The Baserunning Madness of World Series Game 3

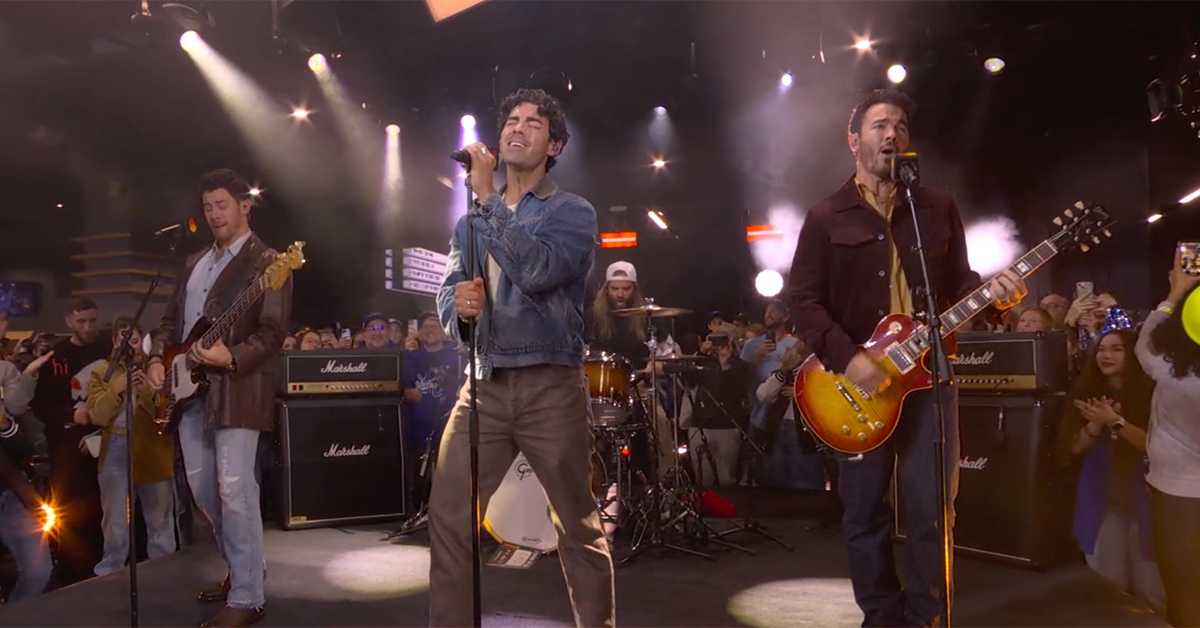

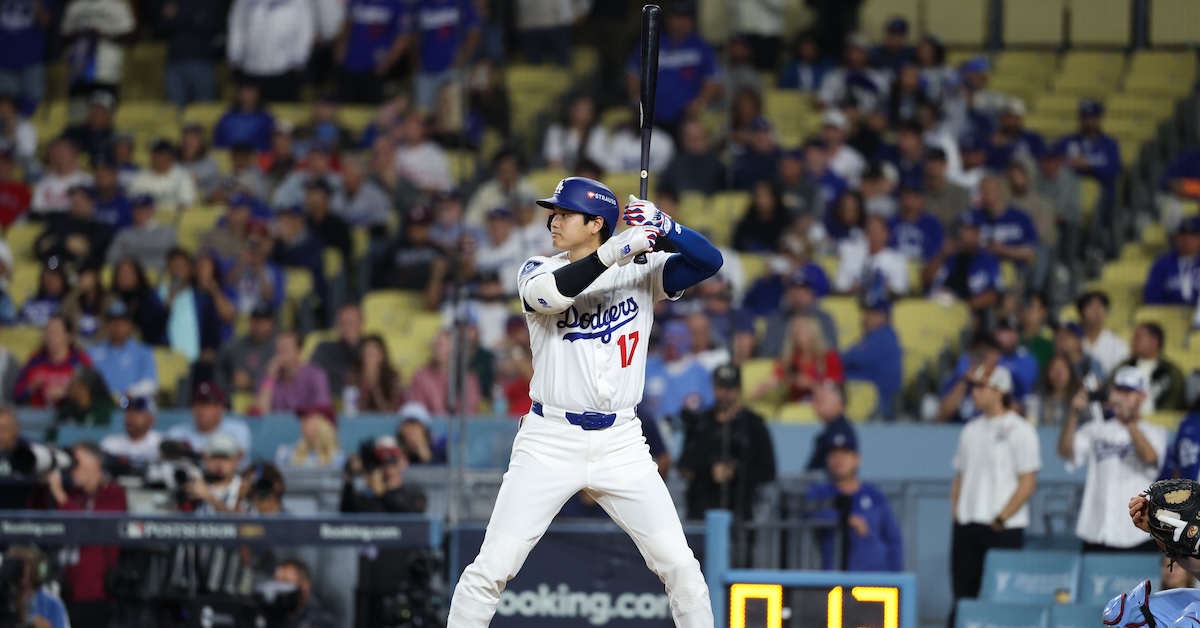

I honestly have no idea how many tag plays take place over the course of the average baseball game, but whatever that number may be, it felt like Game 3 of the World Series quadrupled it at the very least. We saw seven players thrown out on the bases. We saw challenges on plays at all four bases. We saw baserunning blunders, huge throws, and perfect relays. We saw aggressive sends that turned out well, and aggressive sends that led to players being thrown out at the plate by laughable margins. We saw pop-up slides that flew too close to the sun. We got a tutorial on the home plate blocking rule. We saw maybe the first ever umpire-induced pickoff. We saw the next day’s starting pitcher pull up with a leg cramp while running the bases in the bottom of the 11th inning. We saw multiple players get tagged out by a glove that caught them squarely in the Jonas Brothers. We saw the game’s 469th-fastest runner come in as a pinch-runner for the 606th-fastest runner. I could keep going.

At this point, I should mention that the litany you just read may or may not be my fault. Somewhere around the seventh inning, Meg Rowley asked me whether I might like to write about anything I’d seen during the game. I said there had been a couple interesting tag plays, so maybe it would be fun to write about them. Go back and reread the first sentence of this article. That’s when I wrote it, in the seventh inning, before like a dozen other absurd baserunning plays happened. This is how the baseball gods punish hubris, and there’s no way to delve into all these plays in one article. Even if there were, I wouldn’t be in any shape to write it, because I watched the entire 18-inning game and got like four hours of sleep last night (read: this morning). Instead, we’ll be taking a jogging tour of the tag play highlights, pointing out a few fun facts and then skating on to the next destination. Read the rest of this entry »