With the calendar turning to late May, it feels strange to say that the industry is still a long way from making 2021 draft selections, but the new July start date isn’t the only unique thing about this year’s draft. The ongoing global pandemic and the larger player pool created by last year’s draft being reduced by nearly 90% have created additional challenges in terms of preparation for July 11. With just under two months to go before teams are on the clock, I got it touch with a number of key decision makers around baseball to get a better sense of what’s going on behind the scenes.

Dealing With the Information Deficit

The pandemic has created a variety of evaluation challenges, but few have had a greater impact than the lack of a 2020 Cape Cod League and the highly abbreviated and lightly attended high school summer showcase season. These lost opportunities to see potential draftees play against the best of their peers have left teams without one of their loudest data points as they begin to print out magnets and line up their boards. “With college hitters, we’re no more certain than we are with the high school guys right now,” said one National League scouting executive. “We just don’t have the big data advantage for college players that we used to.” One American League executive agreed, but not to the same extent. “We are poised for more uncertainly and variability due to the smaller track records, but it’s not as uncertain as I expected it to be.”

Another AL decision maker said that last year’s limitations in terms of scouting have provided an unexpected benefit in terms of dealing with this year’s challenges. “We learned in last year’s draft that there is still a lot of information out there and ways to evaluate it that we hadn’t taken advantage of in the past,” he said. “We were forced in 2020 to be open to different ways and now it’s become a new way of doing things.”

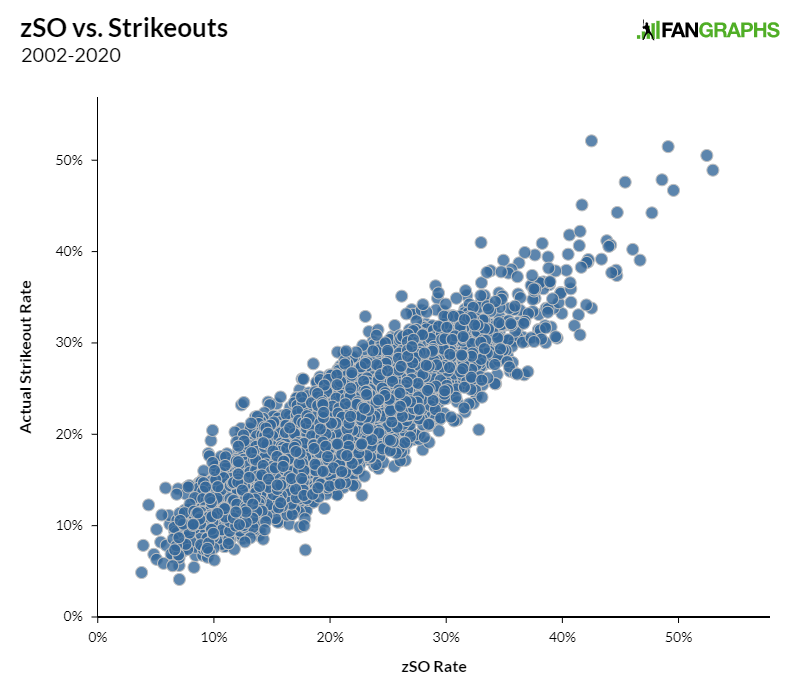

One of the most impactful innovations over the last decade has been that of the draft model. Nearly every team utilizes some kind of projection and/or scoring model that takes in historical performance and other, more advanced data sources and spits out some measure of draft value, but one American League evaluator worried that the lack of recent information will result in a garbage in/garbage out scenario. “We have guys who had a rough three weeks in 2020 but are playing well now,” he said, lamenting the incredibly small samples produced by the pandemic. “I think a lot of models are just going to have to be thrown out the window this year.”

More Players, More Problems

There were 1,217 players selected in the 2019 draft. In 2020, the number was reduced to 160. That leaves over 1,000 potential draftees who returned to school, transferred to new schools or entered the college ranks with the plan of impressing scouts for next year. That sudden glut of players was expected to complicate matters greatly, but late into the 2021 scouting season, teams have found the suddenly larger player pool isn’t impacting their processes as much as they initially anticipated. “There’s a handful of guys who had to come back that are going go in the first two days,” said one National League exec. “But I don’t think it’s that many of them; we’re certainly not going to see some flood of 22-year-olds,” he concluded, noting that age plays a massive role, as teams are weighing date of birth more heavily than ever. “Once you’re 22, the bloom is off the rose,” another executive added. One American League executive agreed that the large player pool will have little effect early, but should begin to play into later selections. “It doesn’t feel like twice the number of players, for whatever reason,” he concluded. “I do think that it’s going to become a factor from rounds six through 20, and I think that teams are still figuring out how to draft when it’s down to 20 rounds.”

Early Disappointment in the New Draft League And Combine

Another twist to this year’s draft has been the establishment of the new MLB-organized Draft League, which was cobbled together from six Northeast teams that lost their minor league affiliation, as well as a medical and performance combine in late June. These were generally seen as positive developments when initially announced, but the list of players participating has left much to be desired for teams looking for more information.

Some are taking more of a wait-and-see approach to an event that is just getting going and is dealing with the same real-world challenges everyone has been grappling with over the last year and a half. “I would expect it to take some time with people easing into it,” said one American League executive. “Let’s get past the pandemic before we start judging.” Another AL decision-maker agreed. “I think the intention is good and it’s going to take some time to make it normal for people,” he explained. “It’s all new and it’s going to take some time. It’s not a bust as much as it’s a work in progress.”

Still, some are disappointed by the early returns. “There are names going into that Draft League and they aren’t even Day Three options,” said one exacerbated National League executive. “You’ve got guys that are barely playing for their college team this spring but they are going to play there. Going would be a waste of time for us.”

“I’ve just kind of blocked it out,” said a senior American League scout. “I’m just going to the Cape.”

Multiple insiders brought up the CBA in terms of the combine, saying that how everything unfolds in this year’s negotiations will help define the future efficacy of the event. Others argue that as with other sports, many top prospects will continue to avoid something that can only create negative value for them. “If you are an agent with a brain, why would you send your player there?” Asked one National League executive. “All you can do is lose money.”