also had on his lower half, stating, “My knee started caving towards home plate, which was forcing me down the mound way too soon. It was an inconsistent release point, and I was just feeling bad.”

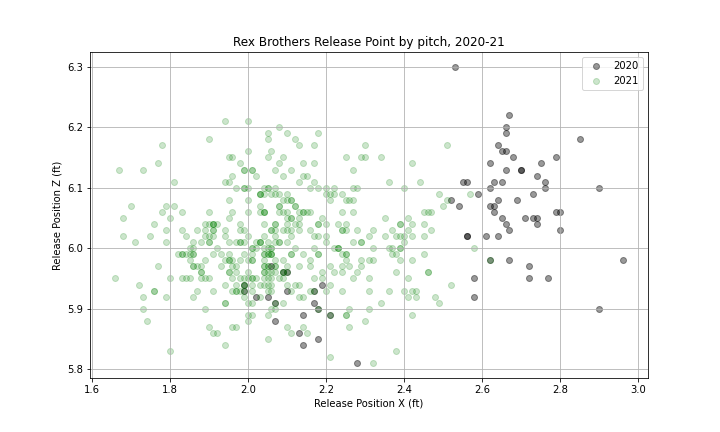

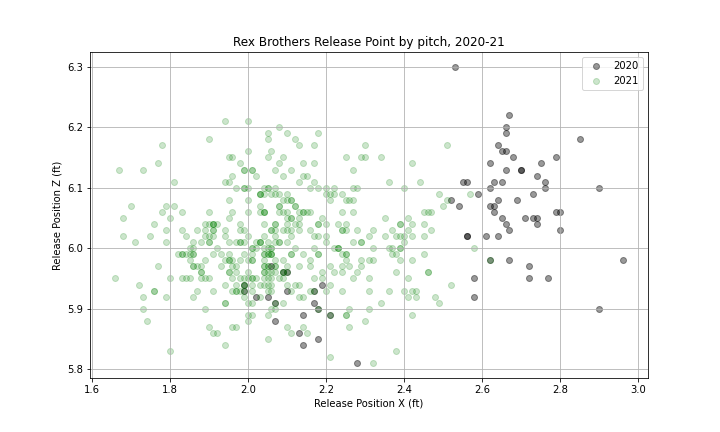

Statcast captures pitcher release points with every pitch. Looking at Brothers’ pitch data from the last two seasons, there’s evidence that the improvements in his delivery have helped him find consistency in his release point. The chart below shows pitch release locations for the 2020 and ‘21 seasons.

The release point distribution is quite different for the two seasons. The standard deviation for release point of his pitches in 2020 was 0.266 feet in the X direction and 0.103 feet in the Z direction; in ‘21, the standard deviation decreased significantly to .186 and .076. This holds true for both fastballs and sliders. He’s thrown over five times as many pitches this season, but even taking a random sample of data of the same size (74 pitches) as his data from 2020 the improvement in consistency is still evident.

Let’s be clear, Brothers still carries a BB/9 rate in excess of 5.00, but his propensity for strikeouts makes that number more palatable. Improving his release point seems to have allowed him to regain enough control to effectively leverage his strikeout ability. Brothers has thrown 36.6% of his pitches in the strike zone this season, tied for 12th lowest among relievers with at least 20 innings pitched. During his most effective seasons in Colorado (2011-13), he threw 44.9% of his pitches in the strike zone. He’s also allowing way more fly balls now (46.8% this season) than his days in Colorado (average of 32.6% from 2011-13), which has been detrimental to his home run rate (1.11 HR/9 allowed this season) although he’s right around league average. This season’s version of Brothers is a tad less effective than his younger self, but his 3.57 FIP makes him an above average reliever and a reliable left-handed option for the Cubs.

The Cubs have the fourth best bullpen in the majors by WAR at 3.2. Outside of Craig Kimbrel, who is also having a resurgent season, their relievers are not hyped prospects or big name free agent signings. It seems that the front office and coaching staff have found the ability to make the most of the pieces they have. Working with Brothers to rekindle some of the success he had early in his career is just an example of how many of the Cubs’ relievers are churning out career-best performances.